Executive Summary

Growing concerns have been expressed in media commentary and policy circles about the economic fortunes of young Australians, especially Millennials and Gen Z’ers. One of the key indicators in assessing the long-term economic wellbeing of younger generations is intergenerational income mobility — the extent to which young people’s incomes earned over time exceed that of their parents.

Intergenerational income mobility can broadly be measured in relative terms (tracking movements of young people within the income distribution compared to their parents) or in absolute terms (tracking extent of income growth for young people over time as compared to their parents).

A number of empirical studies have been produced to quantify the degree of intergenerational mobility in Australia. While the correlation between parental and offspring income varies across available studies, a common finding is that the extent of Australian intergenerational income mobility is less than that in certain continental European countries and Canada, but exceeds that found in the United States and United Kingdom.

Economic studies indicate there exists a ‘Great Gatsby’ curve, showing a negative association between income inequality and intergenerational income mobility. The existence of the Great Gatsby curve has been taken by some academics and policymakers to imply a causal relationship between inequality and mobility that justifies larger ‘tax-and-spend’ redistributive programs to bolster mobility for young people.

However, recent contributions to the income mobility literature question the causal link between inequality and mobility, pointing to the role of institutions and policies in affecting rates of upward income mobility over time. Empirical investigations support the suggestion that poor quality economic institutions inhibit mobility outcomes.

Fiscal, legal, and regulatory settings that do not respect private property rights, and that restrict gains from entrepreneurship, education and training, and productive economic activity, are identified as barriers to upward mobility, including for young people. This paper argues that institutions that facilitate the availability of greater, and meaningful, economic choice would empower young Australians in discovering their own, preferred pathways for upward mobility and material prosperity.

Introduction

Anecdotal concerns over the present socio-economic circumstances of young Australians, and their future prospects, abound. There is general agreement that interwoven developments such as recessions and joblessness, indebtedness, pandemic restrictions, rising inflation and cost of living pressures are affecting people in younger age cohorts both disproportionately and adversely. To be certain, uneasiness over economic and social trends as they affect young people is nothing new — for instance, expressed concerns over rising residential property prices, and a concomitant lack of housing affordability, have long served as a lightning rod for conversations about intergenerational fairness and equity.1

Deeply-seated psychological aspirations for continuous improvement in the livelihoods of our next generations undoubtedly animate contemporary discussions, though it might be argued that conditions facing our young people have assumed even greater focus against the background of recent domestic and global crises and tensions.

Perceptions that Australia’s youth face an array of challenges, which are likely to persist in the years ahead, has been reinforced by a range of qualitative evidence. In particular, survey evidence collected during the Covid-19 pandemic highlighted anxieties and other mental health problems faced by young people, as their schooling and social interactions were being disrupted.2

The suggestion that life is getting harder for young people, and will remain so as they mature into adulthood, is seen to translate into cultural and social perceptions viewed as undermining the basis of future prosperity. Sensed hardships are deemed to exacerbate alienation and frustration with existing economic, political, and social arrangements, to the effect that conventional systems are ‘not working’ to advance the interests of young people.

Feelings of being ‘stuck’ — economically and socially — appear to be fueling some young people’s tendency toward socialistic ideas.3 Consistent with all these varied concerns, intergenerational inequality has been referred to in academic, policy, and media circles as a significant issue potentially confronting younger generations in coming years.4

Evidence points to improvements in both the material and non-material circumstances of successive generations of Australians in certain key indicators — for example, infant and child mortality, and educational attainment.5 The ‘scoreboard’ displays a clear trend of improvement over a range of (but not all) key statistical indicators spanning decades. Concerns over the recent progress of young people should also be qualified by an understanding that, as they increasingly attain educational qualifications and gain skills, they are deferring having families and buying houses.6 Furthermore, there are suggestions that prospective asset inheritances, especially in respect of housing, in coming years will ease future economic and social pressures on young people, as they begin their careers and start families.7 Nevertheless, widespread commentary about limited opportunities and the curtailment of aspirations gives reasonable grounds to carefully consider how to better secure the future for young people — our ‘Generation Next’ of leaders in business, politics, and in other pursuits, as well as the future of Australian families and communities.

The aim of this paper is to consider the basis on which young Australians would be able to register improved living circumstances over their lifetimes. The paper pursues this aim through the prism of studying trends of, and factors impinging upon, intergenerational income mobility.

Intergenerational income mobility is defined as the extent to which the incomes of individuals differ from those obtained by their parents.8 Throughout this paper, the term ‘intergenerational income mobility’ is used interchangeably with the terms ‘income mobility’ or ‘mobility’, unless otherwise indicated. Within this umbrella concept, mobility can be measured either:

- in relative terms, which compares the movement of young people within the income distribution with that experienced by their parents; or

- in absolute terms, which compares the extent of income growth for young people over time as compared to their parents.

Although income is not the sole, or all-encompassing, dimension of human welfare, the importance of income mobility across the generations cannot be overstated. It is assumed here that greater income provides individuals with the capacity to possess greater command over those resources that underpin improvements in living standards.

This paper argues that many (though not all) of the seemingly disparate themes concerning the wellbeing of young Australians are connected by an underlying theme: will young Australians get to enjoy better living standards than those enjoyed by previous generations? To better understand the basis for securing greater prosperity and wellbeing for younger generations, the significance of intergenerational income mobility is sketched out.

As will be outlined, studies have shown high rates of income mobility equip individuals with greater purchasing power, and enable them to better prepare for future plans and contingencies. Mobility is also connected with improvements in self-perceived life satisfaction and wellbeing. Evidence suggests greater mobility will help unlock the aspirational impulses of young people, allowing them to move ahead in life as they see fit.

In addition to outlining the theory and empirics of mobility, this paper will outline the significance and impact of better policies and institutions. A range of conceptual perspectives — including the economics of entrepreneurship, the political economy of institutions, and the sociology of aspiration — will underpin the argument that policies and norms that promote aspiration, meaning, and a personal sense of self-determination are vital prerequisites to ensuring young Australians grow and live in an environment of robust opportunities for wellbeing. Studying institutional quality’s various effects on socio-economic conditions overcomes the limitations presented by literature that merely focuses upon monocausal determinants of problems facing youth (such as inequality). The key here is to examine the basis upon which young Australians can discover their own pathways for leading better lives.

The structure of this research report is as follows. The next section presents an overview of conceptual and empirical research into the nature and implications of income mobility, and how mobility affects young people. This is followed by a discussion about the institutional factors influencing the escalation of young people up the income ladder, including the presentation of a conceptual framework linking economic freedom, mobility, and better opportunities for future generations.

Using this framework, the paper then advances a range of key reform pathways to better enhance aspiration and upward mobility for young people — centering on better services provision, motivating youth entrepreneurship, and removing immobility traps caused by restrictive regulations and fiscal policies. The conclusion provides a summary of the key arguments.

Intergenerational income mobility: Concepts and empirical evidence

One of the distinctive features of economic policy discourse over the past 20 years has been the focus upon distributional issues. Concerns have been raised about the degree of income inequality within countries and, in particular, estimates revealing widening gaps between rich and poor (or the so-called ‘top one per cent’ versus the remaining ‘99 per cent’) have sparked calls for assertive tax-and-spend redistributive policies.9

Although empirical estimates of worsening inequality, and the economic consequences of redistribution, have been challenged,10 this paper draws attention to yet another reason the inequality concerns should be qualified, at least to some extent. The largely static accounts of the distribution of income have overlooked that individuals and relevant groups, such as households, do not remain static within the distribution. People tend to move up, or down, within the income distribution — in other words, there is mobility.

There is now an abundant literature focusing upon income mobility questions, with some of the most prominent academic figures in economics and social science disciplines focusing upon these particular matters.11 Generally speaking, income mobility may be considered as the extent to which an individual, or a group such as a household, experience changes to their income levels over time. The reality is that this general definition obscures the multifaceted and complicated nature of mobility, and the variety of questions the concept raises — both conceptually and empirically.

The emphasis on income mobility in this paper, which is centered upon intertemporal changes in the flow of cash (in the form of salaries and wages, interest income, etc.), is distinguished from analysis of wealth mobility in terms of changes in the valuation of assets over time. There are clear links between income and wealth, and the extent to which individuals and groups experience mobility with respect to these variables. Wealth mobility is important in the Australian context, given the significance of housing and superannuation funds as asset classes. Unless otherwise indicated, this paper focuses upon income mobility considerations as they affect young Australians.

Mobility investigations are also distinguished by their focus on either intragenerational or intergenerational mobility. Intragenerational mobility is concerned with understanding how the income of a given individual or household has changed over the course of time, especially as they progress from childhood and adolescence into working-age adulthood, and then into retirement.

Intergenerational mobility refers to how income changes in comparison with previous generations — for example, how the income of a young adult compares with that of their parent/s, when they were the same age. As already indicated, the primary focus of this paper is upon intergenerational mobility.

Another factor to consider is whether mobility is being understood in absolute or relative terms. Given the focus in recent years on inequality outcomes, it is unsurprising that much attention is directed toward relative mobility trends. Relative mobility focuses upon the movement of individuals, or households, across the income distribution over time in comparison with others.

From an intergenerational perspective, a person is relatively better off if they find themselves, at any given time, positioned higher within the income distribution than their parent/s. Absolute mobility is an alternative measure that, by ignoring relative rankings between people or groups, provides an indication as to whether incomes have risen or fallen (in nominal or real terms) over time. If the income of a person at a given time exceeds that of their parent/s, they have experienced upward absolute mobility. This paper will discuss studies that refer to estimates of both relative and absolute mobility.

Drawing attention to mobility highlights the realities of change that are discounted — or even ignored — by static accounts of socio-economic phenomena. Specifically, “[a]ny quintile of the distribution is not composed of exactly the same households year after year. Instead, households shuffle and sort as they age, marry, move up in the labour market, and encounter good and bad luck.

Paying attention to mobility, as well as inequality, gives us a richer picture of the income possibilities for households over time.”12 Fundamentally, income mobility is also associated with situations wherein successive generations of individuals, or their families, concretely experience economic betterment — in the form of greater income through gainful employment, as well as through greater purchasing power and the ability to amass additional products and resources.

While there remains debate within academic literature as to the direction of the relationship between income mobility and life satisfaction, a number of international studies lend support to the idea that upward mobility is associated with positive outcomes in subjective wellbeing and other life satisfaction measures.13 The extent to which people are able to achieve a reasonable degree of upward income mobility also assumes political import; as attested by discussions as to whether empirically-estimated mobilities resonate with ingrained political beliefs about the existence of widely-accessible life opportunities.14

What does the empirical evidence suggest in terms of intergenerational income mobility in Australia? How does Australian mobility estimates compare against other countries? Growing scholarly attention has been paid to presenting mobility estimates in the Australian context, and the rest of this section will be dedicated to providing a summary of results that have been produced over the past 15 years or so. The studies outlined here provide estimates for what is known as ‘intergenerational income elasticity’.

The intergenerational income elasticity measures the extent to which the income of children is affected by the income of parents, or (to be more precise) the association between the percentage change in sons’ or daughters’ income with respect to a percentage change in fathers’ or mothers’ income. An elasticity value of zero implies that income across generations is highly mobile, and that differences in parental and offspring income do not intergenerationally persist. An elasticity value of one implies that differences in parental income are transmitted to children in full, and that there is complete immobility.15 In other words, a lower elasticity value indicates a higher degree of intergenerational mobility.

The first of the contemporary Australian cohort of intergenerational mobility empirical studies is that produced by academic economist-cum-politician Andrew Leigh. In a 2007 paper, Leigh assessed the relative mobility of occupational earnings for fathers and sons in Australia. Drawing upon a range of surveys containing earnings data from the 1960s to the early 2000s, and using sons’ reports of their fathers’ occupations to predict fathers’ earnings, Leigh estimates a father-son earnings elasticity figure.

For the most recent survey, the figure is about 0.2, implying that a 10% increase in a given father’s earnings increases his son’s wage by two%.16 Using survey data to compare the degree of intergenerational mobility in the 2000s with the level of the 1960s, Leigh finds that “the level of intergenerational earnings mobility in Australia today is similar to the level prevailing in the 1960s.”17 Leigh uses the same methodology to empirically estimate the earnings elasticity for U.S. fathers and sons, with the estimated figure of about 0.3 implying that Australian males enjoy relatively higher rates of intergenerational mobility than their American counterparts.

Silvia Mendolia and Peter Siminski follow the methodology adopted in Leigh’s study but draw upon a greater sample of longitudinal data, including 12 iterations (or ‘waves’) of the Melbourne Institute’s Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey.18 The father-son earnings elasticity figure computed by Mendolia and Siminski is 0.35 (implying that a 10% increase in a father’s earnings is associated with a 3.5% increase in a son’s earnings), which is about a third larger than that estimated by Leigh. When combining their result with international estimates previously provided by Miles Corak,19 the authors conclude that: “Australia is not particularly mobile in an international context. It is less mobile than the Scandinavian countries, as well as Germany, Canada and New Zealand, but is more mobile than the USA and the UK.”20

A 2016 study by Yangtao Huang, Francisco Perales, and Mark Western also provides an elasticity estimate for intergenerational mobility using earnings data of Australian fathers and sons.21 This study uses 13 waves of the HILDA longitudinal survey between 2001 and 2013.

Using a two-stage regression model method for calculating the earnings mobility elasticity, and making requisite methodological adjustments accounting for issues such as occupational and earnings data quality, the authors presented a preferred elasticity range of between 0.24 and 0.28, which is comparable to Leigh’s earlier study.

A 2018 study published in the journal Economic Record presented Australian estimates of intergenerational mobility using direct income observations over two generations of parents and children (male and female).22 Using 15 waves of the HILDA survey, Murray, Clark, Mendolia, and Siminski are able to examine the household parental income (as opposed to earnings, as with previous studies) with the offspring income of those born between 1984 and 1986, when they were aged 15–17 in 2001, and then when they were aged 30–32 in 2015.

The initial elasticity estimate is about 0.28, and after adjusting this estimate for short run variability in parental income data, is revised to about 0.41. Taking into account differences in estimation approach across countries, the authors suggest Australians have enjoyed intergenerational mobility at a greater rate than Americans.

Another Australian intergenerational mobility study by Fairbrother and Mahadevan also draws upon HILDA longitudinal data for 13 waves, covering earnings data over 2001–2013 for all combinations of mothers, fathers, sons, and daughters.23 The authors compute a father-son elasticity estimate of 0.202, a father-daughter figure of 0.081, a mother-son elasticity of 0.16, and a mother-daughter elasticity figure of 0.151.

Their elasticity estimates imply that “a 10% increase in fathers’ hourly wages is associated with a 2.02% increase in sons’ hourly wages and a 0.81% increase in daughters’ hourly wages … A 10% increase in mothers’ hourly wages is associated with an increase in the hourly wages of sons and daughters of 1.60%, and 1.51%, respectively.”24

Table 1 summarises the national-level intergenerational mobility elasticity estimates already referred to in this paper, with the studies broadly indicating that a 10% increase in a given father’s earnings (or income) is associated with a 2–3% increase in their son’s earnings (or income).

Table 1: Australian intergenerational mobility elasticity estimates

|

Study |

Elasticity estimate |

|

Leigh (2007) |

0.2 |

|

Mendolia and Siminski (2016) |

0.35 |

|

Huang et al. (2016) |

0.24-0.28 |

|

Fairbrother and Mahadevan (2016) |

0.202 |

|

Murray et al. (2018) |

0.409 |

Notes: Table reports father-son elasticity values. Lower elasticity values indicate greater degrees of intergenerational mobility. Reported results pertain either to directly measured and imputed income; refer to individual studies for additional information.

Sources: Various papers.

Australia maintains a federal system of public governance, with potentially significant interjurisdictional economic, social, and policy differentials that may influence intergenerational mobility outcomes across the states and territories. A study for the Victorian Department of Treasury and Finance used HILDA data from 2001–2016 to appraise the extent of father-son intergenerational earnings mobility in New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland.25 Adjusting for biases attributed to issues such as imputed fathers’ earnings and clustering in occupational statistics, the authors estimate earnings mobility elasticities for Victoria of 0.24, followed by Queensland (0.38) and NSW (0.49). This suggests the Victorian population is intergenerationally more mobile than the other two states in the data sample.

Nathan Deutscher and Bhashkar Mazumder produced interjurisdictional estimates for 87 Australian regions (Statistical Area Level 4, as classified by the Australian Bureau of Statistics). A range of regions, such as parts of the metropolitan capital cities, had computed elasticities of 0.18 or lower. Notwithstanding the beneficial impacts on mining activities in promoting upward mobility in Queensland and Western Australia, and the more general effects of stronger labour markets and high rates of school attendance in weakening intergenerational income persistence in some regions relative to others, the authors generally find less variation in intergenerational income mobility between Australian, compared with U.S., regions.26

As they state, “a child born to parents at the 25th percentile in a mobile Australian region (at the 90th percentile of regions ranked by mobility) can expect to end up only 8 percentile rank points higher than if they were born in an immobile Australian region (at the 10th percentile of regions). For the United States, the gap in expected outcomes for a poor child between high and low mobility regions is nearly double this, at 15 percentile rank points.”27

The preceding discussion relates to relative measures of intergenerational mobility. A recent contribution to the literature by Kennedy and Siminski has provided a study of absolute intergenerational income mobility for Australia, covering 1950–2019.28 Using tax data and income surveys that provide direct observations of parental and offspring incomes, as opposed to imputing parental income data indirectly via occupational status, the authors compare the real incomes of 30–34-year-olds with their parents at the same age. For the majority of birth cohort studies, about two-thirds of children had higher incomes than their parents.

For the most recent birth cohort (those born in 1987), 68% of children had higher incomes than their parents (with the absolute mobility rate increasing even further, to 78%, when using household-adjusted, equivalised incomes). These figures exceed similar figures for the U.S., and compare with Scandinavian countries. Whilst the absolute mobility figures are stable from the 1962 birth cohort onwards, absolute mobility has fallen when using the 1950 birth cohort as the baseline (where 84% of those born in 1950 had higher income than their parents).

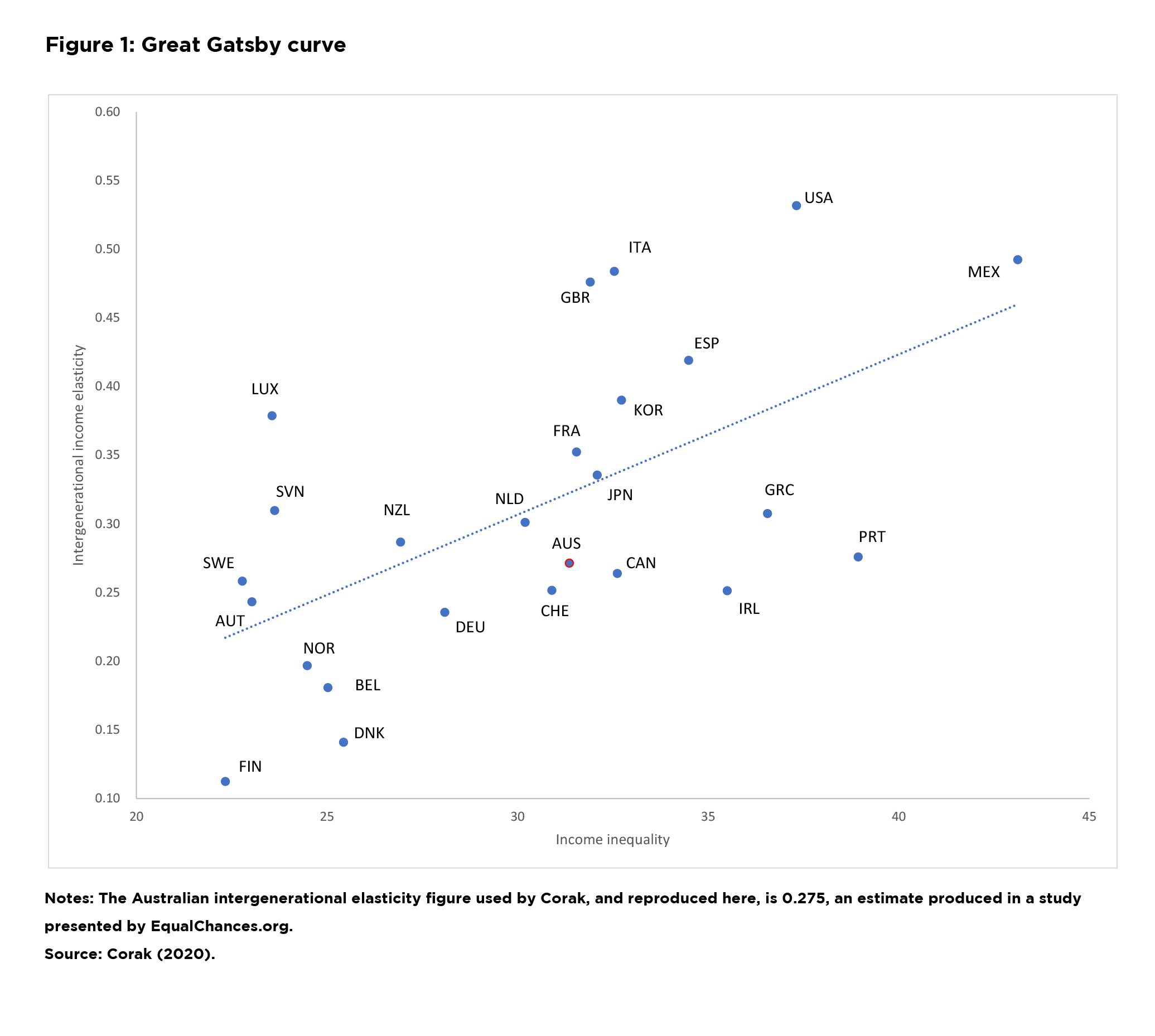

Considerable effort has been undertaken over the past decade or so to present internationally comparable evidence on mobility rates across countries. Much of this evidence has been totemically represented by the so-called ‘Great Gatsby’ curve, which illustrates a negative correlation between degrees of income inequality and intergenerational mobility. This curve was published in studies by Canadian economist Miles Corak, and thereafter popularised by Alan Krueger, chair of former U.S. President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers.29

Figure 1 illustrates the Great Gatsby curve, drawing from information presented in a 2020 Australian Economic Review article by Corak.30 On the x-axis is a measure for the ‘Gini coefficient’ degree of income inequality, with a higher number signifying a more unequal distributional outcome. On the y-axis is the father-son intergenerational income elasticity, with a higher number indicating greater income persistence (meaning a lesser degree of intergenerational income mobility).

The sample is for OECD member-countries for which there are available data. The data point for Australia is indicated by the red dot in the diagram. As Corak describes it, “[t]he Great Gatsby Curve shows Australia middling inequality and middling mobility.”31 Positionally, Australia stands in contrast to the relatively higher inequality-lower mobility mix of the U.S., and the relatively lower inequality-higher mobility mix of Scandinavian and certain European countries.

Popular commentary gives the impression that the Great Gatsby curve has been interpreted to effectively suggest a causal, rather than correlative, relation between inequality and mobility. Specifically, the claim is that inequality prevents young people from being able to exercise upward mobility over their lifetimes; transcending the incomes enjoyed by previous generations such as Baby Boomers and Generation X: “increased inequality has reduced the income in low-income families and that the lack of resources during upbringing has long-term negative consequences for children.”32 Eminent Chicago economist Frank Knight once surmised that long term earnings potential is influenced by a mix of inheritance, luck, and effort,33 but variables such as genetic endowments and parental ability to invest in the education of their own children suggest that not every young person possesses an exactly equal grasp of available material opportunities.34 If the resultant inequality causes immobility — as some analysts and commentators are prone to assert — then it is purported to follow that redistributive public policies are necessary to simultaneously reduce inequality and promote intergenerational mobility.

The suggestion that the Great Gatsby curve establishes a causal connection between inequality and mobility has been challenged in several ways. Most naturally, certain academics and commentators have made the oft-stated qualification that correlation does not imply causation. Corak himself stated that the curve does not denote a causative relation between income inequality and intergenerational income mobility.35 Thinking about the dynamic nature of inequality more broadly, higher rates of income inequality at any given point in time obviously do not imply intertemporal stasis within the income distributional ranks. This is illustrated, for example, by the turnover of ‘rich lists’ over time, as well as the panoply of ‘riches to rags’ studies of the corrosion of high-income status positions due to competition, technological change, financial ineptitude, and other factors.36 Indeed, studies of relative mobility, such as those covered in the previous section, illustrate the reality of intergenerational movements both up and down the income distribution. In addition to the nuanced, yet important, distinction between correlation and causation, some scholars have problematised the use of certain empirical measurements in the construction of the Great Gatsby curve as it was presented in earlier studies.37

Although estimates about the extent of intergenerational mobility vary, available evidence suggests Australia is mid-ranked among advanced countries on intergenerational income mobility outcomes. This implies the need for additional efforts to enhance the long-term capacities of young Australians to move up the income ladder, as well as redressing the deleterious effects of recent economic pressures that have disrupted the pathways for young Australians to secure quality education and work. There are also salient questions about the capacity of young people to cope with strong cost-of-living increases in recent times, and the ability to translate income into wealth (say, through house purchasing).

This leads to determining a reform posture that will best promote intergenerational mobility outcomes. The next section addresses this question from the perspective of two competing positions: the first being a redistributionist ‘tax-and-spend’ approach, and the second focusing upon the need for improved institutional quality (as proxied by economic freedom indicators).

Redistribution or institutions? Assessing two contrasting perspectives to enhance intergenerational income mobility

As has been shown, intergenerational mobility is a distinctive sub-strand of academic inquiry and policy discussion, with stand-alone issues regarding measurement of the degree of association between parental and offspring earnings incomes. Given the predominant focus on inequality matters more broadly over the past few years — especially since the 2007–2008 ‘global financial crisis’ — it is unsurprising that data on young people’s mobility has been assimilated into generic debates about income inequality. The potentially adverse effects of inequality on intergenerational mobility rates are starkly visualised by the Great Gatsby curve. And the curve has been used to argue for more redistributive government policies; using fiscal transfer programs (in particular, welfare payments to individuals and households) and progressive tax policies. A significant body of literature has also focused upon increasing education spending, and improving the quality of educational provision, in recognition of the long-term importance of schooling, vocational education, and skills training in promoting income mobility across generations.38

The broad policy stance that governmental fiscal redistribution will unlock intergenerational mobility requires rethinking, because excessive redistribution is likely to depress mobility rates. For example, public investment in education contributes to upward mobility — especially for those from low-income backgrounds, whose parents have insufficient means to invest in their children’s education — but the broader implications of redistributive fiscal transfers and other forms of government spending must still be accounted for. In particular, trade-offs need to be recognised between the benefits of spending in preventing the persistence of intergenerational immobility, and the disincentive effects of taxation to finance the spending.39

Heavy taxes are likely to further constrain a family’s ability to invest in their children, especially if those tax burdens are felt by families of more limited means. The burdens also pose as a barrier for people seeking to progress up the income ladder — including younger generations seeking to commence their careers — owing to ‘poverty traps’ posed by high effective marginal tax rates.40

Researchers in recent decades have devoted some attention toward the intergenerational transmission of welfare dependence and poverty among certain Australian households. Although the extent of intergenerational welfare dependency is contingent upon the design attributes of transfer payments (such as means testing, and other eligibility features) received by household members from government, there is some evidence to indicate the existence of entrenched disadvantage that transmits intergenerationally within households.41 Speaking more generally, people experiencing longer periods of income poverty and material deprivation appear less likely to exit such situations.42

The effects of dependency on government welfare programs across generations are not limited to economic and financial circumstances, but also take on sociological dimensions. For instance, there is the concern that parents in welfare-dependent households may be less likely to transmit work-ready ethics and norms to their children.43 The basic proposition is that redistribution, if not carefully calibrated — especially in conjunction with an additional array of disadvantage indicators — may diminish mobility.

The preceding discussion has focused upon issues surrounding the correspondence between inequality and intergenerational mobility, and the influence of public policies upon those features, given the state of institutions. However, the derivation of the Great Gatsby curve is informed by the association between inequality and mobility among a range of countries whose institutional environments are known to differ considerably. But institutions, themselves, are likely to shape intergenerational income mobility trajectories. Indeed, a generation of scholarship under the heading of ‘new institutional economics’ indicates that inter-country institutional differences are likely to — among other things — shape both intergenerational mobility patterns and income inequality outcomes. Furthermore, as historical and even more recent experiences attest, institutional configurations do not remain fixed and are, thus, subject to change.44 In short, the explicit consideration of institutions further complicates narratives to the effect that the Great Gatsby curve implies more redistribution alone will catalyse intergenerational income mobility.

It is worthwhile to explore the institutional dimensions of income mobility in greater detail. A range of formal institutions, such as political constitutions, legislation, policies, and regulatory and fiscal settings, are widely regarded as influencing the economic returns associated with productive activities — such as human capital investment (education and skills training) and entrepreneurship — which, in turn, would be broadly anticipated to promote upward mobility, including for young people.

Institutional settings that effectively and robustly safeguard the capacity of individuals to protect and uphold their property rights — including the ability to accumulate income without heavy and unjust fiscal-regulatory penalties — are regarded as providing a spur to improvements in mobility (including along intergenerational dimensions). By contrast, institutions that insufficiently respect the rights of people to justly pursue their own means of betterment are more likely to impose constraints on intergenerational income mobility. As Rehbinder and Liss remark, “the Great Gatsby relationship, in large part, could be explained by the fact that many countries with low mobility and high income inequality fail to provide basic libertarian rights, which both makes them economically immobile and unequal.”45

Institutional quality potentially affects the degree of mobility, when unproductive activities such as ‘rent seeking’ are manifest in any given society;46 wherein individuals and groups try to manipulate policy or economic conditions for their benefit, at the expense of others.47 In an institutional environment that facilitates — if not encourages — rent seeking, people may perversely strive for betterment by seeking politically-provisioned advantages, and the incomes of those who win rent-seeking ‘contests’ may be augmented as a result.

However, the broader societal losses attributed to rent seeking are likely to result from enacting regressive policies undermining the widespread — and pro-mobility — effects of market competition, and undermining the ability to acquire, use, and transfer wealth. As rent-seeking behaviour becomes more prevalent, entrepreneurial attentions become increasingly (and unproductively) diverted from profit seeking and the concomitant motivations to fulfil the needs of market consumers.48

A rent-seeking society also distorts the returns to human capital investment, and undermines equality of opportunity. The reward from rent seeking — as opposed to profit seeking — is likely to incentivise education and training efforts in directions not conducive to inclusive economic growth and widespread material prosperity. As indicated by Justin Callais:

“while skills obtained in a corrupt institutional environment might make the individual better off, this could be achieved in a societally unproductive manner. … in a country with little legal integrity and high level of corruption, investments in human capital: i) might not be distributed evenly throughout the society, leading to subpar outcomes for those at the bottom of the societal ladder, and ii) the skills learned would be more likely to be used in rent-seeking activities that benefit the politically connected.”49

Consistent with Callais’ first point, another study that incorporates institutional factors in the determination of intergenerational income mobility expresses the possibility that “in countries where rich dynasties are more politically active than poor dynasties, social spending for public education should be lower and therefore income mobility should be lower.”50

Rent seeking is identified as being exacerbated by poor institutions, and undermines pathways for the many to engage in a broad-based, inclusive prosperity that lifts intergenerational income mobility rates. An appreciation of the problems posed by lax institutional quality also brings nuance to the connection between inequality and mobility that is foregrounded by the Great Gatsby curve. As noted in a range of recent studies, normative perceptions of inequality are partly informed by questions of fairness.51 That is, people will accept a relatively higher degree of inequality if they believe the underlying institutional, and other, processes that generated it are deemed to be fair.

Similarly, a high degree of mobility (in this case, intergenerational mobility between parents and their offspring) may attenuate concerns about inequality, because of the view that equality of opportunity operates in such a way as to improve the economic position of future generations. Conversely, institutions that are viewed as being complicit in closing mobility and economic opportunities are, in turn, likely to be perceived as promoting unfair inequality.

What does the available empirical literature tell us about the institutional implications of intergenerational mobility? There is a relatively limited number of studies centrally devoted to answering this question, although there are now a few contributions that use a variety of datasets to explore the nature of the association between institutional quality and intergenerational mobility. These studies include Australian data as part of broader investigations into the international dimension of the issues. It should be noted that Australia tends to be positioned reasonably well in comparison with other countries on various indicators of institutional quality. The assumption here is that further improvement in rated performance regarding institutional quality is likely to further enhance the intergenerational income mobility prospects of younger Australians.

In a 2014 study for the Journal of Institutional Economics, Christopher Boudreaux appraises the effect of institutional quality upon intergenerational income mobility.52 While recognising that the Great Gatsby curve has lent itself to policy recommendations to bolster mobility through greater governmental spending on transfer programs and social services, Boudreaux seeks to investigate the alternative hypothesis that income mobility is “supported through high quality institutions that facilitate entrepreneurship and the protection of property rights.”53

Indeed, “private property rights, free enterprise, and sound money foster an environment where subconscious learning can occur and the alert entrepreneur discovers these profitable opportunities. Excessive regulations — which curtail business activity and consequently make it harder for young people, and others tending to command lower incomes, to become entrepreneurs — are also considered as barriers to increasing income mobility. If this is true, removing some of these barriers, regulations, and red tape are posited to improve income mobility.”54 The implication of this alternative hypothesis, if supported by empirical testing, is that greater emphasis should be placed upon market liberalisation as the core strategy to lift income mobility rates for young people (and others).

Boudreaux uses a range of indicators from publicly-available datasets as proxies for institutional quality. These include the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators for regulatory quality, government effectiveness, and the rule of law, and Transparency International’s indicator for corruption.

Corak’s estimates of the intergenerational income elasticity for 25 countries, including Australia, are used as the dependent variable in Boudreaux’s regression analysis, which covers the period from 1996 to 2006. The author finds that the Great Gatsby correlation between inequality and intergenerational mobility still holds, but the inclusion of institutional quality variables has statistically significant effects with respect to mobility: “[t]he empirical estimates in this study suggest that lack of corruption and secure property rights are associated with reductions in intergenerational earnings persistence, which leads to greater income mobility.”55

Similar results are found when Boudreaux uses institutional quality indicators contained in the Fraser Institute’s economic freedom index.

In the Fraser Institute’s 2021 index, Justin Callais and Vincent Geloso also investigate the relationship between institutional quality and mobility.56 The authors discuss a variety of channels through which better institutions translate into greater intergenerational income mobility — such as the incentivisation provided by more secure property rights to invest in skills, and the effect of lower taxes and less burdensome regulations in promoting gains from entrepreneurial efforts and other investments.57 On this occasion, Callais and Geloso use alternative mobility datasets as well as relying upon a greater sample of 82 countries (including Australia) than Boudreaux’s 25.

The Callais-Geloso empirical framework uses mobility datasets from the World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Social Mobility Index, and the World Bank’s Global Database on Intergenerational Mobility. Overall, the authors find “fairly robust evidence that economic freedom is generally linked to social mobility,”58 with the correlation between freedom and mobility being more robust for the WEF index (with a larger sample of countries in its dataset) than the World Bank’s index. Performing empirical tests on disaggregated sub-components of the WEF index reveals that the quality of the legal system and property rights appears to largely inform the positive correlation between economic freedom and income mobility.

Callais’ recent paper for the U.S.-based Archbridge Institute investigates the direction and strength of the correlation between institutions and intergenerational income mobility, with a cross-country analysis (including Australian data).59 The paper refers to mobility figures from the World Bank’s Global Database on Intergenerational Mobility dataset. For proxy measures of institutional quality, the study draws upon a ‘legal systems and property rights’ index as part of the Fraser Institute’s economic freedom assessments.60 The study also uses a rule of law index from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators dataset, together with a corruption index from the Political Risk Service’s ‘International Risk Country Guide.

Callais’ analysis regressing the mobility measurement against Fraser Institute’s index and additional control variables — such as life expectancy, urban population share, and total population — found a statistically significant relationship between higher institutional quality and less income persistence. His subsequent extended regression analysis using sub-components of the Fraser index found a statistically significant relationship with intergenerational income mobility: “legal system integrity … has the biggest impact on mobility. However, all components have a large and strong correlation with income mobility.”61 An additional regression analysis using the rule of law and corruption indicators showed a strong negative correlation between the institutional quality indicators and the measure for intergenerational income persistence. All in all, Callais says, there is “quite robust evidence between legal systems, property rights protection, controlling corruption, and mobility.”62

To summarise, it is important to consider the bigger picture of those multiple factors that are considered to drive income mobility, or the lack thereof, across the generations. While it is intuitively plausible to consider that an unequal income distribution can influence mobility — for example, through the deprivation of resources and investment opportunities for young people in poorer households — we should not infer that inequality is the monocausal driver of intergenerational mobility. Theoretical and empirical developments in economics over recent decades would point to the quality of institutions as, still, an under-appreciated factor in the observed degree of income mobility between parents and their children. This perspective suggests that a host of fiscal, legal, and regulatory constraints are potentially complicit in the suppression of youth socio-economic potential. It follows that institutional and policy reforms allowing more people to access the full set of economic opportunities on offer, and to keep more of the rewards derived from productive economic activity, would help facilitate progression up the income ladder for young Australians. Forthcoming research will propose concrete reforms along these lines.

Conclusion

Australia’s future greatly depends upon fulfilling the intergenerational promise of giving our young people a better future. Efforts to improve mobility outcomes across the generations are crucial to building prosperity in the years and decades to come, and to give young Australians the means to address the challenges, and grasp opportunities, that loom ahead. Intergenerational mobility is also crucial to realise this country’s elemental socio-political promise of fulfilling aspiration and achieving life satisfaction. Any person, irrespective of their background and life experience, should not be trapped in their circumstances. Indeed, every person should be at liberty to progress in life to its fullest bounds. Is it legitimate that Australians use their abilities and talents to accomplish their dreams for a better future? If the answer to such a question is “yes,” then it stands to reason that we aspire to a high-mobility economy and society for future generations — our Generations Next.

Australia performs reasonably well in international comparisons of intergenerational income mobility. This implies that, compared to many of their peers in comparable advanced economies, young Australians are better able to access the necessary economic opportunities that lead to upward mobility — and to an extent not previously experienced by previous generations.

The observations canvassed here are not intended as a paean to complacency; far from it. All existing generations of Australians have high expectations concerning future improvements in material abundance, and the expansion of life opportunities more generally, that ought to be accessible to present-day Millennials and Gen Z’ers, and those who will follow them. Considerations of the welfare of future generations not only entail economic significance, as lucidly explained by Tyler Cowen,63 but, as previously discussed in this report, are wrapped up in broader ethical and moral concerns about a better future for all.

This report pursued an institutional approach to understanding some key restraints upon intergenerational mobility, and the kinds of reforms necessary to help young people to secure their personal aspirations, and to discover their own preferred pathways to betterment. It is posited that the capacity of young Australians to scale the ladder of income growth and economic opportunity is contingent, in no small part, to the quality of formal institutions maintained by governments. Quality in this sense concerns the extent to which legislators and policymakers commit to, and respect, the economic freedom of individuals (and, in our case, especially young people) to utilise existing means and strategies to exercise upward mobility — and, crucially, to discover new paths toward mobility through mutually beneficial, voluntary exchanges in market settings.

On an internationally comparative basis, Australia has consistently ranked highly on economic freedom measures,64 but it is important to stress that such measures are relative. This means that a lack of persistent dedication to maintain, and improve, the quality of our institutions risks diminution of economic freedom. The concern raised in this report is that such outcomes could compromise strong intergenerational income mobility outcomes in future years. This proposition, to the extent it prevails, dovetails disconcertingly with a range of assessments concluding Australia has indulged in reform complacency over the past few years, if not the past decade.65 I will reserve specific discussions about institutional and key public policy reforms for a subsequent paper. For now, the generic point is made that reform would be expected to not only bolster intergenerational mobility rates in this country but, in its own right, further enhance the condition of what are reasonably functional (though imperfect) institutions on an internationally comparative basis.

Institutional reforms that expand economic freedom, which, in turn, empowers young people to find their best avenues to long-term material improvements — as well as reduce incentives to politically capture economic conditions to the exclusion of the young — are clearly key to intergenerational mobility. The implication is that reforms that empower young people to engage with diverse economic situations, and discover their preferred pathways to upward mobility, will best harness their talents and future prospects.

Hence, pro-mobility institutional reforms will provide future generations with a robust basis for betterment. It is time to loosen the chains that bind intergenerational mobility, and reform is the surest method to achieve this. As mentioned previously, the specification of feasible reform opportunities to enhance intergenerational mobility will be the focus of forthcoming research.

Endnotes

1 Lowies, Braam, Graham Squires, Peter Rossini and Stanley McGreal. 2021. “Locked-out: generational inequalities of housing tenure and housing type.” Property Management, doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/PM-09-2021-0067.

2 Headspace. 2020. “Coping with COVID: the mental health impact on young people accessing headspace services.” https://headspace.org.au/assets/Uploads/COVID-Client-Impact-Report-FINAL-11-8-20.pdf (accessed 25 May 2022); Munasinghe, Sithum, Sandro Sperandei, Louise Freebairn, Elizabeth Conroy, Hir Jani, Sandra Marjanovic and Andrew Page. 2020. “The Impact of Physical Distancing Policies During the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health and Well-Being Among Australian Adolescents.” Journal of Adolescent Health 67 (5): 653-661; Natasha Bita. 2022. “Teens mentally scarred by lockdowns.” The Australian, 25 May.

3 Switzer, Tom and Charles Jacobs. 2018. Millennials and socialism: Australian youth are lurching left. CIS Policy Paper No. 7.

4 Institute of Actuaries Australia. 2020. Mind the Gap – The Australian Actuaries Intergenerational Equity Index. https://www.actuaries.asn.au/Library/Opinion/2020/AAIEIIGreenPaper170820.pdf (accessed 25 May 2022); Bessant, Judith. 2019. “OK Boomer, here’s how we fix the generational war.” Sydney Morning Herald, December 5; Wood, Danielle and Kate Griffiths. 2019. “Generation Gap: Ensuring a fair go for younger Australians.” https://grattan.edu.au/report/generation-gap (accessed 25 May 2022).

5 Australian Institute for Health and Welfare (AIHW). 2006. Mortality over the twentieth century in Australia: Trends and patterns in major causes of death. AIHW cat. no. PHE73; Barro, Robert and Jong-Wha Lee. 2013. “A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World, 1950-2010.” Journal of Development Economics 104: 184-198; Abelson, Peter. 2021. “Intergenerational well-being: Baby boomers, generation X, and millennials in Australia.” ANU Crawford School of Public Policy, Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Working Paper No. 16/2021.

6 Baxter, Jennifer and Peter McDonald. 2004. Trends in home ownership rates in Australia: the relative importance of affordability trends and changes in population composition. AHURI Final Report No. 56.

7 Productivity Commission. 2021. Wealth transfers and their economic effects. Research Paper. Canberra.

8 This definition is a slight variation of that provided by the OECD (https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=7327), and which is replicated by d’Addio, Anna Cristina. 2007. “Intergenerational Transmission of Disadvantage: Mobility or Immobility across Generations? A Review of the Evidence for OECD Countries.” OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 52. OECD: Paris. A formal discussion of income mobility concepts in general is provided by Fields, Gary S. and Efe A. Ok. 1996. “The meaning and measurement of income mobility.” Journal of Economic Theory 71 (2): 349-377.

9 Stiglitz, Joseph. 2014. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.; Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. trans. Arthur Goldhammer. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; Atkinson, A. B. 2015. Inequality: What Can Be Done? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

10 McCloskey, Deirdre Nansen. 2014. “Measured, unmeasured, mismeasured, and unjustified pessimism: A Review Essay of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century.” Erasmus Journal for Philosophy and Economics 7 (2): 73-115; Geloso, Vincent and Phillip Magness. 2020. “The Great Overestimation: Tax Data and Inequality Measurements in the United States, 1913-1943.” Economic Inquiry 58 (2): 834-855; Geloso, Vincent, Phillip Magness, John Moore and Philip Schlosser. 2022. “How Pronounced is the U-Curve? Revisiting Income Inequality in the United States, 1917-60.” Economic Journal, doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueac020.

11 Solon, Gary. 1992. “Intergenerational Income Mobility in the United States.” American Economic Review 82 (3): 393-408; Björklund, Andreas and Markus Jäntti. 1997. “Intergenerational Income Mobility in Sweden Compared to the United States.” American Economic Review 87 (5): 1009-1018; Chetty, Raj, David Grusky, Maximilian Hell, Nathaniel Hendren, Robert Manduca and Jimmy Narang. 2017. “The fading American dream: Trends in absolute income mobility since 1940.” Science 356 (6336): 398-406; Corak, Miles. 2013. “Inequality from generation to generation: the United States in comparison.” In The Economics of Inequality, Poverty, and Discrimination in the 21st Century, (ed.) Robert S. Rycroft, 107-126. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; Deutscher, Nathan and Bhashkar Mazumder. 2021. “Measuring Intergenerational Income Mobility: A Synthesis of Approaches.” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Working Paper No. WP-2021-09. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3873653 (accessed 27 May 2022).

12 Carroll, Daniel R. and Anne Chen. 2016. “Income Inequality Matters, but Mobility is Just as Important.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. Economic Commentary No. 2016-16, p. 4.

13 Michael McBride. 2001. “Relative-income effects on subjective well-being in the cross-section.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 45: 251-278; Nikolaev, Boris and Ainslee Burns. 2014. “Intergenerational mobility and subjective well-being – Evidence from the general social survey.” Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 53: 82-96.

14 Winship, Scott. 2017. “Social Mobility is Still Going Strong in the Land of Opportunity.” Archbridge Institute. https://www.archbridgeinstitute.org/social-mobility-is-still-going-strong-in-the-land-of-opportunity (accessed 27 May 2022); Arends, Brett. 2018. “The so-called American Dream is way easier to achieve in Australia.” New York Post, November 28. https://nypost.com/2018/11/28/the-so-called-american-dream-is-way-easier-to-achieve-in-australia (accessed 27 May 2022).

15 Wilkie, Joann. 2007. “The role of education in enhancing intergenerational income mobility.” Treasury Roundup 2007 (4): 81-100; Dang, Trung and Jason Tian. 2019. “A measurement of intergenerational mobility in Australia.” Victoria’s Economic Bulletin 3: 25-42.

16 Leigh, Andrew. 2007. “Intergenerational Mobility in Australia.” B. E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 7 (2): 1-26. Leigh notes that adjusting for potential methodological biases provides an elasticity range for Australia of between 0.2 and 0.3, and between 0.4 and 0.6 for the United States.

17 Ibid., p. 11.

18 Mendolia, Silvia and Peter Siminski. 2016. “New Estimates of Intergenerational Mobility in Australia.” Economic Record 92 (298): 361-373.

19 Corak, Miles. 2013. “Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27 (3): 79-102.

20 Mendolia and Siminski, op. cit., p. 372.

21 Huang, Yangtao, Francisco Perales and Mark Western. 2016. “A land of the ‘fair go’? Intergenerational earnings elasticity in Australia.” Australian Journal of Social Issues 51 (3): 361-381.

22 Murray, Chelsea, Robert Graham Clark, Silvia Mendolia and Peter Siminski. 2018. “Direct Measures of Intergenerational Income Mobility for Australia.” Economic Record 94 (307): 445-468.

23 Fairbrother, David and Renuka Mahadevan. 2016. “Do Education and Sex Matter for Intergenerational Earnings Mobility? Some Evidence from Australia.” Australian Economic Papers 55 (3): 212-226.

24 Ibid., p. 219.

25 Dang and Tian, op. cit.

26 Deutscher, Nathan and Bhashkar Mazumder. 2020. “Intergenerational mobility across Australia and the stability of regional estimates.” Labour Economics 66: 101861.

27 Ibid., p. 9.

28 Kennedy, Tomas and Peter Siminski. 2022. “Are We Richer than Our Parents Were? Absolute Income Mobility in Australia.” Economic Record 98 (320): 22-41.

29 Corak, op. cit.; Greeley, Brendan. 2013. “The Gatsby Curve: How Inequality Became a Household Word.” Bloomberg, 13 December, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-12-12/the-gatsby-curve-how-inequality-became-a-household-word (accessed 5 June 2022); Corak, Miles. 2016. “How The Great Gatsby Curve got its name.” https://milescorak.com/2016/12/04/how-the-great-gatsby-curve-got-its-name (accessed 5 June 2022).

30 Corak, Miles. 2020. “Intergenerational Mobility: What Do We Care About? What Should We Care About?” Australian Economic Review 53 (2): 230-240.

31 Ibid., p. 232.

32 Ågerup, Martin and Carl-Christian Heiberg. 2021. “Inclusive Growth and Income Mobility from a Dynamic Perspective.” In Climbing the Ladder or Falling Off It? Essays on Economic Mobility in Europe, (ed.) Gonzalo Schwarz, 66-107. Madrid, Spain: LID Editorial, p. 91.

33 Knight, Frank H. 1935. The Ethics of Competition, and Other Essays. London: Allen & Unwin.

34 Becker, Gary S. and Nigel Tomes. 1979. “An Equilibrium Theory of the Distribution of Income and Intergenerational Mobility.” Journal of Political Economy 87 (6): 1153-1189.

35 Corak, Miles. 2013. “The Great Gatsby Curve: Inequality and the End of Upward Mobility.” PBS News Hour, July 15. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/the-great-gatsby-curve-inequality-and-the-end-of-upward-mobility (accessed 5 June 2022). In stating that “the curve is open to alternative interpretations in part because it is not a causal relationship,” Corak goes on to suggest that certain underlying insights offered by the Great Gatsby Curve construct should not be dismissed on the basis that correlation does not imply causation. As indicated in this section, researchers, such as Corak, have identified channels through which inequality and mobility are conceived to relate.

36 Arnott, Robert, William Bernstein and Lillian Wu. 2015. “The Myth of Dynastic Wealth: The Rich Get Poorer.” Cato Journal 35 (3): 447-485; Delsol, Jean-Philippe, Nicolas Lecaussin and Emmanuel Martin. 2017. Anti-Piketty: Capital for the 21st Century. Washington DC: Cato Institute.

37 Setzler, Bradley J. 2014. “Is the Great Gatsby Curve Robust? Comment on Corak (2013).” http://jenni.uchicago.edu/econ350/slides/Corak-Comment_2014-01-15a_bjs.pdf (accessed 5 June 2022); Winship, Scott. 2015. “Has Rising Income Inequality Worsened Inequality of Opportunity in the United States?” Social Philosophy and Policy 31 (2): 28-47.

38 For a recent summary about education and its effects upon intergenerational income mobility, see Durlauf, Steven N., Andros Kourtellos and Chih Ming Tan. 2022. “The Great Gatsby Curve.” Annual Review of Economics, https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-economics-082321-122703 (accessed 9 August 2022).

39 Becker and Tomes, op. cit., p. 1178.

40 For discussions about effective marginal tax rates in the Australian context, see, for example, Productivity Commission. 2015. Tax and Transfer Incidence in Australia. Working Paper. Canberra; Stewart, Miranda and Peter Whiteford. 2018. “Balancing Efficiency and Equity in the Tax and Transfer System” In Hybrid Public Policy Innovations: Contemporary Policy Beyond Ideology, (eds.) Mark Fabian and Robert Breunig, 204-231. New York: Routledge.

41 Pech, Jocelyn and Frances McCoull. 2000. “Transgenerational welfare dependence: Myths and realities.” Australian Social Policy 2000/1: 43-68; Cobb-Clark, Deborah. 2019. “Intergenerational transmission of disadvantage in Australia.” In AIHW. Australia’s Welfare 2019 Data Insights, cat. no. AUS226, 29-48, Canberra; Parliament of Australia. 2019. Living on the Edge: Inquiry into Intergenerational Welfare Dependence. House of Representatives Select Committee on Intergenerational Welfare Dependence. Canberra.

42 Productivity Commission. 2018. Rising inequality? A stocktake of the evidence. Research Paper. Canberra.

43 Lindbeck, Assar and Sten Nyberg. 2006. “Raising Children to Work Hard: Altruism, Work Norms, and Social Insurance.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 121 (4): 1473-1503; Barón, Juan D., Deborah A. Cobb-Clark and Nisvan Erkal. 2015. “Welfare receipt and the intergenerational transmission of work-welfare norms.” Southern Economic Journal 82 (1): 208-234; Rehbinder, Caspian and Erik Liss. 2021. “Raising the Ladder: Increasing Income Mobility with Institutions and Incentives.” In Schwarz, op. cit., pp. 13-65.

44 It should also be recognised that inequality itself is a process, as influenced by the interactions between diverse economic actors, rather than an end-state, or fixed, phenomenon. See Novak, Mikayla. 2018. Inequality: An Entangled Political Economy Perspective. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

45 Rehbinder and Liss, op. cit., p. 17.

46 There are numerous anecdotal accounts of rent seeking behaviour impacting upon market operations and policy processes in the Australian context. Examples of such concerns raised in recent years include Banks, Gary. 2013. “Return of the Rent-Seeking Society?” Economic Papers 32 (4): 405-416, and Murray, Cameron K. and Paul Frijters. 2017. Game of Mates: How Favours Bleed the Nation. Brisbane: Publicious Pty. Ltd. For a critique of the Murray-Frijters proposition that Australia’s economy is rigged by a “game of mates” process of political favouritism, see Tunny, Gene. 2017. “Review of Cameron K. Murray and Paul Frijters Game of Mates: How Favours Bleed the Nation.” Policy 33 (3): 59-62.

47 Tullock, Gordon. 1967. “The Welfare Costs of Tariffs, Monopolies and Theft.” Western Economic Journal 5 (3): 224-232; Krueger, Anne O. 1974. “The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society.” American Economic Review 64 (3): 291-303.

48 Baumol, William J. 1990. “Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive.” Journal of Political Economy 98 (5): 893-921.

49 Callais, Justin. 2022. Economic Mobility, the Rule of Law, and Property Rights Protection: Evidence from the United States and around the World. Archbridge Institute, pp. 3, 5.

50 Ichino, Andrea, Loukas Karabarbounis and Enrico Moretti. 2011. “The Political Economy of Intergenerational Income Mobility.” Economic Inquiry 49 (1): 47-69, p. 49.

51 Starmans, Christina, Mark Sheskin and Paul Bloom. 2017. “Why people prefer unequal societies.” Nature Human Behaviour 1 (4): Art. 0082; Horwitz, Steven. 2020. “Growth, inequality, and unfairness: Comparing the progressive and classical liberal perspectives.” In Capitalism and Inequality: The Role of State and Market, (eds.) G. P. Manish and Stephen C. Miller, 61-81. New York: Routledge.

52 Boudreaux, Christopher. 2014. “Jumping off the Great Gatsby curve: how institutions facilitate entrepreneurship and intergenerational mobility.” Journal of Institutional Economics 10 (2): 231-255.

53 Ibid., p. 250.

54 Ibid., p. 244.

55 Ibid., p. 250.

56 Callais, Justin T. and Vincent Geloso. 2021. “Economic Freedom Promotes Upward Income Mobility.” In Economic Freedom of the World: 2021 Annual Report, (eds.) James Gwartney, Robert Lawson, Joshua Hall and Ryan Murphy, 189-209. Vancouver, Canada: Fraser Institute.

57 Callais and Geloso recognise that the size of government may have counteracting effects on mobility. On the one hand, redistribution may assist in the accumulation of human capital, especially amongst those on lower incomes, but, on the other, taxes may discourse pro-mobility investments.

58 Callais and Geloso, op. cit., p. 206.

59 Calais, op. cit.

60 The Callais analysis includes a gender rights adjustment to the Fraser Institute data, which provides a 0-1 scale of women’s access to legal systems. However, results from the extended regression analysis show a statistically insignificant relationship between the gender rights adjustment index and intergenerational income mobility, once additional independent variables are included.

61 Callais, op. cit., p. 12.

62 Ibid., p. 15.

63 Cowen, Tyler. 2018. Stubborn Attachments: A Vision for a Society of Free, Prosperous, and Responsible Individuals. San Francisco: Stripe Press, ch. 4.

64 Gwartney, James, Robert Lawson, Joshua Hall and Ryan Murphy. 2021. Economic Freedom of the World: 2021 Annual Report. Vancouver, Canada: Fraser Institute.

65 Switzer, Tom. 2020. “Urgent case for reform.” Ideas@TheCentre, May 21. https://www.cis.org.au/commentary/opinion/urgent-case-for-reform (accessed 7 June 2022); Banks, Gary. 2020. “Not ‘wasting the crisis.’” Ideas@TheCentre, May 7. https://www.cis.org.au/commentary/opinion/not-wasting-the-crisis (accessed 7 June 2022); Carling, Robert. 2017. From Reform to Retreat: 30 Years of Australian Fiscal Policy. CIS Occasional Paper No. 161; Kasper, Wolfgang. 2015. The Case for a New Australian Settlement: Ruminations of an Inveterate Economist. CIS Occasion Paper No. 141.