Introduction

A number of recent events, including most notably the plebiscite on same sex marriage in 2017 and the Voice referendum in 2023, have shone a light on the extent to which large Australian corporations are taking a more active role in society’s social and political debates.

This increase in corporate activity is not happening in a vacuum. In fact, it can be seen as part of a broader potential change in the nature of corporations and their role in society.

Historically, the prevailing view was that the primary role of the corporation was to maximise returns for shareholders. While it would be a caricature to say this was the only consideration for those running a business — most businesses would accept they had a responsibility to their employees, for example — it was expected that the shareholders were central to the activities of the business.

Over time, there have been a number of challenges to this view.

One prominent issue that has become increasingly prevalent as companies have become larger, and the number of shareholders has expanded significantly, is the agency problem. This arises from the large separation between the company owners and its management. The management, although they are appointed as agents to act in the best interests of the shareholders, are also personally affected by the decisions made by the company. Actions taken in accordance with their duties may conflict with their personal benefit or interests.

While an obvious example is a potential conflict between maximising management salaries and perks vs returning extra dividends to shareholders, there are also more subtle examples. It might be in the interest of a CEO of a large corporation to undertake a major project because of the prestige associated with managing it, even if the financial returns may be better elsewhere.

Or, perhaps more relevantly to the issue of corporate activism, a CEO might wield the financial resources they can command through their employer company to promote social causes they believe in or oppose those causes they disagree with. Such advocacy may be against the personal attitudes and preferences of shareholders, or otherwise not to their financial benefit.

Agency issues are not the only challenge to shareholder primacy. Another challenge comes from a changing conception of who a company owes duties to. According to this perspective, the duty a company owes its shareholders is no longer singular, possibly not even its primary obligation. This is replaced instead by a duty to a broad range of ‘stakeholders’ — which might include employees and customers or even government, labour unions, the environment or society at large.

Although it is perhaps not strictly the same thing, this viewpoint could also be viewed alongside the idea of ‘social licence’, which is the idea that in order to operate within a community, a company must maintain the trust and support of that community. Companies that break the ‘unwritten rules’ could be sanctioned, boycotted or, in more extreme formulations, subject to borderline punitive taxes and regulations.

Another agenda related to, or even perhaps the same as, this is emergence of the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) framework and movement, the most recent mutation of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

ESG reporting is becoming increasingly common for public companies around the world, including in Australia. Much of the focus of ESG efforts is external to the business, relating to how it operates within the community, while the other often used acronym, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI), more often refers to the internal operations of a company including who it employs and how it attracts those staff members. There remains considerable overlap and little precision about these initiatives; although an increasingly substantial bureaucracy is emerging within Australia and globally seeking to normalise reporting on these initiatives as well as mandating certain disclosures against ESG or DEI benchmarks.

Indeed, Australia is far from alone in seeing corporations moving away from viewing the interests of shareholders as the central goal. As can be seen in response to the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States for example, or trans-rights issues in the UK and US, corporate activism is a global issue. As Jeremy Sammut reported in his 2018 paper on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), “the business of business will not just be CSR in the best interests of the business: the business of business will be politics.”

One potential driver for this changing view is a supposed prominence of support for the corporate social licence / ESG view among younger generations. Another potential motivating factor is a shift leftwards of the management of major corporations, largely aligning with voting patterns of university graduates (who are trending strongly left in many countries).

However, it is far from clear that shareholders approve of this dilution of their interests.

This report presents the findings of polling conducted by Redbridge between 10 and 22 April 2024. More details on the polling can be found in Appendix A. Unlike previous polling, the point of this report is not to ask whether those polled support specific initiatives such as the Indigenous Voice.

Instead, these polls test the knowledge and understanding among three groups (shareholders, employees, and customers) of corporate activity across three domains (charitable donations, social activism, and political donations).

Finally, by applying a generational lens to the results it is also possible to test whether different generations do in fact have material differences in how they view the role of corporations in society.

Awareness & Alignment

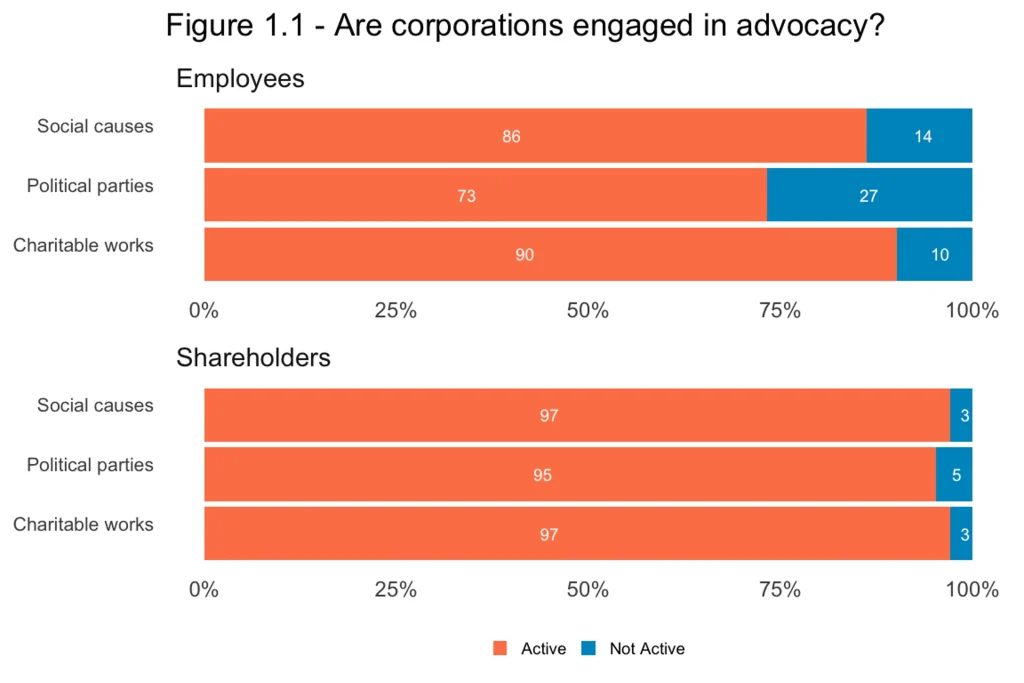

A preliminary question worth confirming is that a substantial proportion of companies within the sample are in fact engaged in charity work, corporate activism, and political donations.

Our samples show, once those who are unsure whether the companies are engaged in these activities are removed, that the overwhelming majority of people believe the companies they are associated with are involved in some capacity.

Two interesting findings emerge. The first is that companies appear to be less likely to make political donations than they are to either undertake charitable works or engage in social activism.

One possible explanation for this is that political donations in Australia are subject to regulatory restrictions on who can give what and when, as well as significant transparency requirements. Some jurisdictions prohibit donations from certain types of businesses (such as property developers and others in NSW).

It’s also possible there is a growing scepticism about the effectiveness of political donations. As society becomes more polarised, political donations may come with reputational risks that end up harming businesses more than helping them. Further, political donations can be seen by stakeholders, including customers, as a means of purchasing influence in future government —a strategy looked poorly upon by most Australians.

The other point of note is that shareholders reported a far greater percentage of the companies they hold shares in are active in each of the three categories. It’s possible this is simply natural variance in the sample: it was not feasible to match the shareholding sample and the employees sample by company. Another possible reason is that the shareholders sampled likely held shares in public companies, and larger companies were found to be more likely to engage in the activities in question.

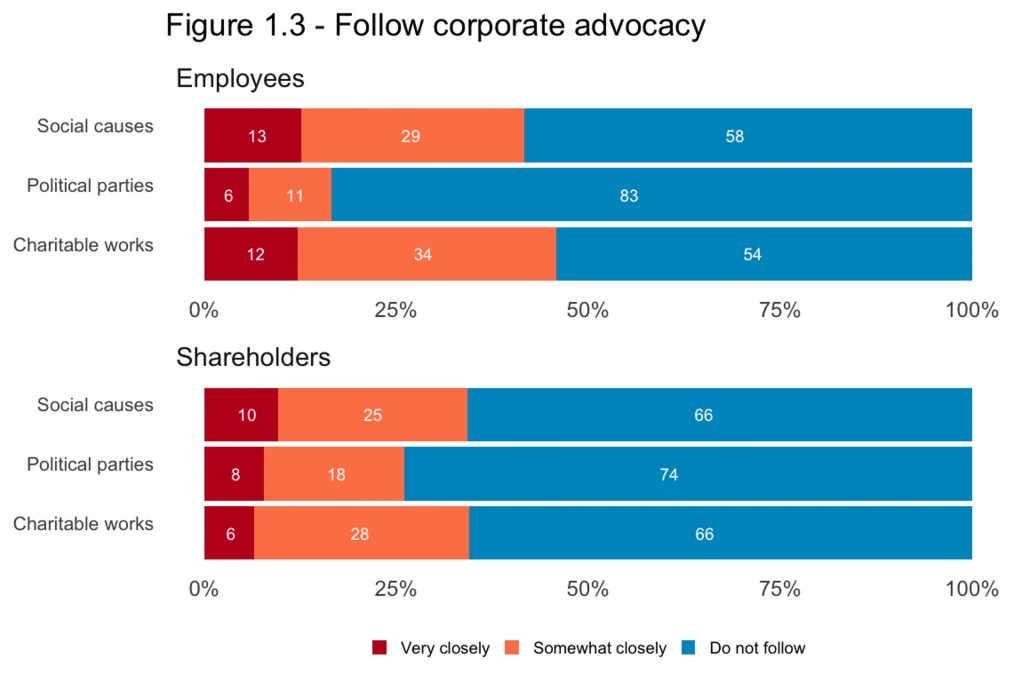

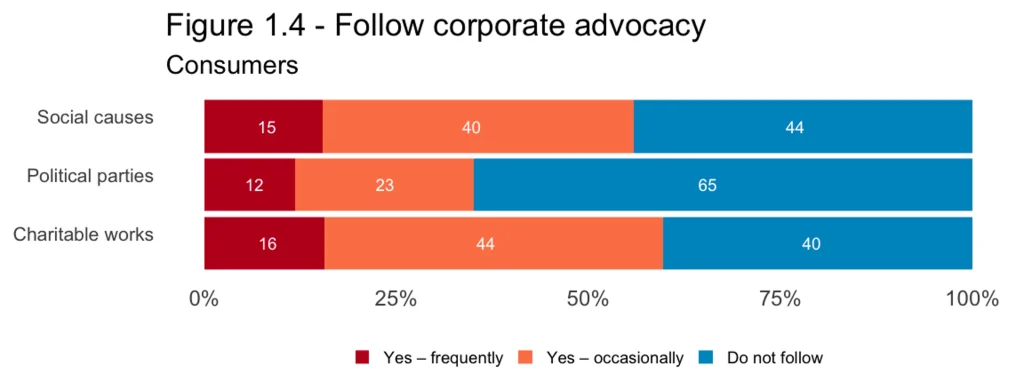

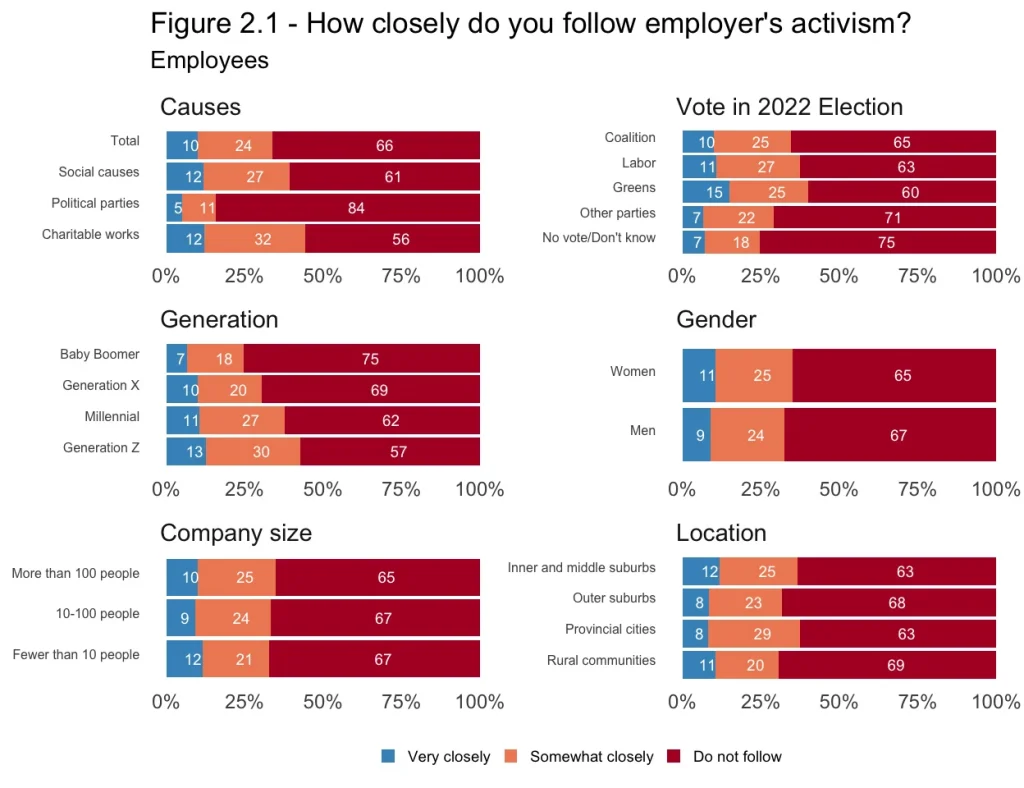

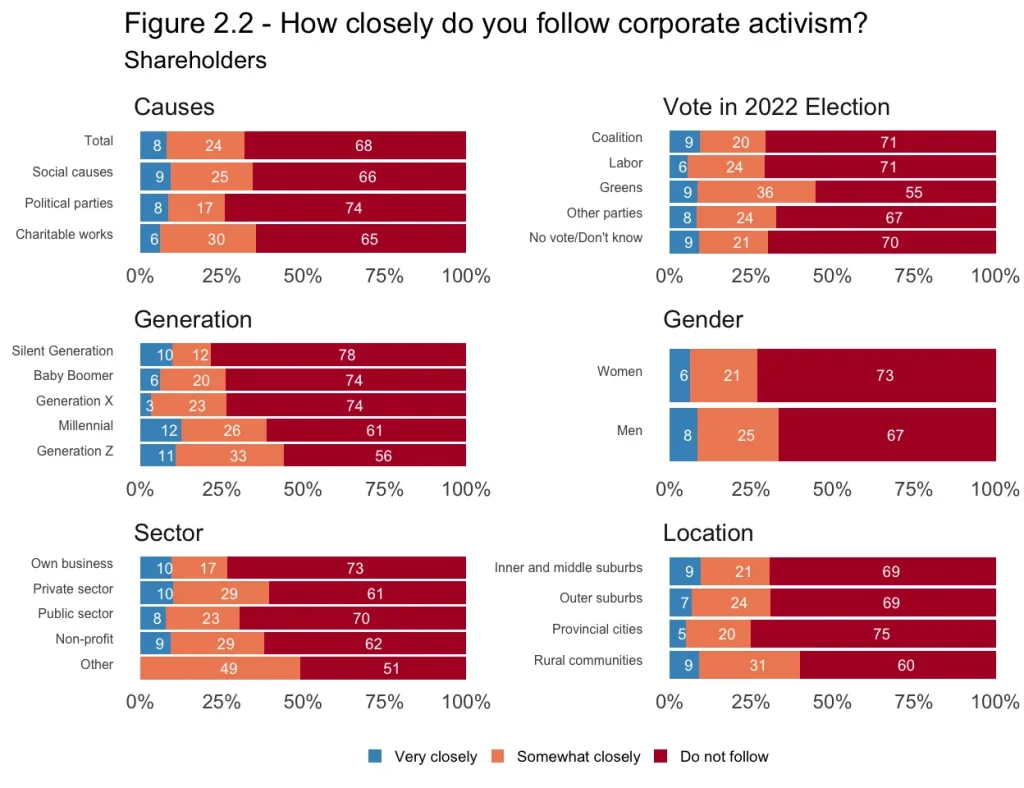

Neither shareholders nor employees closely follow the activism of their companies

One of the most important initial steps in understanding corporate activism is to track the extent to which the three groups identified in the survey are aware of the actions undertaken by the companies they are involved with.

A significant majority of both employees and shareholders report that they do not follow the relevant activities of their company at all.

Employees are slightly more likely to report following the activities of the companies they work at than shareholders report following companies they own shares in. This is unsurprising, given employees likely have a far greater engagement with the company on a day-to-day basis.

The fact that fewer than 15% of employees and shareholders report very closely following these activities is highly significant. It suggests that far from being a mass movement, driven from the ground up, the kind of initiatives being undertaken in these areas are considered peripheral — if not largely ignored — by most shareholders and employees.

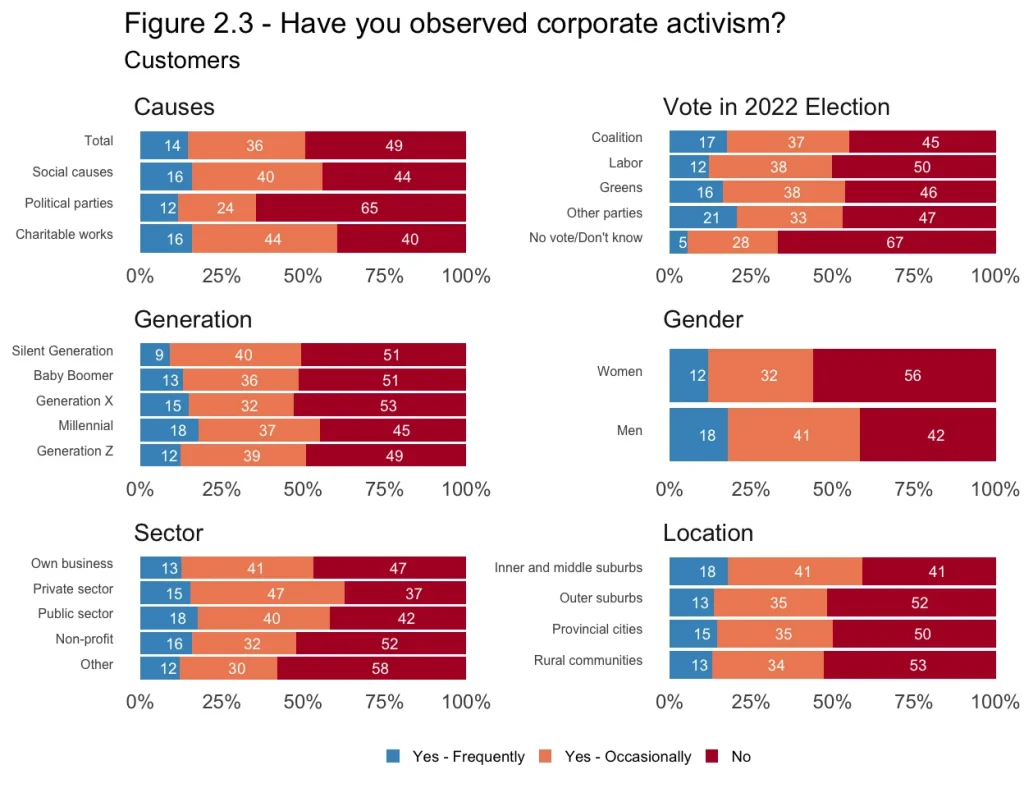

However, the story is different for consumers. Although it is still only a minority that report frequently following the activities of the companies they patronise, more report some awareness than no awareness.

BOX: Follow activism

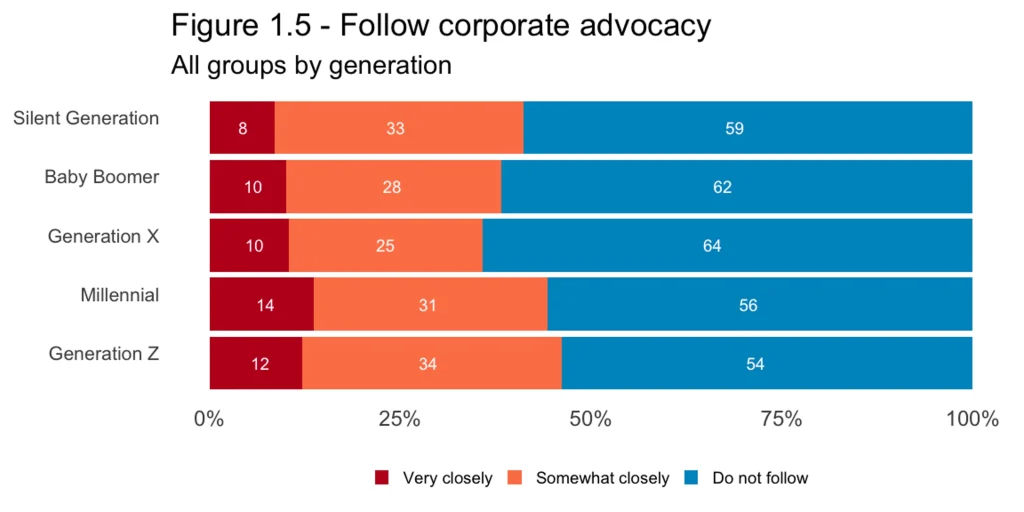

Generational breakdown

If we break our samples down by generation, we can see differences emerge between younger and older Australians. Millennials and Gen Zs are slightly more likely to pay attention to social activism than the preceding generations. This lends support to the theory that younger generations are involved in the increase in social activism.

However, the evidence that this variance is significant enough to drive change is fairly weak. Over half of all Millennials and Gen Zs still report not following corporate activism, compared 62% and 64% of Gen Xs and Baby Boomers. Only 12-14% percent report following these activities very closely, just a couple of percentage points above their older counterparts.

A more plausible possible explanation is that decision-makers, especially in larger companies, are likely to be older and so have less direct engagement with younger generations. Decision-makers may believe these initiatives appeal to a far larger percentage of younger shareholders and employees than they actually do. This could be reinforced by the possibility that those who are actively engaged in these issues may be ‘louder’ or more prominent than those who pay little or no attention.

The actions of companies do not align with their stakeholders particularly well

The next element to be considered is whether the companies’ advocacy and actions align with the preferences of their shareholders, employees, or customers.

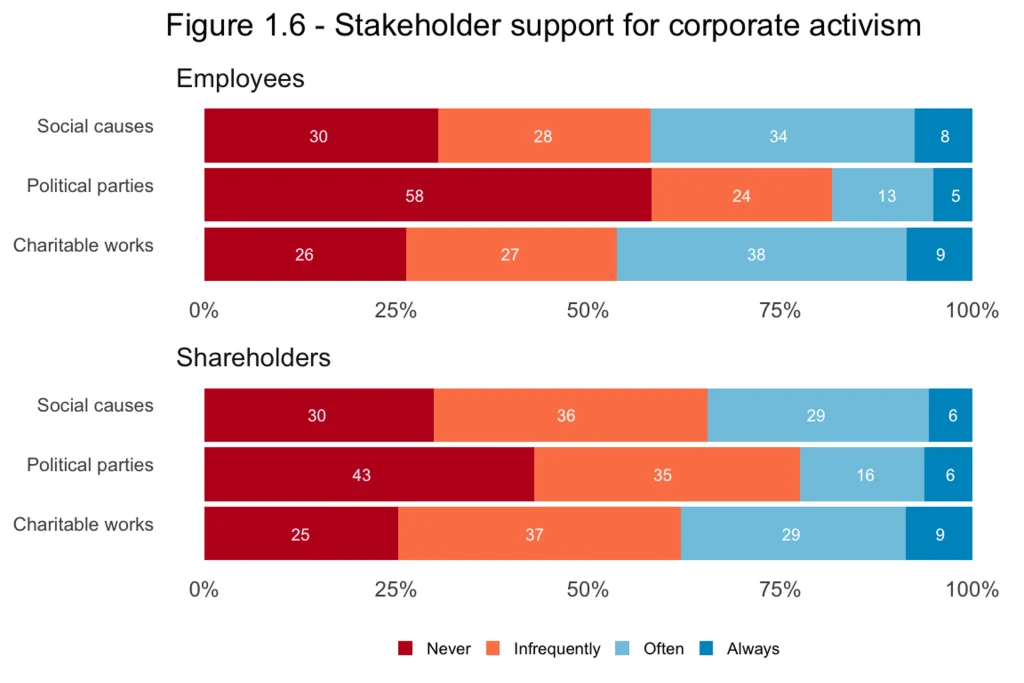

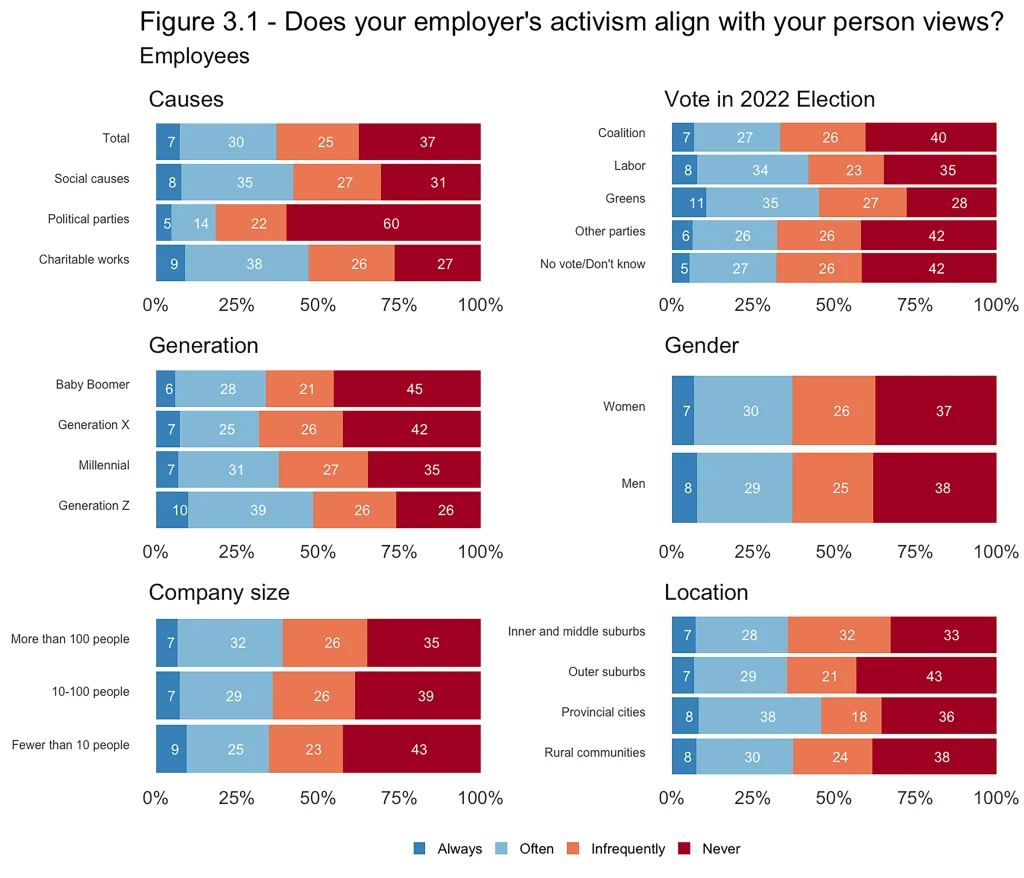

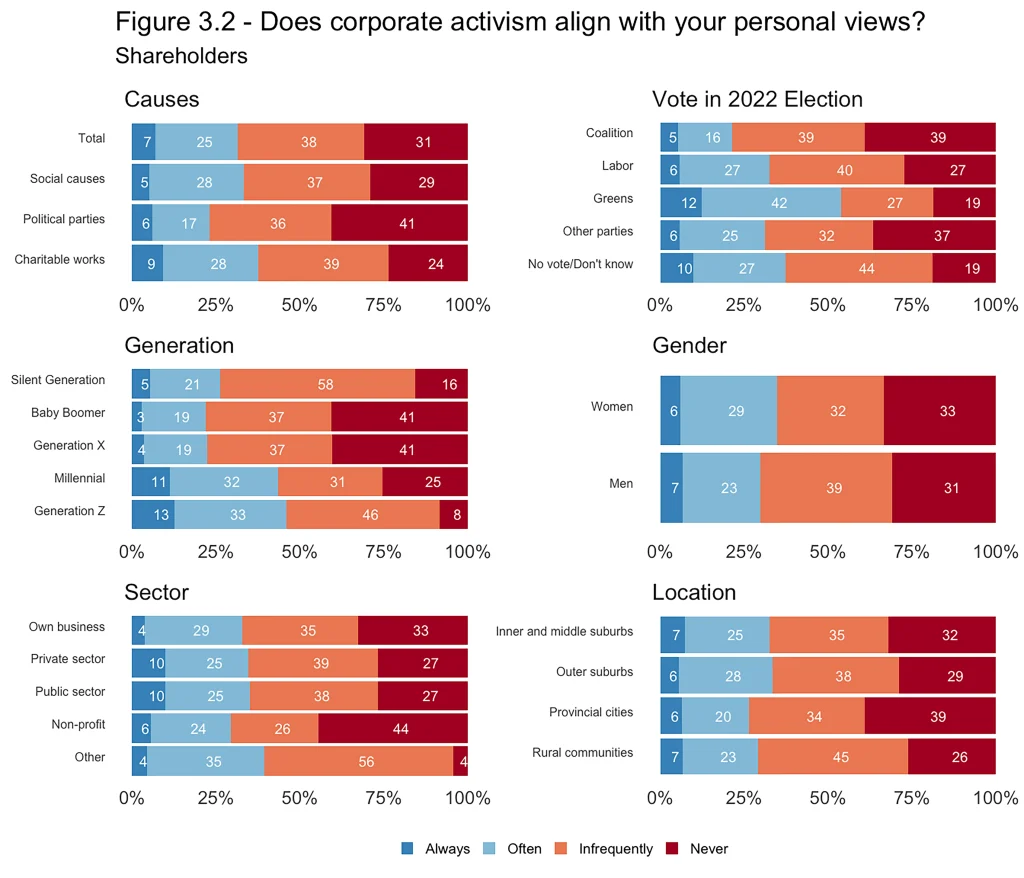

Here we see some surprising results. The majority of employees and shareholders sampled report that the views and actions of the companies they are associated with never, or infrequently, align with their own view.

Indeed, less than 10% of those who responded to this question reported they were always in alignment with the companies’ actions and advocacy. When it comes to political parties, more than 80% of employees, and nearly 80% of shareholders, reported a lack of alignment.

When it comes to social causes and charity, although both groups report an overall lack of alignment, the minority of employees that report they ‘often’ align with the company is slightly larger than the shareholder sample. Shareholders are more likely to respond they align ‘infrequently’.

The difference seems to be that, among those who are sometimes in alignment with the position taken by companies, employees are more likely to be aligned ‘often’ and shareholders are only likely to be aligned ‘infrequently’. This is the opposite of what you might predict if companies were managing their agency concerns more effectively.

One possible explanation for this is that the employee sample is overall slightly younger (reflecting the likely disparity in wealth between younger and older generations). As noted below, younger generations do report greater alignment overall.

However, the theme that emerges from both these questions is that when it comes to corporate activism, most workers don’t know about it, and do not support it when they do know.

BOX: Support activism by generation

Generational breakdown

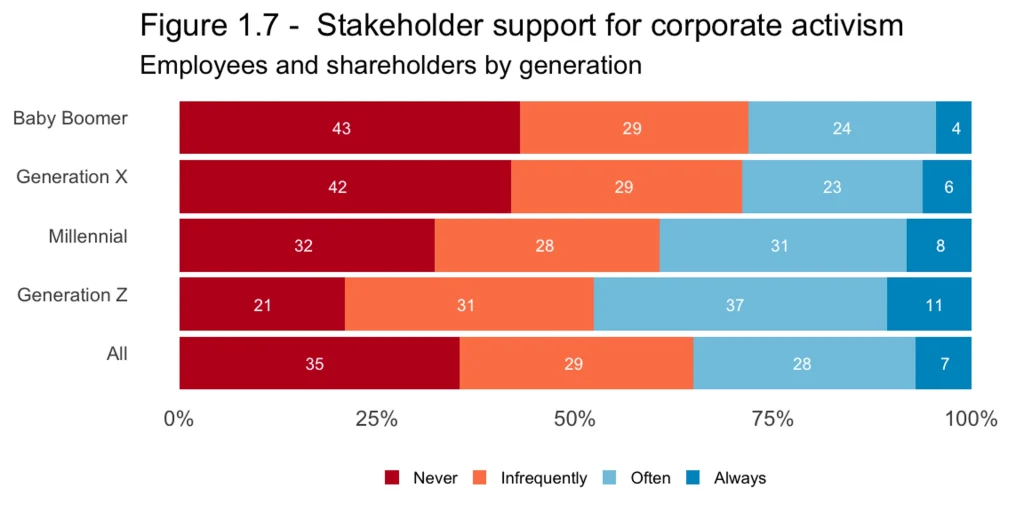

We see a significant variance in reported alignment with corporate activity by generation.

In fact, nearly half of Generation Z respondents reported a generally positive alignment with corporate activism. That said, it is worth noting only 11% reported they always agreed with corporate activism; quite a small percentage. Meanwhile, nearly twice as many Gen Zs reported they were never aligned. The overall position remains one of misalignment with the positioning taken by companies. It’s a matter of degree.

What is interesting is that Baby Boomers and Gen Xs had particularly high response rates of ‘never’, while Millennials had broadly similar numbers responding ‘never’, ‘infrequently’ and ‘often’. The number of those responding ‘infrequently’ were similar across all groups. Overall, the middle (those who align ‘infrequently’ or ‘often’) is split roughly in half. However, the poles of the distribution are deeply unbalanced. More than a third of overall respondents ‘never’ align, just 7% ‘always’ align.

This suggests that, to the extent there are sizeable groups in opposition to each other, one is a core group, predominately made up of Boomers and Gen X, that are strongly out of alignment with the direction of corporate advocacy. The opposing group, led by Millennials and Gen Z, is broadly in alignment, but not as strongly aligned as those in opposition are misaligned. The group that is strongly aligned is quite small.

Overall, the responses to the questions in this section suggest corporate activism is strongly supported by, and perhaps targeted at, a relatively small group of individuals. Less than 10% of employees and shareholders, disproportionately younger individuals, strongly support initiatives the majority of companies are engaged in.

The majority, silent or otherwise, certainly have little to no awareness of what is being done (arguably in their name) and to the extent they are aware, comparatively few agree with it.

It is worth noting in passing that even were the actions of these companies more closely aligned with the reported preferences of these groups, it does not necessarily mean companies should engage in those actions.

For example, a company that wished to give a significant donation to an activist campaign could provide a special dividend to its shareholders and recommend they support this activism, and could create workplace giving options for employees.

It could also poll its workers, shareholders, and customers to at least see if the proposed action aligns with the views of the stakeholders.

Of course, from the point of view of an activist manager convinced of the merits of a given ESG initiative, these actions might be undesirable. On these results, at best they risk being ignored, at worst they might be discouraged from doing what they want with shareholder funds.

Behavioural change

The response of stakeholders to this activism should be important to the interests of companies. With most stakeholders disagreeing with corporate activism when they become aware of it, companies risk driving away employees and investors. Worse for the interest of activist companies, the generational trends mean the stakeholders least likely to support these initiatives are those with the most experience to provide their employer and available funds to invest.

However, if those stakeholders choose to ignore the activism and do not take action in response to it, corporations don’t risk serious negative consequences from these initiatives, at least in the short term. However, as the architect in the movie The Matrix reloaded once observed, a minority if left unchecked can reflect an escalating probability of disaster. A steady flow of disaffected shareholders and employees leaving the organisation over time represents a significant issue.

On the other hand, if the minority who are aware and are in support are much more likely to respond and do so positively, management may decide these initiatives are valuable regardless of any lack in broad support.

Additionally, if those in favour of pushing the agenda within the company are able to identify a subset of shareholders, employees and consumers who respond positively and take action, they can misrepresent the support of this group as reflecting a broader level of community support. Alternatively, they may claim, with perhaps more justification, that this represents support from some and ambivalence from others.

Partisan political activism drives away employees and shareholders

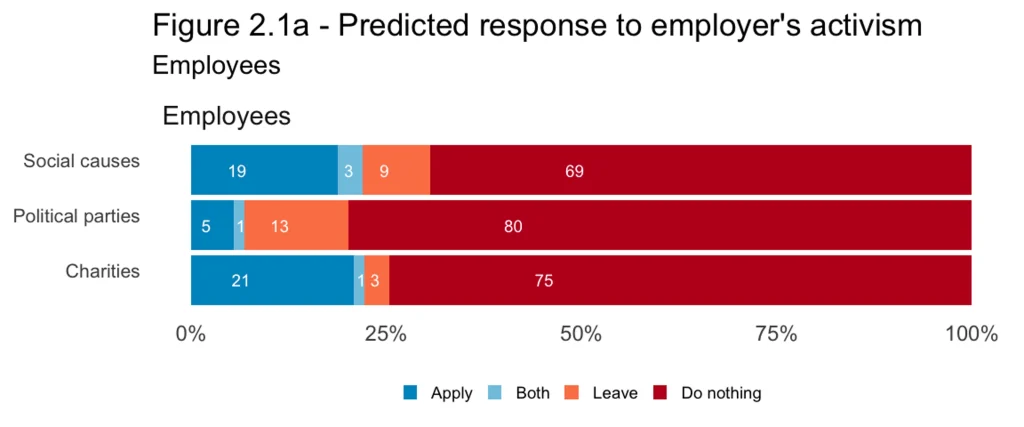

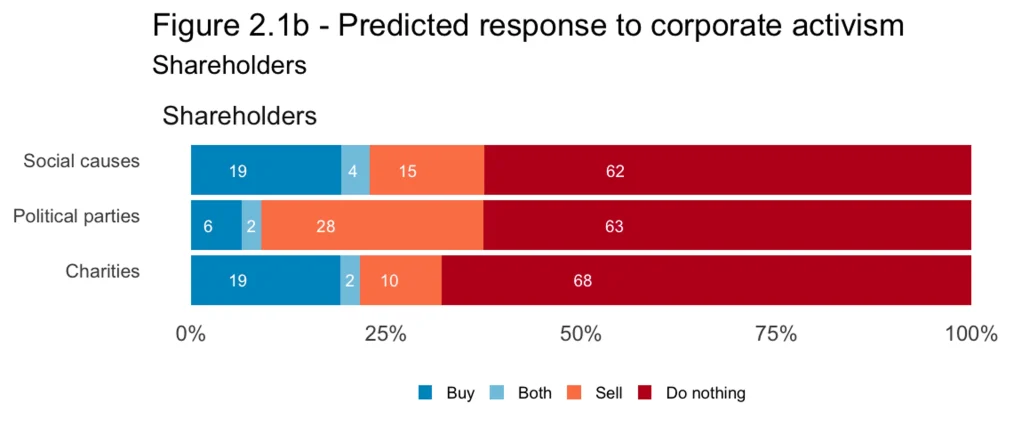

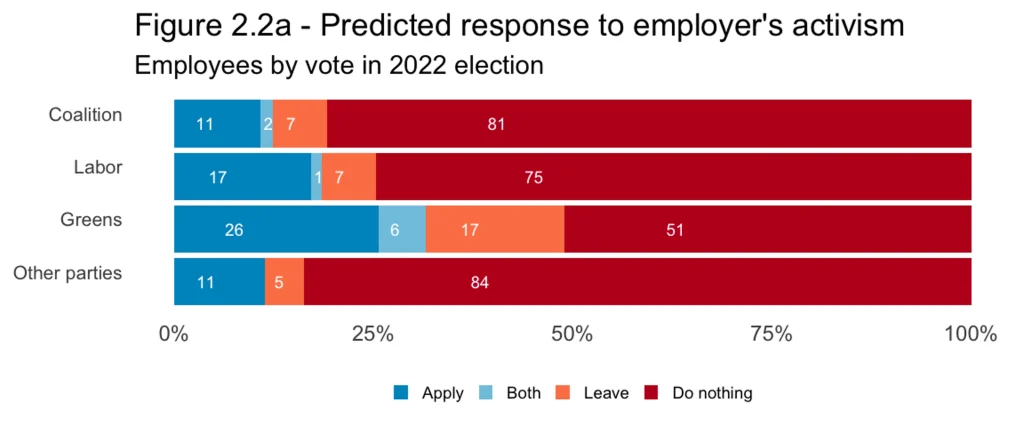

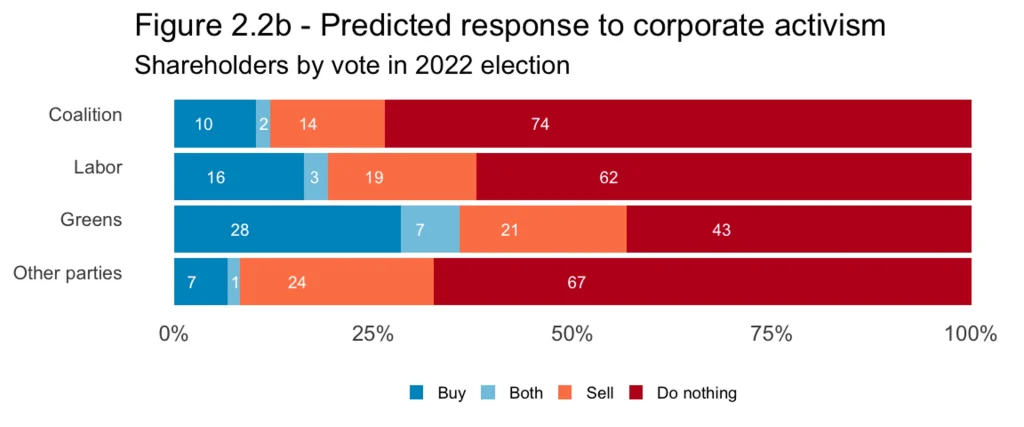

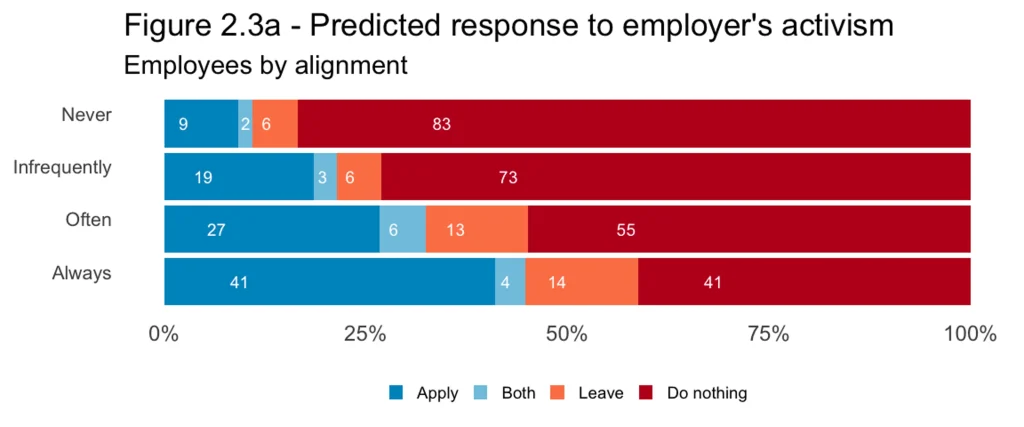

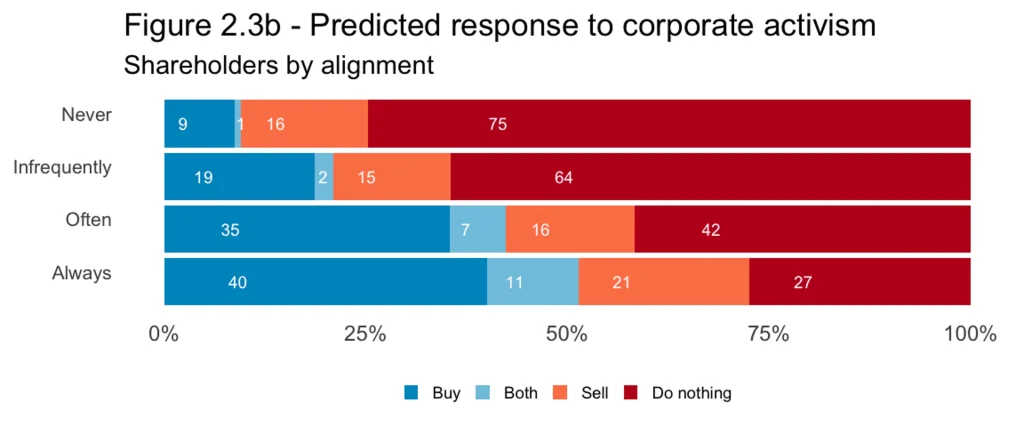

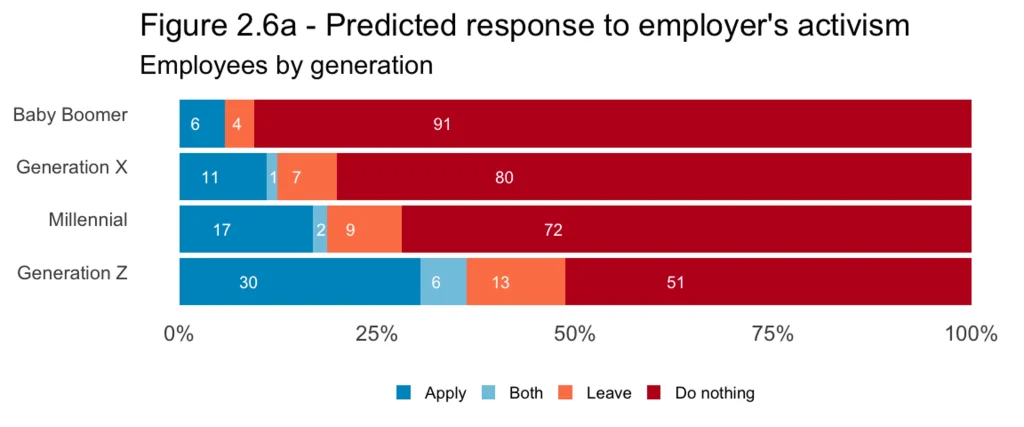

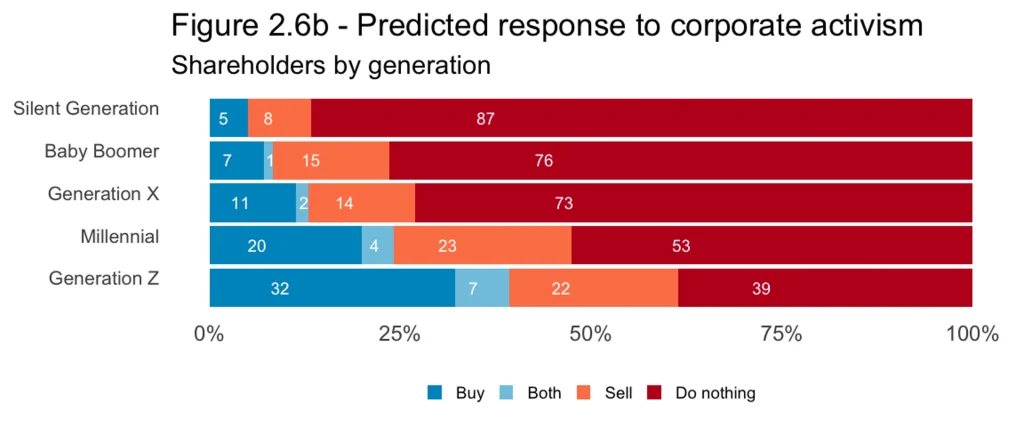

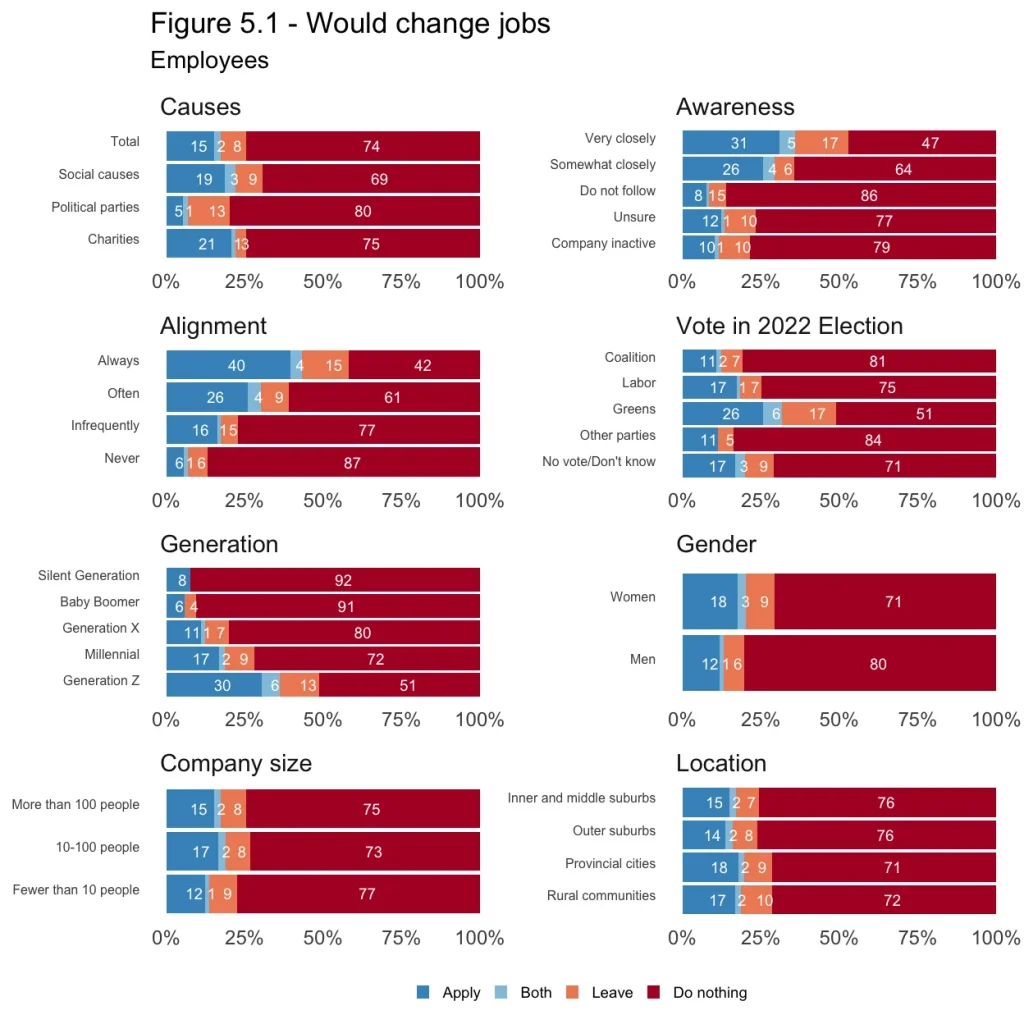

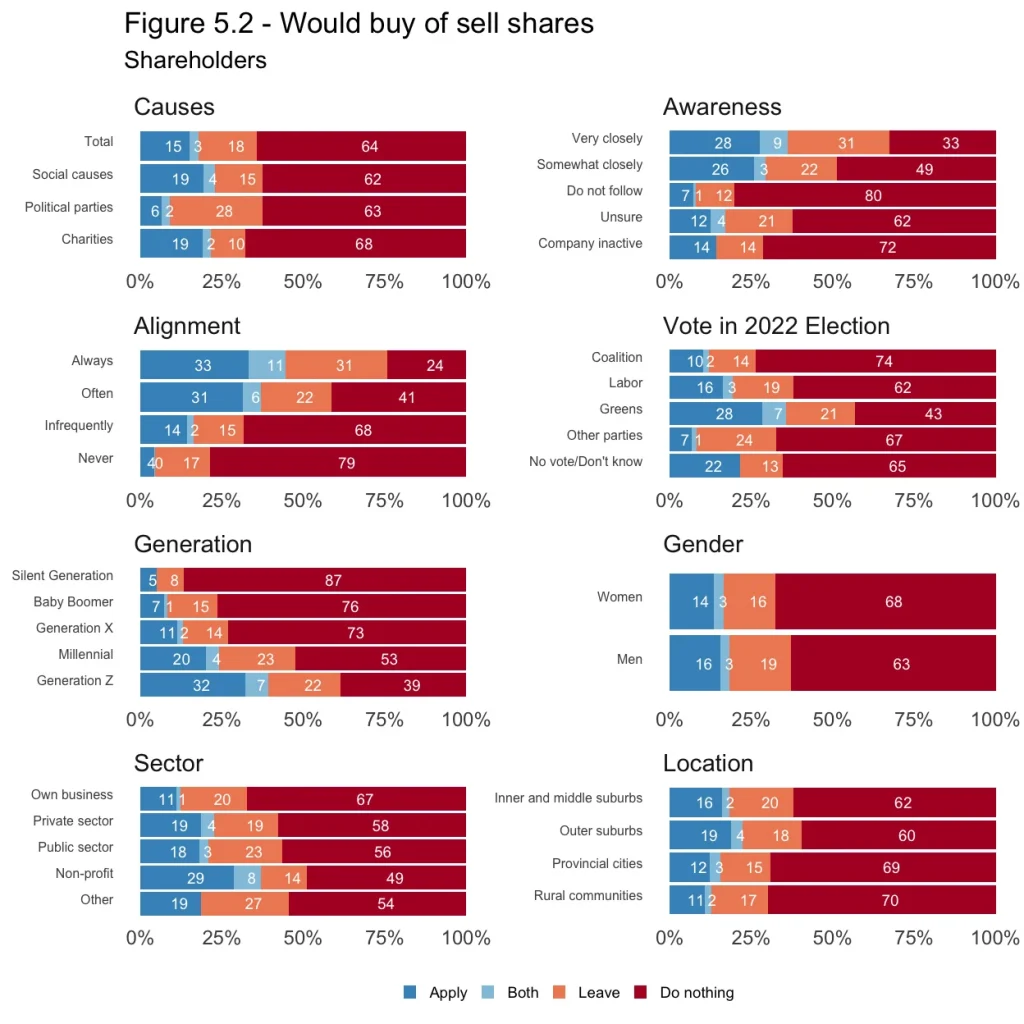

We asked stakeholders how they expected they would respond to activism at their company or the companies where they hold shares.

Employees reported they are more likely to leave a job than apply for one because of political donations made by the company and shareholders are more likely to sell than buy shares. However, the opposite holds true for social activism and charitable works.

This would indicate that those attracted to these initiatives are more likely to act than those opposed. Of course, it should also be noted that corporations would be wise to focus on purely charitable works, because more people are likely to take positive action and fewer likely to take negative action, than take positions on more controversial and politically-charged issues.

Indeed, one interpretation of these results is that the same action by a company in supporting a cause could see those joining the company / buying the shares almost completely offset by those leaving the company / selling the shares.

Shareholders are, unsurprisingly, more sensitive to corporate advocacy than employees. This likely is because there is much less friction in the decision to buy or sell shares than there is when choosing to apply for or leave a job.

However, the bigger point is that those willing to take any action in response to these initiatives is only a minority. As something that ‘moves the needle’ ESG initiatives seem like they might be a poor choice.

There is only one group where a majority of respondents indicated they would take action in response to a business’s activism: those who voted for the Greens in the 2022 election. The sensitivity of Greens voters to corporate activism may in part explain the leftward bent these initiatives tend to take.

That said, even among Greens voters, approximately only one in three say they would apply for roles or buy shares because of a company’s activism. Meanwhile, nearly a quarter say they would leave because of a company’s activism and nearly a third would sell shares because of it.

Labor, Coalition and other voters are significantly less likely to say they will take action based on a company’s activism.

The 7% of stakeholders who report they are always in alignment with corporate activism are the only group where more than half of shareholders buy shares based on activism. Even among the most supportive followers of activism, less than half say they would apply for jobs in response to these initiatives.

This remains a very small proportion of the broader population, suggesting corporations are risking alienating a majority of stakeholders in order to attract a small minority.

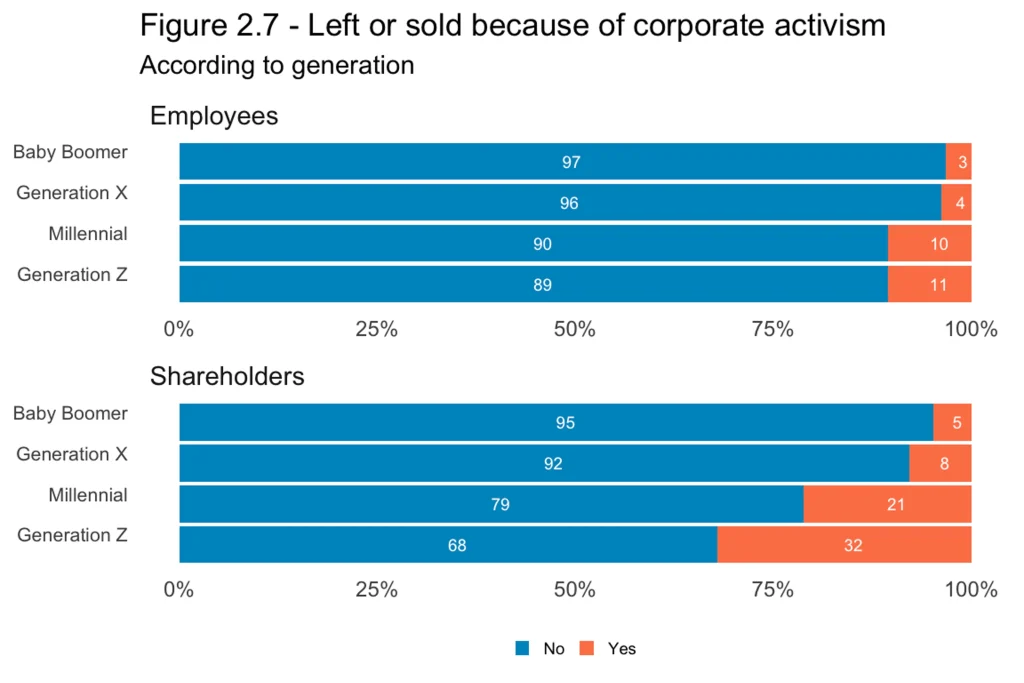

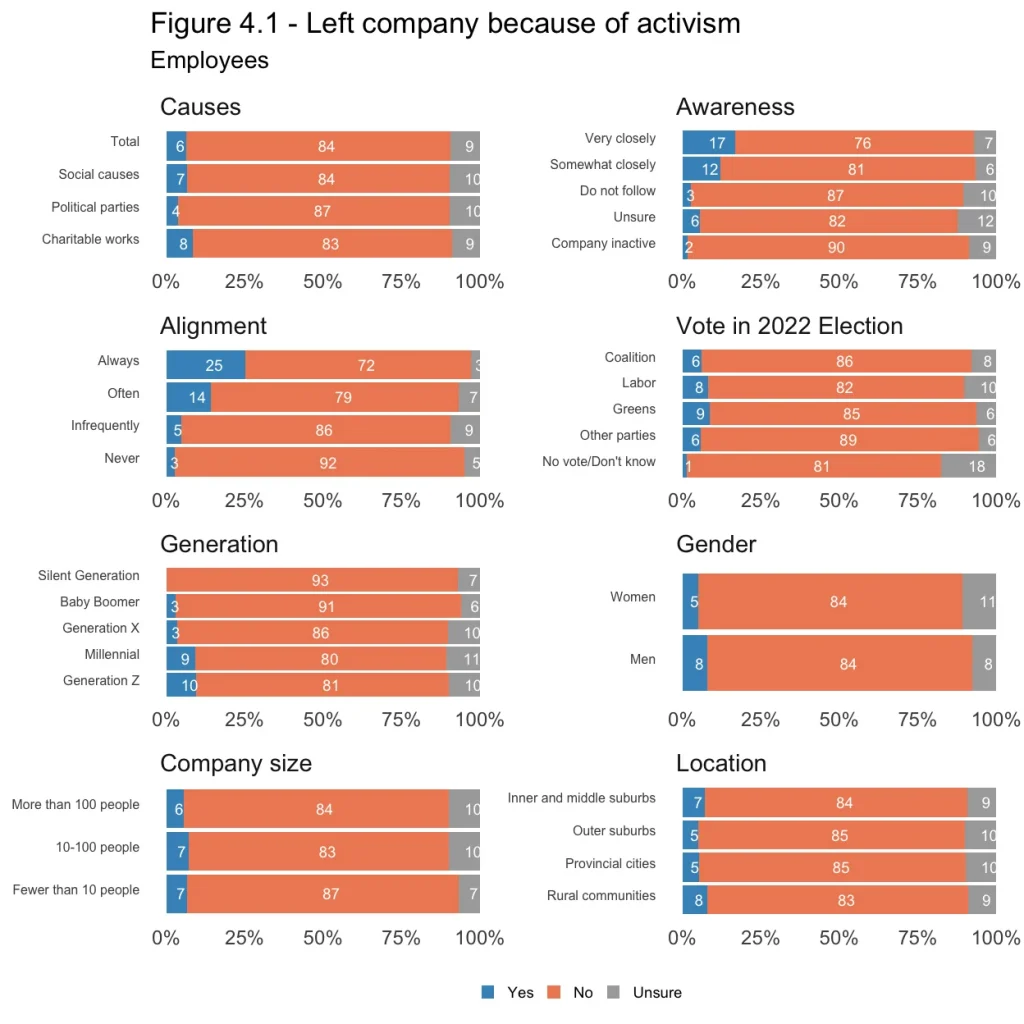

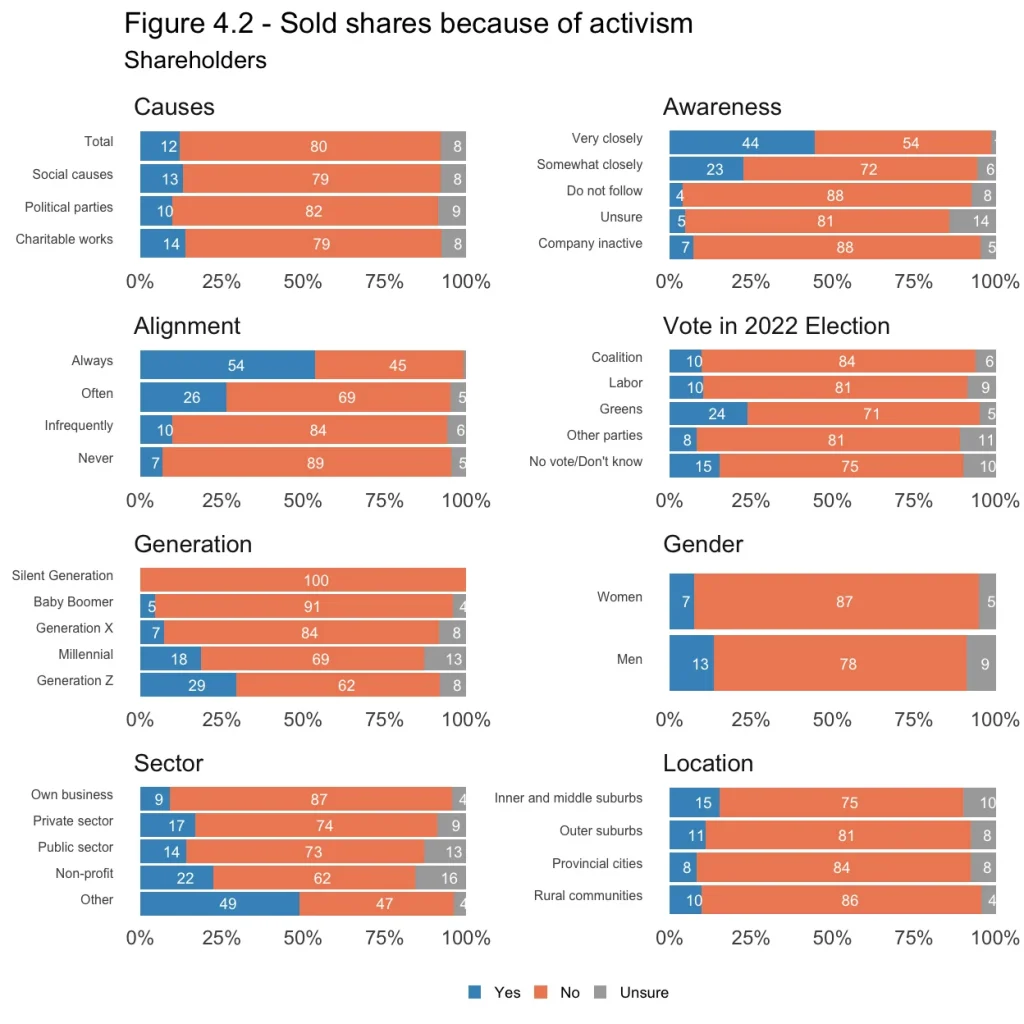

Nearly 1 in 10 have left a job or sold shares because of corporate activism

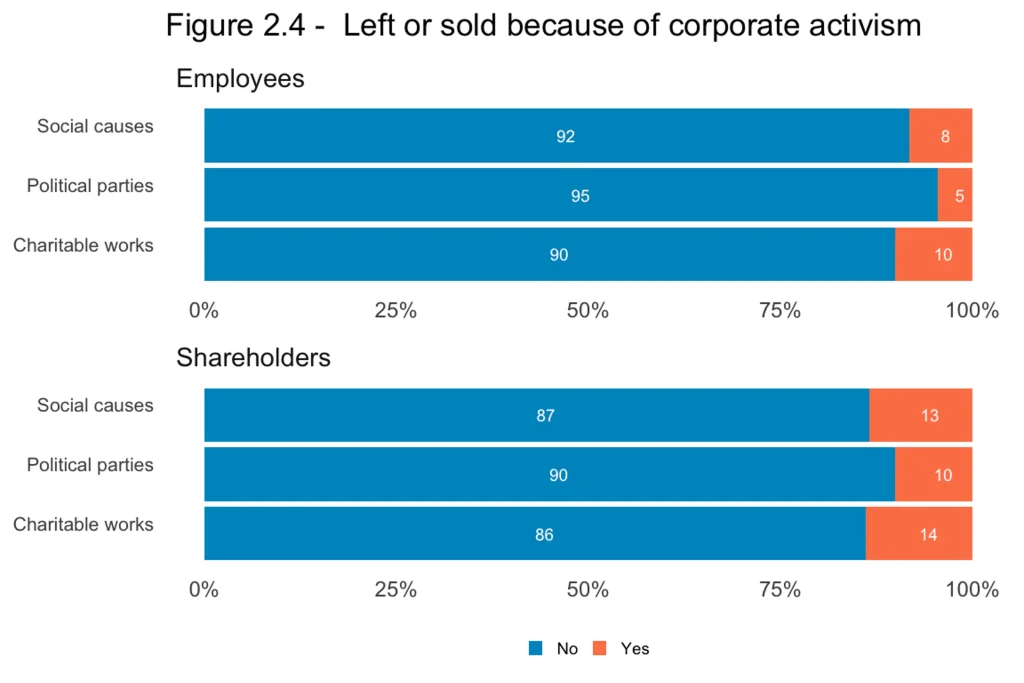

That said, how people say they will respond often differs from the actual actions they choose to take. When asked whether they have left a role or sold shares because of a company’s activism, 8% of employees said they have chosen to leave a company because of social activism, 5% because of political activism and 10% because of charitable works. The trend for shareholders is similar, with 13% selling because of social activism, 10% because of political activism and 14% because of charitable works and donations.

This breakdown undoubtedly reflects the level of awareness about each area of corporate activism. Shareholders and employees are most aware of charitable works and least aware of companies’ political donations.

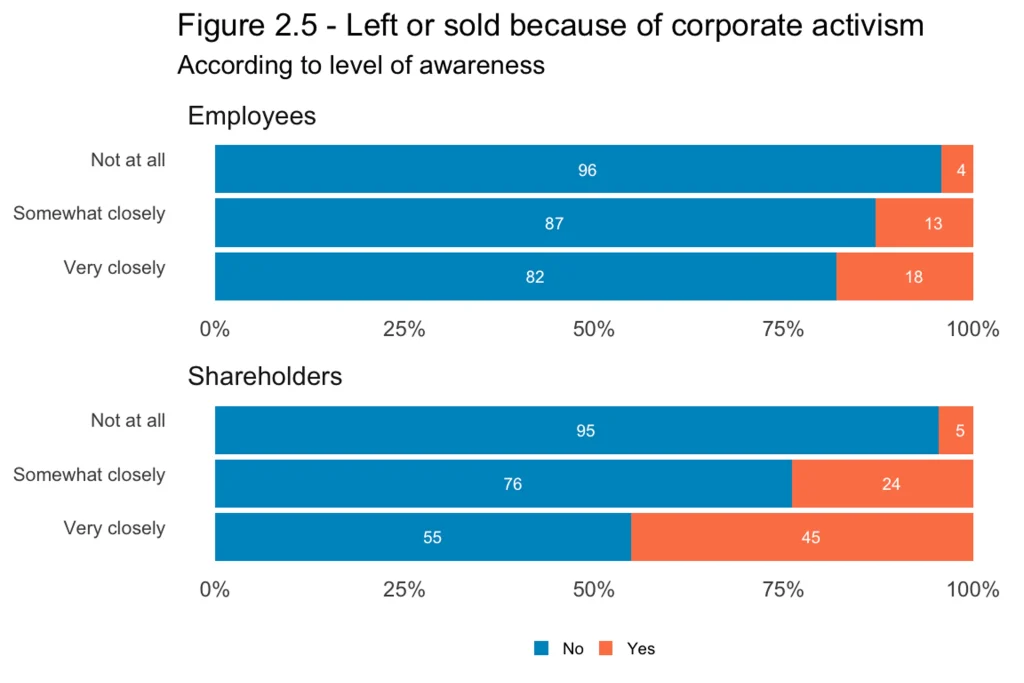

Those who follow their employer’s activism closely are much more likely to leave their company because of that activism (18% of employees who closely follow their employer’s activism say they have left a job for this reason). The same holds true for shareholders, with 45% of the most active saying they have, in fact, sold shares because of a company’s activism.

This would indicate that if companies are committed to activism they would be wise to avoid broadcasting that work; because when people find out, they leave or sell.

BOX: Response to corporate activism by Gen Z

Generational breakdown

There is a clear generational trend. Those in younger generations say they are significantly more inclined to make decisions about their employment and their investments based on company advocacy and activism than older generations. When put to the test, Millennials and Gen Zs report having followed through and left jobs or sold shares at higher rates because of corporate activism.

Of the 19% of Gen Zs who said they would leave a role because activism, 11% actually have. For Millennials, 11% say they would leave and 10% followed through. This may reflect how long Gen Z has been in the workforce.

Just over a third of Gen Zs say they would apply for a job because of corporate activism; however, the number who actually have is likely much lower. While corporate activism may help attract the newest batch of interns and entry level staff, it begs the question: is that gain worth the risk that more qualified, trained, and mature staff members may choose to leave as a result?

The figure showing the actions Boomers and Gen Xs have taken compared to Millennials and Gen Zs reveals a point of difference in the way these groups approach activism. Despite having spent more time in the work force, over half as many people from the older generations report leaving a job because of activism, compared to their younger counterparts.

This may in part reflect the fact that corporate activism has increased in recent years, so when older generations were at an earlier stage of their careers with less to lose, these initiatives were less common.

Surprisingly, more people have taken action because of corporate activism than report they would. This even holds true for employees — who have more to lose than shareholders by leaving a job, as opposed to selling shares. When people follow the actions of a company closely, they are much more likely to sell their shares or leave that company.

Corporations are paying a price for their activism. Not only does corporate activism increase staff turnover, but the activism appears to only appeal to a subset of the population, namely Gen Z, Greens voters. As a result, corporations are likely losing their most experienced people as well as important diversity of thought within their organisations. Any organisation benefits from having people with different worldviews and perspectives. If activism means a business is recruiting from a narrow subset of people and alienating the rest, it is missing out from the gains diversity brings.

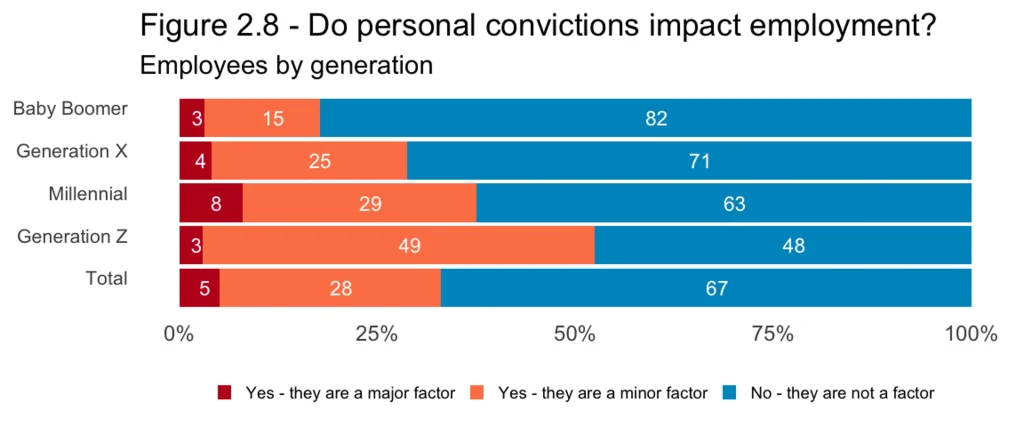

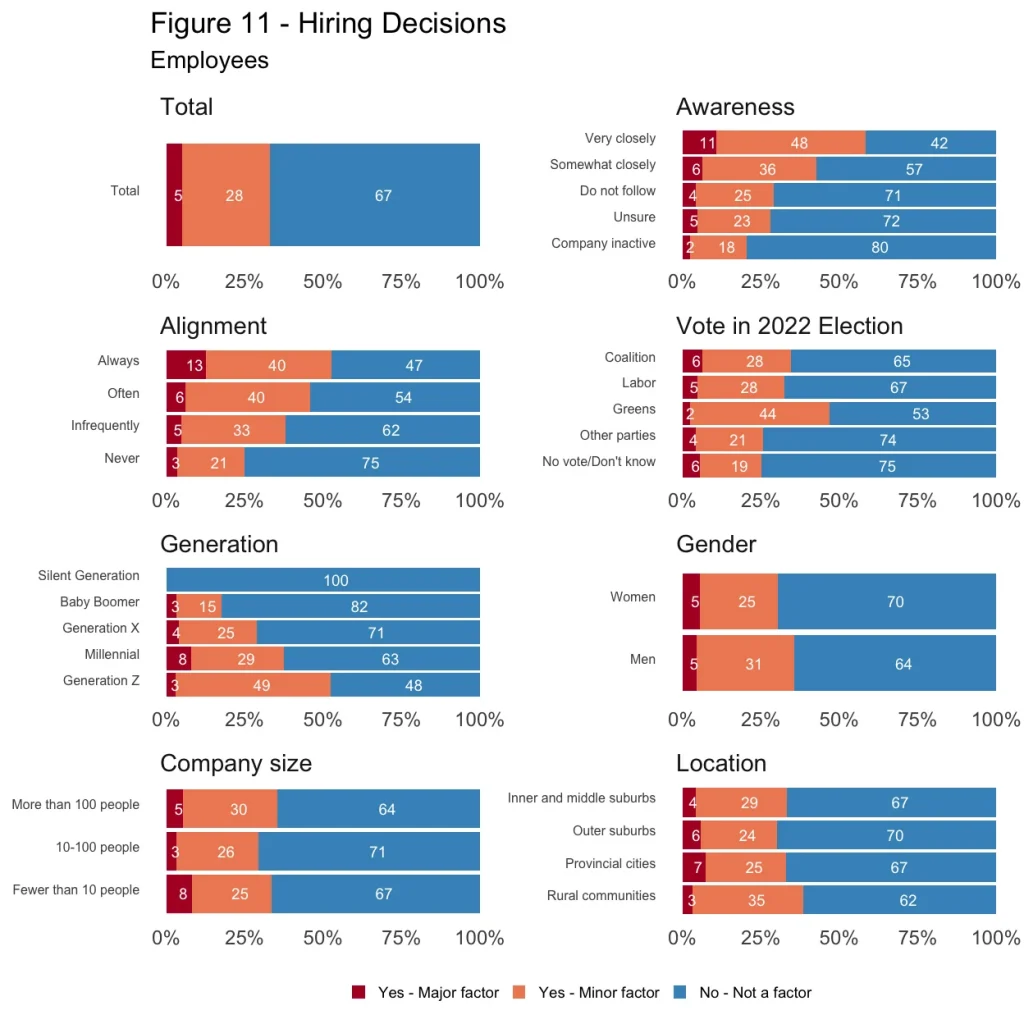

BOX: Hiring decisions

Ironically, people are more likely to believe they will be selected for a role based on their political beliefs than are to select an employer for that same reason. When asked whether they believed their employer considers political or personal views when evaluating potential hires or candidates for promotion, 33% of employees at private businesses responded in the affirmative.

There is also a clear generational trend, with over half of Gen Zs believing candidates’ personal beliefs are a factor in their companies’ hiring decisions. Millennials were the most likely to say it was a major factor.

What employees report doesn’t necessarily reflect the reality at corporations, merely the perceived reality. Gen Z, in particular, is the group least likely to speak for the values of their company as they are at the beginning of their careers and the ones being hired as opposed to making hiring decisions.

The fact that over half of Gen Zs believe employers make hiring decisions based on their personal beliefs likely impacts how they present themselves to employers, including through their social media presences.

That said, between 18% and 29% of Baby Boomers and Gen Xs believe personal and political views are a hiring factor at their companies. That number goes up significantly to 37% when looking at those from older generations who voted for the Greens in 2022. These are the people more likely to be established in their careers and making the hiring decisions, which would indicate young people may be correct about being judged based on their personal and political convictions.

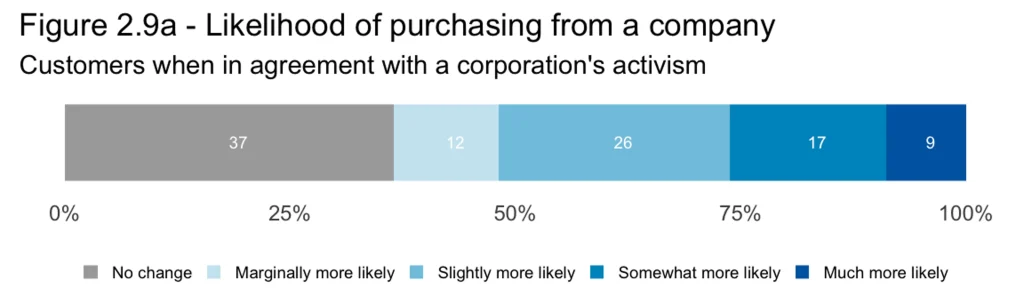

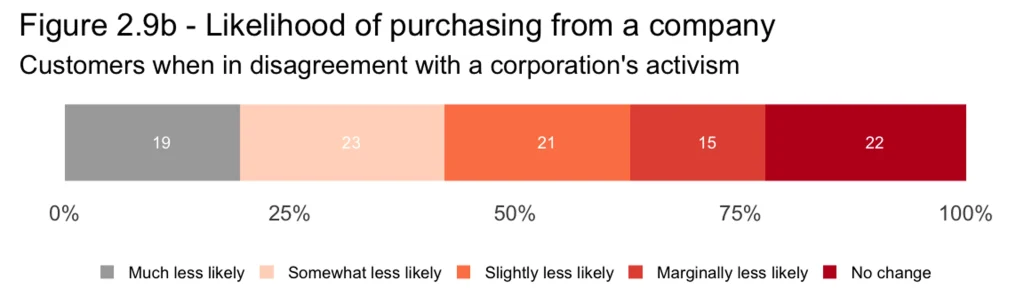

Corporate activism scares away more customers than it attracts.

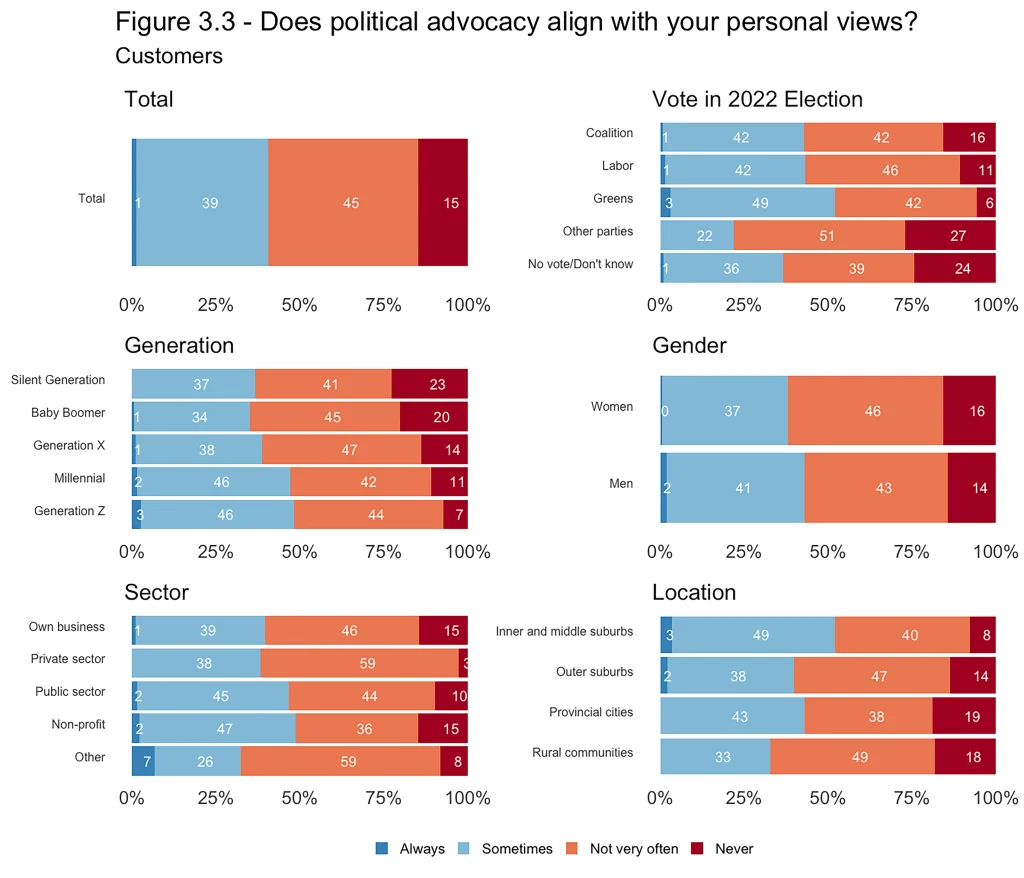

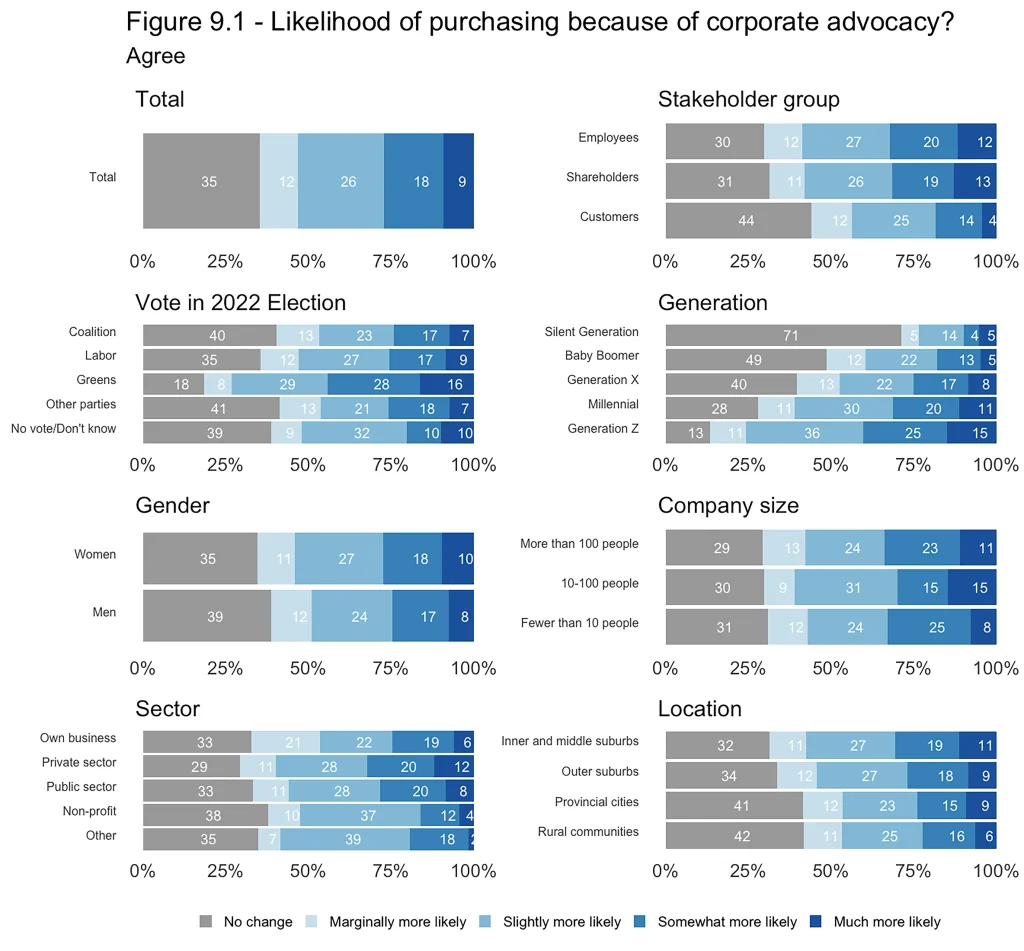

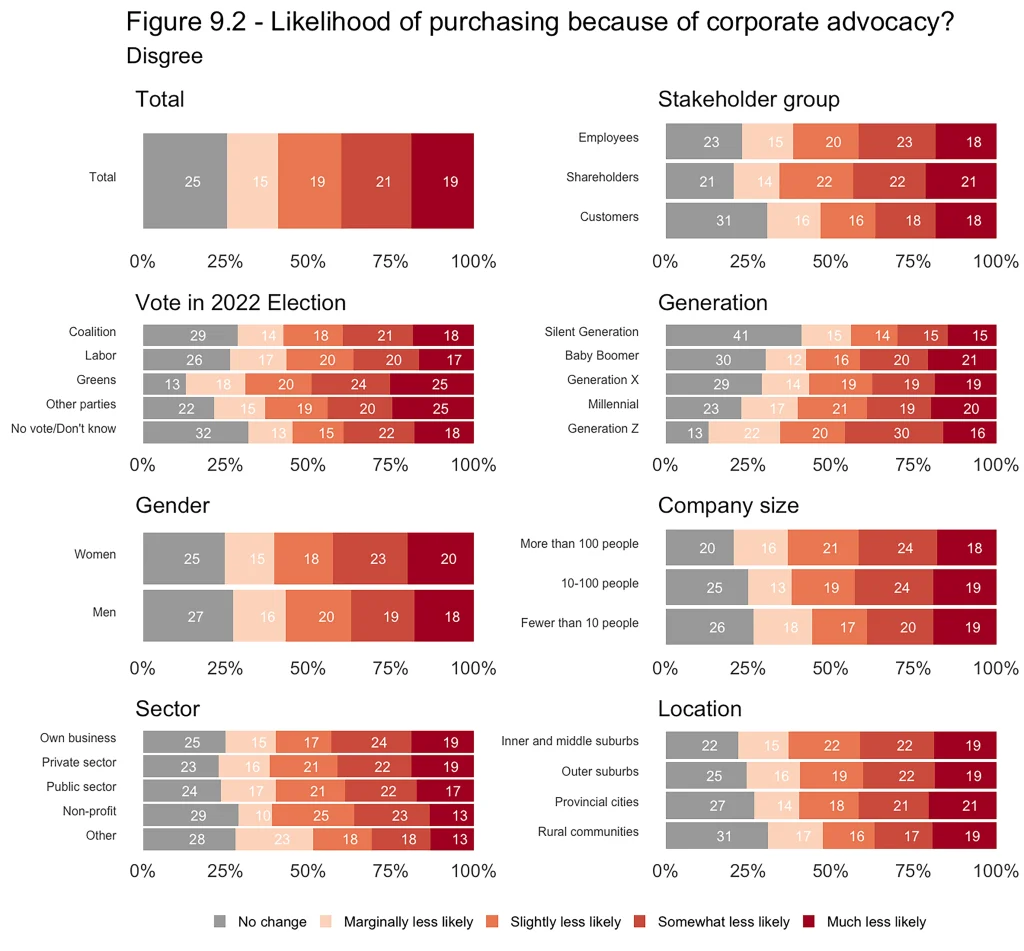

Even accounting for these costs, management may still value the investment in social and political causes for its potential to attract customers and increase sales. We asked all three samples how corporate activism impacts their purchasing decisions.

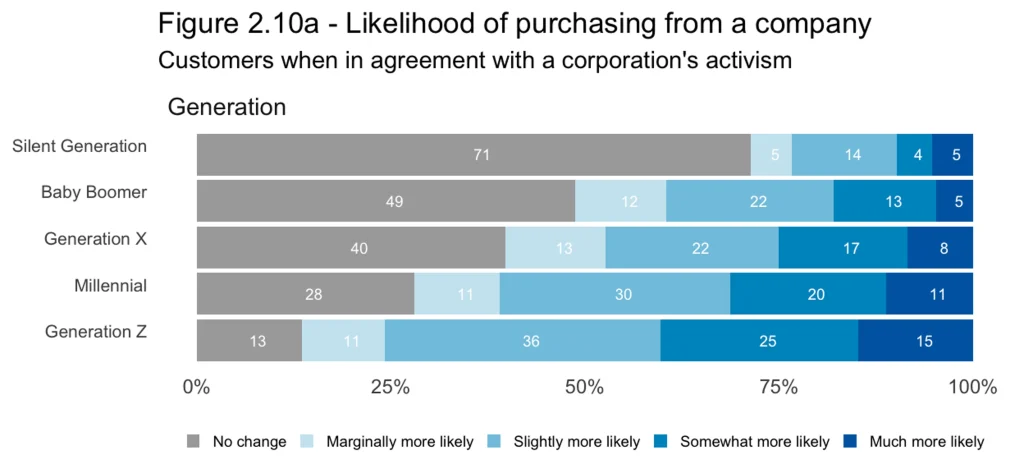

We found customers who agree with a company’s activism are much more likely to do nothing (37%) than those who disagree (26%).

Similarly, customers are more than twice as likely to stop doing business with a company they disagree with than they are to purchase from a company they agree with because of activist initiatives. This is the opposite response to what corporations would view as favourable.

BOX: Consumer behaviour across generations

Generational Breakdown

There is a very distinct generational trend, particularly when it comes to attracting customers. Many companies likely choose to communicate their activities through social media and influencers for just this reason.

However, while there is a less dramatic difference between the generations, younger generations are somewhat more likely to stop purchasing from a company because of their activism. Further, the likelihood of causing customers to boycott a business because of their activism is much higher than attracting customers, regardless of generation. In fact, Baby Boomers were the group most likely to say they are much less likely to purchase from a company they disagree with.

This suggests that when they are advocating for controversial issues, businesses might lose investors, employees and customers rather than attract them. The vast majority of metrics indicate the hours and dollars spent on activist initiatives —particularly controversial ones — are hurting companies on these key metrics as opposed to helping them.

The people who view corporate activism favourably are not overly sensitive to it. They don’t make decisions, from small purchases to changing jobs, based on the activist work at companies. Instead, they largely ignore it.

The only people who seem to view these initiatives in a positive light are mostly the youngest and most inexperienced within the organisation. They are more likely to be those with the least disposable income to spend or invest. Further, those young people’s views — at least those they present publicly — are likely influenced by a desire to impress the very employers who claim they engage in these activities to impress future hires.

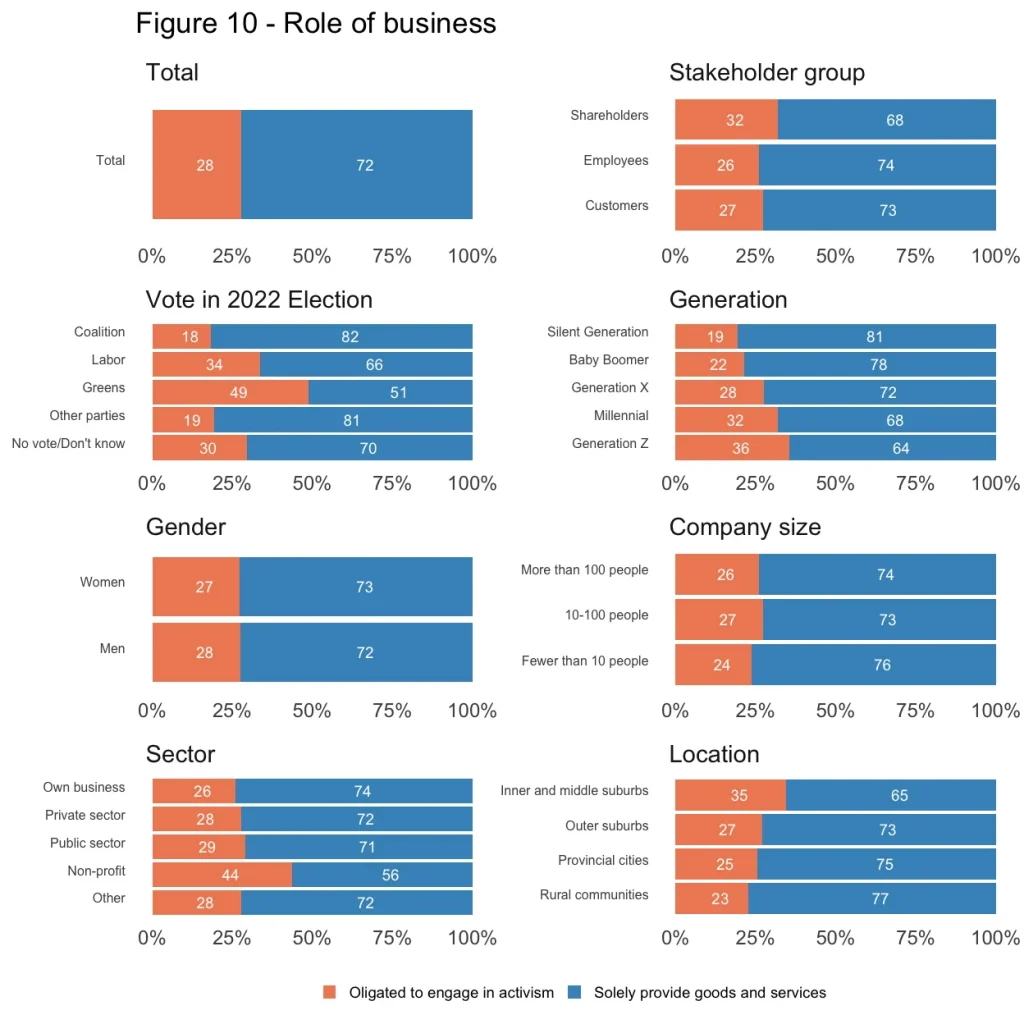

The role of business

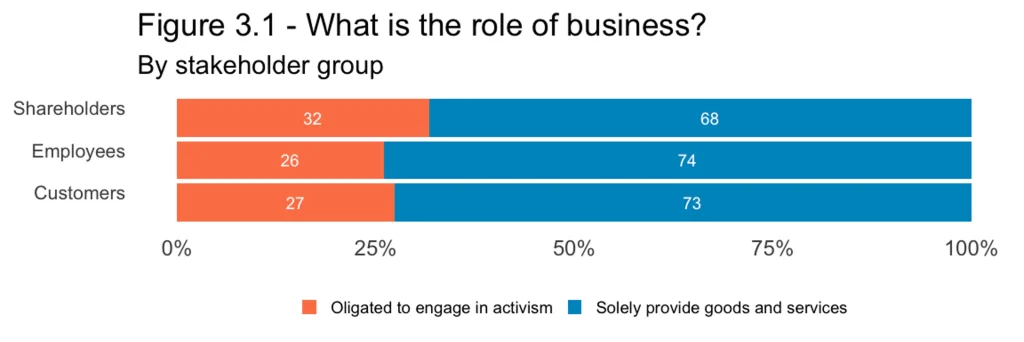

Before digging too deeply into why businesses undertake activism despite its potential to alienate employees, shareholders, and customers, it is worth asking the simple question: What does the community view as the primary role of business? In short, the question is should business primarily focus on providing good service to customers and high returns to shareholders and stay out of public debate? Or should businesses be leaders on contentious issues, even if this loses them customers and / or lowers shareholder returns?

While the overall response is strongly in favour of business sticking to business, a sizeable minority of people believe business has a role to play — even at the risk of alienating customers and financial losses.

Of course, it is possible this will be news to business leaders who are being pushed towards taking a view on topics the majority feel they need not express a public opinion on. Indeed, one might observe that the better explanation is that those pushing corporate activism are a noisy minority.

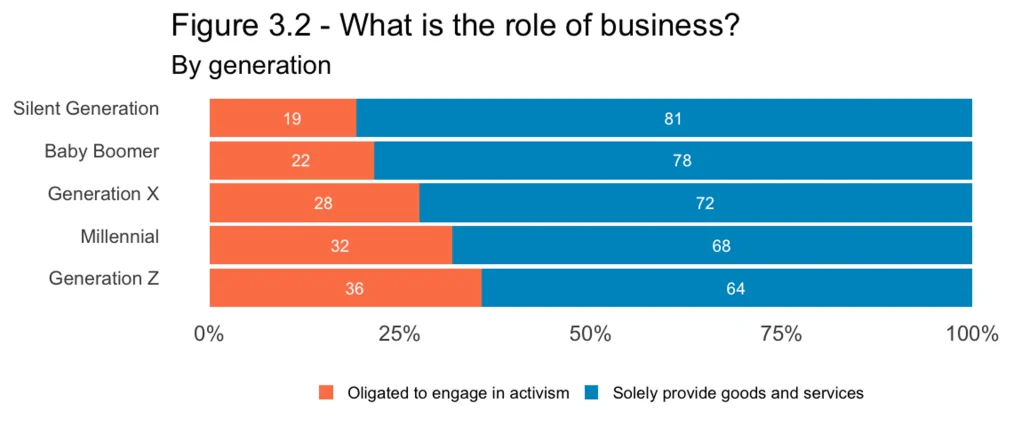

This is reinforced when we break down the results by generation. There is a trend of placing increasing weight on the need for business to intervene in contentious public debates. However, it is worth noting this remains a minority position, even among the youngest respondents.

When you combine the figures on the low support for business taking an active role in debate, with the earlier data on the general lack of awareness and support for corporate activism as a whole, a picture begins to emerge of a movement that is a mile wide but an inch deep.

What is less clear is whether business leaders are being driven into intervening in debate for fear of upsetting people and are not conscious of the lack of support for the positions being taken.

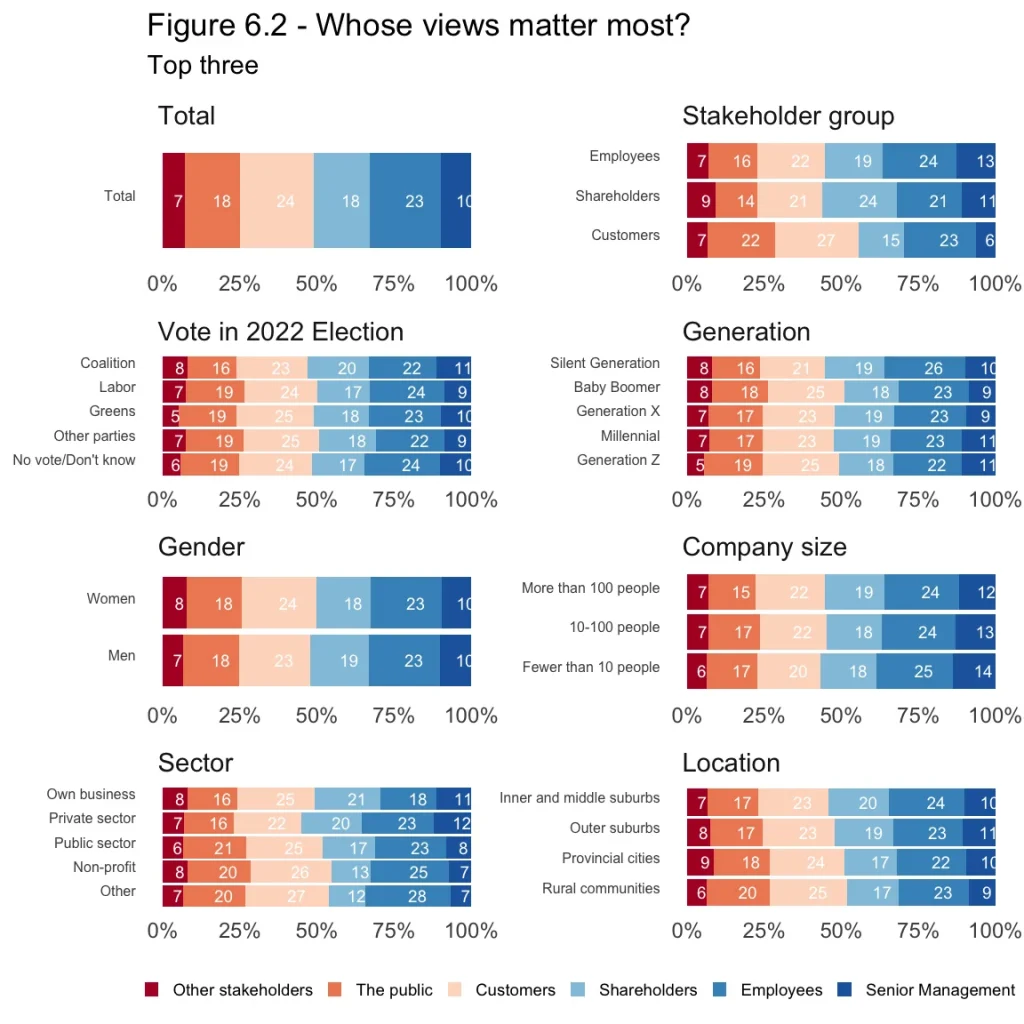

When it comes to corporate activism: whose views really matter?

One of the clearest ways to identify the evolving understanding of the role of business is to ask the question of whose views matter most when a business decides to engage in activism. After all, businesses — especially larger businesses — are hardly a monolith when it comes to opinions on contentious topics that divide society.

Historically, the simplistic answer was that the views of shareholders should be determinative of both the decision to engage, and what position to take. The slightly longer, but still simplistic answer, is that the directors are elected to act in the best interests of shareholders and therefore should act to discourage management from taking actions that would harm those interests.

Of course, it is worth noting that taking a controversial position, even if it is a position consistent with the views of a majority of shareholders, may be against shareholders’ interests if it causes the business to lose customers.

However, as noted above, there are other stakeholders who increasingly assert the need for their views to be taken into account.

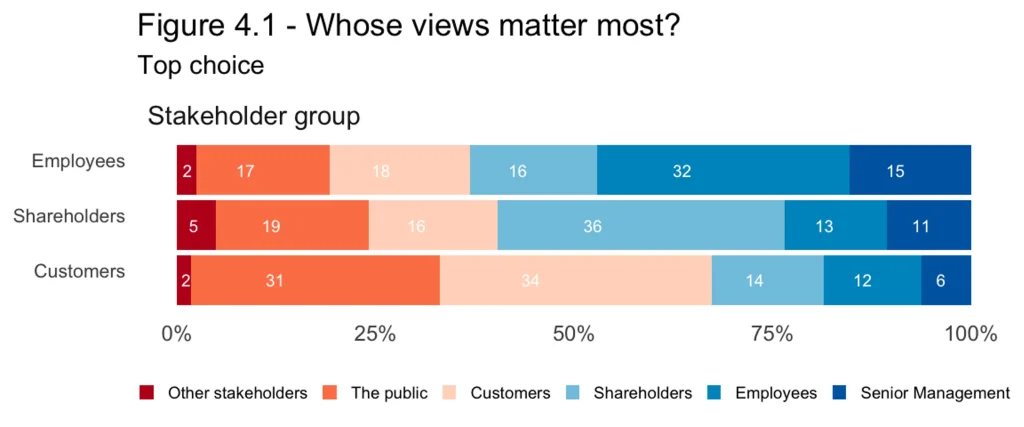

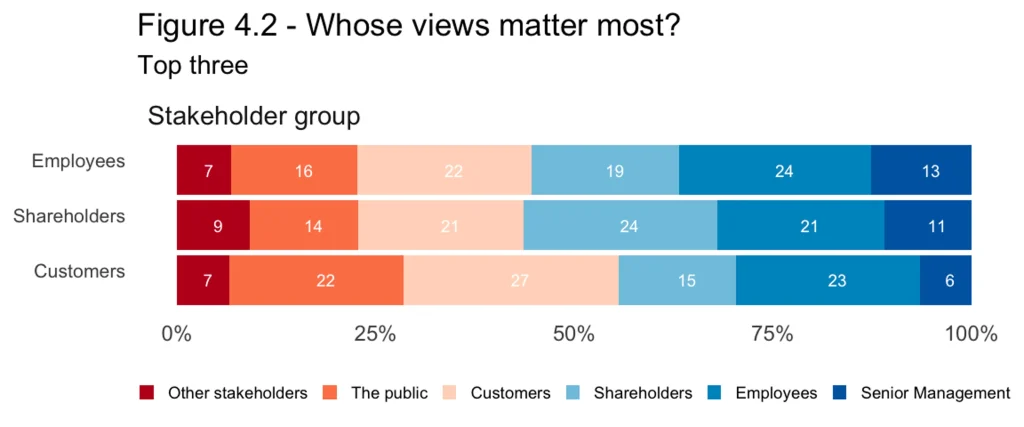

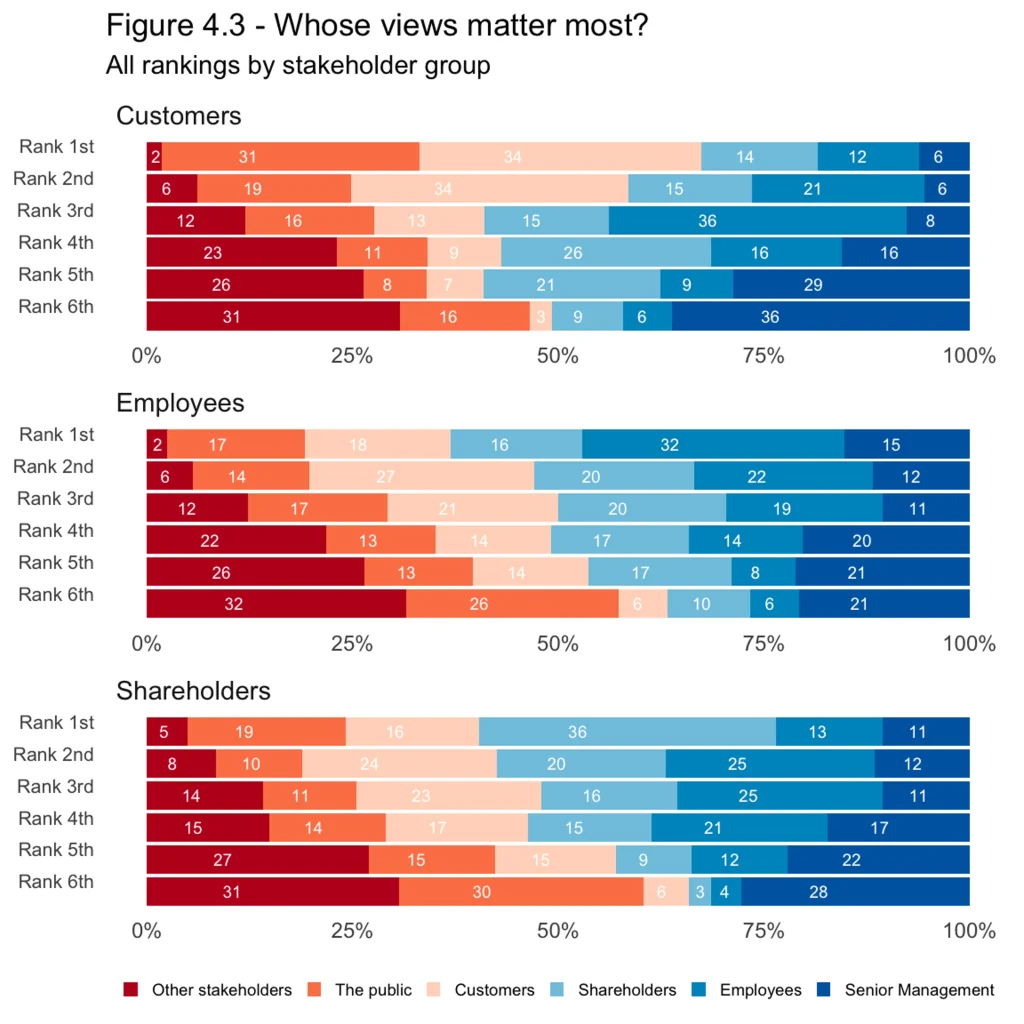

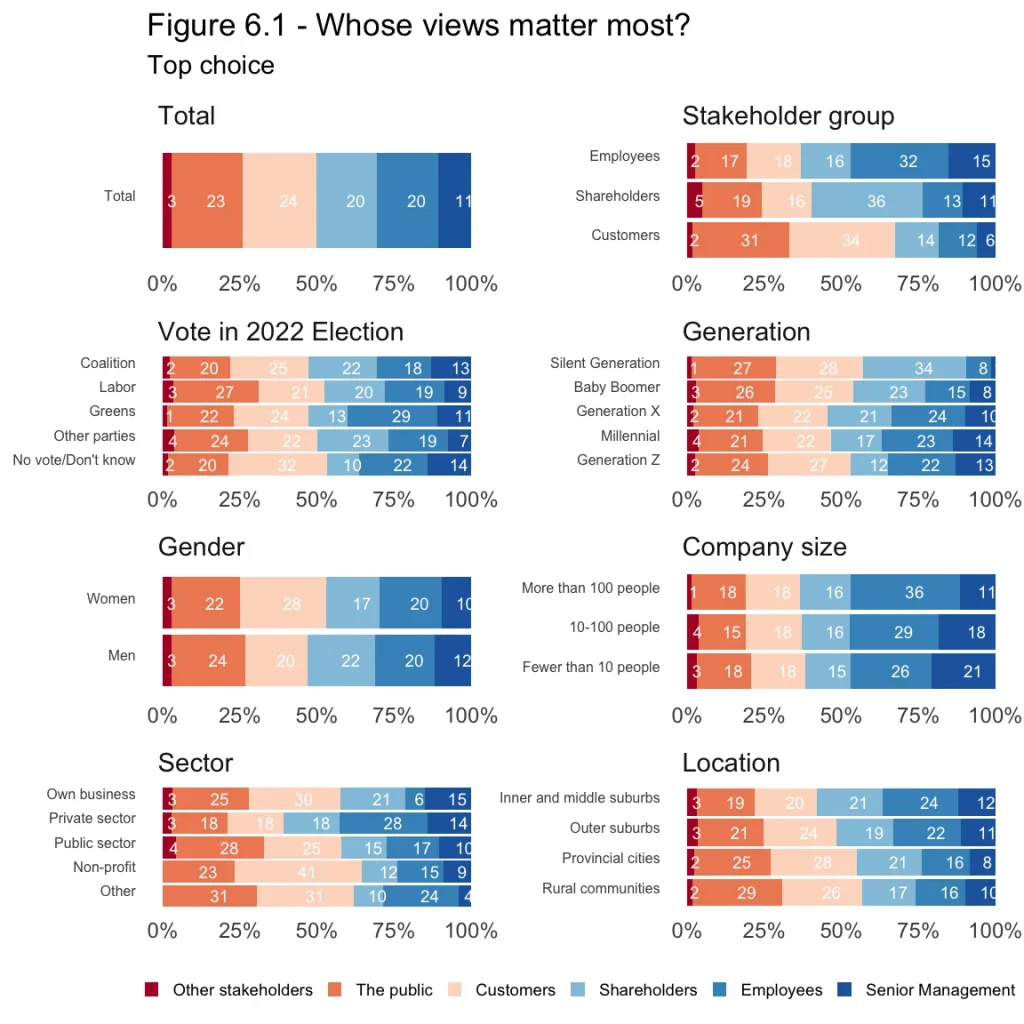

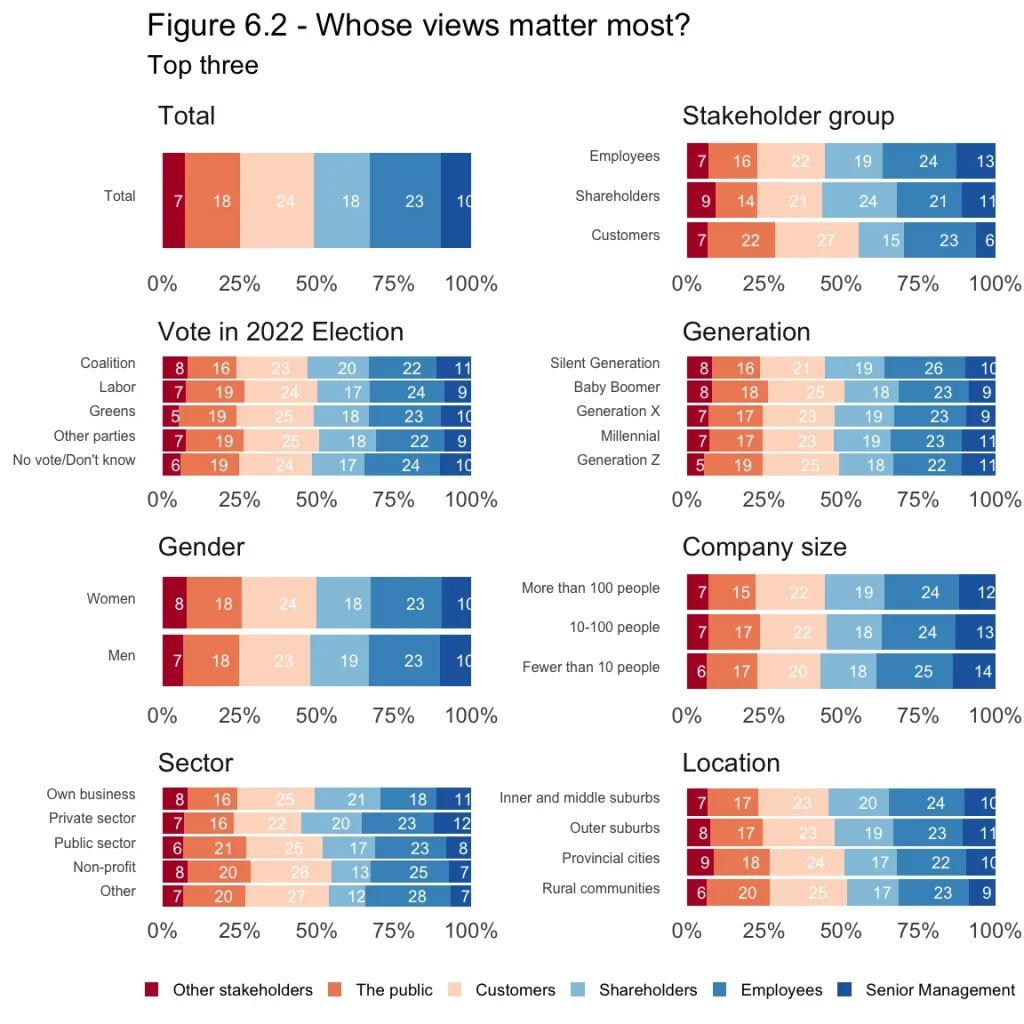

The survey data indicates the traditional view of the primacy of shareholder views is in decline. When looking at all groups, 25% ranked customers as the number one driver of activism followed by 24% selecting the general public.

Customers are far more likely to take the position that their views and those of the broader public matter more than shareholders, while employees rank the views of shareholders 4th behind themselves, customers, and the broader public.

Indeed, if we take a broader assessment and consider whose views are in the top 3 in each sample, the picture is arguably worse. Customers now place the views of shareholders a distant 4th, with just 44% of respondents ranking them in the top 3 on whose views matter.

56% of employees do have shareholders in the top 3, but this is more than 10% behind customers’ views on advocacy.

It is only among shareholders themselves that a strong majority (72%) rank shareholders’ views in the top 3. Indeed, if we exclude the survey responses of shareholders themselves, shareholders’ views rank 4th overall.

Given the historical importance of the views of shareholders, this should be a distinctly troubling result. Only the personal views of senior management and other stakeholders including suppliers, business associations and unions are considered less important.

However, despite as many as 3 in 4 respondents placing importance on listening to the views of employees, as we can see above a significant majority of employees (almost 60%) report the actions undertaken by companies in this area never or only infrequently align with their views.

This again suggests that the driving force behind corporate activism is not broad based.

Why then do businesses advocate for causes?

With corporate activism repelling a significant number of customers and alienating many experienced staff members, why then do companies invest so much in these initiatives? Why do almost all companies in our sample, as indicated by Figures 1.1 and 1.2, engage in social and political issues even when a majority of people think they should stick to providing goods and services to customers and high returns to shareholders?

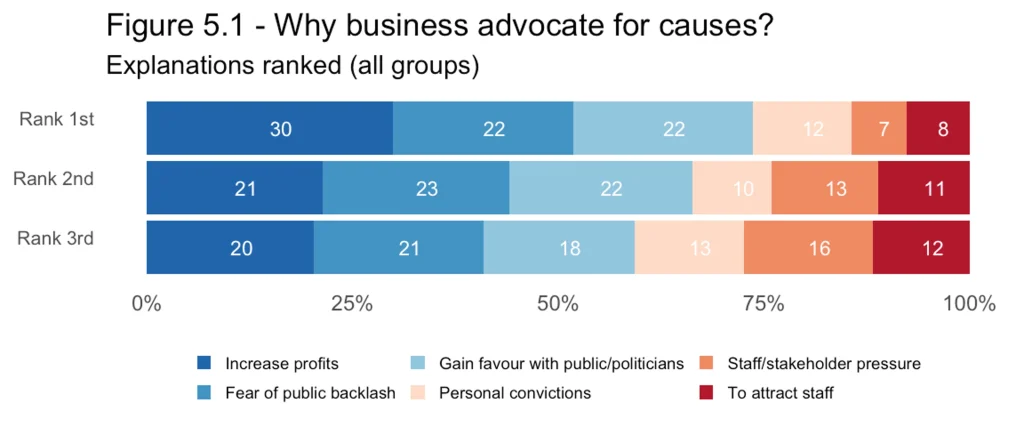

We asked all groups why, in their experience, they believe businesses undertake advocacy for social and political causes, especially on contentious issues? They were given the option to rank their top three reasons. The options included:

- personal convictions of senior leadership;

- internal pressure from staff and other stakeholders to support a particular position;

- a desire to attract staff, especially younger, more politically aware workers;

- a belief that this advocacy will lead to greater market share or higher profits;

- an attempt to gain favour with politicians and the media; and/or

- fear of a public backlash from not being on the ‘right’ side.

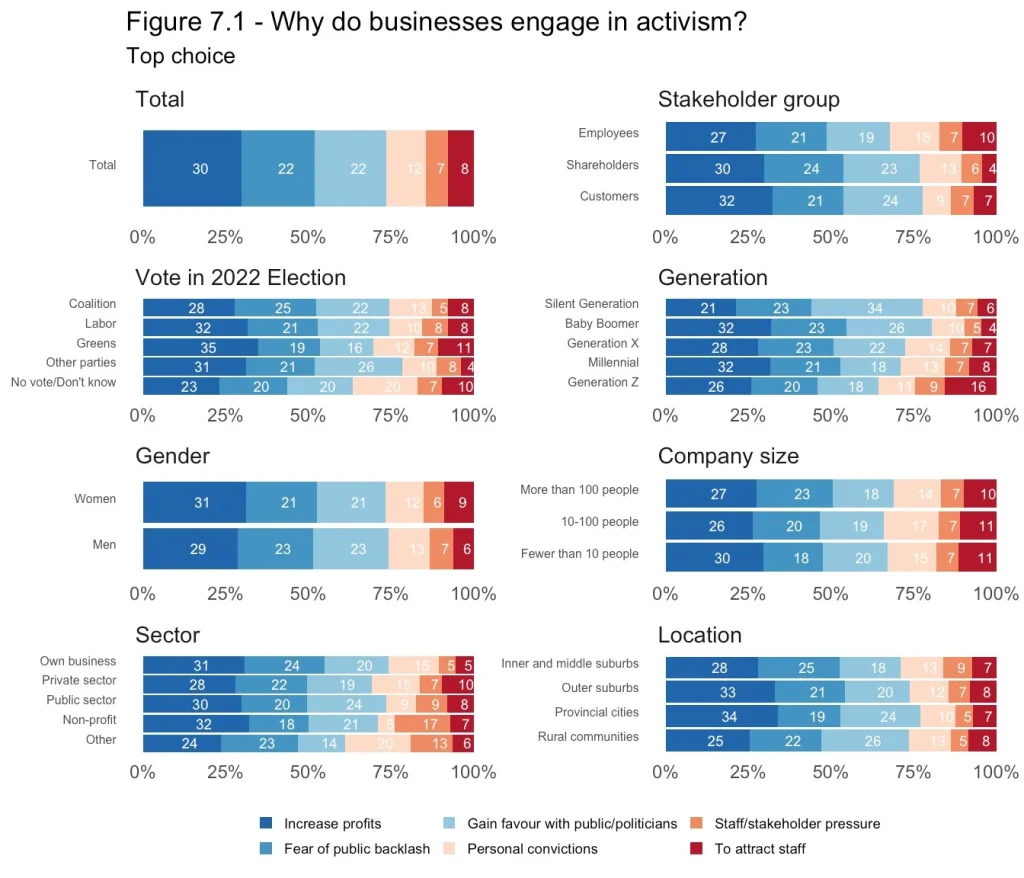

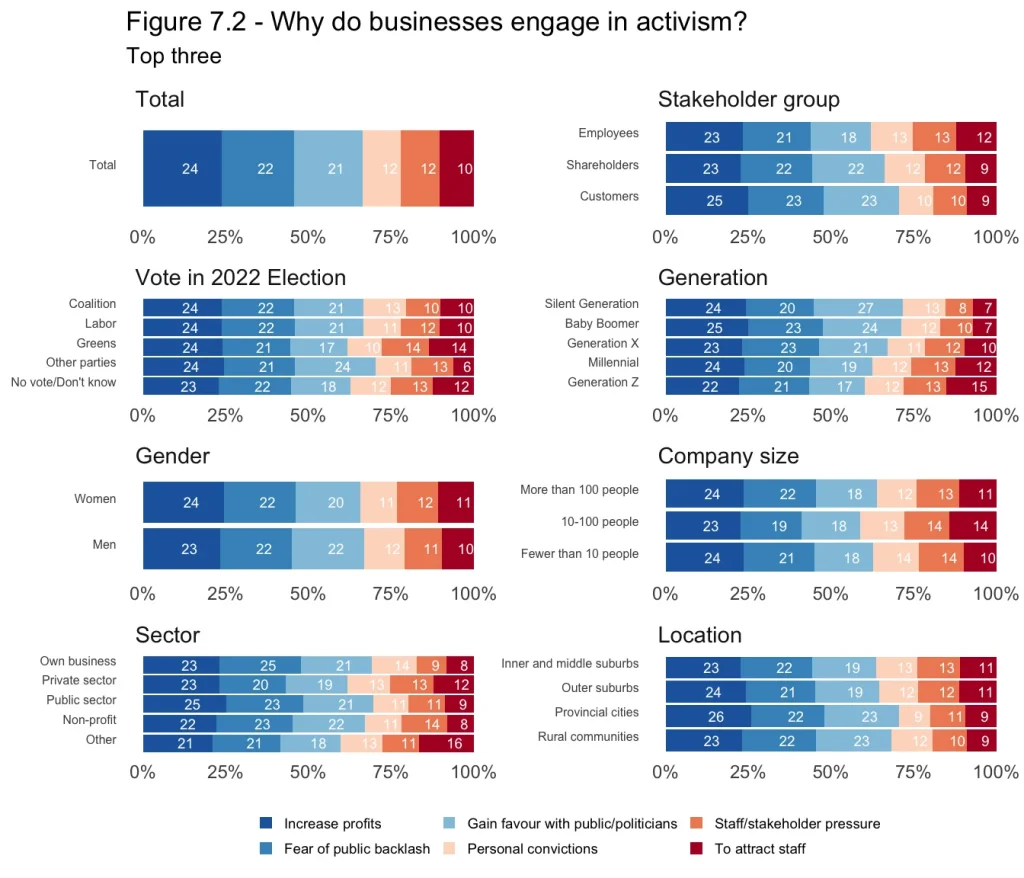

Almost a quarter of respondents chose ‘increasing profits’ as one of their top three explanations for corporate activism. This was followed closely by ‘fear of public backlash’, and ‘gaining favour with the public and politicians’. Last came ‘personal convictions’, ‘staff and stakeholder pressure’ and a ‘desire to attract staff’.

When looking at the precise rankings, all three groups disproportionately chose ‘increasing profits’ as the most likely reason corporations chose to engage in activism. ‘Stakeholder pressure’ was the least likely to be ranked as the number one reason. This holds true with the general finding of this paper. Only a minority of internal stakeholders support these initiatives and most believe the views of customers and the general public rank more highly than shareholders, employees, and senior management.

‘Staff and stakeholder pressure’ was unlikely to be listed as the first choice for any group. Shareholders in particular were unlikely to list ‘stakeholder pressure’ or ‘attracting staff’ as a reason.

Few believe corporate activism comes from a place of genuine conviction by those driving it. However, employees were more inclined than any other group to list ‘personal convictions’ as the number one reason for corporate advocacy. That said, still only 15% of employees ranked it first.

BOX: Why across generations

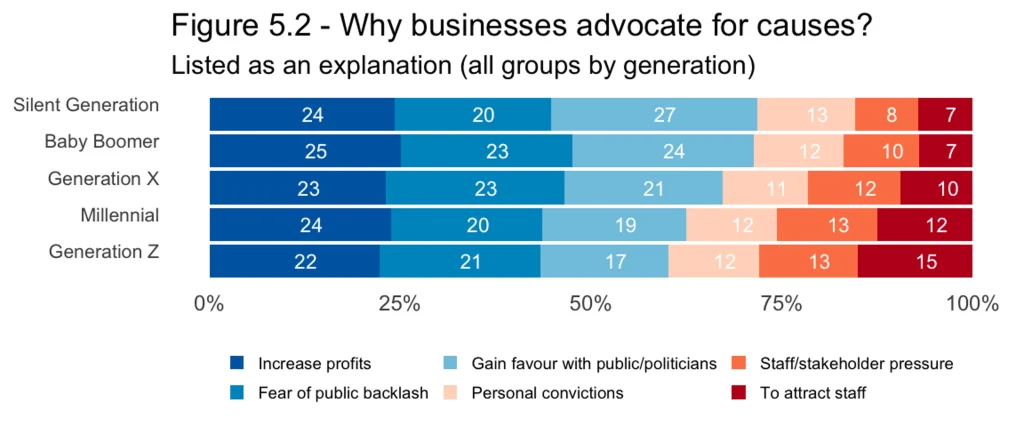

There is comparatively less difference across the generations in their views of the motivation for corporate advocacy than those described earlier. Most listed ‘increasing profits’ and ‘avoiding backlash’ as the top reasons for activism.

However, older generations were much more likely to list ‘gaining favour with politicians and the general public’ as an explanation.

Meanwhile, younger generations put ‘attracting staff’ and ‘staff and stakeholder pressure’ at higher rates than older generations. This is likely because they are themselves the staff members either attempting to drive activism or making job decisions based on activism. All other generational groups indicated corporate activism was unlikely to factor into their personal employment decisions.

Gen Zs were least likely to select ‘personal convictions’ as their number one reason. Most rank it third or not at all, making them the most cynical generation when it comes to the activities of corporations. This fact won’t be surprising to anyone who has seen any of the billions of TikTok videos tagged #corporationsbelike mocking large corporations for jumping on to political and social bandwagons like Pride Month or Black Lives Matter.

However, they are also the generation most likely to say corporations have an obligation to engage in the public debate on contentious issues.

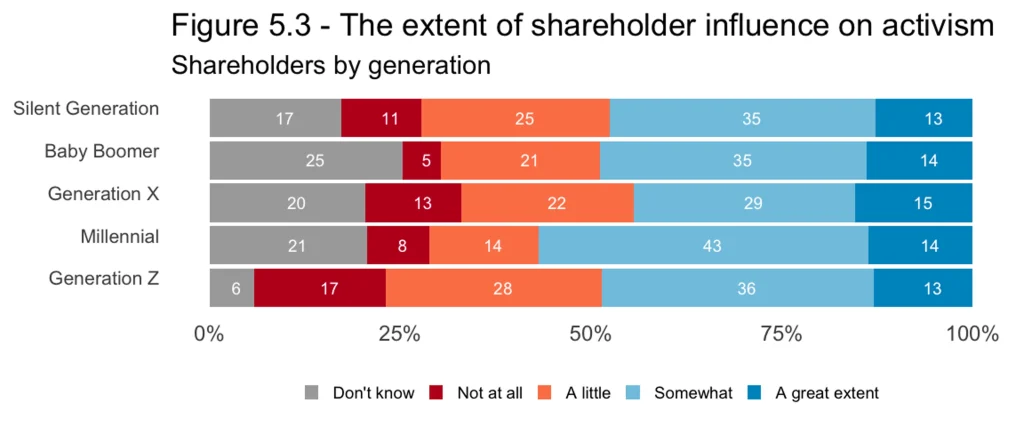

Finally, we specifically asked shareholders to what extent they thought institutional shareholders (like superannuation funds) influence the political and social advocacy of the companies they hold shares in. Gen Zs confidently responded with ‘not at all’ or ‘only a little’ at much higher rates than other generations. Meanwhile, Millennials struck a different chord as the group most likely to say institutional shareholders do influence political and social advocacy.

Pandering to the media and politicians, and fear of backlash from left-leaning journalists, seem like more salient reasons for why companies would get involved in activism. Some companies have faced significant criticism for failing to engage on certain issues, particularly those framed as being of global significance. Absent the information that these threats are not supported by the majority of their stakeholders, management may be inclined to give in.

Few seem to believe the oft-given excuse that young employees, and a desire to attract fresh young talent, drives activism. Instead, most agree the drivers of corporate activism could be tracked by following the money.

However, if respondents are correct that corporations engage in activism to increase profits, then the initiatives are misguided indeed; with customers and investors more likely to boycott than give their dollars to activist businesses.

Does corporate activism help or harm the cause?

There is a wealth of literature that looks at the issue of whether corporate social activism benefits or harms the bottom line of the company. Future CIS work will also examine this position. What is less well studied is the effect this support has on the cause itself.

Taking carefully crafted media statements at face value, activist managers care deeply about these causes and see their businesses as providing a true benefit to society. But self-interested reporting is hardly proof. Another way to examine the issue is to ask other stakeholders whether they think the investment helps or hurts these causes. Given the relative lack of engagement by most stakeholders, their perceptions of the effectiveness of corporate activism is much more likely to be dispassionate.

Of course, some cynics have suggested that support from big business ‘elites’ might actually have a negative effect in the current polarised political environment.

There is also a less cynical argument in support of this position. One of the likely motivations for businesses to engage in social causes is to burnish a less than stellar public reputation. If we accept that associating with a popular cause can improve the image of its supporters, it stands to reason that the reverse is also true and the negative reputation of businesses associated with a cause may ‘rub off’ on the cause itself.

A relatively extreme analogy would be the perceived negative effects of sporting codes historically partnering with tobacco companies, and then subsequently with alcohol and gambling businesses. Of course, in the eyes of the recipients of financial support, the negative social effect might be offset by the positive benefits that come from sponsorship dollars. It is possible that whatever gains can be made with the sponsorship dollars compensates completely for the negative reputational damage.

While some cynicism is no doubt warranted when it comes to business support for social causes, it may be possible to also take this too far. For example, even if you accept that the prominent support of major corporates who donated significant sums of money to the Indigenous Voice campaign self-evidently didn’t help win, it is another thing entirely to conclude that it was corporate support that caused the referendum to be lost.

It may be that the corporate support was slightly positive, or at worst benign, but that the effect was overwhelmed by the overall negative trajectory of the campaign.

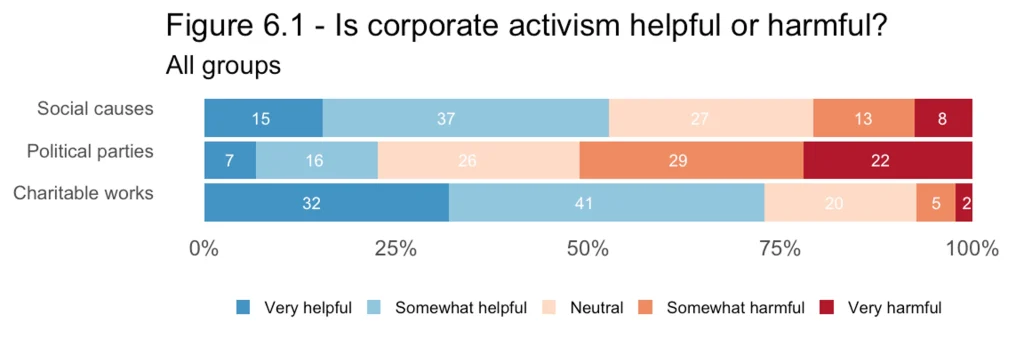

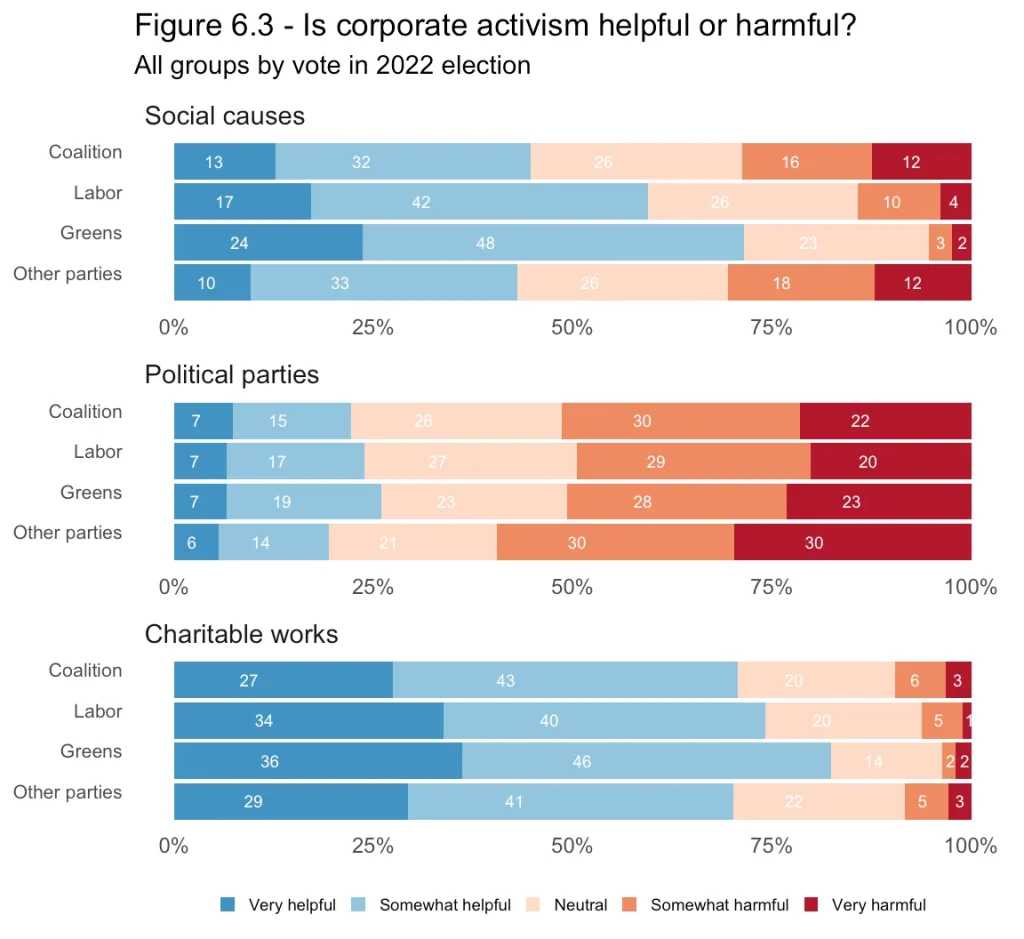

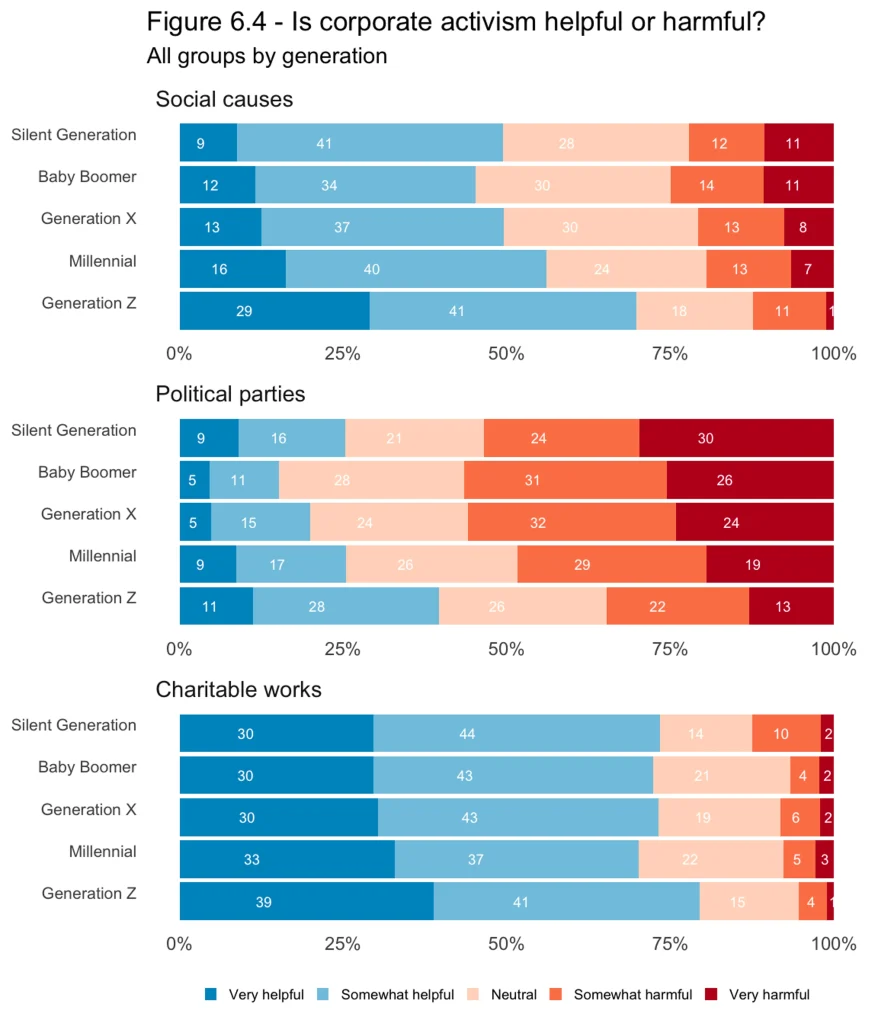

Interestingly, survey respondents had sharply divergent views about the benefits of corporate support for activism, political parties and charitable works.

Certainly, the overwhelming consensus is that corporate charity is helpful, with just 7% of respondents arguing it harmed these causes and 20% more ambivalent. This does not mean every corporate initiative in the charitable space is effective; but overall, the perception is positive.

On the other side, the consensus is that corporate political donations do more harm than good; with more than 50% responding it caused some level of harm and another 26% arguing it was ineffective.

The phrasing of the question was designed to reflect the views of the respondents on the fortunes of the political parties, although it cannot be ruled out that some who responded did so on the basis of a perception that political donations were harmful to society.

Others may have considered the bigger picture issues — arguing not that political donations cause parties to lose votes, but a perception that political donations may come with strings attached which outweigh the financial benefits.

When it comes to corporate activism on social causes, the responses are more mixed. A majority (52%) believes the effect is positive, while just 21% view the intervention as harmful. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is those who are most closely aligned with the goals of the activism that believe it to be the most helpful.

In some respects, this is a double-edged sword for those seeking to justify greater corporate involvement in activism. After all, it is the ‘never aligned’, and those ‘infrequently aligned’ who need to be convinced of the merits of the action in question. The belief that corporate activism is effective is strongest among those who need the least convincing.

BOX: Is there a generational trend?

Generational Breakdown

There is an interesting generational trend present in this data. Gen Zs are exceedingly unlikely to believe corporate activism is very harmful compared to other generations, and almost twice as likely to say it is very helpful even if they are jaded about the motivations behind these activist initiatives.

Older generations, on the other hand, are far more likely to believe corporate activism has little or no effect.

The interesting question is the extent to which this generational difference has more to do with a greater alignment of younger generations with the goals of activism vs a degree of world-weary cynicism that naturally comes with growing older. This point is likely countered by the Silent Generation result. However, it is worth noting the smaller sample size for the Silent Generation as they now make up a much smaller proportion of the overall population.

Analysis and conclusion

On the face of it, it seems there is a tacit acceptance among managers that, once they reach a certain size, companies need to acquire a social licence through engagement in corporate activism, political donations and / or charitable works.

Small businesses often engage directly with their local community too — for example, sponsoring a local sports team or donating prizes for a school raffle — but usually the motivation and benefit is clear. They support activities they have a personal interest in or connection with (their child’s school, a family friend’s charity, perhaps a sport they played as a child) or where they have a potential commercial interest (for example, a real estate agent might sponsor a school’s charity drive as a way to connect with homeowners in their area).

At scale, business initiatives seem far less likely to be direct and tangible. Modern corporate activism is enamoured with raising awareness: of inequality, racism, discrimination, climate change or poverty, to name just a few. Large businesses seek to align themselves prominently with popular, typically progressive, causes.

It should be noted these initiatives are often pro-forma endeavours: commissioning a rainbow logo, or drafting a Reconciliation Action Plan that, once written, may be filed away and never seen again. It is not always clear that these businesses are willing to do much internal soul-searching. The focus is almost always on the perceived faults of others, rather than a willingness to change their own practices or procedures, certainly at the top level.

In that sense, a lot of corporate advocacy is intentionally performative. It’s almost as if the first priority is to be seen, not to be effective.

This goal is at odds with the data presented in this report, which makes clear the majority of customers, shareholders and employees are unaware of the initiatives being undertaken by the companies they are associated with. This is true, even among Generation Z.

Moreover, of those who are aware of the actions of the companies they are engaged with, the majority of them have personal views that are not aligned with the positions taken by the company most of the time.

To top it off, a clear majority of people do not support activism of this sort by companies. Neither employees nor shareholder believe companies should be taking positions on contentious public debates.

The question that remains to be answered is: why do they continue to do so?

One theory, consistent with the results from this survey, is that a small group of engaged activists have a disproportionate influence on the behaviour of companies. It is those who are both most closely engaged with the activism of companies, and in alignment with the positions taken, who are most likely to change their behaviour as a result of corporate activism.

In this limited way, it may make business sense (superficially) for companies to engage in progressive activism. Sure, most of their employees and shareholders will disagree with the position taken, but perhaps they won’t do anything about it. Those who are strongly aligned and engaged might buy shares or take a job at the company. In a sense, this rationale is based on the idea that the progressively aligned potential shareholders and employees are the marginal actors.

One problem with this reasoning is that the groups are not of similar size. The group that might be more likely to act is far smaller than the group less likely to act. It is not clear that, when adjusted for relative size, more people would buy shares or take a job as a result of progressive activism, than would leave or sell.

In fact, some of the data in this report suggests, overall, slightly more customers who disagree with the positions taken by a company on these contentious issues will act than customers who agree.

It is also true that the groups most likely to view these initiatives in a positive light include the youngest and most inexperienced prospective employees. They are also likely to be those with the least disposable income to spend or invest in shares.

Balanced against this is the possibility that those with favourable views of this activism are not just found in a minority of progressive employees and shareholders. It is also highly likely they are directly involved in making decisions on what causes to support.

It seems very likely those attracted to a career in managing ESG initiatives will be disproportionately made up of people very engaged in issues of corporate activism. The results of the polling conducted in this report suggest those people are also much more likely to hold progressive views as indicated by their vote in 2022 election and their vote intention.

Therefore, it seems reasonable to conclude the push towards corporate activism, and its progressive alignment, is being driven by a small group of current and potential employees and shareholders outside management, and a small group of highly influential advocates within organisations.

These groups may be misrepresenting, or obscuring, the level of support for these initiatives among the bulk of employees and shareholders (not to mention customers), relying on the fact that most of these later groups are paying little attention to what is being done.

There is no support in the results of this survey for the view that corporate activism has a broad base of support with stakeholders, nor significant appeal with the general public. Quite the opposite in fact. Moreover, it is not just that stakeholders were not aligned or aware: only 28% felt companies were obliged to engage in activism at all, while 72% of respondents thought the role of business was solely to provide goods and services.

Many were also quite cynical about why businesses were engaging in advocacy. More than half the respondents thought the primary reason was to increase profits or of fear of backlash. Many others thought it was about currying favour with politicians.

Other potential justifications for engaging in advocacy for progressive causes also don’t hold water. Less than 10% of potential employees believe personal views are a major factor in hiring decisions. Companies do not have to engage in activism to be seen as a desirable place to work, nor do potential employees believe support for this activism significantly improves their chances of getting a job.

Although this result was concerning for other reasons, it is clear respondents to this survey felt the views of customers and the general public should be the most important consideration for companies positioning in public debates. This means that, when it comes to contentious issues that are dividing society, companies might be well advised to not take a position.

There is little support in the results of this report for the view that companies would be better off continuing to engage in social activism but from a more explicitly conservative position. Doing nothing is almost certainly the best approach from a business perspective.

Providing good service to your customers, treating your employees with respect and acting responsibly with your shareholders money is a far better — although less immediate or conspicuous — way to gain the broader public’s support.

Senior management should also be concerned they are putting their companies at risk of reputational harm if they associate with movements that are, or become, viewed negatively by the general public. Movements that may seem innocuous or non-threatening — like anti-racism — often turn out to be led by individuals with extreme views that many people find deeply obnoxious when they are made public. Corporate activism may have some upside, but the downsides seem more likely and more significant.

The findings of this report should give strength to managers who feel bullied into taking a public position on contentious social issues, and make those who have been convinced to do so take pause. It seems possible that ESG stands not for environmental, social and governance but for Emperor Sans Garments.

Appendix A: Complete survey results

1. Company involvement in activism

Questions

QA1: Shareholders and employees

How closely have you followed the actions of [your employer/the companies you hold shares in], in the following areas?

a) Advocacy for social causes

b) Political donations

c) Charitable works and donations

QB1: Customers

There are several industries in Australia dominated by a few large companies, including banking, supermarkets, airlines and department and hardware stores. Most of us are a customer of one or more of these huge companies.

Several of these companies have increased their political and social engagement in recent years. Have you observed the following?

a) Companies advocating for or donating to social causes

b) Companies advocating for or donating to political parties

c) Companies advocating for or donating to charitable causes

Analysis

2. Awareness

Analysis

3. Alignment

Questions

QA2: Employees and shareholders

When considering the following initiatives, how often do the actions of [your employer/ the company you hold shares in] reflect your personal views and beliefs?

a) Advocacy for social causes

b) Political donations

c) Charitable works and donations

QB2: Customers

How often does the political advocacy of major companies align with your personal views?

Analysis

4. Past behaviour change

Question

QA3: Shareholders and employees

When thinking about actions that have been undertaken in the past by companies you have [worked at/held shares in], have you ever [left your employer/ sold your shares] because of their…

a) Advocacy for social causes

b) Political donations

c) Charitable works and donations

Analysis

5. Reported behaviour change

Question

QA4: Shareholders and Employees

Would you [Leave your job/Sell your shares] OR [Apply for a job/Purchase shares] because of a company’s …

a) Advocacy for social causes

b) Political donations

c) Charitable works and donations

1. Yes – [Leave your job/Sell your shares]

2, Yes – [Apply for a job/Purchase shares]

3. Neither of these

4. Not sure

Analysis

6. Whose views matter

Question

QA5 and QB5: All groups

When it comes to making decisions on whether to undertake advocacy for social causes, make political donations or giving to charity, whose views are most important for a company to consider? Rank the following from most important to least important, where the most important option is ranked 1, and so on.

1. Shareholders

2. Employees

3. Board and Senior Management

4. Customers

5. The general public

6. Other stakeholders (e.g., suppliers, business associations, unions, etc.)

7. Not sure

Analysis

7. Why businesses advocate

Questions

QA6: Employees and shareholders

In your experience, why do you believe businesses undertake advocacy for social causes, especially on contentious issues?

Please select the three most important reasons companies advocate for social causes; where rank 1 is the most important, and so on.

1. Personal convictions of senior leadership

2. Internal pressure from staff and other stakeholders to support a particular position

3. A desire to attract staff, especially younger, more politically aware workers

4. A belief that this advocacy will lead to greater market share or higher profits

5. An attempt to gain favour with politicians and the media

6. Fear of a public backlash from not being on the ‘right’ side

7. Not sure

QB6: Customers

As a customer, why do you believe businesses undertake advocacy for social causes, especially on contentious issues? Please select the three most important reasons companies advocate for social causes; where rank 1 is the most important, and so on.

Analysis

8. Help or harm?

Question

QA7 and QB7: All groups

How helpful or harmful do you think support from big business is for the following?

a) Advocacy for social causes

b) Political parties (through donations)

c) Charitable works and donations

Analysis

9. Purchasing Decisions

Questions

Employers and Shareholders

QA8: Now thinking as a consumer, how much more likely are you to buy a company’s goods and services if that company advocates for a cause you agree with?

QA9: Now thinking as a consumer, how much less likely are you to buy a company’s goods and services if that company advocates for a cause you disagree with?

Customers

QB3: How much more likely are you to buy a company’s goods and services if that company advocates for a cause you agree with?

QB4: How much less likely are you to buy a company’s goods and services if that company advocates for a cause you disagree with?

Analysis

10. Role of Business

Question

QB8: All groups

Which of the following statements most closely aligns with your views?

1. Businesses should primarily focus on providing good service to customers and high returns to shareholders and stay out of public debate.

2. Businesses owe obligations to the broader community and should be leaders on contentious issues, even if this loses them customers and / or lowers shareholder returns.

Analysis

By stakeholder group and total

11. Hiring decisions

Question

QA10: Employees

Do you believe your employer considers political or personal views when evaluating a potential hire or a candidate for promotion? ASK employees only

1. Yes – they are a major factor

2. Yes – they are a minor factor

3. No – they are not a factor

Analysis

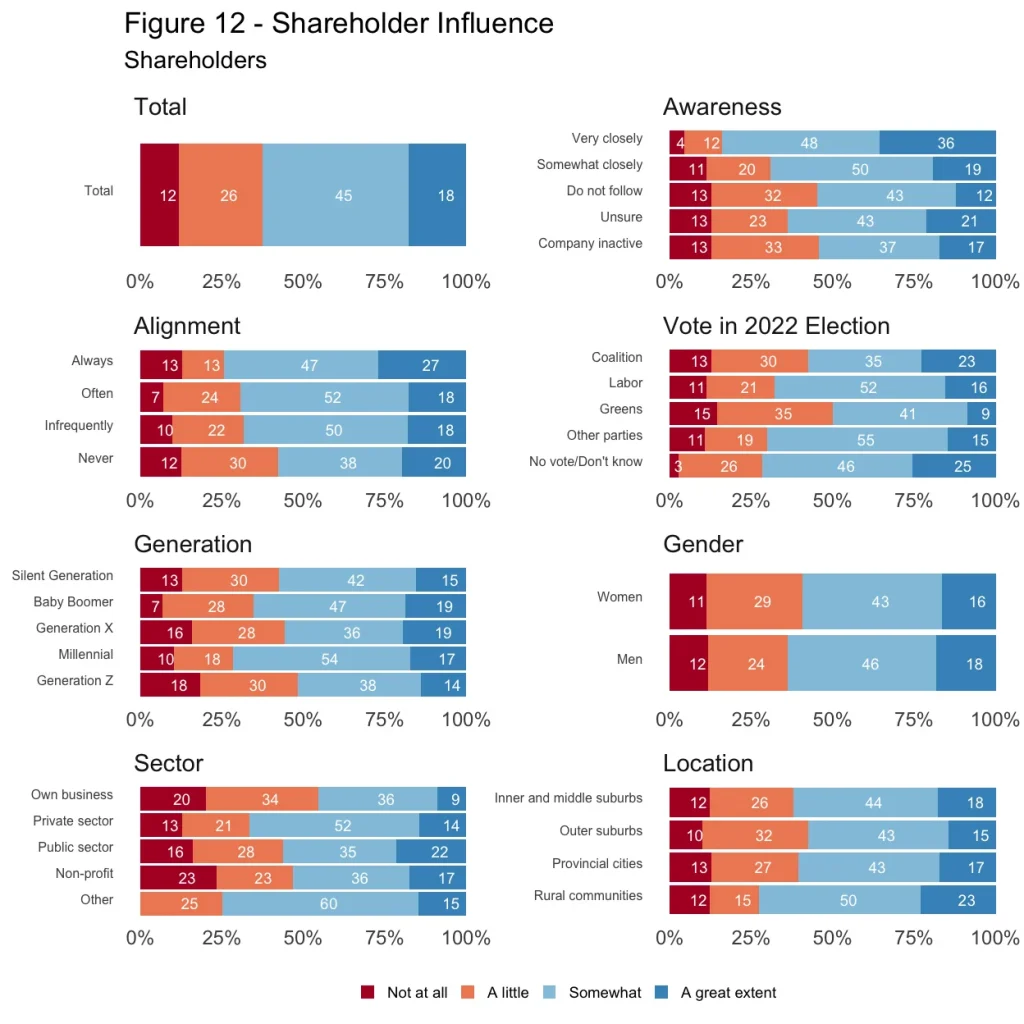

12. Shareholder influence

Question

QA12: Shareholders

To what extent do you believe institutional shareholders (like superannuation funds) influence the political and social advocacy of the companies that you hold shares in?

1. A great extent

2 Somewhat

3 A little

4 Not at all

5 Don’t know

Analysis

Appendix B: Survey Methodology

The fieldwork for this survey was conducted between Wednesday 10 and Monday 22 April. The sample included 2,521 Australian citizens aged 18 and older, who were enrolled to vote. They were recruited via an online panel to fill quotas based on age, gender, location (regions, based on electoral division), education, and vote at the 2022 federal election. The sample was then segmented into three categories: customers (with a sample size of 1006), employees (sample size 1007) and shareholders (sample size 508).

The survey asked respondents their employment status, the sector in which they worked and if they owned shares in any companies listed on the Australian Stock Exchange directly, shares through an index fund, or a privately owned business or trust. We then categorised respondents based on those answers and which group was most behind its target.

Those employed in a privately owned business qualified as ‘Employees’ and those whose owned shared outside of a superannuation fund qualified as ‘Shareholders’. Those who didn’t qualify for either category were categorised as ‘Customers’ because it was safe to assume nearly everyone is a customer to some extent, and the vast majority of people consume goods and services produced by large corporations. If anyone in the sample has successfully managed to live off the grid, their responses are unlikely to have a real impact on the results.

Once the categories for the shareholder and employee surveys were filled, additional respondents were also categorised as ‘Customers’ regardless of their responses to the questions about their employment and investment portfolios.

Redbridge used rim weighting to apply interlocking weights for age, gender, education and location. The efficiency of these weights was 84%, providing an effective sample size of 2,128. Based on this effective sample size, the margin of error (95% confidence interval) for a 50% result on the full sample is ± 2.1%.

Sample breakdown

| Generation | Shareholders | Employees | Customers | All Groups |

| Generation Z | 12.0% | 16.5% | 9.4% | 12.8% |

| Millennial | 28.7% | 35.7% | 23.4% | 29.4% |

| Generation X | 23.2% | 29.9% | 22.1% | 25.4% |

| Baby Boomer | 32.7% | 17.5% | 41.9% | 30.3% |

| Silent Generation | 3.3% | 0.4% | 3.2% | 2.1% |

| Gender | Shareholders | Employees | Customers | All Groups |

| Men | 66.5% | 44.6% | 44.0% | 48.8% |

| Women | 33.5% | 55.0% | 55.4% | 50.8% |

| Location | Shareholders | Employees | Customers | All Groups |

| Inner and middle suburbs | 33.7% | 36.7% | 18.1% | 28.7% |

| Outer suburbs | 26.6% | 34.8% | 26.1% | 29.7% |

| Provincial cities | 21.7% | 13.8% | 26.8% | 20.6% |

| Rural communities | 18.1% | 14.7% | 28.9% | 21.1% |

| Education | Shareholders | Employees | Customers | All Groups |

| Less than year 12 | 8.9% | 7.8% | 16.8% | 11.6% |

| TAFE, trade or vocational | 36.4% | 34.3% | 44.5% | 38.8% |

| University degree | 40.4% | 43.2% | 19.6% | 33.2% |

| Year 12 or equivalent | 14.4% | 14.7% | 19.1% | 16.4% |

| Sector | Shareholders | Employees | Customers | All Groups |

| Other | 1.4% | NA | 5.1% | 2.3% |

| Non-profit | 2.2% | NA | 5.2% | 2.5% |

| Public sector | 17.3% | NA | 20.1% | 11.5% |

| Private sector | 39.0% | 100.0% | 4.6% | 49.6% |

| Own business | 6.9% | NA | 9.6% | 5.2% |

| Business size | Employees | All Groups |

| Fewer than 10 people | 14.2% | 5.7% |

| 10-100 people | 36.0% | 14.4% |

| More than 100 people | 49.8% | 19.9% |