The Centre for Independent Studies welcomes the opportunity to respond to Transgrid’s Contingent Project Application Stage 2 (CPA2) application for HumeLink.

The CIS is a leading independent public policy think tank in Australia. It has been a strong advocate for free markets and limited government for more than 40 years. The CIS is independent and non-partisan in both its funding and research, does no commissioned research nor takes any government money to support its public policy work.

Our Energy Team has found that the CPA for Stage 2 for HumeLink is not a credible basis on which the ever-increasing costs of HumeLink should be approved and passed to consumers. The MCC assessment (MCCA) which underlies the CPA has astronomical benefits, and does not credibly show either that the net market benefit is positive, nor that Option 3C is still the best option.

Concerningly, we have also found that the process which has led to the CPA is not compliant with the NER, and relies on incorrect claims about the nature of the consultation process.

- We submit that the trigger event criteria have not been met, because the feedback loop was performed using an unconsulted ODP from the Draft 2024 ISP; violating the National Electricity Rules at the time of the request for the feedback loop.

- The AER had no right to waive the consultation requirement set out in the rules. Both the Glissan Opinion (attached) and the regulator’s own admission show that consultation is legally required, and that the AER had no discretion to waive it. Such discretion, the Glissan Opinion concludes, does not exist “other than in the mind of the regulator.”

- Representations from the AER on the nature of consultations being skipped were incorrect. The consultations that were skipped were neither duplicative, nor lesser than prior consultations.

- Transgrid’s decision to delay submitting the MCCA until after submitting the Stage 2 CPA contravenes the NER, as well as AER directives.[i] It undermines the RIT-T process and transparency expected in the evaluation of significant infrastructure projects like HumeLink. These significant problems mean the MCCA does not provide the “supporting information necessary to demonstrate that the preferred option identified remains the preferred option.”[ii]

- The increase in costs (nominally more than 50%, and well beyond the level of other infrastructure projects and outside of the accuracy ranges for the PADR and PACR) is reason to exercise the flexibility that was the explicit purpose of staging. Indeed, Transgrid cites the Infrastructure Australia report that shows public infrastructure projects that can be deferred, should be; both to reduce the costs of the project and to ease the pressure on Australia’s public infrastructure.

- Finally, The CPA relies on an MCCA that does not credibly model the benefits of the HumeLink project. It finds a nearly 7.7x increase in net economic benefits since the PACR, and 3.4x more than the contemporary assessment in the 2024 Draft ISP. Explanations for this significant increase are insufficient, as shown in our submission to the MCCA .

[i] AER, Advice to Transgrid in relation to material change in circumstances provisions, letter dated 22 August 2023.

[ii] NER v207, 5.16A.4(o2)(1).

This CPA is invalid because the feedback loop was applied on an improperly updated ISP

We submit that the trigger event criteria in 5.16A.5 have not been met, because the feedback loop was performed using an unconsulted Optimal Development Path (ODP) from the Draft 2024 ISP; violating the National Electricity Rules (NER) at the time of the request for the feedback loop.

The feedback loop therefore needs to be performed again before the AER can approve this Contingent Project Application. Either it should be performed against the 2022 ISP, properly updated as per 5.22.15(c), or else performed against the Final 2024 ISP. We note that this could make a material difference to the outcome of the feedback loop: the net benefits of HumeLink in the 2022 ISP are now clearly exceeded by the escalated costs and there would be no reason to immediately advance HumeLink Stage 2.

The contention that the trigger event has not been met is advanced through seven propositions detailed in the sections below.

1. The NER as of 22 December 2023 apply to HumeLink

NER Version 207 and following do not apply to HumeLink because Transgrid lodged the feedback loop request on 22 December 2023 — before the rule change came into effect on 14 March 2024 — and because the rule change did not apply retrospectively.

This is clear in both the rules and the rule change itself. Clause 11.164.2 of the NER states that rule 5.16A continues to apply:

11.164.2 Existing actionable ISP projects prior to the clause 5.16A.5 stage

(a) This clause 11.164.2 applies if, at the commencement date, for an existing actionable ISP project (or a stage of an actionable ISP project if the actionable ISP project is a staged project) the RIT-T proponent has requested written confirmation from AEMO under clause 5.16A.5(b).

(b) For an existing actionable ISP project (or a stage of an actionable ISP project if the actionable ISP project is a staged project) referred to in paragraph (a), rule 5.16A continues to apply as if the Amending Rule had not been made.[1]

The AEMC is also clear in its “Improving the workability of the feedback loop” amendment that the rule change should not apply to such a project:

The Commission considers that if a feedback loop request for an actionable ISP project (or stage of an actionable ISP project) is made prior to the commencement of the rule, the existing NER framework would apply.[2]

2. A ‘trigger event’ is required for this CPA to be valid

According to the NER 6A.8.A1(b), eligibility for consideration as a contingent project requires a ‘trigger event’. Without the trigger event, this project is not eligible as a contingent project.

3. The ‘trigger event’ did not occur because the ‘feedback loop’ was invalid

One of the criteria for a ‘trigger event’ under the NER is that:

-

- Transgrid obtains written confirmation from AEMO that HumeLink (the “preferred option”) aligns with the “most recent Integrated System Plan” and that:

- The cost of the preferred option does not change the status of the actionable ISP project (i.e. HumeLink) as part of the optimal development path as updated in accordance with clause 5.22.15 where applicable.[3]

These criteria were not satisfied, because HumeLink was only found to align with an ISP which was not updated in accordance with clause 5.22.15. Consequently, the feedback loop confirmation was invalid.

4. The feedback loop was invalid because it did not refer to the ODP in the latest properly updated ISP

The ‘feedback loop’ used the Draft 2024 ISP, because AEMO issued an update six days prior on the 15 December 2023, which nominally updated the ISP from the 2022 ISP to the Draft 2024 ISP. However, this update was invalid for the purposes of the feedback loop because it did not satisfy clause 5.22.15 of the NER. Specifically, 5.22.15(c) of NER v204 requires that:

If AEMO is required to publish an ISP update … AEMO must consult on the new information and the impact on the optimal development path under the Integrated System Plan, in accordance with the consultation requirements set out in the Forecasting Best Practice Guidelines for an ISP update.

The Draft 2024 ISP was released on the same day AEMO issued the update to the ISP and the ODP on 15 December 2023. This updated the ODP without consultation on the ODP. This violated the NER, and invalidates the ‘feedback loop’ confirmation issued on the basis of the update.

5. The AER had no right to waive the consultation requirement set out in the rules

During the hearing of the Senate Environment and Communications Legislation Committee on 12 February 2024, AER Chair, Ms Clare Savage, was challenged about AER’s failure to enforce NER Rule 5.22.15(c) by waiving AEMO’s obligation to consult on new information and its impact on the ODP under the ISP in accordance with the consultation requirements set out in the Forecasting Best Practice Guidelines for an ISP update.

In response, the AER Chair asserted before the Senate committee that the consultation requirements for an ISP update are not as comprehensive as those for an ISP itself.[4] Moreover, she argued that the extensive consultation process already completed for the Draft 2024 ISP exceeded what would have typically been required for an ISP update, and that it would have been duplicative to go through the consultation process again.[5]

The AER Chair asserted in this context that the AER was invested with a discretion such that “it is within our right to do that [i.e. waiving the mandated consultation] under the law, and it is our guidelines that they would be needing to comply with.”[6]

The two assertions made multiple times by the AER Chair before the Senate hearing — that the skipped consultation was ‘duplicative’, and that the AER has the legal right to skip consultations because they are ‘guidelines’ and not rules — are incorrect. As James Glissan AM ESM KC states in his Memorandum of Opinion (the Glissan Opinion):

While the NER permits AER to specify those parts of the guidelines binding on AEMO, this is not on an ad hoc basis, but as set forth in the guidelines themselves and in precise detail. No discretion to waive compliance is contemplated in those parts of the FBPG that have been declared to be binding requirements or binding considerations… No discretion for AER to forgive such a breach can be found in the legislation — no rule is formulated to supersede the duty imposed on AER which was to enforce compliance by AEMO with the FBPG… it is clear that no discretion to waive this precise consultative process required to be undertaken by AEMO is afforded AER by the legislation or the FBPG. The duty of AER is to ensure that the Rules have been complied with both in spirit and in the letter of the law.[7] (emphasis added)

In fact, according to the AER Chair’s own signed letter to AEMO on 4 October 2021, the waiver was considered a skip in the requirements “set out in the NER”:

The AER notes AEMO’s position to not undertake consultation to issue an ISP Update in the manner outlined above and, in accordance with the consultation requirements set out in the NER and AER’s FBPG.[8]

By the Glissan Opinion, and by the regulator’s own admission, it is apparent that the consultation process is legally required, and that the AER — prior to the rule change — had no discretion to waive such process. Such discretion, the Glissan Opinion concludes, is not to be found in the legislative instruments and does not exist “other than in the mind of the regulator.”[9]

6. The regulator’s representations of the skipped consultations were incorrect.

The ‘duplicative consultation’ argument was made in the formal correspondence between the Regulator and AEMO in 2021:

… there is likely to be limited value in undertaking a separate consultation process for the purposes of the ISP Update considering the recently completed consultation undertaken during the development of 2021 IASR and the ISP methodology.[10]

This argument has been relied upon again in the current process. The regulator repeatedly told the Senate hearing that the consultation processes were duplicative, and that the consultation process already completed for the Draft 2024 ISP exceeded what would have typically been required for an ISP update.[11] [12]

Examining the elements each process consults on reveals that argument is incorrect. A Draft ODP is not consulted on during the development of an IASR or an ISP methodology, and is only revealed in a Draft ISP. The Draft 2024 ISP had not undergone consultation at the time the feedback loop notice was published. Therefore, the Draft ODP had not been consulted on.

Merely allowing consultation on the inputs, assumptions, scenarios and methodology to be used to greenlight a project — without allowing consultation on the final actionable project outputs — is akin to judging a cooking competition based on the ingredients and recipe instead of the resultant dish. Consultation on inputs is not a substitute for consultation on outputs.

Consequently, the ‘duplicative consultation’ argument is incorrect and is not justification for skipping the most important part of the consultation process (i.e., completing consultation on the Draft ODP prior to the feedback loop process greenlighting the project).

Further, the AER Chair cannot reasonably claim to be unaware that consultation on the outputs of the ISP (the Optimal Development Path) was required by the relevant rules, when making this argument before Senate Estimates. At the commencement of questioning, the very rule in question was read to her, including the explicit reference to the impact on the Optimal Development Path, and she replied: “I am aware of that, thank you.”

The regulator’s reliance on such a flawed argument to dismiss a rule violation is concerning. The regulator has failed to protect consumers by preventing consumer input from being capable of changing the final outcome of project approvals in the most crucial stage. This has resulted in the project being rushed through, and will cost consumers billions of dollars through their energy bills without the confidence of knowing the rules have been followed and the correct processes applied, which are supposed to protect their long-term interests.

7. Until properly updated, the 2022 ISP remains the legitimate benchmark for assessing HumeLink

We therefore submit that the update to the 2022 ISP is not lawful and that Transgrid should have either used the 2022 ISP, waited for the Final 2024 ISP, or completed the consultation required under NER 5.22.15(c) for an update. Until the Final ISP is released, or a legitimate update occurs, the 2022 ISP remains as the legitimate benchmark against which HumeLink must be assessed.

The CPA is non-compliant because Transgrid did not comply with the NER nor satisfy AER requests

Transgrid’s decision to delay the MCCA until after submitting the Stage 2 CPA contravenes NER 5.16A.4(t) which was in place at the time the CPA was lodged. The delayed MCCA also contravenes the AER directives regarding NER 5.16A.4(n).[13] Such action undermines the RIT-T process and transparency expected in the evaluation of significant infrastructure projects like HumeLink.

Transgrid’s failure in complying with the NER and AER’s written request to promptly publish a MCCA, whether intentional or not, has the effect of ensuring that:

- Market benefits could be maximised by using the amended 2023 IASR inputs published alongside the Draft 2024 ISP; particularly the 660 MW constraint on Snowy Hydro in the absence of HumeLink and new 2200 MW rated power.

- Stakeholders were left effectively unaware of the possibility of a material change being assessed as a consequence of the cost increases. This was exacerbated by the regulator’s decision not to publish the CPA as soon as practicable following its submission, as required by NER 6A8.2(c), despite the CPA being foreshadowed to be lodged immediately on receipt of the Feedback Loop.

- There is now no credible way in which feedback from the MCCA could be incorporated into the CPA, which has already been lodged. This severely undermines the credibility of the consultation process.

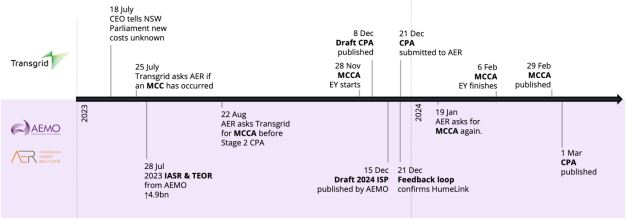

Figure 1. Timeline of events surrounding the MCCA

Transgrid’s CEO previously testified before the NSW Parliamentary Committee on 18 July 2023 that the cost of HumeLink has increased by around 30%, while confirming a nominal dollar figure that would be closer to 50%.[14] A week later, on 25 July, Transgrid wrote to AER asking if Transgrid needs to assess if a ‘material change in circumstances’ occurred in light of the cost escalation, as mentioned in AER’s correspondence to Transgrid. We note that Transgrid’s inquiry is not publicly available; we request that the AER make their inquiry available to the public.

AER responded to Transgrid’s inquiry, confirming that they should do so promptly:

Transgrid should determine whether there has been a material change in circumstances as soon as possible. We consider it necessary that Transgrid make the ‘material change in circumstances’ assessment available to the AER and stakeholders, before it submits a further contingent project application to the AER.[15] (emphasis added)

Despite this, Transgrid completed their MCCA on 29 February 2024, nearly six months later. In addition, they submitted their Stage 2 CPA on 21 December 2023, 70 days prior to completing the MCCA; directly contradicting AER’s directive that the NER required Transgrid to supply evidence of the MCCA prior to a CPA. This led AER to issue another notice to Transgrid on 19 January 2024, warning that the CPA is at risk of being non-compliant for not lodging the MCCA before submitting the Stage 2 application.[16]

In the August 2023 Determination, the AER stated: “it is our expectation that Transgrid will more consistently, transparently and meaningfully engage with its stakeholders and the wider community for the remainder of the HumeLink project.”[17] We believe Transgrid’s delay in complying with the NER ultimately diminishes the opportunities for meaningful consultation and fails to reach this standard.

In the present circumstance, there appears to be no opportunity for the CPA to be modified in response to feedback from the MCCA, and also no practical opportunity for stakeholders to consider and respond to any responses to issues raised in consultation prior to the close of submissions on the CPA.

Transgrid’s failure to comply with the NER or satisfy AER’s directives to submit the MCCA prior to the CPA is another basis for questioning the validity of the current CPA.

Questionable revision of HumeLink’s capital expenditure estimates

We question the reliability of the revised capital expenditure estimates for HumeLink, and suggest they require further examination. This concern is raised in our submission to Transgrid’s MCCA. Specifically, the relatively modest increase in the projected costs for HumeLink (Option 3C) of 28% since the PACR Addendum, in contrast with to the 39% and 44% increases for Options 1C-new and 2C respectively. The reasons given for the additional premium increases for the other options fail to consider cost reductions from early works that might transfer between options, and make the blanket assumption that delaying the project leads to higher future real costs. This conflicts with evidence that delaying infrastructure to ease constrained labour and material supply can reduce future costs, as discussed below, and biases the costings against alternative options.

Nominal HumeLink costs increased more than 50% and justify deferral

The increase in costs (nominally more than 50%) is well beyond the level of other infrastructure projects and outside of the accuracy ranges for the PADR and PACR, thus is reason to exercise the flexibility that was the explicit purpose of staging.

The CPA incorrectly asserts that a real cost increases of 30 percent “is in line with the overall cost increase of around 30 per cent for energy infrastructure projects across all elements of the supply chain over the last two years.” The Infrastructure Australia report cited by Transgrid states that costs for materials increased in nominally by 24%, and labour costs increased nominally by only 14%. A like-for-like comparison against the nominal increase in costs seen by the HumeLink project of 50.4% shows that it has increased well beyond inflation.

The same report from Infrastructure Australia shows that inflation is being driven by rushing public infrastructure projects, and disregarding nationwide benefits that would be accrued by deferring key infrastructure projects until workforce and material shortages have subsided. HumeLink is a key candidate for this kind of deferral because the optimal delivery date in the ISP is not 2026, but 2029, and because it was staged precisely to allow it to be deferred in the case of cost blowouts.

AER’s HumeLink Stage 1 CPA determination states:

“the benefits to consumers of Transgrid undertaking early works are … option value to retain flexibility to proceed with the project only if it remains the preferred option once the full project costs are known.”[18]

AEMO’s ISP Feedback Loop Notice for HumeLink (Early Works) defined the early works as:

“Pre-construction activities that can be taken now, while keeping open the option to either continue, defer, or cancel the project as new information becomes available.”[19]

Indeed, the project has easily breached the accuracy thresholds specified in previous stages of the RIT-T process. The PACR had accuracy ranges of -30% to +50% which have been far exceeded by the CPA estimate of $4.92 billion; well above the +50% upper limit of PADR ($1.5 billion) and above the upper limit of the PACR.

The CPA relies on an MCCA that does not credibly model benefits

The MCCA this CPA is contingent upon does not credibly model gross market benefits, as it should, in order to justify both continuing with ‘Reinforcing the NSW Southern Shared Network’, and continuing with Option 3C (i.e. HumeLink) in particular.

We submit that the AER should reject the CPA for two reasons relating to the MCCA:

- The MCCA was provided following submission of the CPA.

- The cost-benefit analysis underpinning the MCCA is unsatisfactory, and does not adequately demonstrate that an MCC has not occurred.

Below we included relevant sections from our submission to Transgrid’s MCCA consultation process. These sections provide detailed arguments for why the model used in the MCC is not credible.

An outline of the arguments made there are:

- The 7.7x increase in net economic benefits since the PACR and 3.4x increase since the Draft 2024 ISP demand a detailed and transparent explanation of the increase in Transgrid’s projection of HumeLink’s market benefits. The MCC currently fails to do this.

- The MCC model provided by EY differs in key ways from that used by the ISP. This makes it impossible to assess the actual cause of the sudden change in benefits, and damages the credibility of any economic assessment, and also greatly contradicts argument used to justify using the same inputs as the 2024 Draft ISP.

- The MCC models implausibly large benefits from avoided USE/DSP in the Progressive Change scenario, which is an unrealistic source of benefits (because those hypothetical costs would not be incurred in the real world), and shows the illogicality of the weather assumptions in the model.

- The provided costings are biased in favour of HumeLink and against alternatives. This is particularly shown by the disproportionate increase in the costs of other similar options to Option 3C such as Option 1C-new.

- As argued above, Transgrid failed to comply with both the NER and explicit, early AER requests to comply with the NER.

Opaque and inconsistent market benefits modelling

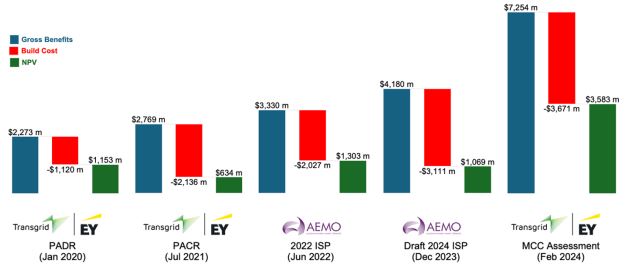

The total cost for delivering HumeLink, as disclosed by Transgrid, escalated from $3.3 billion (June 2021 dollars) to $4.88b (June 2023 dollars), marking a $1.15b increase (or +31%) in June 2023 dollar terms since the publication of the PACR Addendum in December 2021.[20] Given that the net present value (NPV) of HumeLink in the Step Change scenario was $408 million (June 2023 dollars),[21] a $1.15b increase in real costs would presumably make HumeLink’s NPV negative and result in a material change in circumstances.

The 7.7x increase in NPV to $3.58b under Transgrid’s revised estimates is therefore a shock. It is also more than triple the $1.07b NPV estimated by AEMO in the Draft 2024 ISP via the ‘TOOT’ analysis.[22] As EY notes in their Gross Market Benefit Assessment of Humelink, the significant difference in net economic benefits cannot simply be attributed to “the three-year difference in commissioning date and outlook period”[23] from the Draft 2024 ISP.

Figure 2. Successive changes in HumeLink’s Step Change scenario NPV[24]

EY’s Gross Market Benefit Assessment of HumeLink estimates a total discounted market benefit of $7.25b, 74% more than the Draft 2024 ISP, and 161% more than the same model in the PACR. This significant change brings into question the reliability of the entire assessment.

EY provides a number of reasons for the difference between the gross market benefit outcome of their model and the outcome in the Draft 2024 ISP:

- EY’s reason: The model in MCCA includes more network detail in Southern New South Wales, capturing key transmission limits and losses, facilitating a direct comparison to the HumeLink RIT-T assessment.

- Our response: While additional detail is appropriate for distinguishing between options, assuming that the ISP’s simplifying assumptions are reasonable, it should not contribute significantly to gross market benefits nearly doubling. If it does, it brings the assumptions of the ISP or the EY model into significant question.

- EY’s reason: Different assumptions regarding the timing of transmission projects between the TOOT analysis and MCCA, affecting commissioning dates for several key projects like the Central West Orana and New England REZ Transmission Links, Project Marinus, and VNI West.

- Our response: While these differences have been transparently listed, the report fails to justify why they should be changed; given the requirement to align as closely as possible to the ISP parameters, which are defined as including “other ISP projects associated with the optimal development path”.[25] Either these changes should be so minor as to not affect the outcomes, or so significant as to warrant a clear explanation of why they are required.

- EY’s reason: Variations in the treatment of REZ transmission upgrades, particularly for the South-West NSW and Wagga Wagga REZs, where the TOOT analysis and the MCCA diverge in assumptions about transmission build associated with HumeLink.

- Our response: The freedom for the model to adjust, expand, reduce or remove other transmission projects is a significant degree of freedom for the model. Given the requirement for RIT-T proponents to adopt ISP parameters, including other ISP projects, it is clear this divergence in method is not justified.

- EY’s reason: Structural differences in the modelling approach, with the MCCA computing an hourly build and dispatch solution for generation, storage, and transmission as a single solution, in contrast with the ISP’s multi-stage approach.

- Our response: Structural differences seem most likely to account for the huge increases in the gross market benefits, yet they are neither explained nor justified as appropriate divergences from ISP modelling. In particular, the treatment of contingency reserves — and the degree to which these are effectively ‘hard’ constraints or priced to penalise breaches, and whether storage contributes to reserves — significantly impacts the degree to which the model might become ‘overfit’ due to the perfect-foresight modelling. Failure to align this modelling behaviour with that of the ISP makes it impossible to draw any conclusions about a comparative cost-benefit analysis.

We consider the reasons EY offered above insufficient to justify the size of the change in gross market benefit, and insufficient to justify the divergence from the ISP parameters and modelling.

Finally, EY modelling produces implausibly large benefits from avoided unserved energy or demand side participation (USE/DSP) during 2029/30 in the Progressive Change scenario, and to a lesser extent the Step Change Scenario. EY notes that these benefits are the result of essentially forcing alternative thermal generation not to run in the counterfactual, as running it would result in “not meeting the renewable energy policy targets, leaving a gap in supply.”

This is an implausible outcome, which is inappropriate for use in a cost-benefit analysis on which decisions are being made. Power outages of this scale would not be permitted as a result of forced shutdown of viable energy generation. Multiple political leaders, including Energy Minister Chris Bowen, have made public commitments to not withdraw generation earlier than would maintain reliable electricity. Applying hard constraints to the energy system based on policy targets is unrealistic and confers artificial benefits to a project such as this one.

This outcome also shows the illogicality of the weather assumptions in the model. Bad weather years cannot be predicted, and yet around $750 million of NPV is derived from a single bad weather year being fed into the model just after HumeLink is finished and Snowy Hydro 2.0 comes online to make use of the increased capacity. Page 24 of the Gross Market Benefits Assessment outlines that weather is driving this: “DSP dispatch occurs as it is determined that it is cheaper than to build additional wind, solar or storage capacity that isn’t heavily utilised in other weather years when renewable energy has higher availability.”

Overall, the massive escalation in benefits in an opaque model is not justified, and brings into question the reliability of the model and the assumptions used to make a critical decision that will significantly affect the future of the NEM and its costs to consumers.

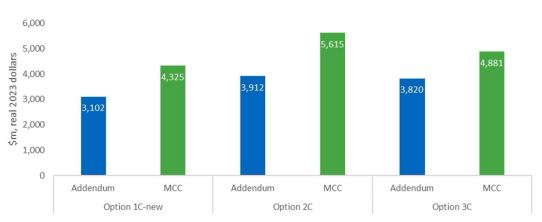

Bias towards currently preferred option against alternatives

The capital expenditure costs for Option 1C-new and Option 2C have both seen a significant increase since the PACR — 39% ($1,223 million) and 44% ($1,703 million) respectively — whereas the cost for Option 3C has risen by a lesser extent: only 28% ($1,061 million). Given that Option 3C includes everything from Option 1C-new plus the additional stretch from Wondalga to Wagga Wagga, it raises questions as to why its cost increase is $162 million lower than that of Option 1C-new.

A large number of the reasons raised for the increase in cost for the preferred option include universal drivers that would affect any version of the project equally; such as constrained global supply lines and a tight labour market.

The reasons advanced that distinguish the alternative options all essentially amount to risks being retired through the effect of the early works for the preferred option; including by having engaged contractors already, or refined the path in order to reduce biodiversity costs. There doesn’t appear to be any serious effort to quantify the extent to which risks and costs retired by work on one option would actually be transferrable to another.

For instance, a route that is refined for the preferred option, reducing biodiversity costs, might have significant route overlap with an alternative system choice, which would reduce the biodiversity costs of this option also. This would also reduce the costs of additional community engagement for this option.

The effect of treatment of all these costs in this way is that any change to an alternative option is essentially precluded by virtue of it being a change. The assumption that all costs will rise in the future, rather than easing as supply chains and labour markets adapt, effectively locks in the currently preferred option. Without any serious attempt to assess the probable reduction in costs that early works may cause for other option, this makes the question of an MCC something close to a foregone conclusion.

Figure 3. Revised MCC capex cost estimates for the three options compared to the cost estimates in the PACR Addendum

[1] NER v207, p.1791

[2] AEMC, National Electricity Amendment (Improving the workability of the feedback loop) Rule 2024, p. 23, 7 March 2024.

[3] NER v204, 5.16A.5(b).

[4] Commonwealth of Australia, Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Senate Estimates, p 102, 12 February 2024.

[5] Commonwealth of Australia, Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Senate Estimates, p 107, 12 February 2024.

[6] Commonwealth of Australia, Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Senate Estimates, p 101, 12 February 2024.

[7] James Glissan, Memorandum of Opinion, p. 11, 27 February 2024.

[8] Clare Savage, letter to Daniel Westerman dated 4 October 2021, obtained through FOI request.

[9] James Glissan, Memorandum of Opinion, p. 11, 27 February 2024.

[10] Clare Savage, letter to Daniel Westerman dated 4 October 2021, obtained through FOI request.

[11] Commonwealth of Australia, Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Senate Estimates, p 102, 12 February 2024.

[12] Commonwealth of Australia, Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Senate Estimates, p 107, 12 February 2024.

[13] AER, Advice to Transgrid in relation to material change in circumstances provisions, letter dated 22 August 2023.

[14] Feasibility of undergrounding the transmission infrastructure for renewable energy projects, NSW Parliament, 18 July 2023.

[15] AER, Advice to Transgrid in relation to material change in circumstances provisions, letter dated 22 August 2023.

[16] AER, RE: Notice under clause 6A.8.2(h1) of the National Electricity Rules, letter to Transgrid dated 19 January 2024.

[17] AER, AER Determination: HumeLink Early Works Contingent Project, August 2023, p vi.

[18] AER, AER Determination: HumeLink Early Works Contingent Project, August 2023, p vi.

[19] AEMO, Integrated System Plan Feedback Loop Notice – HumeLink (Early Works), January 2022, p1.

[20] We note that the cited figure of “$3.27 billion (June 2021 dollars) assumed for Option 3C at the time of the PACR Addendum” in the MCCA is incongruent with the $3.3 billion reported on page 2 in the PACR Addendum. Accordingly, the MCCA’s estimate of a “cost increase of $1.06 billion” is understated. We further note that the 1.17 escalation factor adopted by Transgrid differs from the 12.5% increase in Australia CPI between June 2021 and June 2023; see footnote 2 below.

[21] Derived by discounting the project’s forecasted cash flows, as detailed in the PACR Addendum, in real 2021 dollars at a 7% discount rate. The figure was then adjusted to real 2022/23 dollars using the Australia CPI (ABS Series ID A2325846C). This inflation adjustment mirrors the method utilised in the PACR to adjust inputs to real 2020/21 dollars.

[22] Draft 2024 ISP, Appendix 6: Cost Benefit Analysis, p 41.

[23] Gross market benefit assessment of HumeLink report, February 2024, p 33.

[24] PADR reported in June 2019 dollars. PACR and 2022 ISP reported in June 2021 dollars. Draft 2024 ISP and MCC assessment reported in June 2023 dollars.

[25] NER 5.10.2