Home » Commentary » Opinion » Inquiring about the elephant in the classroom

· Ideas@TheCentre

It is easy to understand why people find the idea of inquiry learning so appealing. It’s a lovely notion that children can and will learn important concepts and knowledge simply by being given an opportunity to discover them for themselves.

It is easy to understand why people find the idea of inquiry learning so appealing. It’s a lovely notion that children can and will learn important concepts and knowledge simply by being given an opportunity to discover them for themselves.

This is allegedly the education of the future — a future in which children need only to learn how to find what they need at the time they need it.

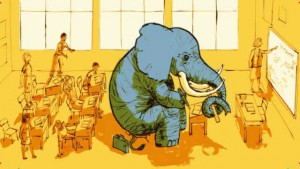

But is it true that children learn best by inquiry? You would think so if you listened to Andreas Schleicher, the Director of the OECD Education Directorate, which runs the Program for International Assessment (PISA). Professor Schleicher was in Australia recently, giving interviews and speaking at events and forums. Disappointingly, he did not mention the pedagogical elephant in the room — that OECD reports show that inquiry learning is strongly negatively associated with PISA scores.

A deeper analysis of the PISA scores by McKinsey and Co found that the ideal balance is for almost all lessons to be teacher-directed with a small number of inquiry-based lessons. This fits well with the cognitive science-informed framework in which novice learners need more highly structured, explicit teaching, with a gradual shift to independent inquiry as they consolidate their knowledge and develop expertise.

The PISA data is supported by numerous other studies showing that explicit, teacher-directed instruction is more effective than inquiry learning.

Strangely, however, the more evidence stacks up against inquiry learning, the more it seems to take on a mythical status of being unassailably superior.

This week the long line of heavy weights endorsing inquiry learning included the Australian Association of Mathematics Teachers, and a German maths professor who happily acknowledged that her version of inquiry learning is not based on cutting edge research but on a centuries-old theory that was refined in the 1920s and popularised in the 1960s.

Inquiry learning can be useful when administered in the right doses at the right time in the learning process. It is not a miracle cure for a new age.

Inquiring about the elephant in the classroom