Home » Commentary » Opinion » Australian universities can’t rely on India if funds from Chinese students start to fall

· The Conversation

Australia’s leading universities are now looking to India in search of new sources of international students. This comes amid worries they may have reached a “China max” – no more room for growth in Chinese students and numbers at risk of falling.

Australia’s leading universities are now looking to India in search of new sources of international students. This comes amid worries they may have reached a “China max” – no more room for growth in Chinese students and numbers at risk of falling.

The question of whether India is a potential solution is something I looked at for my latest report published today for the Centre for Independent Studies.

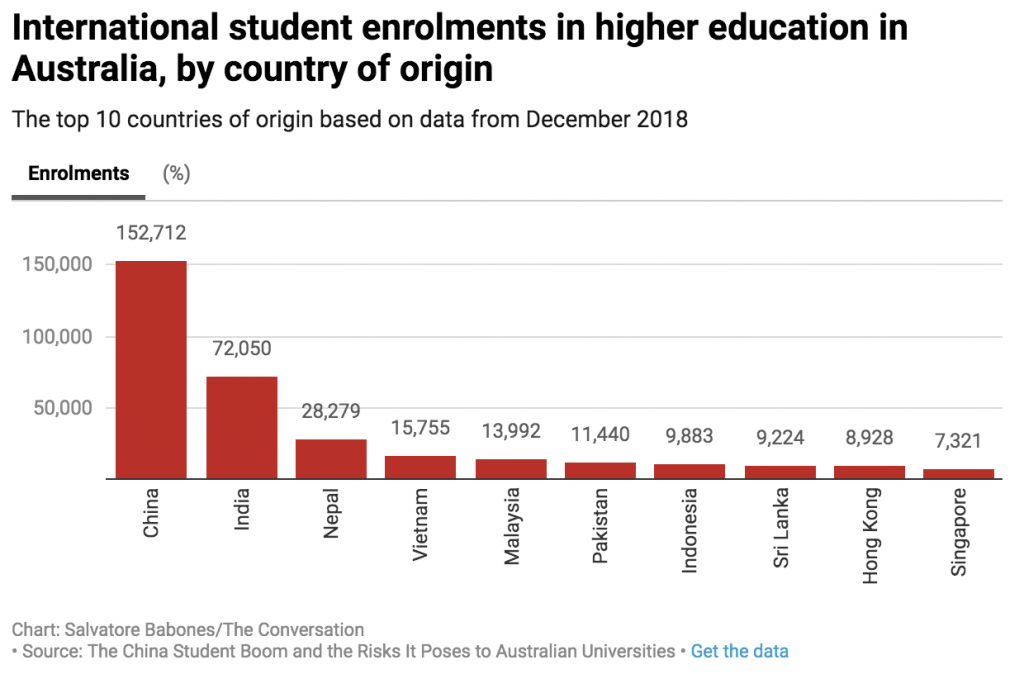

My research found Chinese students currently make up about one in ten students at Australian universities. They’re about 40% of the total international student intake. But that’s after a rapid period of growth that slowed dramatically in 2018 and has now come to a virtual standstill.

From a business perspective, investing so much in one portfolio is risky, and universities need to diversify where they’re getting their income to ensure a stable economic future.

UNSW last year opened a new centre in Delhi as part of its India Ten Year Growth Strategy. The University of Sydney’s 2018 annual reporttalked of this year appointing an “in-country team” in India to “recruit high-calibre students”. The ANU’s 2017 annual report talked of “scoping” an India office.

The University of Queensland has an India-focused approach to increasing international student revenue. That comes as no surprise as last year, UQ Chancellor Peter Varghese delivered an India Economic Strategy report to the Australian government.

In one of his recommendations (6.1.1) he says Australia should:

Make India a priority market as part of the global refresh of Australia’s education brand.

The latest annual reports of these four universities (UQ, UNSW, ANUand Sydney) show they draw more than 30% of their student bodies from overseas.

With international students paying several times the tuition of domestic ones and the China market now appearing to be tapped out, India is widely seen as the next major source of “cash cows”, as ABC put it in a recent Four Corners investigation on universities and the billions of dollars they make from foreign students.

India is in fact the world’s second-largest source country for international students, and although it trails China by a wide margin, the country is growing fast.

Australia’s universities seem to believe they can replicate their wildly profitable China expansion in India. But they’re wrong.

My research shows India is still far too poor to become the next “cash cow” for Australian universities.

There are around 24 million adults in China with incomes over A$50,000 a year, according to calculations based on data from the World Inequality Database. That compares to just three million for India.

That makes the potential Indian market for Australian degrees roughly one-eighth the size of the Chinese market.

In fact, every province of China is richer than every state or territory of India with the exception of the tiny tourist enclave of Goa (population 1.5 million), according to data from each country’s statistical service.

Recent scholarships, targeted at Indian students might be attempts by Australian universities to diversify their international student profiles away from a total reliance on China.

But while subsidising Indian students may reduce the concentration of Chinese students in their courses, it will do nothing to reduce their financial dependence on China. In fact, it will increase the proportion of their net income derived from China. Which brings us back to the problem of “China max”.

Some Australian universities I looked at draw between 13% and 23% of their revenues from Chinese student enrolments.

I’ve identified a number of risk factors that could adversely affect the number of Chinese students in Australia. By far the most serious are the macroeconomic factors – such as any slowing of China’s economy and fluctuations in the value of the Australian dollar – that could lead to a sudden and severe fall in Chinese enrolments at Australian universities.

Many investors will tell you that to reduce risk, you should seek to limit your exposure to any one investment (in this case, one source country of foreign students) to no more than 5% of your portfolio. Something akin to the phrase “don’t put all your eggs in one basket”.

Australian universities need to take steps to reduce their over-reliance on international students for sources of funding, and within that revenue stream, to reduce the reliance on one or two source countries.

Australian universities can’t rely on India if funds from Chinese students start to fall