Closing Opportunities, Not Loopholes: A review of the proposed new ‘Closing Loopholes’ bill and its laws regarding labour hire, casual employment, and the gig economy

Introduction – the steady reregulation of industrial relations

The Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes) Bill 2023 before Parliament, if enacted in its current form, would have adverse effects on Australia’s economy, mainly through its impacts on the economics of labour hire and digital platforms.

This is the second round of the current federal government’s Industrial Relations reforms, which broadly speaking move Australia back towards a highly-regulated labour market, partly undoing the achievements of the microeconomic reform period of the 1980s and 1990s.

The first round, the Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Secure Jobs, Better Pay) Act 2022, introduced various amendments such as making it easier for unions to initiate multi-enterprise bargaining, and abolished the Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC).[1]

However, the failure of its 2022 legislation to achieve its objectives, particularly regarding growth in real wages — which are no longer falling but remain 5% below the March 2020 level on the most commonly-used measure — motivated the government to go further.[2]

In the second reading speech for the bill, Minister for Employment and Workplace Relations Tony Burke MP made this clear, saying (regarding its 2022 Secure Jobs Better Pay legislation):

“…many Australians are not receiving the full benefit of these changes, because of loopholes that allow pay and conditions to be undercut. For these workers, the minimum standards in awards and enterprise agreements are words on a page, with little relevance to their daily lives. The businesses which use these loopholes can undercut Australia’s best employers in a race to the bottom.”

The Minister went on to call out ‘loopholes’ regarding casual employment, labour hire, and the gig economy. He also vowed to make ‘wage theft’ by employers a criminal offence, punishable by up to 10 years in prison.

The union movement strongly supports the bill. Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) Secretary Sally McManus argues ‘big business’ is “desperate to keep open the loopholes that have allowed them to keep wage growth low for so long.”[3] She is critical of the gig economy, arguing it “exists on the scale it does because of the use of these loopholes.”[4]

Unfortunately, as the productivity-sapping effect of the proposed changes will be compounded by the 2022 regulations, this bill will almost certainly have a more adverse impact than a beneficial one. As David Alexander, ACCI Chief of Policy and Advocacy, has observed, the thrust of the amendments is to further centralise, imposing ‘one size fits all’ rules, and to reduce flexibility in the labour market.[5]

This paper is structured around the core proposals examined in the bill’s Explanatory Memorandum. It will set out the government’s proposed changes and then consider each of the so-called loopholes in turn.

How the government is planning on closing the ‘loopholes’

The Bill — under review by the Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee, which will report by 1 February 2024 — will amend the Fair Work Act 2009 to close so-called ‘loopholes’ in three areas: the growth of casual employment, the expansion of labour hire arrangements, and the growth of the gig economy. Specifically, the government frames these loopholes as:

Gig economy ‘loophole’: companies such as Uber and DoorDash treat people who work for them as contractors rather than employees; meaning they do not need to pay them a minimum wage and other entitlements under an award or enterprise agreement.

Labour hire ‘loophole’: companies can source labour from labour hire companies rather than employing people directly under enterprise agreements (typically negotiated with unions), which the government criticises as a way those companies can pay less for labour.

Casual employment ‘loophole’: people can be hired as casuals even though they work regular hours and would be classified as part-time workers under the bill.

So the objectives of the bill are clear: to move people off casual, labour hire, and gig economy (i.e. independent contractor) working arrangements and into alternative working arrangements which it prefers and believes are more beneficial to workers. There is an implicit assumption that this transition can occur seamlessly without any loss of employment opportunities, which, as I further develop below, is a bold assumption likely to be incorrect. The most important measures include:

- Giving the Fair Work Commission power to set minimum standards for gig economy workers;

- Providing an objective test for casual employment and making it easier for casuals who work predictable, regular hours from week to week to apply to become a standard part-time or full-time worker with leave entitlements (ie they would not receive the casual loading of up to 25%, but would receive leave entitlements), and their employers would lose the flexibility of being able to change their hours from week to week;

- Giving the Fair Work Commission (FWC) greater powers to resolve disputes regarding casual vs part time employment;

- Forcing companies to pay labour hire employees as if they are employed under the relevant enterprise agreement; and

- Extending the right of entry of unions.

The bill has proved incredibly divisive and Minister Burke has already had to agree to change some of the more unpopular measures he originally proposed. He has agreed to clarify that it could be the case that a person working regular hours each week could still be considered a casual if they are happy with that arrangement. There was criticism of the original proposal from the hospitality sector which noted many casual workers were happy with the arrangement due to the 25% casual loading on award wage rates and the ability to refuse to work shifts.[6] There was a concern that the legislation could force them into standard work arrangements they would not prefer.

The Minister also committed to removing hefty fines for classifying what are effectively standard employment arrangements as casual in the cases where the mistake was not deliberate. Despite the changes the Minister has agreed to, the bill remains highly problematic; particularly the gig economy regulations.

Gig economy ‘loopholes’

The government is proposing to give the FWC the power to impose minimum standards for independent contractors in employee-like work, including gig economy workers and road transport workers. Several criteria are proposed to define employee-like workers on gig economy platforms, namely:

- “the person has low bargaining power in negotiations in relation to the services contract under which the work is performed;

- the person receives remuneration at or below the rate of an employee performing comparable work;

- the person has a low degree of authority over the performance of the work; or

- the person has such other characteristics as are prescribed by the regulations.”[7]

Hence, the gig economy regulations are wide in scope and could bring in workers beyond ridesharing and delivery apps; covering freelancers on platforms such as Mable, an app for finding carers.[8] It could also bring in specialist contractors who are currently paid much more than award wages. However, the Minister argues the criteria will exempt workers on AirTasker, where average earnings are considerably higher than on other gig economy platforms.[9] He says the provisions will narrowly focus on lower-paid gig economy workers — but there is considerable uncertainty about that.

Currently, gig economy workers are classed as contractors rather than employees, meaning they are not covered by the Fair Work Act and the minimum standards it imposes. Given gig economy workers can choose their own hours and will often be working for multiple platforms in a single shift (e.g. Uber or DiDi), being an independent contractor seems the most appropriate arrangement. In other words, there is no loophole.

Another serious concern is that the proposal’s impact analysis assumes gig economy regulations do not adversely affect employment. It assumes that concerns about employment impacts relate only to minimum standards regarding overtime rates and rostering.[10]

The impact analysis has ignored the high likelihood that higher standard pay rates will reduce the demand for labour, particularly as digital platforms seek to recoup some of the cost increase through higher charges for customers. This impact should have been explicitly analysed and modelled — along with the reduction in consumer benefits (or technically ‘consumer surplus’) that would occur as some consumption is choked off through higher prices. That is, consumers will lose out because they will take fewer Uber trips or order less takeaway via Menulog, for example, due to higher charges.

The impact analysis desperately attempts to downplay the impact of the increase in labour costs by comparing it with total wages and salaries in Australia; claiming it is only “0.04 per cent of total wage bill”.[11] This is extremely misleading. The comparison should have been to the current total labour costs of gig economy workers. Without this, the impact analysis is deficient.

The current analysis assumes the relevant economic transactions would occur regardless of the terms being offered, and hence, redistribution can occur with no adverse economic consequences. This is the zero-sum fallacy… the “fallacious assumption that economic transactions are a zero-sum process, in which what is gained by someone is lost by someone else.”[12] It fails to recognise: “voluntary economic transactions— whether between employer and employee, tenant and landlord, or international trade— would not continue to take place unless both parties were better off making these transactions than not making them.”[13] The government may prefer a different set of terms for those transactions; but if it imposes them, there is a risk that acceptable terms for both parties no longer overlap in many instances. Hence, total gig economy employment will fall.

Rather than the government and FWC getting involved in setting contract terms in the gig economy, it would be better to rely on the parties involved to find mutually beneficial outcomes — which could involve unions or employee groups. Earlier this year, ABC News reported that:

“Coles, Uber and the powerful Transport Workers’ Union (TWU) have signed separate “charter” agreements with each other. The Coles-TWU deal in particular promises fair rates of pay for on-demand drivers, a right to unionise and a way to arbitrate disputes, as the gig giant moves aggressively into the grocery delivery space.”[14]

It would very likely be desirable for such negotiations to take place without risking the imposition of economically-damaging arrangements by the FWC.

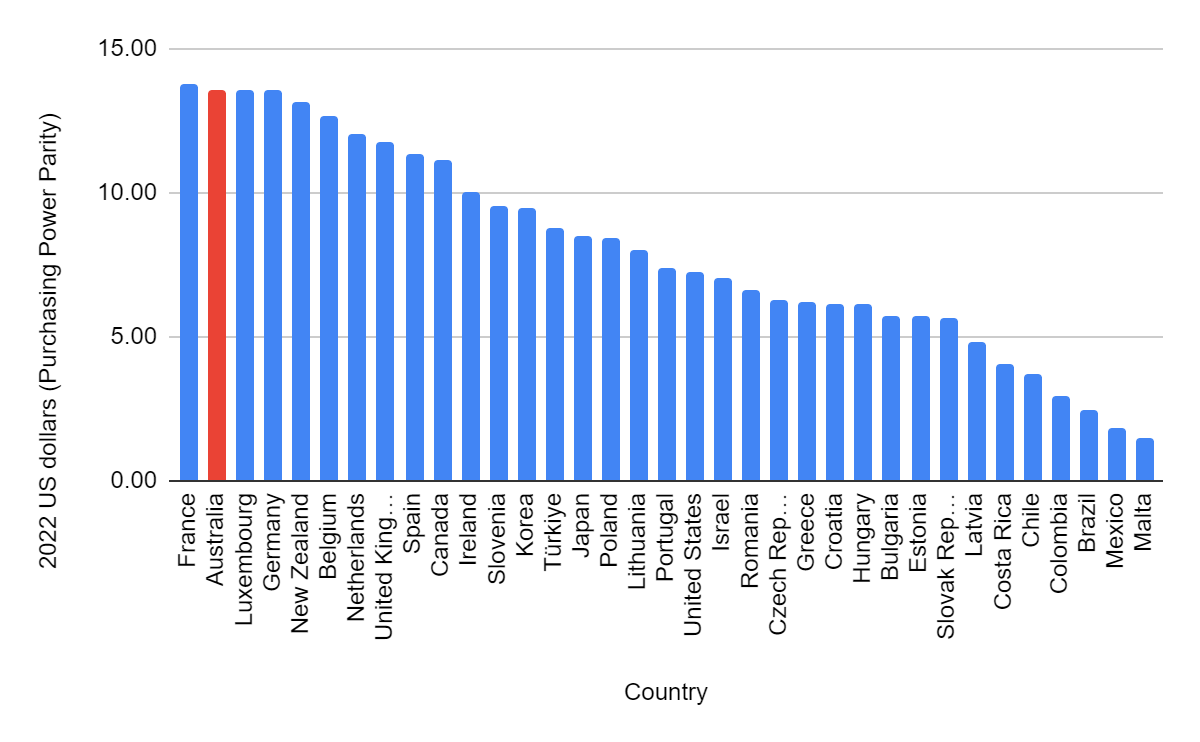

The gig economy likely provides employment opportunities for many low-skilled people who may be priced out of other employment opportunities due to Australia’s relatively high minimum wage. Australia has one of the highest minimum wages in the world, coming in second place on the OECD’s real hourly minimum wage measure, 15% higher than the United Kingdom and 86% higher than the United States (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Real minimum wages, hourly, 2022

Source: OECD, https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=RMW. Note: The chart includes data for OECD members and non-members with whom the OECD works.

Undoubtedly, the gig economy has led to strong growth in employment opportunities. For example, from 2015 to 2021, the employment of delivery drivers in Australia increased from 45,900 to 80,700, an increase of more than 75%.[15] At the same time, total nationwide employment increased by only 11%.[16]

The government should take into consideration that gig economy work is often not the worker’s sole employment opportunity and is often used to supplement other incomes; whether wages and salaries, pensions, or investment earnings. As noted by the Victorian Government Inquiry into the Victorian on-demand workforce: “Only 2.7 per cent of digital workers earned all their income from platform work.”[17] Given widespread concern over the cost of living, it would arguably be undesirable for the government to restrict the size of the gig economy — which provides many people with crucial supplementary income to help them maintain their standard of living, a point made by The Australian’s contributing economics editor Judith Sloan.[18]

This is not to deny there are gig economy regulatory issues to address. Certainly, the fatalities and injuries that gig economy workers have suffered are a cause for concern. The ACTU noted 15 delivery drivers have died on Australian roads since 2015.[19] But the government does not need to undertake such a wide-ranging intervention to address this. The road safety issue is one for local and state government transport agencies, and state workplace health and safety agencies. A lack of insurance coverage is arguably an issue. But in this case, as the Productivity Commission has recommended, any gig economy measure should directly address this issue — e.g. by requiring platform companies to seek appropriate levels of insurance for its contractors — rather than by imposing a more wide-ranging regulatory response.[20]

In any regulatory response, the overwhelming benefits of gig economy platforms to consumers need to be considered. As the Productivity Commission has observed:

“Platform business models can benefit consumers and some workers, while contributing to productivity through new and more efficiently delivered services. Regulatory challenges associated with platform work should be addressed without unduly constraining its business model.”[21]

The government needs to undertake a much more rigorous analysis of potential impacts on the gig economy; given its significant economic size following years of rapid expansion from around the middle of the last decade.

In a comprehensive study in 2020, the Actuaries Institute estimated that “Since 2015, the gig economy has grown nine-fold to capture $6.3bn in consumer spend, and to involve as many as 250,000 workers.”[22] The Institute found that while there has been some ‘cannibalisation’ of demand for the services of taxi drivers, overall there has been an expansion of the size of the private transport sector by 39% between 2015 and 2019.[23]

If the government correctly estimated the impact of its gig economy regulations, it may reasonably estimate potential losses in consumer wellbeing in the hundreds of millions — if not billions — although admittedly this is speculative.

Based on the reported hourly wage gaps (relative to award wages for related occupations) for gig economy workers in the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill, the gig economy measure could increase labour costs in the gig economy by 14-18% for delivery and ride sharing apps and 25% for platforms for carers. An increase in the former will flow through to consumers while an increase in the latter will probably end up impacting taxpayers via higher costs in the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

A back-of-the-envelope calculation can help us gauge the potential adverse impacts on employment opportunities. Assuming an average labour cost increase of 16%, and an elasticity of labour demand of -0.65, hours worked in the gig economy would decrease by 10%.[24] That would be associated with a $630 million reduction in consumer spending on gig economy services based on the $6.3 billion estimated size of the gig economy referred to previously. It may even be more than that, depending on how consumers react as higher labour costs are passed on to them, and allowing for growth in the gig economy since 2019 for which the estimate was produced.

Finally, there are substantial doubts about the practicality of implementation of the gig economy measures. It would be challenging to consider any one platform the employer of a particular gig worker since many gig workers use several platforms — often on the same shift. It is difficult to see how a minimum hourly rate of pay can be enforced in this case or, alternatively, the compliance costs would be very high, ultimately increasing prices paid by consumers.

Labour hire ‘loopholes’

As noted above, the legislation will require companies to pay labour hire employees as if they are employed under the relevant enterprise agreement. Like the gig economy measure, this proposal is framed without thoroughly considering why the so-called ‘loophole’ has arisen, or even whether it is indeed a loophole.

The government appears to have overlooked that labour hire may mean it is economically viable for employers to offer additional hours of work if they can take advantage of labour hire rates.

Or that in many instances, when the demand for labour is seasonal or temporary, it makes sense for employers to engage labour hire companies to provide the required labour.

The government must consider what might happen to total hours worked or other working conditions if the so-called loophole is closed. Regarding other working conditions, it is not only the wage that can adjust, but also other conditions — including training, and desirability of rosters — if wages are made to be equal.

Despite an increase in hourly labour rates that would occur due to the provision, as the impact analysis notes: “It is assumed there are no changes, aside from a wage increase for the eligible employees, to the working arrangements of labour hire employees.”[25]

In economic terms, the government is assuming an infinitely-inelastic demand for labour; which is impossible. Again, there are serious questions about the impact analysis. It would be desirable to obtain an impact assessment from independent economists before making such a significant change — particularly one that could adversely affect two critical sectors of Australia’s economy: mining and construction.

Industry groups, including ACCI and the Australian Resources and Energy Employer Association (AREEA), are concerned about the new labour hire rules potentially capturing a range of services provided by specialist contractors, which could make it costlier for businesses to purchase these services.[26] AREEA had expressed concern that:

“Despite public assurances made by Minister Burke, the ‘Contractor Test’ (at subsection 8(b) of Division Two of Part 6 of the Closing Loopholes Bill) does not provide an immediate and clear exemption for genuine service contractors.”[27]

However, AREEA has now done a deal with Minister Burke that it believes will address its concerns, although other industry bodies, such as the Minerals Council of Australia, are still opposed to the labour hire provisions.[28]

Overall, this measure and others in the bill could have an adverse impact on productivity, reducing business flexibility and forcing businesses to economise and employ fewer labour resources than desirable, or defer maintenance or other essential tasks. On productivity, it is logical that if new rules discourage arrangements that have enabled businesses to better tailor labour inputs to production needs, then productivity will be lessened.

Furthermore, the measure will result in additional productivity-reducing red tape. As AREEA noted in its submission, labour hire businesses could be providing labour or tendering for work at hundreds of different worksites.[29] They will need to ensure compliance at multiple sites under different enterprise agreements, with the resultant compliance burden.

Casual employment ‘loopholes’

As noted earlier, the legislation would make it easier for casuals who work predictable, regular hours from week to week to apply to become a standard part-time or full-time worker with leave entitlements; effectively making it a right, and giving the FWC greater powers to resolve disputes in this regard. It would provide an objective test for casual employment and would bring in civil penalties for incorrect classification of workers.

Incidentally, there is concern the new test could inspire class actions.[30] There is already a ‘casual conversion’ pathway under the National Employment Standards for “Casual employees who have worked for their employer for 12 months with a regular pattern of hours”, but the government believes this is insufficient and employers can too easily reject a change in employment status.[31]

It is unclear precisely what the policy problem the government is addressing regarding casual workers. Casual employment is a well-established employment arrangement that suits employers with irregular patterns of activity who need a flexible labour force, and suits employees (particularly students) who value the casual loading on pay and are willing to trade off predictability and leave entitlements. It is not a ‘loophole’ but the government is proceeding on the basis that 850,000 workers would be better classified as part-time or full-time workers and therefore eligible for leave entitlements.[32]

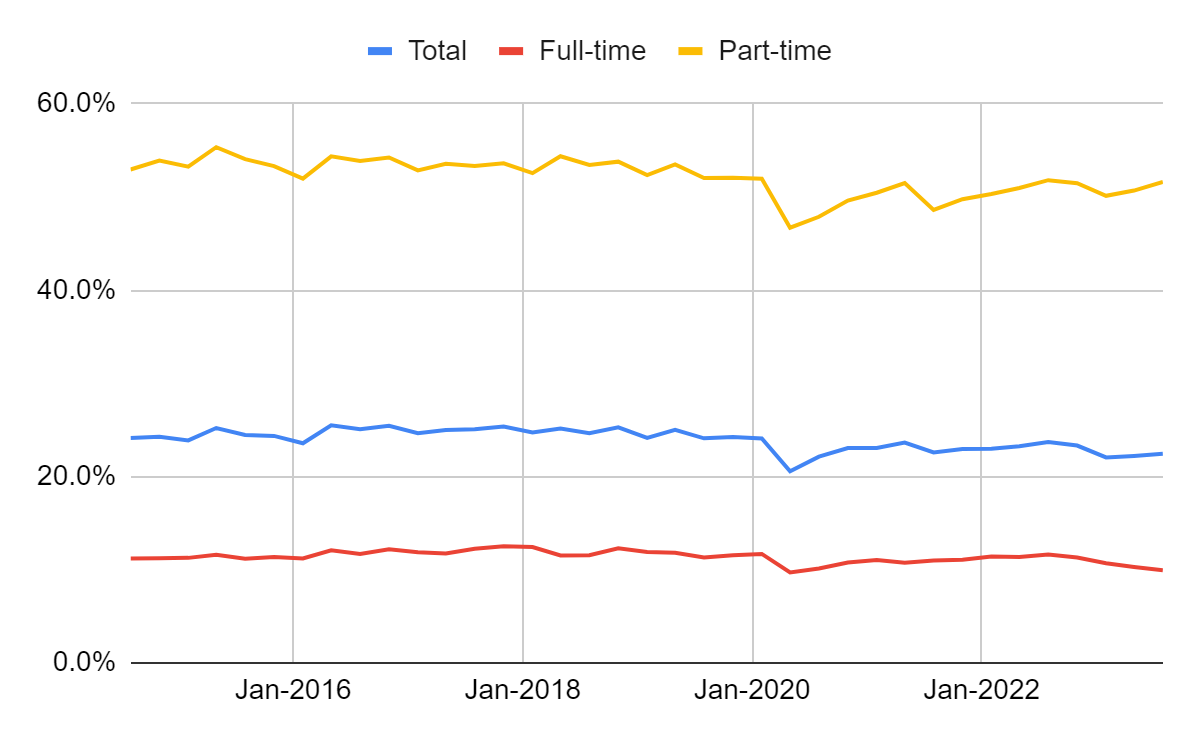

But, it is not as if the rate of casual employment has increased. Indeed, it has remained stable or slightly fallen over recent years, depending on the timeframe chosen. It was around 25% for several years in the second half of the last decade but is now around 22-23% (Figure 2).[33] So if this is a ‘loophole’ — which it is not — it is a longstanding one that has existed through previous IR regimes, including Labor’s own Fair Work Act enacted in 2009.

Figure 2. Incidence of casual employment (i.e. employees without paid leave entitlements) by type of employment, quarterly, Aug-14 to Aug-23

Source: ABS Labour Force, Australia, Detailed.

The government should be credited with acknowledging that many casual workers would prefer to remain casual even if they were eligible to apply to become permanent.[34] This recognises casual employment as a circumstance that suits many workers, mainly due to the casual loading in wages. Even if alternative employment arrangements were available, many employees would choose to remain casual.

The government’s own economic analysis of its proposal notes a majority of 63% of long-term casuals would prefer to remain casual.[35] Furthermore, the Behavioural Economics Team of the Australian Government (BETA) research it quoted found 11% were indifferent, meaning 74% of long-term casual workers do not wish to convert to a permanent position.[36]

There has not been adequate consideration of the proposal’s cost from the perspective of employers. Indeed, the government has very likely massively underestimated that cost. Again, an independent economic analysis would be helpful here.

One risk of the proposal is that it makes employers more reluctant to hire casuals if there is a risk they could become permanent employees under standard work arrangements.[37] Employers may be concerned about the lack of flexibility if they are required to guarantee ongoing employment of a certain number of hours each week.

The government is estimating the total regulatory cost of the measure over 10 years will be $8.8 million, or under $1 million in total per annum across Australian businesses.[38] This is absurdly low; particularly if one considers the tens of thousands of employers that could be affected by the change and the potential for significant HR and legal costs to be incurred if requests for permanent employment are to be reviewed or challenged.

The calculation is based on a very low assumption of the time required to deal with each application: 15 minutes for the employer and 20 minutes for each employee.[39] Anyone who has had to participate in regulatory processes — particularly new ones — would understand such processes can absorb much larger amounts of time than expected by bureaucrats. The government should provide further details on how it has derived its estimates of required time to justify its very low estimate of the regulatory burden.

Wage theft and other issues

Criminalising so-called ‘wage theft’ appears extreme, especially given the complexity of pay rates and entitlements under awards and workplace agreements — which was raised as an issue by Master Grocers Australia, for example.[40] Indeed, the Minister’s own Department of Employment and Workplace Relations has underpaid staff. The Department had underpaid around 99 employees around $60,000 from July 2022 to August 2023.[41]

While intentional underpayment would need to be proved for the criminal offence of wage theft, there is a risk that innocent employers could find themselves in legal jeopardy for innocent mistakes. It is another factor that would make it less attractive for employers to employ people. Australian Industry (Ai) Group argues the proposed approach is “an unbalanced response that does not address why the vast majority of underpayments occur.”[42] The bill has a ‘safe harbour’ provision designed to protect employers that mistakenly underpay workers, but both Ai Group and the Business Council of Australia (BCA) consider it inadequate.[43]

While intentional underpayment is required for the criminal penalty, even accidental payments can be subjected to new larger civil penalties under the bill, with penalties increasing five-fold.[44] Depending on the scale of the underpayment, penalties could range from several thousands to millions of dollars. Given the potential to capture accidental payments, these charges are excessive.

Finally, some elements of the bill are probably desirable, such as amending the Asbestos Safety and Eradication Act 2013 to deal with silica-related disease and to support its sufferers and families. This measure is related to the likely ban on the use of engineered stone which has been recommended by Safe Work Australia.[45] However, the problem with the bill is that any good measures are packaged together with a range of measures that are very likely detrimental to the economy and community. For this reason, it has been recommended by the BCA that good measures be separated from bad measures in a separate bill.[46]

Summary of likely macroeconomic impacts

Beyond the specific issues with the so-called loopholes there are fundamental issues with the approach being undertaken. The level of economic analysis of the bill’s impacts has been grossly insufficient.

Given the scale of the potential economic impacts, comprehensive cost-benefit analyses of the proposed measures should have been conducted; preferably by genuinely independent experts. The government has not demonstrated the proposed changes will deliver net benefits to the community. Indeed, the government has ignored critical adverse impacts on consumers.

It is likely that extending labour market regulations as proposed in the bill will have adverse effects on productivity and possibly also on unemployment. Various empirical studies by researchers at Australian economic agencies, such as the Reserve Bank and the Office of the Chief Economist (in the Department of Industry, Science and Resources) have found adverse impacts from labour market regulations on productivity and employment using OECD data.

Specifically, the RBA found lower levels of regulation (i.e. labour and product market regulations combined) predict higher productivity growth in the future, and an Office of the Chief Economist researcher found greater labour market flexibility is associated with lower unemployment, less so for older workers but more significantly for the young.[47] The Master Grocers, in a similar vein to some other industry bodies, argued:

“…measures contained within this Bill will increase the complexity, cost and administrative burden of Australia’s industrial relations system with no measurable increase to productivity, and further, act as an active disincentive to employ or engage workers in Australian businesses.”[48]

This is especially problematic given Australia already has a highly-regulated labour market, at least relative to the flexibility in the rest of the economy. Australia underperforms poorly in international comparisons of labour market flexibility.[49] For instance, despite ranking 8th-highest in economic freedom overall in 2021 according to the Fraser Institute, Australia could only manage 28th overall regarding the freedom associated with its labour market regulations.[50]

We rank even worse on important specific sub-indicators, coming in at 46th for ‘labour regulations and minimum wage’ and 95th for ‘flexible wage determination’.[51] Not only would additional labour market regulation be bad for productivity, but it could also contribute to additional unemployment, on top of the expected increase as the Australian economy slows down in response to rising interest rates as the Reserve Bank attempts to bring inflation down.

Worse still, the bill will delegate new regulatory powers to the Fair Work Commission (FWC), meaning that new rules made in furtherance of the objectives of the bill — which may substantially impact the economy — would not be subject to the normal regulatory assessment process.

Conclusions

The bill should not proceed unless the government can offer a better analysis convincingly demonstrating net community benefits. The government needs to:

(a) demonstrate what the exact problems are; and

(b) demonstrate how these particular measures will make things better, yielding a net benefit to society.

At a minimum, the bill should not proceed at this stage, given the grossly insufficient analysis in the Explanatory Memorandum (EM). There is a risk that, like the Fair Work Act 2009 and its 2022 amendments, the new laws could have adverse consequences, noting the e61 Institute research has revealed adverse impacts on productivity and employment in some firms.[52]

The e61 Institute has also raised the issue of potential adverse impacts from multi-enterprise bargaining;[53] as did the Productivity Commission, which is concerned the changes “could constrain productivity growth and hence the scope for enduring real wage rises over time.”[54]

Essentially, the government is mostly proposing to close opportunities rather than loopholes. It is presenting the bill as addressing loopholes, however the major targets of its bill are not loopholes, but instead logical arrangements that promote business efficiency, productivity, and employment. Critics could allege the government is undertaking these measures as a favour to its union donors, rather than for the wellbeing of the Australian people.

That said, it should be acknowledged that the government is grappling with some complex issues. Some issues raise questions about existing regulations and whether they can be improved. Certainly, there are legitimate concerns regarding the health and safety of gig-economy workers on our roads. These issues appear to be more of a concern for migrant workers who are more likely to use the gig economy as their primary source of income.[55] But it is unclear why this is an issue for the FWC rather than for state transport departments and the police.

This is a wide-ranging set of proposals with the potential to materially impact Australian households, in an adverse way on balance, given how many of us have come to enjoy the convenience of the gig economy.

References

ABC News (2023) Federal department responsible for workplace and employment conditions admits to underpaying staff, 26 October 2023, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-10-26/tony-burke-employment-department-staff-underpayment-fair-work/103024586

Actuaries Institute (2020) The Rise of the Gig Economy and its Impact on the Australian Workforce, Green Paper.

Andrews, Dan and Buckley, Jack (2023a) No free lunch: The economic consequences of job dismissal laws, e61 Institute Research Note no. 10.

Andrews, Dan and Buckley, Jack (2023b) Multi-employer bargaining and Firm Heterogeneity: a case study, e61 Institute Micro Note.

Australian Resources and Energy Employer Association (2023) Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes) Bill 2023: Submission To the Education And Employment Legislation Committee, October | 2023.

Business Council of Australia (2023) Fair Work Amendment (Closing Loopholes Bill) BCA Submission to the Senate Education And Employment Legislation Committee inquiry, September 2023.

Catholic Social Services Australia (2023) Submission to the Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes) Bill 2023 Inquiry.

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (2023a) Minimum standards and increased access to dispute resolution for independent contractors (OBPR22-02873) Annexure A – Supplementary Analysis to Impact Analysis Equivalent process, 23 August 2023.

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (2023b) Annexures to Certification Letter OBPR22-02409, Closing the labour hire loophole August 2023.

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (2023c), Standing up for casual workers (OBPR22-02412) Assessment that the Senate Select Committee on Job Security Inquiry and the Review of the Fair Work Amendment (Supporting Australia’s Jobs and Economic Recovery) Act 2021 (Cth) are equivalent to an impact assessment process.

Fair Work Commission (2023) Statistical report—Annual Wage Review 2022–23, Version 6, 18 May 2023.

Fraser Institute (2023), Data from Economic Freedom of the World: 2023 Annual Report. Copyright 2023.

Gottliebsen, Robert (2023) “Lack of certainty as to whether firms are obeying or breaking the law”, The Australian, 12 September 2023.

Hannan, Ewin (2023) “Business groups at war over IR reforms”, The Australian, 22 November 2023.

Holtum, Peter, Elnaz Irannezhad, Greg Marston, and Renuka Mahadevan (2021) “Business or Pleasure? A Comparison of Migrant and Non-Migrant Uber Drivers in Australia”, Work, Employment and Society 2022, Vol. 36(2) 290–309.

Jericho, Greg (2023) “It’s good news that real wages are no longer falling – but the fall has already been deep”, The Guardian, 17 August 2023.

Kent, Christopher and Simon, John (2007) “Productivity Growth: The Effect of Market Regulations”, Reserve Bank of Australia Research Discussion Paper, 2007-04.

Master Grocers Australia (2023) Submission to the Education and Employment Legislation Committee for Inquiry from Master Grocers Australia, Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes) Bill 2023, September 2023.

McManus, Sally (2023) “Parliament must listen to workers on IR, not corporate KCs”, Australian Financial Review, 29 October 2023.

Minister for Employment and Workplace Relations, the Hon Tony Burke MP (2023a) Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes) Bill 2023 Explanatory Memorandum.

Minister for Employment and Workplace Relations, the Hon Tony Burke MP (2023b) Q&A National Press Club Speech, Closing Loopholes Bill.

Mowbray, N, D Rozenbes, T Wheatley and K Yuen (2009) Changes in the Australian Labour Market over the Economic Cycle, Australian Fair Pay Commission.

Productivity Commission (2023) 5-year Productivity Inquiry – volume 7: A more productive labour market.

Rafi, Bilal (2017) “The impact of labour market regulation on the unemployment rate: Evidence from OECD economies”, Office of the Chief Economist, Research Paper 3/2017.

Safe Work Australia (2023) Decision Regulation Impact Statement: Prohibition on the use of engineered stone.

Sloan, Judith (2023) “Labor’s IR bill helps unions and punishes workers”, The Australian, 24 October 2023.

Sowell, T. (2008) Economic Facts and Fallacies, Basic Books.

Victorian Government (2020) Report of the Inquiry into the Victorian On-Demand Workforce.

Ziffer, D. (2023) “Gig economy shifts as Uber takes on supermarket delivery, government pushes for minimum employment standards”, ABC News, 25 April 2023, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-04-25/gig-economy-shift-as-uber-takes-on-supermarket-delivery/102234068

Endnotes

[1] https://www.claytonutz.com/knowledge/2022/december/secure-jobs-better-pay-your-guide-to-the-reforms

[2] Jericho, Greg (2023) “It’s good news that real wages are no longer falling – but the fall has already been deep”, The Guardian, 17 August 2023.

[3] McManus, Sally (2023) “Parliament must listen to workers on IR, not corporate KCs”, Australian Financial Review, 29 October 2023.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Alexander, David (2023) “Heavy-handed industrial relations intervention will choke productivity”, The Australian, 12 June 2023.

[6] Hannan, Ewen (2023) “Back off, Tony Burke: employers launch bid for a truce”, The Australian, 30 October 2023.

[7] Minister for Employment and Workplace Relations, the Hon Tony Burke MP (2023a) Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes) Bill 2023 Explanatory Memorandum, pp. 183-184.

[8] See the Catholic Social Services Australia (2023) Submission to the Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes) Bill 2023 Inquiry, p. 3.

[9] Minister for Employment and Workplace Relations, the Hon Tony Burke MP (2023b) Q&A National Press Club Speech, Closing Loopholes Bill, https://ministers.dewr.gov.au/burke/qa-national-press-club-speech-closing-loopholes-bill

[10] Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (2023a) Minimum standards and increased access to dispute resolution for independent contractors (OBPR22-02873) Annexure A – Supplementary Analysis to Impact Analysis Equivalent process, 23 August 2023, p.71.

[11] Ibid, p.67.

[12] Sowell, T. (2008) Economic Facts and Fallacies, Basic Books, p.3.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ziffer, D. (2023) “Gig economy shifts as Uber takes on supermarket delivery, government pushes for minimum employment standards”, ABC News, 25 April 2023, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-04-25/gig-economy-shift-as-uber-takes-on-supermarket-delivery/102234068

[15] https://labourmarketinsights.gov.au/occupation-profile/Delivery-Drivers?occupationCode=7321

[16] ABS Labour Force, Australia, cat. no. 6202.0.

[17] Victorian Government (2020) Report of the Inquiry into the Victorian On-Demand Workforce, p.14.

[18] Sloan (2023).

[19] https://www.actu.org.au/media-release/platform-workers-to-lose-110-million-due-to-closing-loopholes-bill-delay/

[20] Productivity Commission (2023, p. 175).

[21] Ibid, p. 133.

[22] Actuaries Institute (2020, p. 5).

[23] Ibid.

[24] The assumed -0.65 is the midpoint of a range of estimates reported on p. 11 of N Mowbray, D Rozenbes, T Wheatley and K Yuen (2009) Changes in the Australian Labour Market

over the Economic Cycle, Australian Fair Pay Commission.

[25] Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (2023b) Annexures to Certification Letter OBPR22-02409, Closing the labour hire loophole August 2023, p.45.

[26] ACCI (2023, pp. 7-8) and AREEA (2023, p. 3).

[27] AREEA (2023, p. 3).

[28] Hannan, Ewin (2023) “Business groups at war over IR reforms”, The Australian, 22 November 2023.

[29] AREEA (2023, p. 6)

[30] Ai Group (2023, p. 28).

[31] Regarding the current pathway, see https://www.fairwork.gov.au/starting-employment/types-of-employees/casual-employees/becoming-a-permanent-employee

[32] Commins, P. (2023) “Labor risks war with business over extra casual workers rights”, The Australian, 24 July 2023, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/labor-risks-war-with-business-over-extra-casual-workers-rights/news-story/daceb7385ab55faeca2159a9c50f7389

[33] Based on ABS Labour Force, Australia data reported in Fair Work Commission (2023, p. 112).

[34] Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (2023c), Standing up for casual workers (OBPR22-02412) Assessment that the Senate Select Committee on Job Security Inquiry and the Review of the Fair Work Amendment (Supporting Australia’s Jobs and Economic Recovery) Act 2021 (Cth) are equivalent to an impact assessment process, p. 7.

[35] Ibid, p. 11.

[36] BETA (2022) Casual Employment: Research findings to inform independent review of SAJER Act, p. 11.

[37] ACCI (2023, p. 7).

[38] Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (2023c), Standing up for casual workers (OBPR22-02412) Assessment that the Senate Select Committee on Job Security Inquiry and the Review of the Fair Work Amendment (Supporting Australia’s Jobs and Economic Recovery) Act 2021 (Cth) are equivalent to an impact assessment process, p.32.

[39] Ibid, p.28.

[40] Master Grocers Australia (2023, p. 11).

[41] ABC News (2023).

[42] Ai Group (2023, p. 104).

[43] Ibid. and BCA (2013, p. 23).

[44] Landers and Rogers (2023) Proposed laws to criminalise wage theft, https://www.landers.com.au/legal-insights-news/proposed-laws-to-criminalise-wage-theft

[45] Safe Work Australia (2023).

[46] BCA (2013, pp. 22-23).

[47] See Kent and Simon (2007, p. 1) and Rafi (2017, p. 1).

[48] Master Grocers of Australia (2023, p. 5).

[49] Rafi (2017, p. 9).

[50] Fraser Institute (2023), Data from Economic Freedom of the World: 2023 Annual Report.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Andrews, Dan and Buckley, Jack (2023a) No free lunch: The economic consequences of job dismissal laws, e61 Institute Research Note no. 10, p. 2.

[53] Andrews and Buckley (2023b, p. 1) noted “The widespread heterogeneity in firm performance within industries, however, raises questions about the capacity of lower performing firms to pay higher wages and the potential impact on market competition if they are drawn into the enterprise agreement of a higher performing firm.”

[54] Productivity Commission (2023) 5-year Productivity Inquiry – volume 7: A more productive labour market, p. 123.

[55] Holtum, Peter et al. (2021).