Home » Commentary » Opinion » Nuclear vs Renewables – which is cheaper?

· ENERGY NEWS BULLETIN

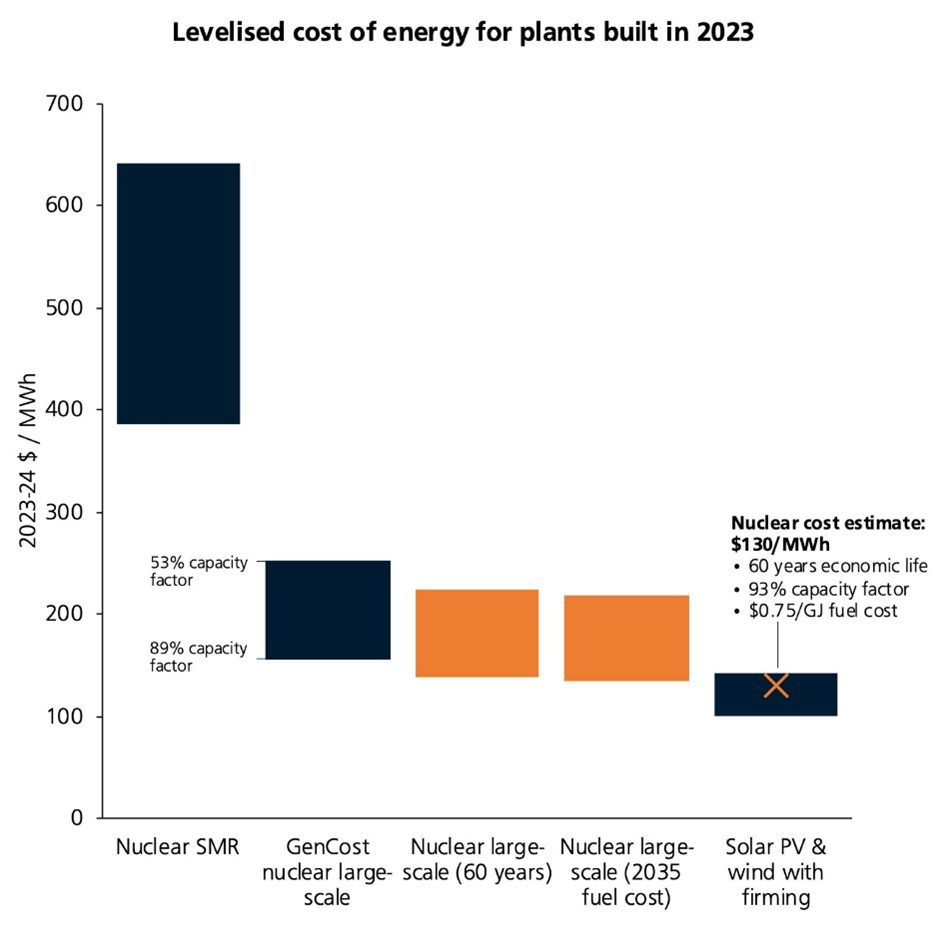

One of the most common objections to Australia pursuing nuclear power is that it is allegedly too expensive. This claim originates from the CSIRO’s GenCost report, which asserts that nuclear is around double the cost of wind and solar. However, Centre for Independent Studies analysis has shown that correcting some of the GenCost model’s unrealistic assumptions would negate this objection.

In fact, nuclear is easily cost-competitive with renewables – and is likely cheaper when compared with the actual costs Australians will face to firm renewables.

The 2024 GenCost report’s 90% firmed renewables LCOE came out as $100/MWh to $143/MWh, while large-scale nuclear was estimated to be between $155/MWh to $252/MWh. This means the lower bound of nuclear is already fairly close to the upper bound of renewables.

But simply inputting more realistic values for economic life, capacity factor and uranium price into the GenCost model shows that nuclear falls well within the renewables cost range.

First, GenCost assumes an economic life of 30 years for nuclear plants. This is because GenCost estimates the costs an investor would face for different generation technologies, and investors typically want investments paid off within 30 years.

However, nuclear reactors are already being licensed for 60 years, with regulators even considering 100-year licences, given the longevity of central reactor structures. This means consumers can enjoy cheap electricity from a nuclear plant many decades after the capital costs have been paid off.

Second, GenCost assumes a capacity factor of 53% to 89% for nuclear plants. This is very low, as it assumes nuclear plants must ramp down to allow wind and solar to dispatch. For comparison, the US nuclear fleet averaged 93% over the last two years.

A better strategy to keep down costs for the whole grid would be to prioritise clean, reliable nuclear power rather than forcing it to ramp down to make room for unpredictable wind and solar output.

Finally, the GenCost model locks in for the entire life of a nuclear plant the uranium price spike of $1.10/GJ to $1.30/GJ resulting from the recent US ban on Russian fuel. This is despite GenCost, itself, projecting uranium prices will come back down to between $0.80/GJ to $1.00/GJ by 2030. Thankfully, because uranium is still a cheap fuel, this assumption has less impact than the previous two factors.

As our analysis shows, fixing these three unrealistic assumptions in the GenCost model gives a cost estimate for nuclear of $130/MWh – right in the range of firmed renewables, showing it is clearly competitive with wind and solar.

But this only addresses CSIRO’s assumptions around nuclear – what about renewables? Instead of getting bogged down in theoretical modelling, let’s come back to the real world and look at just how much Australia is already planning to spend on firming infrastructure.

Tallying up the costs of the currently planned pumped hydro projects in the National Electricity Market – Snowy 2.0, Pioneer-Burdekin and Borumba – gives a total of $38.2 billion.

Doing the same for the many transmission projects currently being approved – VNI West, HumeLink, Central-West Orana REZ, New England REZ, Sydney Ring, Gladstone Grid Reinforcement, Queensland SuperGrid South, CopperString and Project Marinus – comes to a total of $34.6 billion.

This means Australians are set to pay $72.8 billion for pumped hydro and transmission that don’t produce any electricity and are simply there to firm intermittent wind and solar energy.

Taking at face value GenCost’s capital cost estimate of $8.7 billion to build a 1GW reactor, $72.8 billion is enough to buy eight large-scale nuclear reactors.

This $72.8 billion figure doesn’t even include the wind turbines and solar panels themselves, or the long list of battery projects currently underway, or the future transmission and storage projects that a renewables-dominated grid will need by 2050.

How many reactors could we afford if we added in just one more chunk of these significant costs?

A recent Centre for Independent Studies paper, The six fundamental flaws underpinning the energy transition, calculated the cost at today’s prices of all the consumer batteries we’d need to support the grid by 2050 according to AEMO’s Integrated System Plan, using GenCost’s capital cost estimates.

The total comes to $229 billion.

Adding the cost of these consumer batteries to the transmission and pumped hydro costs gives you an eye-watering $301.8 billion. That means the amount Australians are set to spend on firming infrastructure in the next few decades is enough to buy 35 1GW reactors.

To put this in perspective, the peak demand for the entire National Electricity Market in 2024 was 38 GW. So for the price we’re paying just to support intermittent wind and solar, we could afford to build even a 90% nuclear grid that is cheap, clean and reliable.

It is now abundantly clear, despite anti-nuclear advocates’ claims to the contrary, that nuclear power is not exorbitantly expensive, especially when we consider how much Australian consumers are paying — and will continue to pay — to support intermittent renewables.

Zoe Hilton is a Senior Policy Analyst in the Energy Program at the Centre for Independent Studies.

Nuclear vs Renewables – which is cheaper?