Home » Commentary » Opinion » Winds of global change hold risks for Xi’s ambitions

· The Australian

The AUKUS announcement, followed within hours by China’s application to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership trade pact, is forming the centre of our foreign affairs discussions now. But such debates often take place without paying attention to their most important framing: China’s own changes.

The AUKUS announcement, followed within hours by China’s application to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership trade pact, is forming the centre of our foreign affairs discussions now. But such debates often take place without paying attention to their most important framing: China’s own changes.

The Chinese Communist Party is at the peak of its power as it enters its second century, coveting all loyalty everywhere. Its core goal is to control its destiny. It does so within China, where it rules unchallenged, removing all space, all oxygen, from any independent or variant thought, organisation, business or individual.

It also increasingly is set on making the wider world adapt to it, rather than having to adapt itself to international values, laws or trends. Just as its own population is accountable to its leadership, so it seeks to mould global patterns to its own priorities.

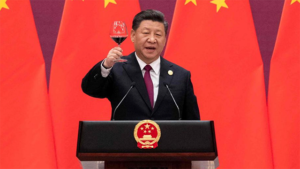

President Xi Jinping has instructed the CCP to “build a socialism that is superior to capitalism” and that will occupy “the dominant position” in world affairs. Its tentacles are enfolding China, its history, culture and people ever more tightly with the aim of making it impossible to prise party and country apart.

But in recent years party membership has become more managerial and middle class than proletarian or peasant-based, and “red genes” now are required for serious elevation in its ranks. The party and its officials effectively own China’s sovereignty, and thus are separated out as the established ruling class from their fellow countrywomen and men.

Protecting the party’s version of history has become such a priority because it lies at the core of its legitimacy among the people of China. The party’s role in helping families to prosper came to the fore during the previous reform era but has lost its legitimising centrality as the rising generation has come to take that prosperity for granted, and as Xi’s New Era has elevated the “core leader”and the party as its focal points.

Beijing’s pandemic response has reinforced this process in a country that already was in effective intellectual and institutional lockdown before Covid-19 emerged. Xi has labelled stepped-up Covid era controls, including the broad sharing of personal data between government agencies, as “full-circle management”.

The party also has reverted to intense centralisation of decision-making and to elevating Xi to personality cult status. This injects an added degree of vulnerability into the party’s future.

How is Xi to be succeeded, as his role takes on ever greater weight and as, aged 68, he shows no sign of stepping aside, perhaps for a decade at least? The answer matters, not only for China but also for the world. While the impact of past power struggles was largely contained within China’s borders, the global fallout from a succession crisis would be huge.

Engagement is no longer a useful template for relating to this behemoth, with China resiling from being a ready partner as it increasingly sets itself apart including economically. But every country must find a way to live alongside it, preferably beneficially and, as far as can be ensured, safely.

China remains a lonely great power, without friends or – except for North Korea – allies. Even its capacity to weaponise its economic heft to achieve international goals is set for steady erosion as the natural maturing of its economy, its ecological challenges, its party’s growing disinclination to accommodate entrepreneurship, take their inevitable steady toll.

The party, self-assured about its historic destiny, presented itself during its centenary celebrations in July as set to triumph over an inwardly-facing Western world whose intellectual class pushes not only to critique but to discard that world’s history, values and culture.

And strategically, the Taliban’s recapture of Afghanistan soon after its leader held friendly talks with China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi – presenting the prospect of a great arc of Chinese influence running to and beyond Iran – underlines one of Xi’s great themes, Western decline. Yet the party faces serial risks including China’s imminent rapid demographic decline, the continuing march of Christianity offering a contrasting set of values and beliefs, and the potential for a debacle over its ambitions to annex Taiwan.

And other countries, especially in China’s own region, are developing a modest but growing resilience to push back against efforts to mould global patterns to party priorities. That pushback comes not only from liberal democracies but also from other kinds of states whose populations are becoming increasingly worried about China’s role despite their elites’ Beijing deals.

Xi’s keynote speech in Tiananmen Square at the party centenary rally chiefly looked to the CCP’s historic successes and to the glorious present. He failed to map out a meaningful program for the future. The main message to the 70,000 gathered leading cadres was to keep on keeping on. Stay strong. This is likely to prove steadily harder to achieve as winds of global change blow unpredictably and dangers – including disinterest – lurk within the fog of apparent unquestioning compliance at home.

Rowan Callick’s new paper on this theme, Xi Dreams of 100 More Glorious Years for the Party: Might China Awake?, is published by the Centre for Independent Studies and available free online. He is an Industry Fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute.

Winds of global change hold risks for Xi’s ambitions