Bracket creep hits young Australians the hardest

Bracket creep chips away at living standards, especially those of younger generations. Australia’s younger workers have the most to lose from bracket creep because they are early in their careers and make less money. Young people feel the impact of a tax increase more acutely than those established in their careers with higher incomes and more wealth.

The tax increases faced by those at lower incomes are also larger with only a small increase in nominal income leading to a large increase in their overall tax rate.

Young people have less bargaining power and will likely struggle to convince their employers to make cost-of-living adjustments to their earnings, let alone the rise needed to compensate for both inflation and a higher tax rate due to bracket creep.

Periodic tax cuts only help temporarily; they barely scratch the surface in offsetting bracket creep’s insidious impact. To genuinely tackle this issue, Australia needs a long-term solution that does not depend on the whims of politicians. Do you really want to rely on politicians to protect you from tax hikes you didn’t vote for?

Introduction

When your pay increases, so does your tax rate — thanks to Australia’s ‘progressive’ tax system. But these tax hikes hit you even when your pay is just keeping pace with the cost-of-living. This happens through a hidden tax known as ‘bracket creep’.

The Australian government could abolish these sneaky tax increases by shifting tax brackets with inflation — a process known as ‘indexation’.

This policy snapshot explains how bracket creep occurs and what the government should do to stop this hidden tax hitting our younger generations when they are already struggling with a cost-of-living crisis.

How bracket creep hits you

Figure 1: Increasing marginal tax rates mean higher overall tax rates at greater incomes

Bracket creep occurs because Australia has a progressive tax system, where higher income earners have higher marginal tax rates than lower income earners, and tax is based on nominal income not your real income.

As your nominal income increases Even if you don’t cross into the next tax bracket. Even when your real income remains the same.

For those at lower incomes any increase in salary leads to an abrupt increase in the overall tax rate. This can be seen in Figure 1. The curve starts out steep where incomes are low and levels out as taxable income increases.

Nominal Income vs Real Income

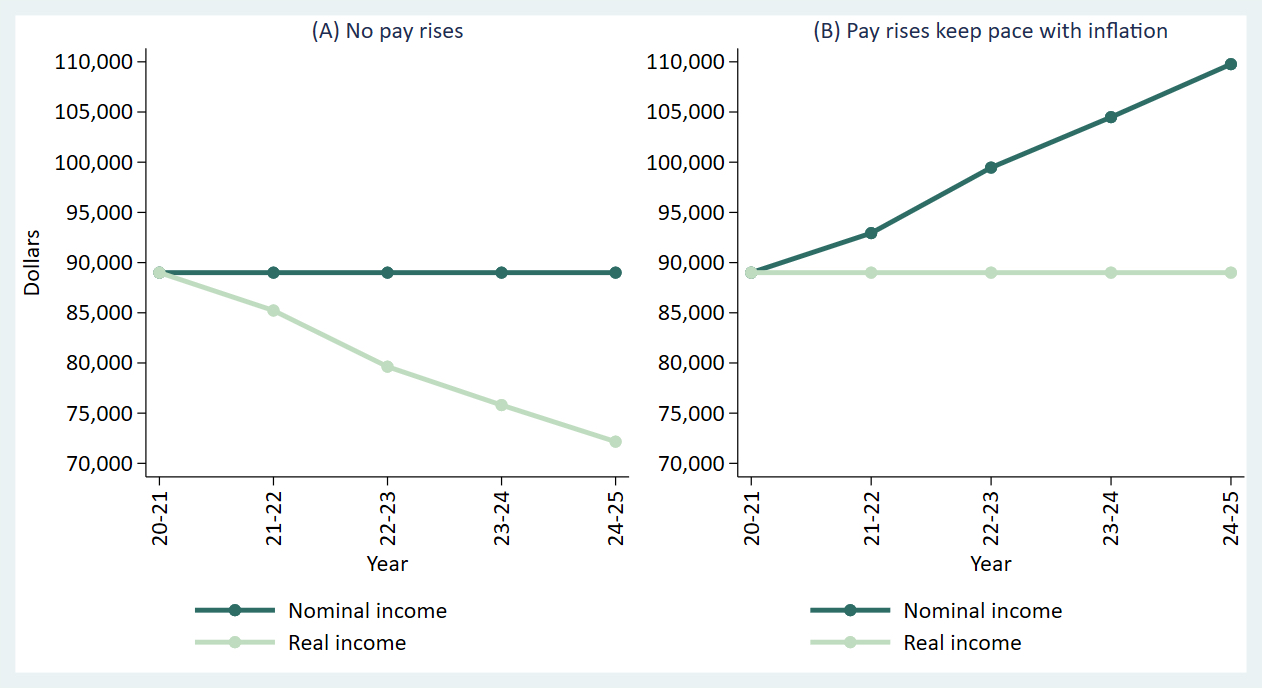

Over time, inflation erodes the value of a fixed level of income. If your pay (nominal income), does not keep pace with inflation, your real income will decrease as shown in Figure 2A. If your real income is to remain the same, you must receive regular pay rises to maintain your standard of living as shown in Figure 2B.

Why? Because Australia’s income tax brackets don’t increase in line with inflation but remain fixed until the government passes tax cuts. As your pay increases, more of your income is taxed at your top marginal tax rate, resulting in an increase in your overall tax rate.

Figure 2: Nominal income versus real income

Source: CIS modelling based on ABS (2023a), ABS (2023b) and ABS (2023c).

Notes: The real incomes in the figure assume the annual rate of inflation in 2023-24 and 2024-25 will be 5.05 per cent. This is the average of monthly inflation observed over July and August 2023 which was the most recent data available at the time of writing, see ABS (2023c).

The impact of bracket creep on the average worker

Take Jane, on an average wage of $89,000 in pre-tax income in 2020-21.[i] She pays $19,392 in tax, leaving her with $69,608 to spend. However, with inflation at 4.4%, in one year her earnings will only be worth $85,229 in real terms.

Jane — not unreasonably — feels her standard of living should keep pace with the cost-of-living and asks her boss for a 4.4% pay rise. Her boss agrees and pays her $92,938 (before tax) the following year.

With tax thresholds fixed at their 2020-21 levels, Jane’s nominal pay rise increases her tax bill by an additional $404 in real terms. This bracket creep has caused her real after-tax income to fall from $69,608 to $69,204. Her standard of living has decreased not because of inflation (she was able to negotiate a cost-of-living adjustment), but because of bracket creep.

The amount of additional tax may seem trivial. However, as long as tax brackets remain fixed, Jane will have to pay annual tax increases until the government provides tax cuts.

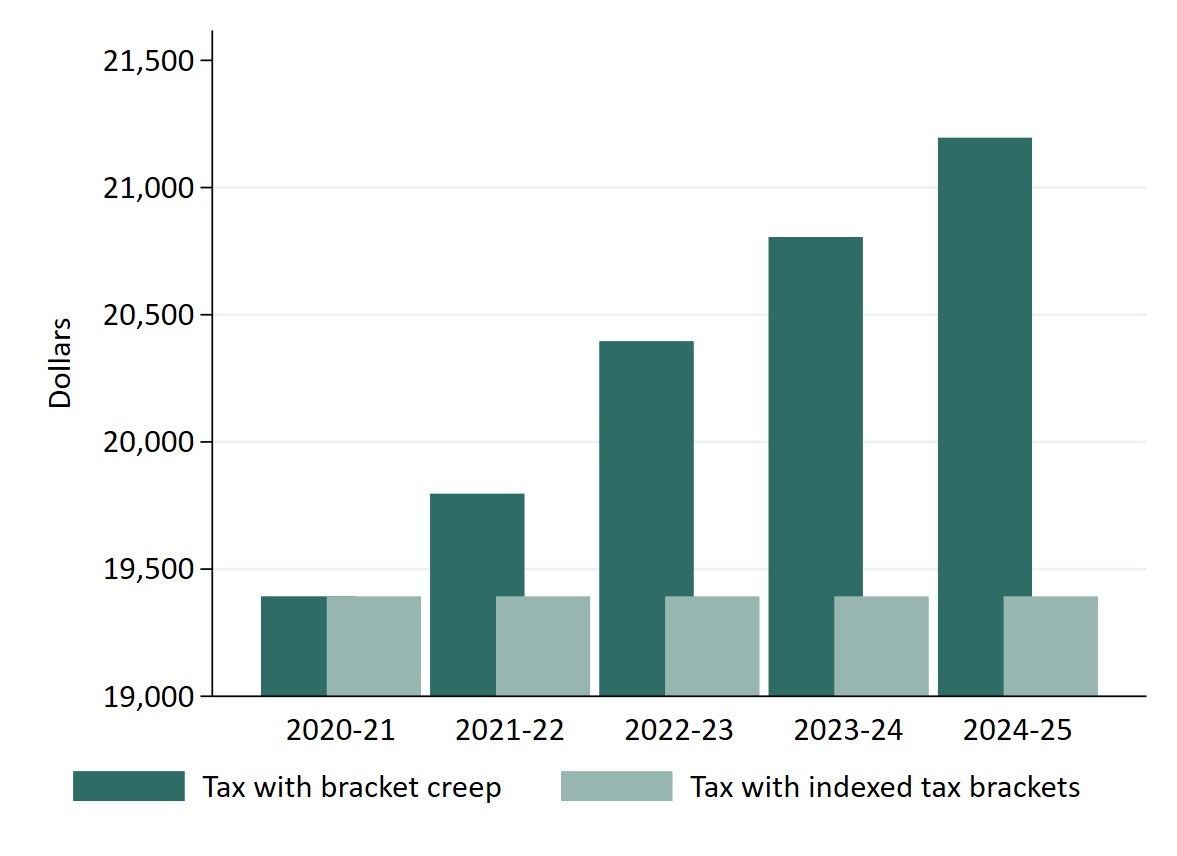

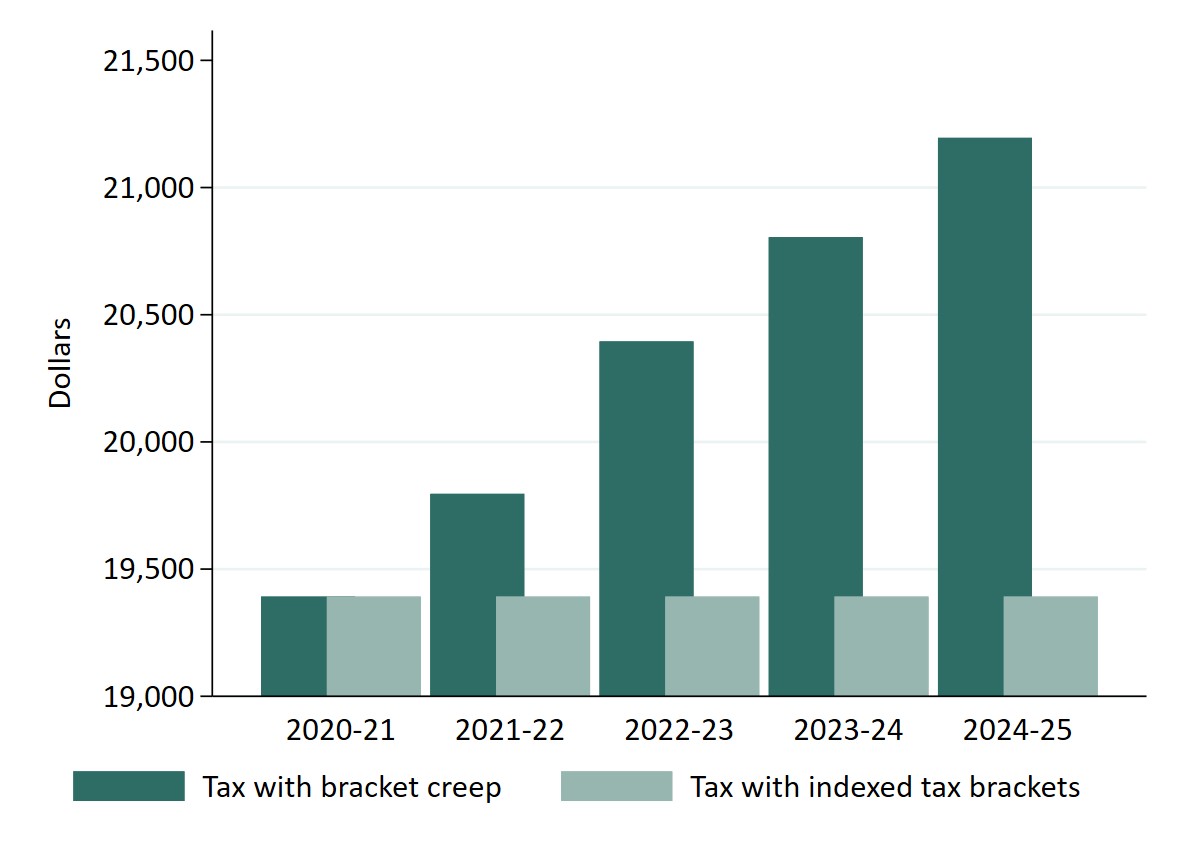

Figure 3 compares the tax Jane has to pay under current policy with what she would pay if tax brackets were increased to keep up with inflation. Bracket creep increases Jane’s tax bill by $1,003 in 2022-23 and $1,413 in 2023-24. Without tax relief in 2024-25, her tax bill will have increased by $4,624 over four years.

These increases are not the result of a change in tax policy. They are built into the tax system because of the government’s failure to implement indexation — increasing tax brackets in line with inflation.

Figure 3: Bracket creep increases Jane’s (real) tax bill

[i] ABS (2023a).

Source: CIS modelling based on ABS (2023a), ABS (2023b) and ABS (2023c).

Notes: Tax payments are presented in 2020-21 dollars under the same inflation rate assumptions in Figure 1. The 2024-25 tax amounts assume bracket creep continue and do not reflect the planned Stage 3 tax cuts.

Do the Stage 3 tax cuts fix bracket creep?

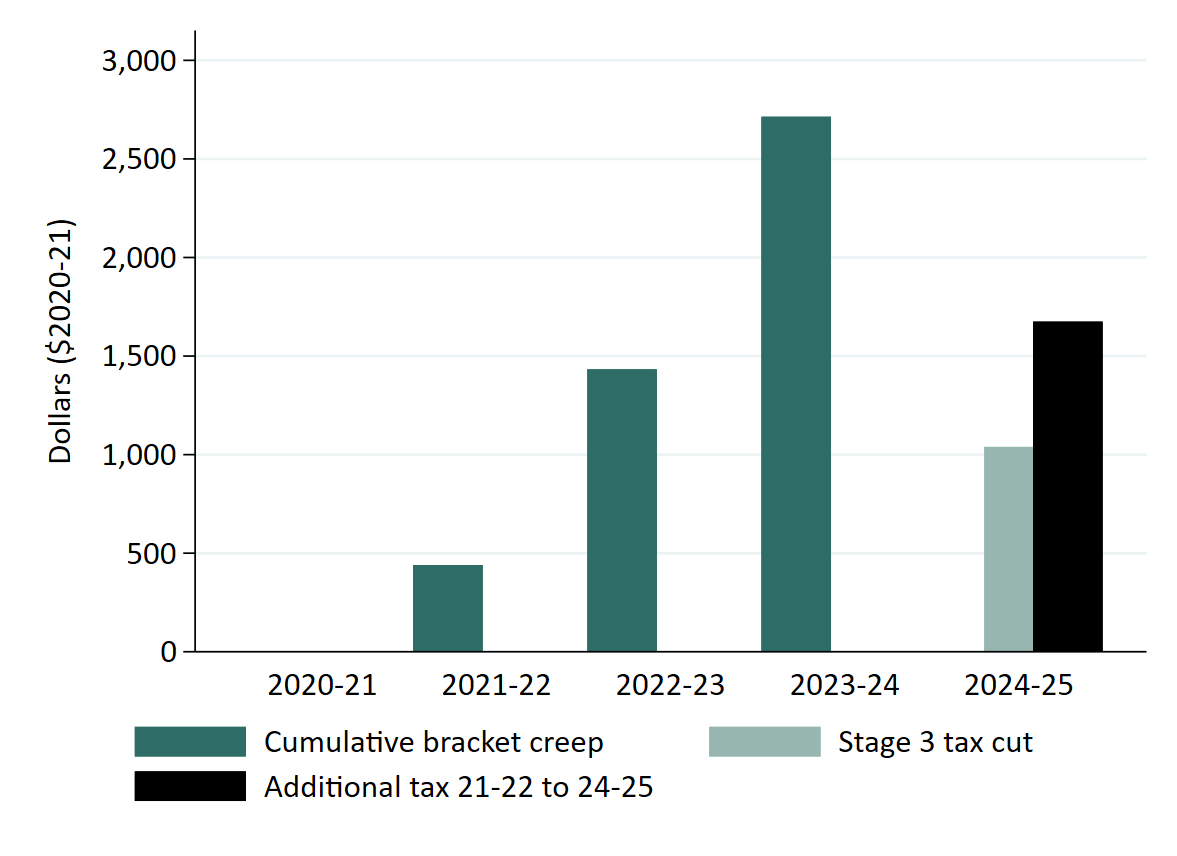

Some argue the government can effectively account for bracket creep through semi-regular tax cuts such as the Stage 3 tax cuts planned for 2024-25. But as Figure 4 shows, this tax cut does little to compensate Jane for the bracket creep she has paid since the last round of tax cuts in 2020-21.

Figure 4: Stage 3 tax cuts do not compensate the average worker for bracket creep

Source: CIS modelling based on ABS (2023a), ABS (2023b) and ABS (2023c).

Notes: Tax payments are presented in 2020-21 dollars under the same inflation rate assumptions in Figure 1. The Stage 3 tax cut is Jacinta’s after-tax income in 2024-25, assuming the Stage 3 tax cuts are implemented, less her after-tax income in 2023-24 in the absence of indexation of tax brackets (both in real terms).

The solution is simple: Index tax brackets to inflation.

The government already does this for Age Pensioners. The Age Pension, unlike tax brackets, is indexed to inflation; ensuring pensioners can maintain the same standard of living. The income brackets used to means-test their pension payments also automatically increase with prices. If pensioners are spared the burden of bracket creep, why not young Australians?

Indexing tax brackets would also fight the cost-of-living crisis

Indexation would help Australians currently facing a cost-of-living crisis. In the 10 years prior to Covid, the annual rate of inflation averaged 2.1%. Inflation in the post-Covid era has almost doubled to 3.9%.

Tax payments are an expenditure. There is only one difference between a tax increase and higher prices at the supermarket: you cannot shop around to reduce your tax bill. Bracket creep further disadvantages workers, sneakily diverting their money to flow to the government.

Indexation would cut the hidden tax hikes that erode real income — a straightforward solution to a complex problem with potential to make a real difference in people’s lives.

Photo by Mikhail Nilov