Home » Commentary » Opinion » Tax cuts in the never-never and a messier system now

· Financial Review

The new low and medium income tax offset greatly complicates the tax system, dulling incentives and making reform more difficult.

The new low and medium income tax offset greatly complicates the tax system, dulling incentives and making reform more difficult.

The personal income tax changes in the 2019-20 federal budget are a curate’s egg of good and bad. They serve a macroeconomic purpose of boosting household disposable income – and therefore consumer spending capacity – in the short term. But they postpone for several years any meaningful steps to meet the microeconomic need for stronger incentives in the tax system through lower marginal rates.

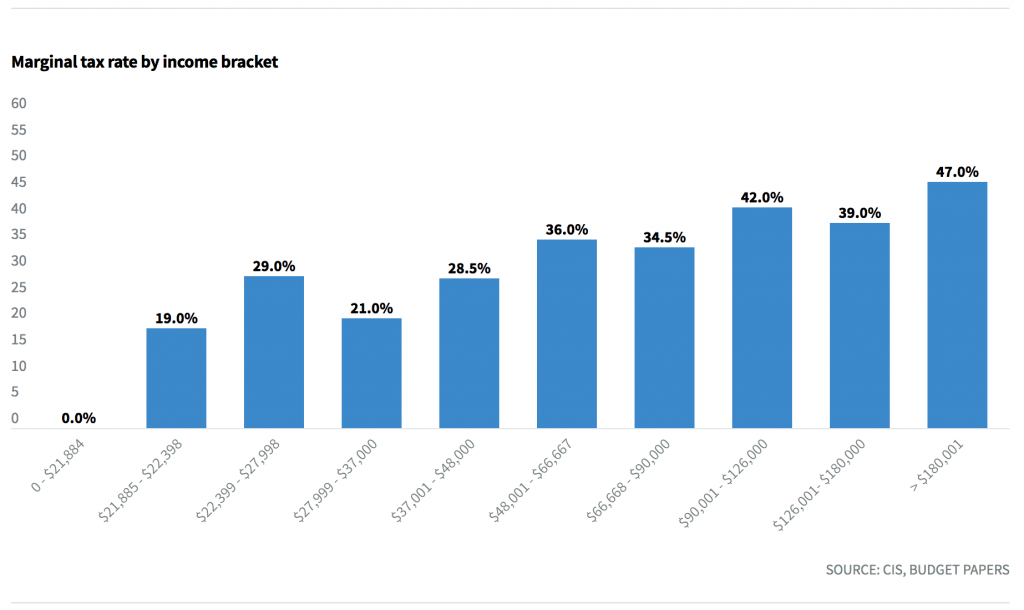

Cuts to marginal rates deliver the most durable tax relief and do the most to boost incentive. The government’s proposals to lower the 32.5 per cent marginal rate (34.5 per cent including Medicare levy) to 30 per cent and eliminate the 37 per cent rate (39 per cent) are welcome. Both rates are relics of past tinkering with the tax scale and are long overdue for reform.

It is disappointing – though hardly surprising – that no reduction in the top rate is being proposed. However, did the budget speech need to boast about how highly progressive the income tax system is and how the government’s changes will keep it that way? This is a sign of the times and illustrates the extent to which those who would normally advocate incentive and low taxes are bending to leftist sentiment.

Labor of course plans to lift the top rate to 47 per cent (or 49 per cent including Medicare levy) – a move now demonstrated to be clearly unnecessary to meet its stated purpose of producing a budget surplus.

Any increase is welcome, but 11 per cent after what will be 15 years since the last increase is wholly inadequate.

Part of the government’s plan involves lifting the thresholds at which marginal rates cut in. It plans to raise the $37,000 threshold for the 32.5 per cent marginal rate to $45,000 before that rate is cut to 30 per cent. This is welcome, as this threshold has lagged the large increases in the others. An adult full-time worker on the minimum wage is now above the $37,000 threshold.

Then there is the proposed increase in the top rate threshold from $180,000 to $200,000, announced in the 2018 budget. Any increase is welcome, but 11 per cent after what will be 15 years since the last increase is wholly inadequate.

Tinkering with thresholds eventually becomes unavoidable if only to adjust for inflation, but a better way is to index thresholds automatically to the CPI or average wages. Neither the Coalition nor Labor seems willing to go anywhere near such a reform.

But the biggest problem is that none of the above threshold or marginal rate changes are slated to happen until 2022 at the earliest and in some cases 2024, and in the meantime all we will see is a lot of action on the low and middle-income tax offset (LMITO).

If the government is re-elected, fiscal exigencies may intervene, not to mention another election in 2022.

Politics being what it is, the safest working assumption is that what is planned for 2022 and 2024 will not happen. This is the problem with multi-year tax cut plans stretching way into the future. However good the intentions behind them, they are best taken with a grain of salt.

If the government is re-elected, fiscal exigencies may intervene, not to mention another election in 2022. If Labor takes the fiscal reins next month, the 2022 and 2024 changes are even less likely. Labor’s policy details will be revealed in due course, but we know from its reaction to last year’s budget it will seek to repeal the already legislated 2022 and 2024 changes and rely solely on increases in LMITO to deliver tax relief.

While Labor intends the increase in LMITO to be permanent, the government’s plan is to increase it temporarily – essentially to deliver a means-tested version of its longer-term changes in marginal rates and thresholds and contain the short-term revenue cost.

The problem with LMITO – whether temporary or permanent – is that it tilts the focus of the personal income tax system from efficient revenue-raising to welfare, in the sense that it is an income support measure for low and middle-income households. It allows the target group of taxpayers to keep more of their pre-tax income, but it does not improve incentive by reducing marginal rates other than incidentally.

It also greatly complicates the income tax scale, and will result in ten effective marginal rate bands.

LMITO lowers effective marginal rates over some income ranges but also increases them over some income ranges as it is phased out for higher-income earners. For example, phasing out the $1080 LMITO between $90,000 and $126,000 will result in a new and higher effective marginal rate of 40 per cent (42 per cent including Medicare levy) over that range.

It also greatly complicates the income tax scale, and will result in ten effective marginal rate bands, and the Medicare levy has its own thresholds that create even more bands.

LMITO isn’t reform, but it could be accepted as a transitional measure on the road to reform. The worry is that it will become entrenched while meaningful reform falls victim to politics in the age of populism, sluggish real wages and false assertions about inequality.

Robert Carling is a senior fellow at the Centre for Independent Studies and a former IMF and federal and state treasury official .

Tax cuts in the never-never and a messier system now