Home » Commentary » Opinion » The cost of nuclear: some clarifications

· NEWS WEEKLY

With the federal election looming, the already heated debate over Australia’s energy future is set to intensify. Last month, the Coalition released its modelling by Frontier Economics, purporting to show that its nuclear plan is cheaper than Labor’s renewables plan. Energy Minister Chris Bowen labelled the modelling as “dead before arrival”, claiming both the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) and CSIRO have confirmed nuclear energy is expensive.

Each side has its preferred experts. The fact that their models don’t agree highlights the importance of looking at the facts – including international experience – rather than relying on appeals to authority.

Labor relies on the CSIRO’s GenCost and AEMO’s Integrated System Plan (ISP) to claim their plan is cheaper. The Coalition relies on Frontier Economics’ model to claim theirs is cheaper. Both parties’ energy models are seriously flawed. But when we fix those flaws, nuclear comes out cheaper than renewables.

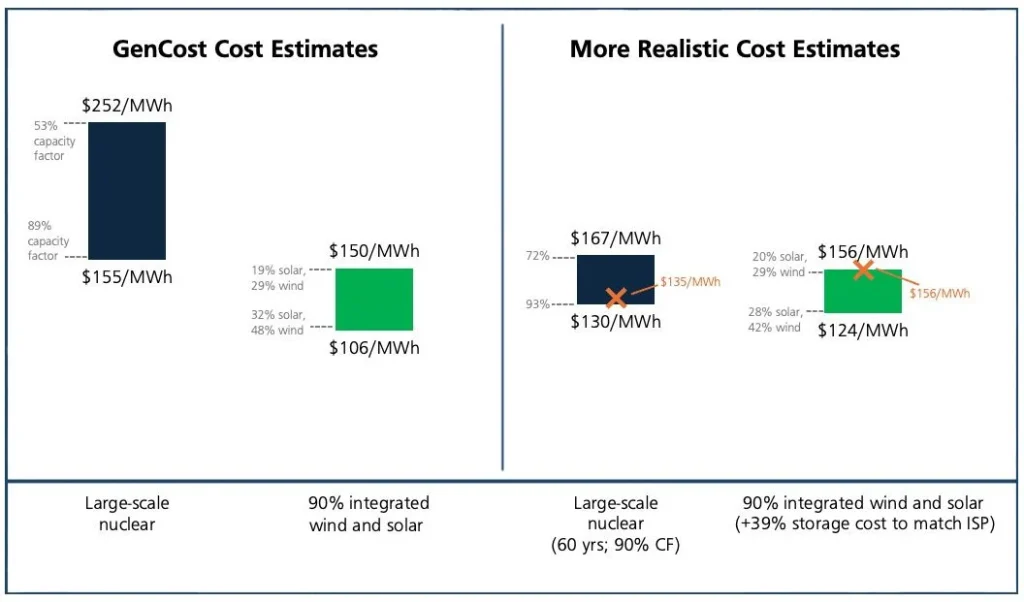

This is illustrated most clearly by looking into the assumptions underpinning the GenCost model. To conclude renewables are cheaper than nuclear, it relies on unrealistic assumptions about nuclear’s economic life and capacity factor as well as renewables’ storage, system stability, transmission, spillage and generation costs.

Let’s start with the nuclear assumptions.

GenCost assumes an economic life of 30 years for nuclear plants in their core analysis, despite modern plants lasting for 60 years or more. In response to criticism, the CSIRO analysed the effect of using a 60-year period in their latest draft, which reduced nuclear costs by 11%, or 9% with refurbishments. Wind and solar showed a similar cost reduction of 7% over the same period. This is because the authors assumed capital costs will dramatically fall over time, making future replacements cheaper.

But the CSIRO neglected to include the substantial cost of replacing storage over a 60-year period, invalidating the results of their case study. The flawed assumptions in their core analysis remain.

The CSIRO has also been criticised for its unrealistically low nuclear capacity factors. GenCost gives nuclear a wide range of 53-89% – which would mean paying billions to build a plant that reliably provides electricity, only to switch it off half the time to make room for weather-dependent renewables. If Australia builds nuclear plants, we should use them as much as possible – emulating the US fleet, which has an average capacity factor of 93%.

The GenCost report is internally inconsistent on nuclear capacity factors. The authors admit brown coal is almost always on, achieving a 90% capacity factor, because its low fuel cost allows it to underbid other generators. But according to the CSIRO, nuclear fuel will be even cheaper than brown coal in coming decades, so the same logic should apply.

Now let’s look at the renewables assumptions, which are far more opaque.

Checking the CSIRO’s renewables homework is difficult because the GenCost authors have refused to release all the detail – as Chief Economist Paul Graham stated in a recent webinar, they do not want to release modelling that would compete with AEMO’s full system model, the ISP. The irony is that though the CSIRO claims to use the ISP as its benchmark, GenCost’s poor attempts at modelling full system costs for renewables are far more optimistic than the costs indicated by the ISP.

First, GenCost estimates storage for a 90% renewables grid would cost around $18/MWh – a serious underestimate. The ISP indicates that achieving at least 90% wind and solar requires storage costs of $25/MWh; 40% more than the CSIRO claim.

Second, GenCost appears to underestimate system stability costs. As more wind and solar is added and dispatchable generation retired, synchronous condensers are increasingly needed to smooth out fluctuations in supply. But the CSIRO claims synchronous condenser costs will be near-zero for a 90% renewables grid, stating that gas generators will be able to maintain system stability, alongside hydro. The CSIRO has not revealed how much gas capacity it assumes will be generating, so it is unclear whether it would be enough to maintain system stability in this scenario.

Third, GenCost claims transmission would cost $23/MWh. High penetrations of renewables require the construction of more and more transmission lines to carry electricity from far-flung Renewable Energy Zones. The government’s plan also includes a massive rollout of state interconnectors, theoretically allowing one state to power another with renewables. But transmission projects are notorious for cost blowouts. As shown in Frontier Economics’ first report, almost all major projects listed in the 2020 ISP faced substantial cost estimate increases of 100% to 500% by 2024. Without knowing which projects GenCost has included, it’s difficult to know whether these cost blowouts have been accounted for.

Fourth, the CSIRO’s latest cost estimate for spillage – wasted energy from overbuilding solar and wind to increase minimum generation levels – is unclear. GenCost’s graph indicates spillage in a 90% renewables grid is around $4/MWh – but the report text claims spillage is more than $8/MWh. Mistakes like these make it difficult to rely on the CSIRO’s numbers, especially when the modelling has been largely kept from the public eye. But assuming $4/MWh is correct, GenCost’s spillage cost estimate is only 5% of generation. When renewables hit 90% penetration in the ISP, spillage costs are closer to 12% of generation – more than double the GenCost estimate.

Finally, GenCost underestimates generation costs for wind and solar. Just as the CSIRO gave nuclear an unrealistically low range of capacity factors, GenCost gives renewables an unrealistically high range – making renewables look cheaper. For solar, GenCost assumes a capacity factor of 19 to 32% and for wind 29 to 48%. But CIS analysis has shown average capacity factors for solar and wind farms in the eastern states over the last year were around 20% and 29%, respectively. Those numbers are at the absolute bottom of the overly optimistic range assumed by GenCost. The CSIRO also does not include offshore wind in its wind and solar estimate because it is too expensive – but the Victorian government’s commitment to offshore wind means consumers will face those extra costs.

By fixing only some of the unrealistic assumptions for the cost ranges in the GenCost model – economic life, capacity factor and storage costs – renewables go from being much cheaper than nuclear to being roughly the same cost. Choosing a point estimate with the most realistic capacity factors means nuclear comes out as the clear winner.

The GenCost report itself states that it “is not a substitute for detailed project cashflow analysis or electricity system modelling which both provide more realistic representations of electricity generation project operational costs and performance”. This is where the ISP comes in.

Unlike GenCost, AEMO’s ISP is designed to be a full system model, but this model has serious flaws.

The ISP’s biggest flaws are uncosted ‘spongy fillers’ that would not be available to support the system in the real world. The model relies on ultra-flexible hydrogen electrolysers to soak up excess energy when needed, which boosts the capacity factors of renewables. It also relies on consumers buying staggering amounts of home batteries – and handing over control to grid operators – while charging their EVs when it suits the grid, not their schedules. Another issue is batteries are assumed to have perfect foresight of the weather to optimise charging and discharging – in reality, unpredictable weather means optimal charging cannot occur.

All of these uncosted ‘spongy fillers’ in the ISP modelling hide the true costs renewables will add to the system.

Mr Bowen and other renewables advocates have been quick to attack the Coalition’s favoured Frontier Economics model – particularly for its capacity factor and economic growth assumptions – without realising that its flaws originated in the ISP. Frontier intentionally mirrored the government’s favoured modelling to ensure a like-for-like comparison.

One common critique is that Frontier’s 90% nuclear capacity factor is unrealistically high. Critics have argued nuclear plants making up 38% of grid generation would not be able to operate continuously when wind and solar are providing half of our electricity needs. But the same is true for the ISP’s renewables capacity factors. Just like GenCost, the ISP model is overly optimistic about solar and wind, assuming capacity factors of 25% and 35% respectively, instead of the more realistic 20% and 29%, as shown above.

These capacity factors are made possible by the uncosted ‘spongy fillers’ present in the ISP and Frontier models. But crucially, renewables rely on these modelling crutches far more than nuclear. If these flaws were fixed and the crutches taken away, the ISP’s renewables plan would be the first to fall. This is because nuclear – being a 24/7 source of energy – better matches demand than weather-dependent renewables. Frontier’s modelling therefore likely underestimates the cost reduction benefits of including nuclear in the real electricity system – where modelling crutches do not exist.

Mr Bowen has also criticised the Coalition for “asserting that costs will be lower because Australians will use less power”. But once again, the Frontier model copies its scenarios – including economic growth assumptions – directly from the ISP. In both the Coalition’s preferred scenario and the government’s preferred scenario, the Frontier analysis shows nuclear lowers system costs by 25% compared to Labor’s renewables plan.

As it stands, only the Coalition has commissioned a full system model testing both parties’ plans. The ISP represents a perfect opportunity for the Labor government to prove its renewables plan beats a nuclear option at decarbonising the grid at lower cost. But because AEMO strictly adheres to government policy, the ISP does not consider nuclear at all. It’s unclear why Mr Bowen has not requested AEMO test the nuclear option – perhaps he is not confident the results will be in his favour.

International examples support Frontier’s conclusion that including nuclear reduces the costs of decarbonisation. The US Department of Energy’s Liftoff Report indicates nuclear reduces costs by 37% compared to an all-renewables system. Germany became the industrial powerhouse of Europe by relying on cheap coal and nuclear, but has now closed all its nuclear plants in favour of a massive expansion of wind and solar. Data from the German Chamber of Industry and Commerce indicates 40% of industrial companies are now considering partly or fully relocating operations abroad due to a lack of affordable and reliable energy.

Labor would do well to learn from global experience of the economic impacts of nuclear versus renewables. The government’s opposition to nuclear has already isolated Australia from its closest allies – the federal government recently refused to join the US and UK in signing an agreement to speed up development of advanced nuclear technologies. Australian Labor’s three-eyed fish memes and labelling of nuclear as “risky” is a far cry from the UK Labour Prime Minister calling nuclear “a critical part of the UK’s energy mix” or the Biden administration planning to triple nuclear capacity by 2050.

The government can keep citing its favoured experts claiming nuclear will be more expensive than renewables. But it can’t change the international reality that nuclear energy reduces the cost of decarbonisation, while reckless pursuit of a system dominated by wind and solar is a surefire way to strangle a country’s economy.

Zoe Hilton is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Centre for Independent Studies.

Photo by Pixabay.

The cost of nuclear: some clarifications