A shorter path to teaching: Exploring one-year postgraduate qualifications – Executive Summary

Australia faces major teacher workforce challenges, especially in STEM subjects and rural schools. In recent years, the number of commencing Initial Teacher Education (ITE) students has been lower in most jurisdictions than in previous times. Australia’s education ministers are in the process of producing a series of actions to address teacher workforce challenges — including both recruitment and retention. It is likely that a range of policy measures will be required to sufficiently meet these challenges.

One key policy measure that could support improved teacher supply is the (re)creation of one-year postgraduate teaching pathways. Until recently, the one-year Graduate Diploma in Education (the ‘DipEd’) was the most popular postgraduate option for ITE. It is estimated around 60,000 of Australia’s teachers hold a DipEd. However, coinciding with a 2014 review, this one-year qualification was phased out, and a new requirement was introduced mandating postgraduate ITE programs be equivalent to at least two years of full-time study. This means prospective postgraduate ITE students are required to complete a two-year qualification, rather than one year.

The evidence base for this decision was weak and poorly documented. It appears no consideration was given to research showing a mixed relationship between length of pre-service training and teacher effectiveness, nor to international examples of high-achieving education systems that offer one-year teaching pathways.

Additionally, since the policy change took place, a range of measures has been introduced to boost standards for graduating teachers — including academic entry thresholds, literacy and numeracy tests, and teacher performance assessments. If the rationale for the two-year requirement was to increase standards, this reason has now been addressed through other policy initiatives.

The two-year requirement is a major disincentive for mid-career professionals looking to become teachers, as it represents a doubling of their student debt, foregone income, and time spent balancing study, work, and family commitments. Multiple reviews have recommended removing this two-year requirement, including the Commonwealth Government’s Quality Initial Teacher Education Review (September 2022), the NSW Productivity Commission’s White Paper (June 2021), and the NSW Legislative Council education committee’s Report of the inquiry into teacher shortages in New South Wales (November 2022). The policy has also been supported by the Federal Opposition, Catholic Schools NSW, and many principals and teachers.

The authority for any changes in this policy area lies with each state or territory’s Teacher Regulatory Authority (TRA), which manages accreditation of ITE programs at universities within their jurisdiction. Although some TRAs have linked the approval of ITE programs to national standards (set by AITSL), in other jurisdictions, TRAs could lift the two-year requirement, allowing local universities to offer one-year pathways.

At a federal level, the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) sets national or agreed cross-jurisdictional accreditation standards for ITE programs. AITSL lifting their two-year requirement would encourage individual TRAs to follow suit. Though not sufficient on its own, creating a standards-based one-year postgraduate teaching pathway is an important and necessary step to help improve Australia’s teacher supply.

History

Initial Teacher Education (ITE) has changed markedly in Australia over the last 40 years. It has shifted from taking place in teaching colleges, to Centres of Excellence or Colleges of Advanced Education, to eventually being absorbed into universities. Over the years, qualifications and standards for teaching have gradually become more formalised, with legislation such as the NSW 2004 Teacher Accreditation Act, and the establishment of the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) in 2009.

In recent decades, universities offered the Graduate Diploma in Education (the ‘DipEd’) as a one-year pathway into teaching. This pathway was the most popular postgraduate option. In 2013, 19% of students commencing ITE enrolled in the DipEd, compared to only 14% choosing a Masters. However, around 2014, universities were phasing out any one-year pathways such as the DipEd, coinciding with the Teacher Education Ministerial Group’s report ‘Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers’ that encouraged the introduction of the two-year Master’s requirement, and AITSL’s ITE accreditation standards formalising that requirement in 2015.

By 2016, the DipEd was no longer offered in Australia, although some legacy students remained who enrolled before the policy change. As summarised in the 2021 Quality ITE Review Discussion Paper:

“The new national approach to the accreditation of ITE programs introduced in 2011 included the requirement that all postgraduate programs be two years in duration. This change, with phased implementation from 2013, has resulted in the removal of ITE Graduate Diploma programs, which were typically one year long.”

The rationale for this policy change was not well-documented, although the main justification appeared to be that ‘high-achieving’ systems (as measured by PISA results) such as Finland had these two-year Master’s requirements.

Teacher shortages

The issue has come to prominence due to concerns around teacher shortages, particularly in STEM subjects and rural schools. AITSL’s 2021 ‘National Teacher Workforce Characteristics Report’ found Mathematics was taught by ‘out-of-field’ teachers 40% of the time. Out-of-field teaching in Australia is high by international standards. Nearly one in four Year 8 students are taught mathematics by teachers who have not majored in mathematics, compared to the international average of one in 10. For science, 9% of Year 8 students are taught by teachers who have not majored in science.

Teacher shortages are higher in rural schools than metropolitan schools. For example, May 2021 data from NSW public schools showed a vacancy rate for permanent teachers of 1.7% for schools in major cities and inner regional areas, but 4.2% for schools in outer regional and remote areas.

While there is general consensus on the discipline-specific and geographic-specific shortages of teachers, there is more contention around the extent of system-wide shortages. For example, the Commonwealth Government’s Issues Paper: Teacher Workforce Shortages stated:

“High-level modelling …indicates that between 2021 and 2025, the demand for secondary school teachers is projected to exceed the number of new graduate teachers by approximately 4,100 teachers.”

The paper ascribed these shortages to “strong growth” in student enrolments, declining ITE enrolments, and an ageing teacher workforce. However, Glenn Fahey’s report Teacher workforce: fiction vs fact noted that enrolment growth is projected to slow over the next decade following post-COVID population growth patterns and declining fertility rates. The report also notes that OECD data shows Australia has relatively low teacher shortages compared to other countries.

A pressing and widely acknowledged issue is the low ITE completion rates. The most recent data shows completion rates of only 55% for undergraduate teaching degrees, and 76% for postgraduate teaching degrees. Overall, as Education minister Jason Clare has noted: “Teacher shortage is a key issue for all States, Territories and sectors.” Thus, governments and school systems are looking for ways to increase both the enrolments and completion rates of students in teaching degrees.

Calls for one-year pathways

A number of government reviews and initiatives have supported introducing one-year postgraduate teaching pathways. The Commonwealth Department of Education’s Report of the Quality Initial Teacher Education Review [QITE] (October 2021) recommended:

“The prior learning of well-qualified, suitable, mid-career changers with skills in areas of high demand should be better recognised, with the goal of reducing to one year the time taken to complete a secondary teaching qualification. Consider amending the Accreditation of Initial Teacher Education Programs in Australia: Standards and Procedures to reinstate the Graduate Diploma for highly qualified candidates.”

The NSW Productivity Commission’s White Paper: Rebooting the Economy (June 2021) recommended to:

“Review the costs and benefits of the requirement for a two-year full-time equivalent master’s program for teaching by 2021. Compare it with one-year full-time equivalent pathways.”

The NSW Legislative Council education committee’s Report of the inquiry into teacher shortages in New South Wales (November 2022), recommended:

“That the NSW Government work with the Commonwealth Government and tertiary education providers to develop a Masters of Teaching model which involves one year of university study and one year of paid in-school placement, tied to schools with identified need to increase the number of in-field teachers, where practical.”

More broadly, there have been numerous ‘ground-level’ examples of support for a one-year postgraduate pathway. Catholic Schools NSW — representing 600 schools and 261,000 students — has supported the policy, as do many principals and teachers. Finally, the federal Coalition announced in May 2022 its support for a policy to:

“Invest $13.4 million to support changes to accreditation standards, including working with state and territory governments to lead a return to the one-year Graduate Diploma of Education.” Following its transition from government to opposition, the Coalition has re-affirmed its support for this policy.

Disincentives of two-year requirement

The two-year requirement for postgraduate teaching pathways acts as a major disincentive to prospective candidates, particularly those considering a mid-career change. Compared to one-year pathways, the second year of study represents:

- Double the tuition fees (typically $4,000 a year); and

- Double the time over which the student is not earning income (typically $70,652 in first year of teaching in NSW public schools).

It is easy to understand how this can deter professionals from switching careers. Aside from the financial costs, the second year represents a doubling of the time over which they must balance any family and work commitments alongside study. Surveys of career change student teachers during their professional experience have revealed many struggle in “juggling financial, family-related and study demands”.

Recent research has directly quantified this issue. As part of the QITE review, the Behavioural Economics Team of the Australian Government (BETA) surveyed 501 young high achievers and 1,432 mid-career professionals not currently enrolled in ITE, to quantify the relative importance of various incentives related to work and study, including pay.

Among its findings:

- “… for those mid-career professionals who were open to teaching, the vast majority underestimated the length of study required to become a teacher. Even among those who are planning to become teachers, only 28 per cent knew that they would need to complete a two-year Masters.”

- “Consultation confirmed that concerns around the length of the course and loss of income while studying were significant barriers for mid-career professionals considering a career in teaching.”

- “BETA found that a condensed one-year ITE course was as attractive as a $20,000 increase in top pay, suggesting there is significant value attached to shortening the time spent out of the workforce for mid-career changers.”

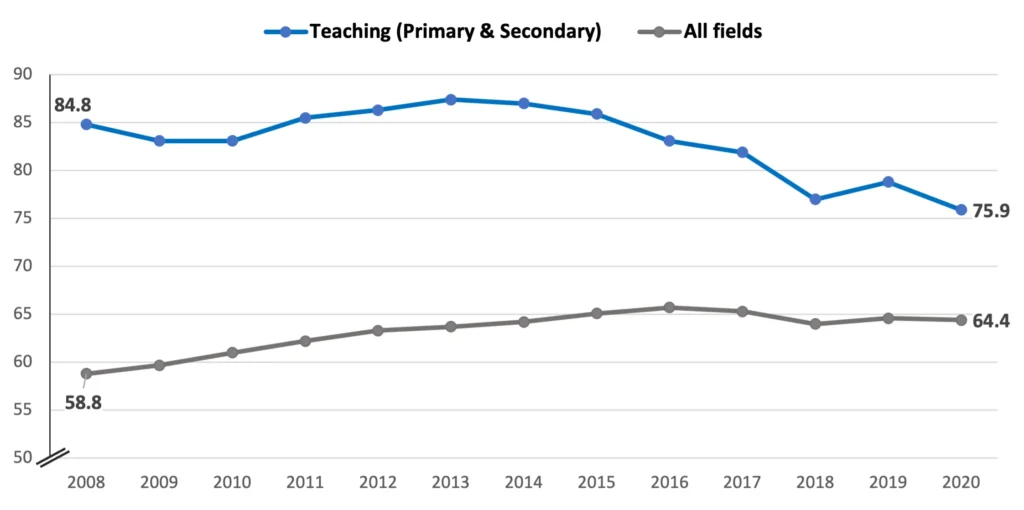

Thus, the BETA survey overwhelmingly confirmed the many, substantive disincentives of the two-year requirement, and explains why the one-year Graduate Diploma was a more popular selection prior to it being phased out. Additionally, postgraduate ITE completion rates have substantially declined since the removal of 1-year programs, at the same time as postgraduate completion rates in other fields have increased, as noted in the Quality ITE Review Discussion Paper. This could imply that the second year of study is deterring many candidates from completing the course, although it may also be related to issues with university admission standards in this field.

FOUR-YEAR COMPLETION RATES (%) FOR POSTGRADUATE COURSES, 2008-20

Source: Australia Government Department of Education, Higher Education Statistics

Limited evidence base for two-year requirement

There is limited evidence for the benefits of longer ITE pathways.

As the NSW Productivity Commission notes:

- “Australian and international evidence on higher accreditation requirements, including teacher certification, shows a mixed to weak relationship with improved student outcomes (Commonwealth Productivity Commission, 2012c). The bulk of empirical evidence, including randomised controlled trials, finds teacher certification bears little relationship to teacher effectiveness, as measured by impacts on student achievement (Decker, Mayer, and Glazerman, 2004; Gordon, Kane, and Staiger, 2006; Kane, Rockoff and Staiger, 2006; Ladd and Sorensen, 2015; Ryan, 2017).”

- “Research suggests that rather than focusing on pre-service training time, the quest for teacher effectiveness should prioritise two stronger indicators: training quality, and candidate attributes such as subject matter expertise and academic strength.”

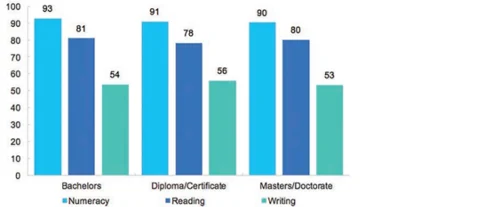

These findings extend to the Australian context. Research from Glenn Fahey analysed average student achievement gain (Year 3 to Year 5) in Numeracy, Reading, and Writing, by teachers’ highest level of qualification, and found: “Australian student data shows no difference in student progress based on differences in teachers’ qualifications.” The analysis concluded that: “Teachers’ level of teaching credentials does not appear to impact student achievement.”

Average student achivement gain (Year 3 to Year 5) in Numeracy, Reading, and Writing, by teachers’ highest level of qualification

Source: Glenn Fahey’s analysis from Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Wave 4 (K Cohort), Wave 6 (B Cohort).

Additionally, there is limited evidence that high-achieving systems require longer teaching pathways. Finland, which has a similar two-year postgraduate requirement and was the key case study behind Australia’s policy change, has seen their PISA results rapidly decline since 2006. At the same time, other high-achieving systems, such as Singapore (ranked second worldwide in PISA results), offer one-year postgraduate teaching qualifications. Many other jurisdictions also offer such pathways, including UK, New Zealand, and Hong Kong.

Finally, no evidence has been put forward of any differences in quality between teachers with one-year qualifications and those who went through longer pathways. Given the size of this group, it is obvious that any systemic deficiencies in their training could not have remained hidden to date. More than 60,000 Australian teachers hold a DipEd, according to AITSL’s 2018 survey for their ‘National Teacher Workforce Characteristics Report’, accounting for 29% of secondary teachers (~42,000) and 12% of primary teachers (~18,000). No analysis has ever suggested these teachers’ work to be of inferior quality to that of their peers.

No change in standards

Recent discussions around introducing one-year teaching pathways have prompted some observers to claim this would mean a drop in standards and unqualified teachers being allowed to teach. Such criticism is unwarranted. This is a change in length of qualification, not a change in standards. That is, it would most likely involve a change to the ‘Accreditation of initial teacher education programs in Australia Standards and Procedures’ but would require no change to the ‘Australian Professional Standards for Teachers’.

As summarised below, there are already a range of measures applying standards that would remain unaffected by any creation of one-year teaching pathways. These measures include:

- Literacy and Numeracy Test for Initial Teacher Education (LANTITE) — compulsory assessment for ITE students on literacy and numeracy, with the passing threshold equivalent to being within the top 30% of the general population.

- Teaching Performance Assessments (TPA) — compulsory assessment of practical skills and knowledge of ITE students.

- Minimum ATARs or Year 12 results in selected jurisdictions (e.g. minimum 70 in Victoria, three Band 5s in NSW).

- Minimum GPAs in selected jurisdictions (e.g. Credit average in NSW).

- Ongoing Professional Learning requirements (e.g. 100 hours per five years in NSW).

Notably, most of these measures were brought in or expanded after one-year teaching pathways began being phased out in 2014. Thus, the standards of any new one-year teaching pathway would be much higher than those present in the previous era. Ultimately, length of training is a poor proxy for teaching quality standards, particularly when so many more direct measures are now available.

A continuum of standards

Also highly relevant to a consideration of the issue of teaching standards is that AITSL has created a continuum of standards all commencing teachers can now progress through: Graduate, Proficient, Highly Accomplished, and Lead standards. Most Teacher Regulatory Authorities (TRA), such as the NSW Education Standard Authority (NESA) or the Victorian Institute of Teaching (VIT), have also adopted such continuums.

This means it is fallacious to conduct the teacher quality argument on the basis that a teacher must be fully professionally formed at the point of entry to the profession. Universal entry level standards are just that — entry level. All commencing teachers must then further develop their professional knowledge and skills with the assistance of both professional mentoring and ongoing professional development courses — courses that themselves must meet objective accreditation standards.

This need for ongoing professional formation after entry to teaching has, of course, always been the case. But its implementation is now both formally structured and transparently delivered in a recognised standards-based environment; an environment that is overseen by an independent Statutory Teacher Accreditation Authority; for example, NESA in NSW, or VIT in Victoria. In this model of teacher development, the length of initial ITE preparation — while an important consideration — is not the critical variable. Rather, the critical variable is demonstrated practice assessed against objective standards.

Building on existing flexibility

Many states already offer flexible pathways into teaching — allowing some ITE students conditional accreditation to teach — for the purpose of facilitating employment-based pathways into teaching. Typically, such pathways involve paid employment at a school for the ITE student while they study for their teaching qualification. For example, the Turn to Teaching Internship Program in Queensland, the Mid-Career Transition to Teaching Program in New South Wales, or Teach for Australia operating across most states and territories. Additionally, some universities offer accelerated or ‘fast-tracked’ programs that allow ITE students to complete the two-year Masters in 18 months.

The Commonwealth Department of Education’s Draft National Teacher Workforce Action Plan (November 2022) favourably comments on such initiatives, and recommends further efforts to “Trial new ways of attracting and keeping teachers in the schools that need them most.”

These programs demonstrate it is possible to uphold teaching standards while simultaneously implementing flexible entry level pathways for teaching. The prevalence of these programs establishes that, within most states and territories, there already exists a statutory path to ITE flexibility in a standards-based environment.

Options for one-year postgraduate qualifications

There are various options available for the creation of a one-year postgraduate teaching pathway. The simplest option is the creation of a qualification similar to the Graduate Diploma in Education that was phased out by 2016. Another option is a more limited scope, with the qualification restricted to secondary teachers only.

A further option would be the qualification being targeted towards specific shortages, such as in STEM subjects or rural schools (for example, accreditation limited to teaching in rural or ‘hard-to-staff’ schools). Finally, accelerated or employment-based postgraduate pathways have been suggested as ways to place ITE students in the classroom sooner. Typically involving some form of ‘intensive study’, such programs can in some circumstances shorten the duration from 2 to 1.5 years. Such initiatives are being developed and implemented in a number of jurisdictions, including New South Wales, Victoria, Western Australia, Queensland and Tasmania.

While an incremental improvement on the status quo, the intensity and duration of such programs means they retain many of the disincentives of a conventional two-year postgraduate pathway (albeit to a lesser extent), particularly regarding financial costs and time spent balancing work and family commitments.

A more straightforward change towards a one-year postgraduate teaching qualification would still be the most effective policy change in this regard. Furthermore, it would still leave its graduates the option of pursuing a Master’s degree through one additional year’s worth of study at a later date.

Ideally, this policy change would be encouraged by AITSL, through amending their ITE accreditation standards. However, it is each state or territory’s Teacher Regulatory Authority (TRA) that ultimately decides which ITE programs are recognised within their jurisdiction. These organisations, such as NESA or VIT, could rescind the two-year requirement within their jurisdiction, thereby allowing universities within their state to offer a one-year postgraduate pathway.

Any such changes could potentially be accompanied by a change in the title of the qualification (e.g. Graduate Diploma in Teaching) to make clearer the differences in both the qualification itself and its broader context when compared to the old Graduate Diploma in Education. That is, this new qualification would be designed for the new standards-based model of teacher accreditation, rather than the old ‘time-served’ model from the previous era.

Conclusion

Given the current teacher workforce vacancies and the decline in teaching degree completions, there is an imperative for new measures to improve teacher supply. While no single measure will suffice, introducing a one-year postgraduate teaching pathway may represent the simplest, lowest-risk, and most effective of measures available to attract more people into teaching. The arguments in favour of this move are numerous and by now well-known.

- There is limited-to-no evidence for longer training pathways, either in Australia or overseas.

- Many high-achieving education systems around the world already allow and encourage such pathways.

- Within Australia, there are already 60,000 teachers with a DipEd, who have been teaching effectively for many years without complaint.

- Recent research directly shows that the additional year of training is a major disincentive to prospective mid-career changers, because of both the financial cost, and the time spent balancing family, study, and work commitments.

- The new, shortened qualification would be operating safely within a growing, standards-based environment of academic entry thresholds, literacy and numeracy tests, teacher performance assessments, and ongoing professional learning requirements.

- The policy has already been considered in detail and recommended by a host of government reviews, parliamentary inquiries, and education stakeholders.

- The change does not require new legislation or additional funding, but could instead be immediately implemented by some state or territory TRAs, or advanced federally by AITSL.

Ultimately, while only one of many necessary measures in this space, the one-year postgraduate teaching pathway would be a welcome and necessary reform, and a rare example of a ‘quick win’ in public policy.

Appendix

Comparison of course structure between diploma and masters in ITE

Sample comparison for a student aspiring to teach Chemistry in secondary schools.

|

Graduate Diploma University of Technology Sydney (UTS) 2004 | 8x classes |

Masters University of Technology Sydney (UTS) 2021 | 16x classes |

|

|

Core units |

Professional Practice in the Secondary School Psychology of Secondary Students Professional Practice in Catering for Difference and Special Needs Social and Philosophical Aspects of Secondary Education |

Understanding and Engaging Adolescent Learners Learning Futures: Teaching for Complexity and Diversity Professional Learning Literacy and Numeracy Across the Curriculum Inclusive Education Teaching and Learning with Digital Technologies Resetting the Future: Indigenous Australian Education |

|

Curriculum units |

Learning in Science 1 Learning in Science 2 Professional Practice in Science 1 Professional Practice in Science 2 |

Science Teaching Methods 1 Chemistry Teaching Methods 2 Chemistry Teaching Methods 3 Professional Experience Teaching Practice 1 Professional Experience Teaching Practice 2 |

|

Elective units |

Choose 4, for example: Teaching Across the Curriculum Aboriginal Sydney Now Education: Rights and Responsibilities Create: Creating Interactive Multimedia Objects |

References

O’Donoghue, T. (2018) ‘Teacher education in Australia in uncertain times’, Education Research and Perspectives, https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/docview/2215484156?pq-origsite=primo

NESA (2021), ‘Registration requirements: Teaching staff’, https://rego.nesa.nsw.edu.au/registered-indivizdual-non-government-schools/registration-requirements/staff/teaching-staff

AITSL (2020), ‘National Initial Teacher Education Pipeline: Australian Teacher Workforce Data Report 1’, https://www.aitsl.edu.au/research/australian-teacher-workforce-data/atwdreports

TEMAG (2014), ‘Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers’, https://www.aitsl.edu.au/tools-resources/resource/action-now-classroom-ready-teachers

AITSL (2015), ‘Accreditation of initial teacher education programs in Australia Standards and Procedures’, https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/national-policy-framework/accreditation-of-initial-teacher-education-programs-in-australia.pdf, Standard 4.1 p15

Cervini, E. (2016), ‘Goodbye DipEd: the long and expensive road leading to teaching today’, https://www.smh.com.au/education/goodbye-diped-the-long-and-expensive-road-leading-to-teaching-today-20160509-goppgy.html

Commonwealth Department of Education (2021), ‘Quality Initial Teacher Education Review: Discussion Paper’, https://www.dese.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/announcements/quality-initial-teacher-education-review-discussion-paper

Darling-Hammond, L. (2017), ‘Teacher education around the world: What can we learn from international practice?’, European Journal of Teacher Education, https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12365/17314/Teachereducationaroundtheworld_Whatcanwelearnfrominternationalpractice.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Survey size = 17,729. Estimates calculated noting there were 296,515 FTE teaching staff in 2020.

AITSL (2021), ‘National Teacher Workforce Characteristics Report’’, https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/atwd/atwd-teacher-workforce-report-2021.pdf?sfvrsn=126ba53c_2

ACARA (2021), ‘Staff Numbers’, https://www.acara.edu.au/reporting/national-report-on-schooling-in-australia/national-report-on-schooling-in-australia-data-portal/staff-numbers

Thomson, S. et al. (2021), ‘TIMSS 2019 Australia. Volume II: School and classroom contexts for learning’, ACER, https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=timss_2019

Estimates taken by dividing teaching FTE vacancies (May 2021) by total teaching FTE (August 2020). Note estimates may overestimate vacancy rates by not taking into account growth in workforce from August 2020 to May 2021.

ACARA (2020), My School, https://www.acara.edu.au/contact-us/acara-data-access

NSW Parliament (2021), ‘LC QON5633: Teacher Shortages’, https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/hp/questionanswer/86572/LC%20QON%205633.pdf

Commonwealth Department of Education (2022), ‘Issues Paper: Teacher Workforce Shortages’, https://ministers.education.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Teacher%20Workforce%20Shortages%20-%20Issues%20paper.pdf

Fahey, G. (2022), ‘Teacher workforce: fiction vs fact’, The Centre for Independent Studies, https://www.cis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/rr43v2.pdf

“Sharp declines in Australia’s population growth rate during the Covid-19 pandemic … and historically low birth rates … mean that enrolment growth throughout the 2020s can be expected to be markedly slower than in recent decades.”

“The OECD’s Index of Shortage of Education Staff provides an international comparison of availability and quality of teaching and support staff. Of the 78 countries with comparable data, Australia is ranked around the bottom fifth — indicating that Australia experiences considerably lower levels of staff shortages compared to others… And compared to OECD countries, Australian principals report relatively low levels of shortages of teachers and non-teaching support staff…”

Six-year completion rate for undergraduate ‘Teaching – Primary & Secondary’ students commencing 2015, and four-year completion rate for postgraduate ‘Teaching – Primary & Secondary’ students commencing 2017.

Australian Government Department of Education (2022), ‘Completion Rates – Cohort Analyses’, https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/student-data/completion-rates-cohort-analyses

Clare, J. (2022), ‘Media release: National Action Plan on Teacher Shortage’, https://www.jasonclare.com.au/media/portfolio-media-releases/5170-national-action-plan-on-teacher-shortage

Commonwealth Department of Education (2021), ‘Next Steps: Report of the Quality Initial Teacher Education Review’, https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/next-steps-report-quality-initial-teacher-education-review

NSW Productivity Commission (2021), ‘Productivity Commission White Paper 2021: Rebooting the economy’, https://www.productivity.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-06/Productivity%20Commission%20White%20Paper%202021.pdf

NSW Legislative Council: Portfolio Committee No. 3 (2022), ‘Report of the inquiry into teacher shortages in New South Wales’, https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/lcdocs/inquiries/2882/Report%20No.48%20-%20PC%203%20-%20Teacher%20Shortages%20in%20NSW.pdf

Baker, J. (2021), ‘Calls for the return of the one-year teaching qualification’, The Sydney Morning Herald, https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/calls-for-the-return-of-the-one-year-teaching-qualification-20210625-p584bo.html

Morphet, J. (2021), ‘Catholic schools boss wants teachers trained within a year to stem ‘looming crisis’ shortage’, The Daily Telegraph, https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/catholic-schools-boss-wants-teachers-trained-within-a-year-to-stem-looming-crisis-shortage/news-story/7c7026f849f64a67a07bee946314c13f

Ashman, G. (2021), ‘Submission to the Australian Quality Initial Teacher Education Review’, https://fillingthepail.substack.com/p/a-better-deal-for-new-teachers

https://twitter.com/mikesalter74/status/1409111829163376640

https://twitter.com/enzuber/status/1409246540808409092

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/paulina-skerman-8a249258_calls-for-the-return-of-the-one-year-teaching-activity-6815054121532563456-VNOr/

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/mark-tannock-416080104_calls-for-the-return-of-the-one-year-teaching-activity-6815150791549161472-WcbN?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop

Robert, S. (2022), ‘Our Plan for Raising School Standards’, https://www.liberal.org.au/our-plan-raising-school-standards

“There is little evidence that the standard two years Masters is producing better outcomes than the traditional one-year diploma, but it costs the student more, and becomes an impediment for mid-career professionals to switch to teaching.”

Tudge, A. (2022), https://twitter.com/AlanTudgeMP/status/1587986170624950273

UNSW (2022), ‘Master of Teaching (Secondary)’, https://degrees.unsw.edu.au/master-of-teaching-secondary/

NSW Department of Education (2021), ‘Salary of a teacher’, https://education.nsw.gov.au/teach-nsw/explore-teaching/salary-of-a-teacher

Varadharajan, M. et al (2019), ‘Career change student teachers: lessons learnt from their in‑school experiences’, The Australian Education Researcher, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-020-00381-0

Commonwealth Department of Education (2021), ‘Next Steps: Report of the Quality Initial Teacher Education Review’, https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/next-steps-report-quality-initial-teacher-education-review

Australian Government Department of Education (2022), ‘Completion Rates – Cohort Analyses’, https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/student-data/completion-rates-cohort-analyses

Commonwealth Department of Education (2021), ‘Quality Initial Teacher Education Review: Discussion Paper’, https://www.dese.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/announcements/quality-initial-teacher-education-review-discussion-paper

Wilson, R. (2020), ‘The Profession at Risk: Trends in standards for admission to teaching degrees’, commissioned by NSW Teachers Federation, https://www.nswtf.org.au/files/20042_theprofessionatrisk_digital.pdf

In public discussions of the issue, one study (Jackson & Bruegmann, 2009) was cited in favour of longer pathways. However, this study showed the benefits of longer qualifications alongside greater experience, it did not look at longer qualifications on their own.

Additionally, the NSW Productivity Commission notes “One United States study found traditional certification did improve student outcomes (Darling-Hammond et al., 2005). However, the study’s methodology was strongly criticised, particularly for failing to appropriately control for differences in students’ socio-economic status (Podgursky, 2006).”

Darling-Hammond, L., Holtzman, D.J., Jin Gatlin, S., & Vasquez Heilig, J., (2005), ‘Does Teacher Preparation Matter? Evidence about Teacher Certification, Teach for America, and Teacher Effectiveness’, Education Policy Analysis, https://doi.org/10.14507

Podgursky, M. (2006), ‘Response to “Does Teacher Preparation Matter?”, https://www.nctq.org/nctq/research/1114011044390.pdf

Jackson, C. K., & Bruegmann, E. (2009), ‘Teaching students and teaching each other: The importance of peer learning for teachers’, National Bureau of Economic Research, http://www.nber.org/papers/w15202

NSW Productivity Commission (2021), ‘Productivity Commission White Paper 2021: Rebooting the economy’, https://www.productivity.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-06/Productivity%20Commission%20White%20Paper%202021.pdf

Commonwealth Productivity Commission (2012c), ‘Schools Workforce: Research Report’, https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/education-workforce-schools/report/schools-workforce.pdf

Decker, Paul T, Daniel P Mayer, and Steven Glazerman (2004), ‘The Effects of Teach For America on Students: Findings from a National Evaluation.’, Mathematica Policy Research, https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.487.9357&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Gordon, Robert, Thomas J Kane, and Douglas O Staiger, (2006), ‘Identifying Teachers Using Performance on the Job’, The Brookings Institution, https://www.brookings.edu/research/identifying-effective-teachers-using-performance-on-the-job/

Kane, Thomas J, Jonah E Rockoff, and Douglas O Staiger (2006), ‘What Does Certification Tell Us about Teacher Effectiveness? Evidence from New York City’, NBER Working Paper, https://www.nber.org/papers/w12155

Ladd, Helen, and Lucy C. Sorensen (2015), ‘Do Master’s Degrees Matter? Advanced Degrees, Career Paths, and the Effectiveness of Teachers’, https://caldercenter.org/sites/default/files/WP%20136_0.pdf p136

Ryan, Chris (2017), ‘Secondary School Teacher Effects on Student Achievement in Australian Schools’, Melbourne Institute, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2963380

Fahey, G. (2022), ‘Teacher workforce: fiction vs fact’, The Centre for Independent Studies, https://www.cis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/rr43v2.pdf

OECD (2019), ‘PISA 2018 Results – Country Note: Finland’, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/PISA2018_CN_FIN.pdf

OECD (2019), ‘PISA 2018 Results – Country Note: Singapore’, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/PISA2018_CN_SGP.pdf

Gair, K. (2021), ‘Fast-tracked teachers are key to improved NSW teacher quality and productivity growth’, The Australian, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/fasttracked-teachers-are-key-to-improved-nsw-teacher-quality-and-productivity-growth/news-story/5357d49b66a506dc00d9cc53afc589de

Gov.UK (2021), ‘Find postgraduate teacher training’, https://www.find-postgraduate-teacher-training.service.gov.uk/

University of Canterbury (2022), ‘Graduate Diploma in Teaching and Learning’, https://www.canterbury.ac.nz/study/qualifications-and-courses/graduate-certificates-and-diplomas/graduate-diploma-in-teaching-and-learning/

University of Hong Kong (2021), ‘Postgraduate Diploma in Education’, https://web.edu.hku.hk/programme/pgde

Survey size = 17,729. Estimates calculated noting there were 296,515 FTE teaching staff in 2020.

AITSL (2021), ‘National Teacher Workforce Characteristics Report’’, https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/atwd/atwd-teacher-workforce-report-2021.pdf?sfvrsn=126ba53c_2

ACARA (2021), ‘Staff Numbers’, https://www.acara.edu.au/reporting/national-report-on-schooling-in-australia/national-report-on-schooling-in-australia-data-portal/staff-numbers

“We need to be very careful not to reduce the quality of teachers or the status of the profession. We don’t want to give the perception that just anyone can be a teacher, or that you can do a quick program and all of a sudden you can be a teacher.” Mary Ryan, president of the NSW Council of Deans of Education

Hare, J. (2021), ‘NSW looks to university lecturers to fill school teacher jobs’, The Australian Financial Review, https://www.afr.com/work-and-careers/education/nsw-looks-to-university-lecturers-to-fill-school-teacher-jobs-20210615-p5813f

“I’ve yet to meet a parent who would prefer their child to be taught by an unqualified teacher. I doubt whether politicians, senior bureaucrats and productivity commissioners would volunteer their own children to be taught by unqualified ‘teachers’.” Angelo Gavrielatos, President NSW Teachers Federation, https://twitter.com/AGavrielatos/status/1399599952163086336

“Programs comprise at least two years of full-time equivalent professional studies…”

AITSL (2015), ‘Accreditation of initial teacher education programs in Australia Standards and Procedures’, https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/national-policy-framework/accreditation-of-initial-teacher-education-programs-in-australia.pdf, Standard 4.1 p15

AITSL (2018), ‘Australian Professional Standards for Teachers’, https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/national-policy-framework/australian-professional-standards-for-teachers.pdf

AITSL (2020), ‘Initial Teacher Education today’, https://www.aitsl.edu.au/research/spotlight/initial-teacher-education-today

ACER (2021), ‘Literacy and Numeracy Test for Initial Teacher Education Students’, https://teacheredtest.acer.edu.au/

AITSL (2021), ‘What is a teaching performance assessment?’, https://www.aitsl.edu.au/deliver-ite-programs/teaching-performance-assessment

Hare, J. (2019), ‘ATAR for teaching: all you need to know’, https://www.tes.com/en-au/jobs/careers-advice/moving-schools/atar-teaching-all-you-need-know#

Harris, C. (2020), ‘Teaching: Student teachers in NSW will face tougher uni entry requirements’, The Daily Telegraph, https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/teaching-student-teachers-in-nsw-will-face-tougher-uni-entry-requirements/news-story/32f0aa076888e669b4cfa0d576b7412c

Teach.NSW (2021), ‘Approval to teach: Pre-service teachers who commenced a teacher education course from 2019 onwards’, https://www.teach.nsw.edu.au/becomeateacher/approval-to-teach/graduates-who-commenced-their-course-in-2019

NSW Department of Education (2021), ‘Maintenance of Teacher Accreditation Policy’, https://www.educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/portal/nesa/teacher-accreditation/resources/policies-procedures/maintenance-of-teacher-accreditation-policy

AITSL (2022), ‘Understand the teacher standards: career stages’, https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards/understand-the-teacher-standards/career-stages

NESA (2022), ‘The Standards’, https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/portal/nesa/teacher-accreditation/meeting-requirements/the-standards

VIT (2022), ‘Professional Learning’, https://www.vit.vic.edu.au/maintain/requirements/learning

QLD Department of Education (2022), ‘Turn to Teaching Internship Program: Factsheet’, https://teach.qld.gov.au/scholarshipsAndGrants/Documents/ttt-fact-sheet.pdf

NSW Department of Education (2022), ‘Mid-Career Transition to Teaching Program’, https://education.nsw.gov.au/teach-nsw/get-paid-to-study/mid-career-transition-to-teaching-program

Teach for Australia (2022), ‘Where we work’, https://teachforaustralia.org/about-us/areas-we-work-in/

See Table 2. Examples of Accelerated programs, p.29 or Alternative Pathways, p29

Commonwealth Department of Education (2021), ‘Next Steps: Report of the Quality Initial Teacher Education Review’, https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/next-steps-report-quality-initial-teacher-education-review

Commonwealth Department of Education (2022), ‘Draft National Teacher Workforce Action Plan’, https://www.education.gov.au/teaching-and-school-leadership/resources/draft-national-teacher-workforce-action-plan

See Table 2. Examples of Accelerated programs, p.29 or Alternative Pathways, p29

Commonwealth Department of Education (2021), ‘Next Steps: Report of the Quality Initial Teacher Education Review’, https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/next-steps-report-quality-initial-teacher-education-review

UTS (2004), ‘2004 Handbook: Graduate Diploma in Education’, https://www.handbook.uts.edu.au/2004/edu/pg/c07103.html

UTS (2021), ‘2021 Handbook: Master of Teaching in Secondary Education’, https://www.uts.edu.au/future-students/find-a-course/master-teaching-secondary-education