Home » Commentary » Opinion » Early numeracy screening will help prevent students from falling behind in maths

· ABC.NET.AU

Policymakers are on the verge of a major education reform — early numeracy screening — that will prevent children falling behind in their mathematical learning.

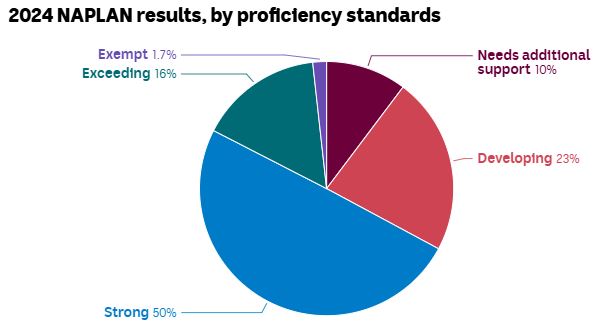

NAPLAN data confirms that one in three students lack proficiency in numeracy at Year 3.

Over recent weeks, the NSW and federal governments have promoted new numeracy screening for children in Year 1.

NSW Education Minister Prue Car has championed the cause and is actively considering policy solutions, while federal Education Minister Jason Clare has mandated early literacy and numeracy screening as a condition for $16 billion in funding.

This screening would help teachers to identify kids struggling early so that targeted support can be provided.

Policy leadership on this will, in time, mean schools are better equipped to provide the early identification and intervention that many students need.

The unfortunate truth is that schools are generally failing on this count. Too often, early difficulties with maths become entrenched problems that persist right throughout schooling.

Analysis of NAPLAN data shows that out of every five Year 3 children who fall behind, four will never go on to be proficient.

While many children struggle with maths from time to time — and can be supported through general classroom instruction — some difficulties can be an early warning sign for ongoing challenges. Good screening tools help teachers to see the difference.

Australia successfully implements national programs for the early detection of various types of cancer for adults. Newborn babies are screened for hearing problems and serious illnesses. The need to screen is equally important in education — particularly given how closely risk factors in literacy and numeracy predict later socio-economic and welfare outcomes.

In reading, universal screening is becoming common practice. The Year 1 Phonics Check — now in use across most Australian states — identifies Year 1 students who are struggling with early reading by zeroing in on an essential reading skill related to decoding the letters and letter patterns in words.

Where phonics screening is used widely, it results in steady improvement in literacy achievement. For numeracy screening, students might be asked to match numerals to dots, judge which of two numbers is more or solve some small number combinations.

Universal screening in education is key to greater success in the long term — just as it is in addressing health conditions early, allowing for timely intervention or treatment that can prevent complications and improve outcomes.

Effective screening would ensure that follow-up support — like the ‘catch-up tutoring’ initiative forecast by federal minister Clare — can be offered earlier when the achievement gap is much smaller.

Although universal screening is standard in health, it’s not as common in education. This is largely due to three misconceptions.

First, some think extensive school testing makes additional screening unnecessary.

Schools collect a lot of data through standardised tests like NAPLAN and classroom assessments to track achievement against curriculum goals. They also use diagnostic assessments, such as one-on-one interviews, to understand students’ current mathematical thinking and guide teaching.

However, screening has a different purpose. It aims to identify children who might face future challenges. This helps teachers, at an early stage, address potential barriers to progress.

Second, some claim brief screening checks are not holistic enough to be useful.

It’s true screening checks are less detailed than other assessment types, but this is by design.

By focusing only on key skills that are crucial for learning progress, educators can intervene early in areas that significantly impact a student’s overall academic performance.

This targeted approach can prevent small issues from becoming larger problems.

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority

Third, some critics are uncomfortable with any form of academic assessment for young children.

They cite concerns that testing is inappropriate in a time of such rapid development, and can cause anxiety.

Yes, children learn at different rates. But it doesn’t follow that we should be comfortable in condemning some of them to more than 10 years of struggling in school.

Concerns that testing might cause anxiety are understandable but don’t apply to screening.

Screening costs little in time and effort but has the capacity to have huge benefits in the form of school success and longer-term life outcomes.

Getting screening right in Australian schools is the best bet in securing the educational safety net our schools need. Top marks go to the education ministers on leading policy debate.

Kelly Norris and Glenn Fahey are senior research associate and program director in education policy at the Centre for Independent Studies. Kelly Norris is the author of the report Screening that counts: Why Australia needs universal early numeracy screening.

Photo by Yan Krukau.

Early numeracy screening will help prevent students from falling behind in maths