The media like to report federal budgets in terms of lists of winners and losers, with the unstated assumption that the more winners there are relative to losers, the better the budget is.

This winner/loser view does help focus on what the budget calls ‘policy decisions’, but it is never the whole story — or even the main story — of the budget. In the 2024-25 budget recently tabled by Treasurer Jim Chalmers, it is a struggle to find any losers; unless you count those who failed to get a benefit they had lobbied for.

The deficit budgeted for 2024-25, amounting to over $28 billion ($28,000 million), translates to a willingness to borrow and spend over $1,500 per Australian voter to secure an election victory.

Chalmers announced new spending decisions totalling $12 billion in 2024-25, a total upward spending revision of $17 billion in that year and $47 billion over the next four years, almost nothing in the way of tax increases, and the commencement of previously announced income tax cuts from 1 July worth $23 billion in the first year. It is a budget in which everyone gets a prize.

This may lead voters to take a favourable view of the budget and serve the government’s short-term prospects for re-election, but whether it is in the longer-term national interest and addresses the economic and social challenges facing the nation is another matter entirely. If the budget fails those tests, we will all be losers from it beyond the very short term.

Key tests

Key tests for the budget include:

- Does it contribute as much as it can to the effort to bring inflation down in a sustainable fashion and in so doing effectively address the cost of living ‘crisis’?

- Does it stabilise and strengthen the government’s financial position after the upheavals of the pandemic period?

- Does it help end the long period of productivity stagnation — surely the key to a resumption of growth in real wage?

- Does it answer the national security and major social issues of the times, particularly the high cost of housing?

Test 1: Inflation

Taking these in turn, the $300 electricity bill rebate for everyone was front and centre in the budget’s response to inflation. This attempt to manipulate the CPI by directly reducing consumer electricity bills may seem clever, but it fails to address the underlying inflationary pressures. It could exacerbate these pressures by easing household budget constraints.

An odd aspect of the cost-of-living package is that it contradicts the government’s greenhouse gas emission goals. Subsidising electricity makes little sense for a government committed to net zero emissions, given around two-thirds of our electricity comes from non-renewables.

The cost-of-living package is a foolhardy, populist package, the type done by populist developing-economy politicians. But the inadequacies of the budget as a response to inflation go beyond the CPI hack. It is a big-spending deficit budget at a time when the contribution of government expenditure to aggregate demand needs to be curbed.

Spending is rising sharply in real terms and as a proportion of GDP, and the government does not have a plan to fix the structural deficit. For example, cost blowouts offset the savings it has identified (but not yet achieved) for the NDIS, which has been growing at around 20% per annum.

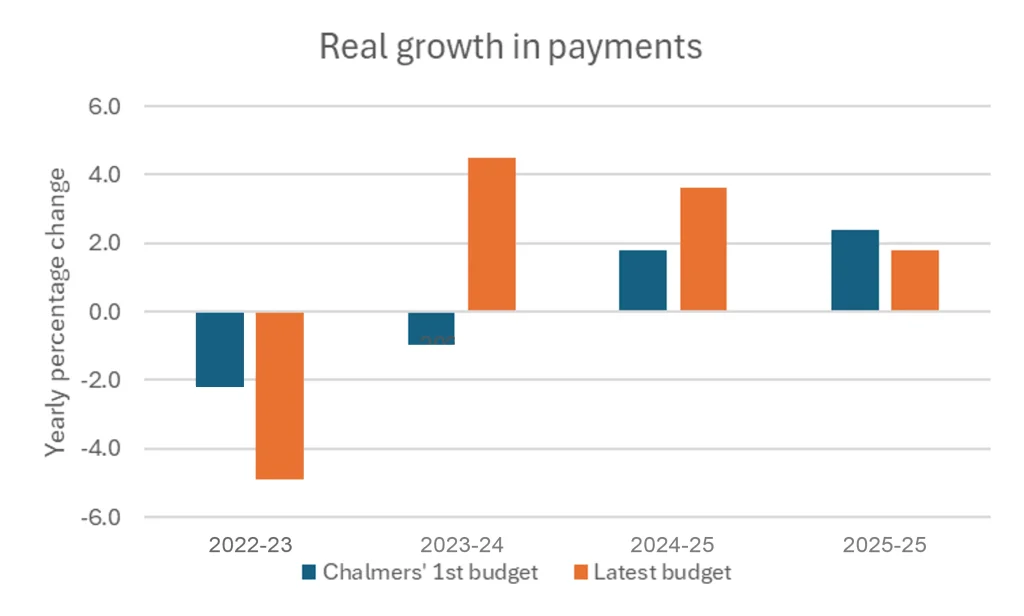

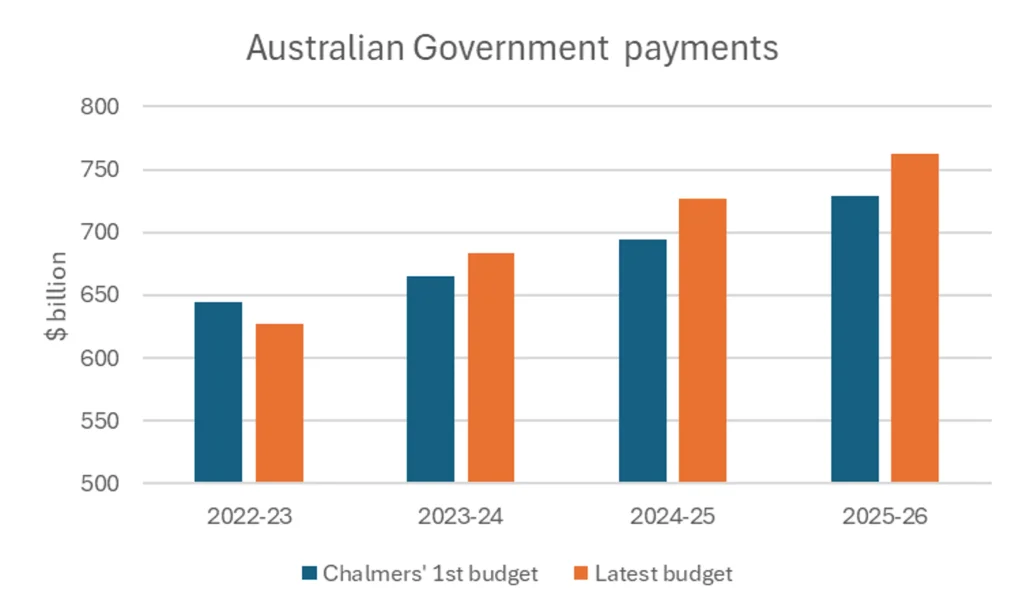

Alas, the government appears addicted to spending. In Chalmers’ first budget in October 2022, the Treasury estimated real growth of budget payments at -1% in 2023-24 (i.e. Treasury expected them to fall) and +1.8% in 2024-25. In the current budget, those figures have become +4.5 and +3.6%, respectively.

Payments in 2024-25 are $33 billion higher than the projection for 2024-25 in Chalmers’ first budget, more than accounting for the deficit in 2024-25. This massive revision of spending estimates has happened in just over 18 months.

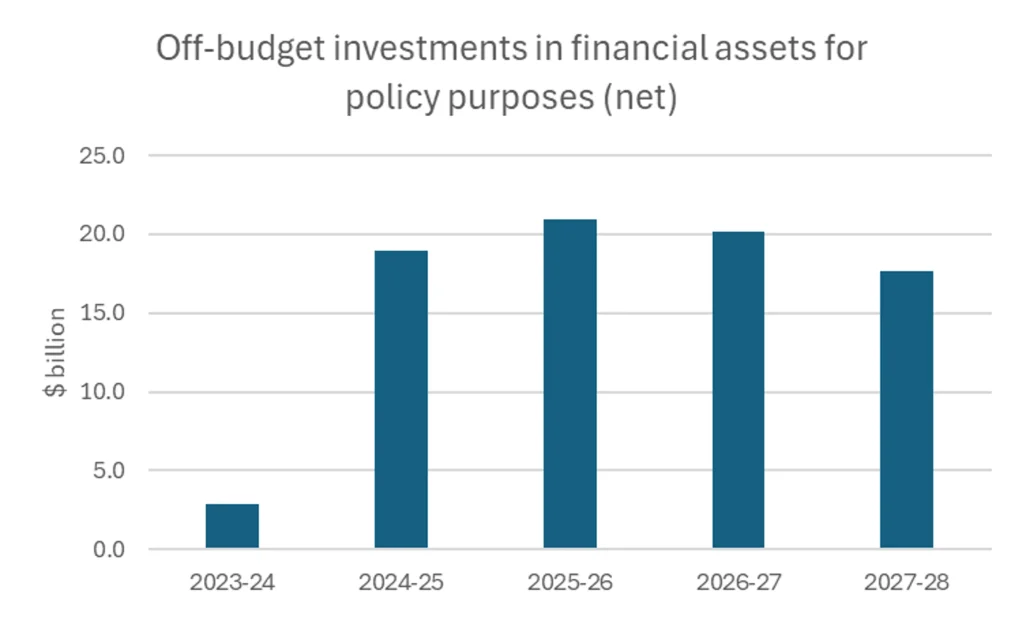

And the extra billions in off-budget spending are in addition to this figuring — $19 billion in 2024-25 and nearly $80 billion over four years.

The commencement of previously announced income tax cuts from 1 July will also stimulate demand, but they have been baked into the budget arithmetic for six years and the budget papers now concede that the tax cuts will do no more than offset three years’ bracket creep — and only in aggregate, not for every taxpayer.

Test 2: Strengthening federal finances

Amidst the buzz surrounding the 2023-24 surplus and the larger surplus in 2022-23, it is crucial to note that the government is estimating a 1% of GDP deficit in 2024-25, the financial year the latest budget is for. The Treasury’s estimates of the cyclical and structural components of the budget balance tell us the surplus should have been twice as large in 2023-24, and the budget should be roughly in balance, with a slim surplus in 2024-25. Continuing structural deficits are estimated for later years.

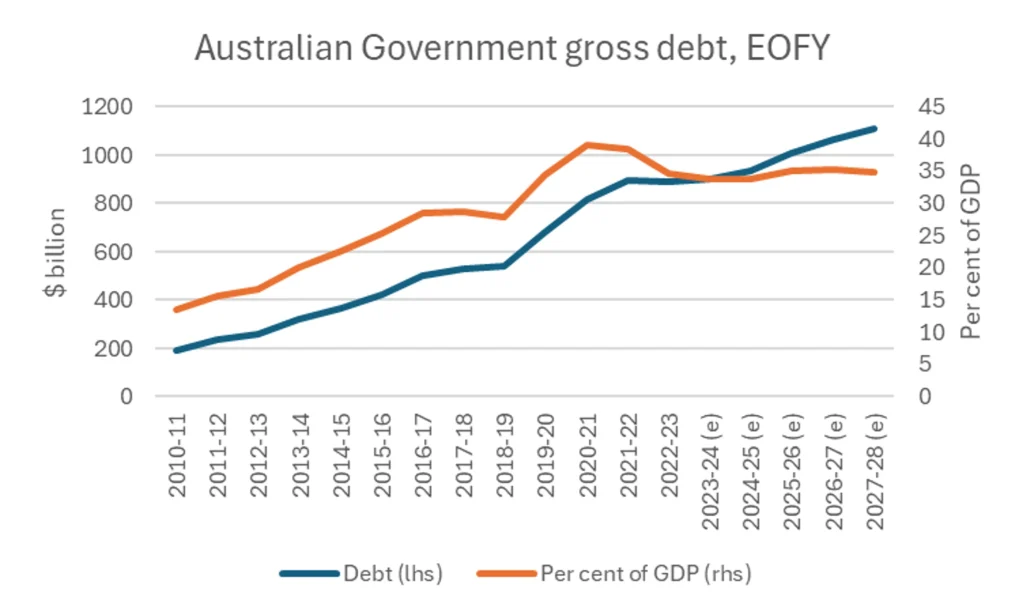

The most meaningful measure of federal debt — securities on issue at face value — has increased from $542 billion just before the pandemic to an estimated $900 billion now and levels exceeding $1,000 billion from 2025-26 onwards. As a percentage of GDP, this aggregate is supposed to peak at 35% and then edge down slightly.

While this stabilisation of the debt burden would provide some reassurance, it is important to observe that it is contingent on the government’s ability to curb its spending. The spending outcomes described above make a mockery of the projected slowdown in spending growth after 2024-25. It likely will not happen — there will be more spending, bigger deficits and more debt.

Test 3: Productivity

Strengthening productivity growth is critical to our future prosperity. While the budget is fundamentally a fiscal policy document, there are fiscal measures that can help promote productivity growth. Some of the measures in this budget do touch on productivity, but it is not listed among the many priorities of the budget.

Indeed, some of these priority actions may even send productivity backwards in the longer term. In its ‘Future Made in Australia’ initiative, the government has embraced what London School of Economics economist Mariana Mazzucato calls the ‘mission economy.’ The government sees its role as being to set the mission for an economy and to develop policies that guide the economy in achieving that mission. Our government sees its mission as shepherding Australia towards net zero emissions, guided by activist industrial policy favouring critical minerals processing and green hydrogen production. It is picking winners and showering billions of dollars of tax credits on selected recipients.

It is not precisely Soviet-style central planning but is a return to the era of highly interventionist democratic governments of the post-war period. It rejects the Hawke-Keating legacy: ending post-war protectionism and deregulating large parts of the economy. Hawke and Keating’s embrace of market economics in the 1980s, supported by Opposition members and John Howard in particular, set Australia up for one of its best-ever periods of economic performance following the early 1990s recession. From the bottom third of the OECD, we recovered to the top third by the mid-2000s, mainly through better policy settings. Globally, the greater embrace of free markets has seen an enormous reduction in extreme poverty–over one billion people since 1990.

The market-oriented approach started by Hawke-Keating helped boost productivity growth. It is doubtful that the mission-economy approach of Albanese-Chalmers will do the same, and may even send productivity backwards if the economy’s resources are misallocated to sub-optimal uses.

Activist industrial policy has chalked up numerous failures in history, including a domestic car industry that ultimately was unviable despite decades of tariff protection and billions of assistance. With his embrace of activist industrial policy, Chalmers is ignoring history lessons, both here and overseas.

Test 4: National security and social issues

The government will say that some of its Made in Australia measures will strengthen national security, but this rests more on the defence budget than on anything else. There are two aspects to this: how much is being spent on defence; and how effectively is it spent. On the ‘how much’, the budget boasts of a 14.8% increase, but this is heavily backloaded to 2027-28; presumably so as not to upset the more immediate budget numbers too much. Meanwhile, the bang-for-the-buck of defence spending has been subject to some scathing reviews and the best that can be said about this aspect is that it is a work in progress.

On the social side, the budget correctly identifies the cost and availability of housing as the major issue of the day. The government and Treasury seem to clearly recognise the need to build more housing as the solution. However, this is not supported by meaningful action. The centrepieces of the government’s so-called ‘ambitious’ housing policy are the Housing Australia Future Fund, delivering 30,000 dwellings, and the Help to Buy scheme, delivering 10,000 dwellings. These contributions amount to no more than a rounding error on National Cabinet’s target of 1.2 million homes. As this target looks increasingly difficult to achieve, the government is buck-passing, saying it is the responsibility of the states.

Conclusions

Returning to the key tests set out in the beginning, the budget can be assessed as follows.

- Does it contribute as much as it can to the effort to bring inflation down in a sustainable fashion and in so doing effectively address the cost of living ‘crisis’? No. Instead it provides some short-term relief that possibly adds to inflationary pressures and which will be reversed when the assistance comes to an end.

- Does it stabilise and strengthen the government’s financial position after the upheavals of the pandemic period? No. By adding to federal debt unnecessarily, it worsens it, and the projected stabilisation of the debt is not credible given the government’s track record on spending.

- Does it help end the long period of productivity stagnation — surely the key to a resumption of growth in real wage? No. It is a rejection of the Hawke-Keating legacy of sound economic policy and an embrace of activist industrial policy, a policy which has failed time and time again around the world.

- Does it answer the national security and major social issues of the times, particularly the high cost of housing? While recognising the urgency of the housing crisis, it does little to expand the housing supply that is crucially need.

In other words, the 2024-25 federal budget fails all the important policy tests and is not in the long-term interests of Australians.