Sir Winston Churchill once said of Russia that its future actions were ‘a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.’ The same can be said of aspects of China’s reemergence—in terms of its capabilities and more importantly of its strategic intentions. Chinese literature and history has long emphasised concealment and deception as an important tactic of statecraft. Yet China is much more an ‘insider’ in the global economic system than the Soviet Union ever was, and its interests are much more compatible with the West’s than Russia’s have ever been. While many experts sensibly see China evolving into much more of a ‘strategic stakeholder’ in the existing regional and global economic and political system, suspicions about its longer-term intentions remain.

The Pentagon’s 2005 Annual Report to Congress on China commented that ‘the outside world has little knowledge of Chinese motivations.’ Subsequent reports implicitly offered the same conclusion. The ramifications of China’s reemergence are sometimes characterised as choices between two polar opposites: ‘threat’ or ‘opportunity,’ strategic ‘competitor’ or strategic ‘partner.’ Many believe that the truth is somewhere in between. Yet, accurately deciphering Chinese strategic intention has a huge bearing on the way we seek to shape the future of our region.

We remain uncertain largely because of seemingly contradictory Chinese perspectives about its place and standing in the world. For example, while China’s leaders and elites tell us that their country wants to integrate peacefully into the existing US-led regional and global order, they also speak about reversing its ‘century of humiliation’ at the hands of Western and Japanese powers and returning China to greatness.

This paper examines the thoughts of some of China’s leading strategic thinkers and policymakers. It shows how China’s leaders and thinkers view the world and China within it, and how they view ‘power’ and seek security within the system. It also shows how their fears and modern goals are deeply conditioned by the interpretation of their own history. Although there is disagreement on some matters, the thoughts of its strategic thinkers are remarkably clear and consistent: the issue of China–US relations dominates current Chinese strategic thinking. Authoritarian China remains a deeply insecure power existing in an American-dominated liberal system, and firmly sees America as a ‘strategic competitor.’

However, China is also pragmatic as a rising power. Well aware of its own vulnerabilities and weaknesses, China seeks to rapidly increase what it terms its ‘comprehensive national power’ (CNP). In doing so, it needs a stable environment and seeks peaceful engagement with the West and especially America in the foreseeable future. This is why it has gone to great lengths to refute the ‘China threat’ thesis. But China is also a clever, ambitious, and proactive strategic competitor. While avoiding overt confrontation, China uses a variety of tactics to circumvent, undercut, bind, and reduce American power and influence.

Future developments might persuade the Chinese that a cautious and measured approach to becoming a great power is not their best option. But for the moment, economic and domestic factors give China an overriding interest in peace—it is a major beneficiary of the current international order. Yet for other reasons, explained in the paper, it remains profoundly suspicious of the West. This explains why China behaves as a largely cooperative rising power but is also a disruptive and subversive one.

In examining the recent evolution of thinking of China’s leaders and strategic thinkers, as this paper does, there is a strong case to be made that modern China is the most self-aware and analytical rising power in history.

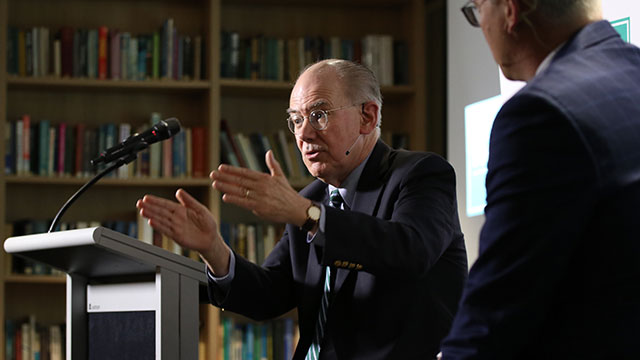

Dr John Lee is a Visiting Fellow at The Centre for Independent Studies.