Home » Commentary » Opinion » Parents need NAPLAN data, not states hiding school performance

· Australian Financial Review

NAPLAN and My School were introduced for good reasons and continue to serve an important purpose. Yet they are constantly under threat from powerful players in education policy – especially education unions, who have been waging a relentless and hostile campaign that has erupted into the current stoush.

NAPLAN and My School were introduced for good reasons and continue to serve an important purpose. Yet they are constantly under threat from powerful players in education policy – especially education unions, who have been waging a relentless and hostile campaign that has erupted into the current stoush.

But without national assessment and reporting, there would be no objective and reliable information about school and system performance to guide research, policy and teaching practices; and parents would be in the dark about the progress of their children and the schools they attend.

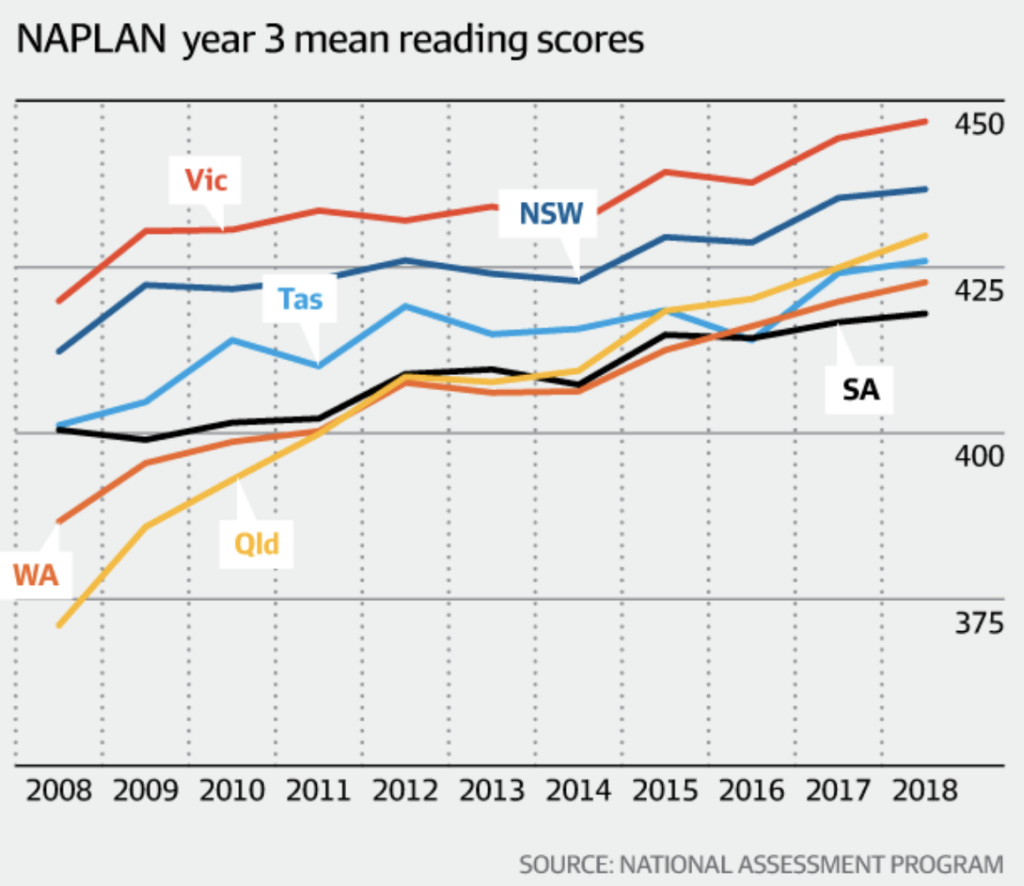

Without NAPLAN, we would not know Year 3 reading levels in most states have improved in recent years but numeracy has not. NAPLAN data has also been used in research showing high-performing schools are not always the schools with the most funding or the children from the richest families.

NAPLAN should not be taken for granted. Prior to 2008, it was almost impossible for anyone outside of state and territory governments to obtain information about the academic performance of schools. This was not because the information wasn’t collected – every state and territory had literacy and numeracy testing in at least years 3, 5 and 7. It was because governments would not allow anyone to see the data.

As a relatively new policy analyst in 2003 who was keenly interested in what drove school performance, this was a source of immense frustration. I wrote a report called Schools in the Spotlight that called for school performance data information to be published in an accessible and responsible way. The report proposed the literacy and numeracy results be published as school averages, with state and “like school” comparisons and a growth measure, alongside information about school programs, resources and other indicators.

The basic rationale for NAPLAN is that it is important to have a measure of student learning. This is to firstly ensure children are getting the fundamentals of literacy and numeracy, and secondly for school and system performance analysis and accountability. For this measure to be meaningful, it must be consistent and comparable both within cohorts and over time. This is no easy thing to achieve and no test is ever perfect, but NAPLAN is effective.

The rationale for My School is if governments collect and analyse data on student and school performance, it should not be kept secret from parents and the public. The furphy that people will “misuse” this information if it is made public is patronising and untrue.

My colleague Blaise Joseph recently examined the validity of common criticisms of NAPLAN and found them to be groundless. One is that NAPLAN is high-stakes and forces schools to “teach to the test”. There are no “stakes” attached to NAPLAN performance – there are no incentives for high achievement or consequences for low achievement.

If schools “teach to the test”, this is arguably a good thing if it means they are focused on ensuring all students are proficient in reading, writing, and numeracy. If it means they are drilling students with practice tests, that is not “teaching to the test” … it is simply bad teaching.

There is also little basis to the claim NAPLAN is causing an anxiety epidemic among children. The assessments are not inherently stressful; most children take them in their stride and any anxiety they might feel is likely to come from the adults around them.

NAPLAN does not quantify in a single set of numbers the entire range of abilities or achievements of any individual child or school. It can be improved – and the new NAPLAN Online will provide better data and more quickly – but it is essential.

NAPLAN is helpful for parents who want an external reference point for their child’s literacy and numeracy achievement. It provides detailed data at a class level indicating gaps in teaching and learning that need to be rectified. Schools can use the data as a cross-check with other assessments they are using. For regions and systems, NAPLAN data can highlight high-performance and flag problems.

Instead of undermining NAPLAN, all education ministers and officials should be working on how to make sure its data is as valid and accurate as possible, so systems can see which policies are working, and schools can use it to inform improvements to teaching and learning.

Let’s not return to the education data dark age when school reputations were built on smartness of the uniforms and school gate gossip.

Dr Jennifer Buckingham is a senior research fellow at The Centre for Independent Studies.

Parents need NAPLAN data, not states hiding school performance