China’s global media influence has encountered increasing pushback from numerous countries. This report looks at the perception of China’s influence and examines how China is compared to the US in the region in terms of public opinion. Specifically, to what extent people in Australia and East and Southeast Asia perceive China and the US to be favourable or unfavourable to one’s own country, taken as a social base in understanding a country’s pattern of response to China’s global media campaign. It is in this context that the magnitude and outcomes of the local responses to the encroaching soft and coercive power of China can be assessed more effectively. In light of this approach, the findings from the most recent surveys of the Asian Barometer, Pew Research Center and Freedom House are collected and examined. Policy suggestions are provided for strengthening local resilience toward China’s global media influence.

Executive Summary

A rising China is keen to lead and exert extensive influences on global affairs. Its campaign of global media influence represents a unique way in building extremely powerful government agencies to realise the high hope of rejuvenation of China to global greatness.

Global pushback against the hegemonic ambition of China is not because of China’s lack of communication clout in challenging the narratives of the dominant Western powers. It is derived primarily from irreconcilable disagreement in value priorities, basis of political power, and human rights between an authoritarian China and liberal democracy.

Responses to China’s global media campaign vary in efforts across countries. Variation as such can be shown by looking at individual countries’ level of perceived influence from China using meticulous data. China, when evaluated alone, is considered favourable in regard to its influence in Australia and most countries in East and Southeast Asia (except South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam). This report provides analysis and discussions in the context of these countries.

When China is juxtaposed with the US, the general public in Australia and East and Southeast Asia do favour a stronger economic tie with the US over China in an either-or situation (except Singapore). Efforts in pushback are most substantial in Taiwan and the US. Australia has built up resilience against China’s global media campaign. Other concerned countries are relatively short of strength in their response.

Policy suggestions for strong resilience are: 1) Protection of independence and professionalism of news reporters; 2) Diversification of sources of knowledge about China; 3) Support for active civil societies to play a larger role for local resilience; 4) Developing appropriate policies to hinder misinformation with more inter-state cooperation; 5) Clarification of the goals of pushback for more global support.

China has been waging a global influence campaign across the globe. It is better understood as a strategic use of media technology and government resources allocated by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in seeking to effectively influence media content and industries in targeted countries. It aims at changing global opinions and policy discourses in favour of its development model, patterns of managing inter-state relations, and justification of its prospective hegemonic status worldwide. Pushback actions against this effort of China have been occurring across many countries, however. It becomes a collective call as of today, whereas it was merely scattered responses by a few governments or societies in the beginning of President Xi Jinping’s first presidential term starting in 2012. As the saying goes, there is no smoke without fire. What is that specific fire that incites global pushback?

There have been numerous analyses of the ‘causes’ explaining the reasons against an authoritarian China’s abuse of trade, technology, human rights, to name a few from its long list of coercive behaviours in international relationships. One frequently used tactic by the Chinese government is access of its domestic market. Australia is no exception and has been experienced this sort of economic punishment since 2020, owing to the dispute over the call for independent COVID investigation on China. Other leverages that China has used elsewhere show a similar underlying logic.

Under the appearance of China’s use of political and economic tactics, there lies a fundamental motive. Highlighting this essence helps better understand what had been observed of China’s activities at the global level, which in turn have incurred pushback as we see at this moment as a global collective action. This motivating force is a solid belief in Chinese exceptionalism. First and foremost, China has its own unique history in pursuing modernisation. This recalls particularly a bitter history of suffering from the western imperialist and militaristic aggression for a century, before the CCP won the civil war against a corrupt Nationalist government and established a socialist state that ruled the most populous country in the world. Second, China’s socialist path towards modernisation differs from the West. For the CCP, to successfully achieve this goal, power needed to be centralised by the state, rather than adopting a western model of democracy and market institutions in which the state played a lesser role. Third, the ultimate aim of modernisation is to realise a ‘China Dream’. In the words of President Xi, this ambition is not merely to achieve high income as western wealthy countries have done, but to become a “strong state” with a dream of building a strong army (qiáng jūn mèn,強軍夢). The China Dream represents a unique pattern of state-building. It is, for the leaders in the CCP, the only path to realise the high hope of a rejuvenation of China to global greatness.

A strong China, historically, forged a hierarchical order with neighbouring states being subordinated merely as a vassal. China had not been used to dealing with other states in a relationship like the Westphalian system of equal sovereign nation-states. China tended to see itself as a father of the family, with an unquestionable authority over neighbouring states. The latter, however, had sought a sibling relationship with China but in vain. The China Dream, to a large extent, is a modern version of an inter-state relationship of traditional China: the emperor is the gravitational centre, while smaller, weak states orbiting around it offer tributes in exchange for peace and safety.

What makes the Chinese Dream distinct from the traditional tributary system is that in the global era, China expands its influence and interests in a way that incurs extreme tension, doubt and worries far beyond its borders. It is not merely because of its high competitiveness in manufacturing, or its vast economic size that has grown in a shorter period and overpassed developmental states praised in the last century, like Japan or Germany. One fundamental reason is that it champions the neoliberal world order in which Western countries have formed a hegemonic collation, in which an array of lower income countries have been benefiting from their participation in a global production chain as well as accessing the markets in North America and the EU.

The rise of China has generated various responses, the patterns of which in Australia and states in Asia will be presented in the next sections. China certainly is pursuing hegemonic power by becoming a main supplier of finance, infrastructure, technology, and so on. To realise this ultimate mission, a plethora of supporting projects have been established, including the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Belt and Road Initiatives, and the Confucius Institutes. These can be seen as a tool kit of statecraft for generating a ‘natural’ convention of accepting China’s supreme authority in a new global order. The global media campaigns of China are one major part in this whole enterprise.

An up-trend of pushback to this hegemonic ambition of China is indicative of its limitation. One explanation is that China lacks the communication clout to challenge the narrative of the dominant Western hegemon. A perspective, as such, places the problem on weak public diplomacy by China. The solution therefore lies simply in finding more efficient and less controversial instruments to improve persuasion and increase the size of followers. However, the root of the problem from Chinese exceptionalism is much deeper than being maladroit or clumsy in rhetorical performance. It is understandable that a rising China is keen to lead and exert grand influences on global affairs. Yet it is less clear on what basis this power ambition can be justified and validated. All powers aspiring to become a hegemon need to stand on a moral high ground, truthfully expressing a determination to promote common goods for other populations. This forges a solid value basis on which to facilitate the attainment of agreement, trust, and legitimacy of leadership. For the general public, this morality can become as natural as a DNA ingrained in body. A sense that what has been achieved by this hegemon for other countries is natural and right accomplishes two important jobs: first, it shows the way to true common good, so that alternative discourses are prevented from common thoughts; and second, it functions to constrain an all-out pursuit of self-interest at the expense of followers.

China’s exceptionalism may serve as a ground for soliciting sympathy and support for its unique model of economic growth, considering its long history of hardship and underdevelopment for which Western imperialist exploitation has been partially responsible. However, for many governments in the neoliberal camp, the use of economic resources and political power by today’s CCP causes doubt rather than build trust in its ascendancy to a real global power.

The list of complaints is long. Most notable, among others, are the unilateral breach of the Sino-British Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong and criminalisation of civil dissents against the extradition law; a continuous hawkish threat of military force against Taiwan asserting sovereignty; coercive suppression of Uyghurs in Tibet in the name of fighting Islamic extremism; claiming to regain territories lost in earlier eras of foreign aggression, including the South China Sea, and border disputes with India, Japan and Russia; a campaign of big loans and grand projects which are raising widespread concern of new colonialism in Africa. Either close to home or distant outside Asia, China’s grand strategy seems to attempt a cosmopolitan order replicating a world ‘all under the heaven’ at its mandate. It is more about China’s realisation of interest and past glory. However, evidence that common good is being realised is thin.

Various activities of today’s China, ranging from establishing funds for regional infrastructure / investment, through military contentions with border countries, to extensive media campaigns has been forcefully executed. All these geopolitical and economic activities, as well as numerous works for its public diplomacy, can better be understood as a new motive to alter China’s role in the globe. A rising China shows an ambition of becoming a ‘global power’ and demands a role much larger than being the ‘world factory’, as it played in earlier decades when its main policy goal concentrated on accessing capital, technology, and markets overseas for its take-off. Advanced countries in the West as well as in East Asia were offered opportunities in using its cheap labour and lower production costs. Indeed, a substantial trade surplus with China had been appreciated in Japan, Taiwan, South Korea and some Southeast Asian countries. This model of economic exchange between China and the world is passé. Now, it is a head-to-head competition for dominant influence over the global economy and geopolitics.

The tense relationship between China and the liberal democracies of today accounts much for the current pushback from the latter. Competition for geopolitical power can be an easy interpretation. Yet, this viewpoint gives only a partial picture. Rising powers always seek for greater respect, substantial influence and material interests, which necessarily challenge the existing superpower. There is something more fundamental — it is incompatible divergence and disagreement in both institutions and values that should be looked into for a more credible explanation.

A China ascending to the status of the supreme world power foreshows an authoritarian regime which would dismantle democracies and support and strengthen illiberal governments. An autocrat has strong interests in preventing democracy and values like freedom, equality, or justice from thriving within its mandatory sphere. This would entirely change what citizens in the neoliberal camp had considered to be their best way of life. This confrontation is, conceptually, not a version of a clash of civilizations. It is not a conflict that originates from fundamental differences based on regional conventions or group-specific cultures. It is more about irreconcilable disagreement in value priorities, basis of political power, and priority of human rights.

If China replaces the US as the superpower it has long wanted to be, there would be a huge social and cultural counteraction from the liberal world. This scenario would impact greatly on how economic resources would be redistributed and how future prosperity could be maintained. There is no possible accord in insight. This is the main reason why the Chinese exceptionalism and its global influence is seen, not as a model to learn, but as a problem to really worry liberal democracies.

China’s Influence in Australasia: Findings from Large-Scale Surveys

Looking from all angles, a rising China to seize global power is a geopolitical spectacle. A detailed pattern of perceiving the rise of China can be obtained by way of analysing meticulous data. This section uses recent cross-national surveys to compare Australia and countries in East and Southeast Asia. The results from these cross-national polls show, first of all, the current status of China in global public opinions. It might not directly indicate whether and to what extent the Chinese media influence has had an impact on the poll results. The analysis in local contexts provides a detailed structure of what people think about China. It serves as a critical point of departure for evaluation of its influence in future trends.

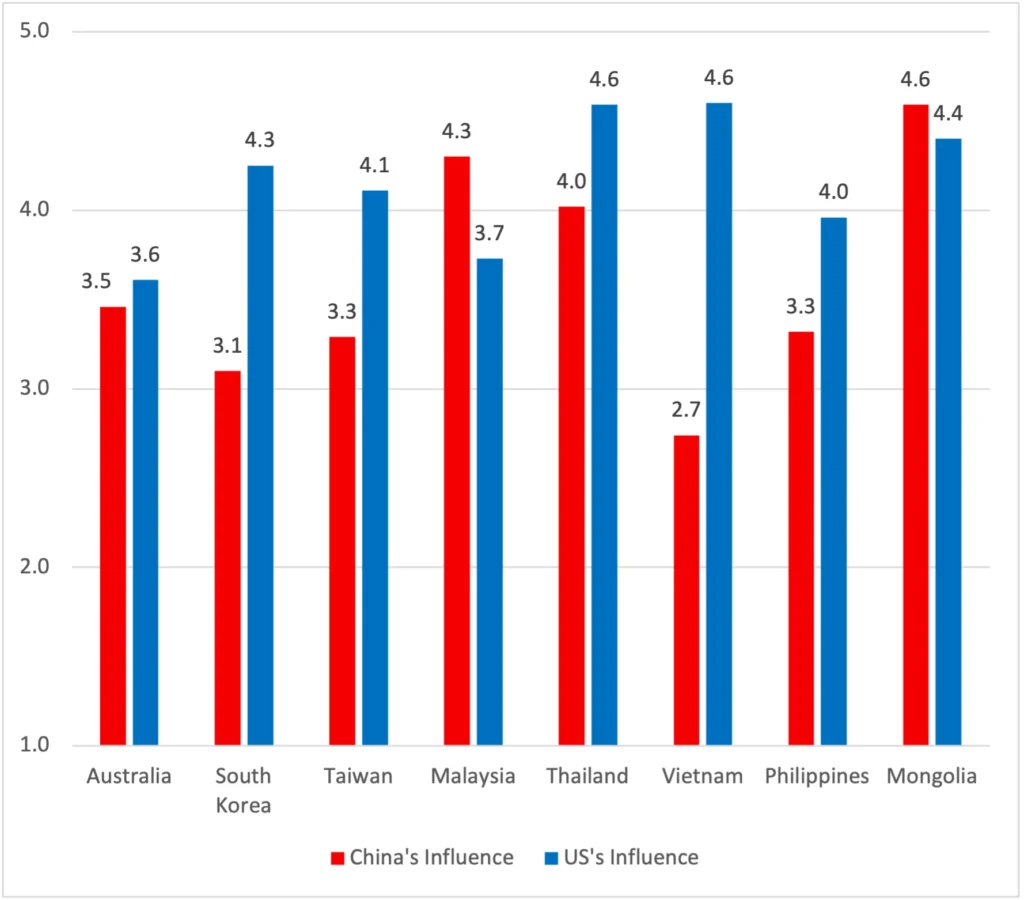

The first issue is concerned with how favourable China’s influence is on one’s own country. The importance of this question is self-evident. But it is more interesting to compare how people simultaneously respond about the influence of the US. Figure 1 shows the results from a most recent Asian Barometer Survey (ABS) implemented in 2018-2019.

Figure 1: Perception of the Influence of China and the U.S.

Original question: “General speaking, the influence the United States / China has on our country is?” Very Positive=6, Very negative=1 (on 6-point scale). Source: Asian Barometer Survey Wave 5 (2018-2019)

Note that the ABS was conducted before 2020, a year in which a series of disputes on trade and export ‘punishments’, accusations of racial abuse, and detention of Australian news reporters by China occurred in response to Australia’s call for an independent investigation of the origin of coronavirus. This context should be referred to in interpreting the survey result for Australia. It was found that Australians were inclined to give a positive evaluation for the two great powers in this survey of 2018. More than half of the respondents nationally said that China had favourable influences on the country. When responding to the question on the influence of the US, they gave a slightly higher score, with an average of 3.6 in favour of the US. Yet, as the two scores are not far above the mid-point (3.5), Australians cannot be strongly marked as pro-American or pro-Chinese in public opinion.

In East Asia, South Korea and Taiwan participated in this survey. They both express a similar pattern in which the respondents are tilting toward the US, while considering China to be potential harmful in influence. Compared to Taiwanese, South Koreans are even more doubtful, with a difference on the two scores equalling 1.2.

When looking at four Southeast Asian countries, there is more divergence than similarity. Thailand appears amiable to both powers, resulting in China receiving a score of 4.0 and the US a score of 4.6. These scores are well above the middle point at 3.5. What is special for the case of Malaysia is that China is favourable (4.3) to a degree higher than the US (3.7).

Vietnam expresses its like and dislike attitudes in a clear-cut manner — Vietnamese show the most assertive view about the influence of the US, and they are not shy from displaying the most negative attitude about China’s influence. The gap between the two evaluations is tremendous at a score of 1.9. It is the widest disparity observed among these eight countries.

The Philippines is somewhat similar to Taiwan regarding the two indicators, with a higher score for the US. This might be not surprising, as both countries have been involved in political and military tension with China. Yet, the Philippines scores slightly lower in pro-American attitude.

Mongolia constitutes a unique case in Figure 1, as it favours China more decidedly than some other countries, as well as the US, trailing only Thailand and Vietnam. It is a ‘like-like’ case in which both great powers are favoured. It is, conceptually speaking, an opposite of the ‘dislike-dislike’ type, with which no country considered here matches. This missing piece can reflect an anonymous tendency of an amiable attitude for the US in this region, as well as favouring the US over China (Malaysia is the only exception).

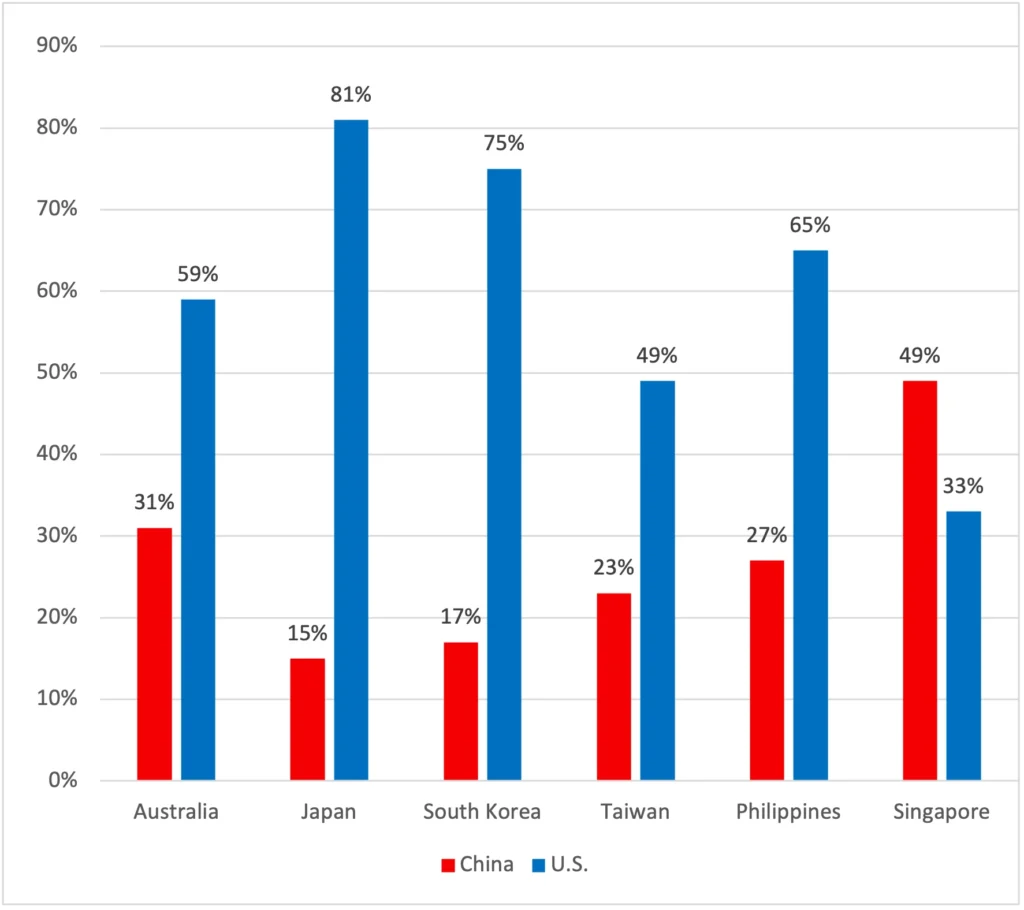

What is favourable often is not the favourite. Results from a recent survey by the Pew Research Center reveals notable disparity in countries concerning economic ties with superpowers. The US and China are placed in an either-or situation of choice by asking this question: “it is important for [nation] to have strong economic ties with China or the United States?” As of 2021, in Australia, about one-third of people ticked China (see Figure 2). However, a substantial majority (59%) embraced the US.

Figure 2: Relative importance of having strong economic ties with China and US (2021). Source: Pew Research Center.

Japan, again, places a high significance with its relationship with the US. In fact, it has the largest majority (81%) in expressing such enthusiasm among the six countries listed in Figure 2, leading to a tremendous difference (66%) for the two sides. South Korea shows a pattern similar to that of Japan, and the discrepancy between the two scores (58%) remains huge.

In a context of having massive investment and trade with China, it would be reasonable to expect Taiwan to show a high recognition of the importance of economic ties. However, this is not what is observed in Figure 2. Only 23% favoured China, whereas almost half ticked the US. In this survey, those who chose both countries made up a substantial proportion at 19%. Such a substantial proportion reveals that there is ambivalence on this island country when it comes to the issue of ties with China. However, it should be noted that compared to a pro-China position, pro-Americanism clearly prevails. This is also what has been observed with the Philippines, where slightly more than one-quarter prefer China, vis-à-vis a large majority (65%) who are assertive that it is more important to have strong economic ties with the US.

Singapore appears to stand out in favouring China over the US. This disposition is a stark opposite of all other countries in the Figure. This distinct pattern may reflect two important underlying factors that (1) Singapore has been the largest foreign investor in the world in Mainland China since 2013, and (2) A large majority of its population is of ethnic Chinese descent (76%). In addition, this attitudinal disposition is in accordance with the government’s pursuit of a special relationship with China, despite being a country also known in the region as one of America’s staunch allies.

For most countries surveyed in Figure 2, China is not considered more favourable when it comes to choosing ties in an either-or situation. Other reports also provide similar findings that people in Northeast and Southeast Asian countries did not cite China as the best ‘future model’. Its institutions and the way it achieved its growth records do not constitute an attraction, whereas Japan appears to be an envy of people in Asia. Even Chinese respondents did not cite China in this context; instead, they favoured the US model. There is consistent evidence across different surveys with regard to a feeling of increased distance with China. An increasingly negative sentiment toward China has also been documented in other reports focusing on Western countries. All in all, globally, the evidence of China being a favourite power is thin.

Local Resilience to China’s Global Media Campaign

In responding to China’s massive, aggressive (and often coercive) campaign for influencing media content and industries globally, pushback by numerous countries have emerged. In this regard, pushback is indicative of the strengths of local initiatives of organised activities to counteract intimidation, cyberbullying, misinformation, or any illegitimate manipulation of social media intended for expanding influence and material interests of a foreign regime in targeted territories. Effective pushback does not come easily. It can be derived only from the building of strong societal resilience, that is, a society that is highly aware of harmful impacts of intentionally spread misinformation and misuse of digital means on trust and social stability, and is capable of building strong institutions to prevent detrimental influences as such.

Vigilance and resilience against China’s influence campaign have increasingly been prioritised in policy agenda by some governments. A few have placed it even at a national security level. Groups and organisations in civil societies, nevertheless, have been positioning themselves in the very front. Not all pushback is equal in strength. Difference in efforts and outcomes has been observable. It is important to know the reasons why some countries are more effective in this than others.

The recent release of the Freedom House’s report on China’s global media influence and local resilience provides a timely, comprehensive review of current pushback across 30 countries. This report, titled Beijing’s Global Media Influence: Authoritarian Expansion and the Power of Democratic Resilience (BGMI), describes how the Chinese government has invested significant resources to encroach local media institutes and to promote particular narratives in its favour in the most recent years under President Xi (approximately 2019-2021). This section will use this rich information to identify strong examples and highlight main characteristics of the best practices. Lessons can be learned from comparing the patterns of resilience by countries that have been forcefully counteracting China’s global media influence.

The BGMI generates two major indexes. The first is measurement of China’s media influence efforts, indicative of “detail overt and covert forms of Chinese state media content dissemination, disinformation, censorship and intimidation, control over content infrastructure, and dissemination of CCP norms and practices”. Based on a qualitative evaluation on 85 items, each country is scored on a scale from 0 from 85. The second is resilience, the score of which show the strength of journalists, civil society and government in counteracting China’s media influence. Its check items include a wide range of 65 activities. Its score was adjusted before summarising it on the same scale as that of China’s media influence efforts.

Figure 3 displays eight countries of interest for cross-societal comparison. Reading it from the left-hand side, Australia is shown to have received a mildly high media influence from China. What makes Australia distinctive is that it has spent a substantial effort in counteracting, trailing only Taiwan and the US. The difference between the two scores is the largest (30) among the listed countries.

Taiwan stands out in the Figure because it scores highest on both fronts. China’s forceful media influence has been on all fronts in this country, using new tactics such as disinformation campaigns and cyberattacks, in addition to provision of paid content and funds, not to mention self-censorship tied in with exchange for business within China. Robust counteracting activities in Taiwan includes both the government and civil societies in monitoring fake news and strengthening independence and freedom of the press. The initiatives from civil organisations are most impressive. Social movements and massive rallies, some of which were crowdfunded, have been organised to mobilise collective pushback activities.

China’s global influence campaigns in Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, India, and Sri Lanka are less forceful than in Taiwan, despite China’s efforts in expanding its weight in local media and opinion formation. This group of countries together feature a somewhat mild response. However, the Philippines and India appears to be more resilient than others in this group, probably because both had recently experienced conflicts on borders with China (the South China Sea dispute and Galwan Valley skirmishes, respectively) which led to increased local vigilance.

In the far-right side of Figure 3, the US reflects the results of strong pushback. China’s tactics, soft or coercive, to influence the US media have been used extensively, including disinformation campaigns, paid inserts in news and local radio programming, subsidised press trips, control over media used by Chinese-speaking communities, among others. However, the US has invested heavily in building a legal infrastructure which enhances alertness of political leaders and government agencies to security challenges posed by foreign media activities. Notable is a robust enforcement which demands transparency in foreign media’s operations and funding, cross-ownership, foreign correspondents’ movements and activities. Like Taiwan, the US is one highly targeted country and has responded more decisively when compared to numerous countries surveyed by the Freedom House.

Figure 3: China’s Media Influence and Local Resilience (source: Freedom House)

Lessons Learned from Public Opinion and Country Responses

The influence of China’s global media campaign can be gauged more meaningfully when compared to the existent superpower, the US. In general, a consideration as such helps prevent undue exaggeration of a challenging power. In light of this comparative approach, it appears that China’s influence has been overrated. This fact has been obscured in previous observations in which China was viewed singly without the US being juxtaposed.

One major lesson from this comparative report is that China’s efforts have been seen as a ‘charm offensive’. From a public opinion perspective, there has been an upward trend of mistrust in China across the surveyed countries. The evidence gathered before the pandemic in 2020 reveals an early onset. The statistics of today show a continuing trend.

The second lesson is that China’s ‘charm offensive’ has received strong pushback, without which the detrimental effect on local media and democracy would be much more serious than was observed. Yet, there is substantial variation across countries in terms of the strength of pushback actions against the tactics used by an autocratic China. China has targeted countries especially where stakes are high, including Australia, Taiwan and the US.

Third, resilience actions are not a knee-jerk reflex and cannot be generated in a short span. Even in countries where strong resilience has been built up, their pushback, often a set of coherent counteractions with extensive efforts from different sources, needs sustained support from both government and civil society.

Fourth, three common features appear in countries equipped with strong resilience: the state’s legal actions, vigilance of active civil societies or organisations, and high level of professionalism and independence of journalists. Government response, particularly through legal infrastructure and effective targeting of problematic media agencies and misinformation, is a necessity. The US and Australia are particularly strong examples in this regard. Robust civil societies for pushback need to involve a wide array of China experts and opposition parties to increase societal awareness of China’s influence campaign. Taiwan appears to be a good model here. Independent journalism plays a critical role in successful pushback. Subsidies from China for correspondents and paid content lead to self-censoring and, in the long run, damages social trust of the press. This is a critical area needing high vigilance because of its detrimental impact on blocking knowledge and hiding true happenings from the people.

Finally, clarification should be made more emphatically that pushback is counteraction targeting mainly the Chinese government’s global media influence. Caution should be exercised to ensure a clear and meaningful purpose. Over-reaction has occurred in some countries and led to increased incidents of discriminatory treatment of Chinese communities.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations for Australia and Asia

Perception of China’s influence and local response to its global media campaign differ substantially across countries. There are country cases showing a determined attitude to push back China in this regard, yet there are others responding with limited efforts. First and foremost, pushback is a legitimate response, not because China is becoming a global power, but because an autocratic government has used its vast economic resources and market access as a political tool. This is a grave concern because of its threat to the ideal of liberal democracy and its fundamental values of freedom, justice and human rights. Also, as the Chinese propaganda voices are being elevated to a higher level, it weakens civil societies by reducing their knowledge of what has happened inside China and its capacity for breaching of human rights and the common good.

Most governments this report is concerned with are still at an early stage in developing appropriate responses. Policy suggestions for pushback on China’s global media influence are:

Protection of independence and professionalism of the media. Media and journalists should receive stronger support in protecting their valued independence and professionalism. Self-censoring for business interests is indicative of intimidation by foreign powers and a warning of erosion of autonomy for correspondents. Governments should be highly vigilant in this regard. The safety issues for news reporters working on China-related news and information deserves a status of priority in citizen protection policies.

Diversification of sources of knowledge about China. Media tend to feature concentration and controls by large holding companies. Diversified sources of knowledge lower the risk of biased, one-sided feeding of misinformation and facilitate critical reporting of what is happening in China’s politics and society. Diversification efforts can include academic research contributions on China. Transparency in China government-linked research and funding should be guaranteed; research ethics for scientists in this regard should be implemented.

Larger role of civil society. Civil society as an active force in pushback should be recognised more supportively. Increasing voluntary involvement from various activist organisations watching China helps enhance transparency in press and academia. The viewpoints and reporting of independent civil groups provide different angles in observing China and enhance a balanced view of it.

Greater digital literacy. Misinformation and fake news originating from China reveals a systemic attempt of the Chinese government in exerting influence on how the nation is to be presented and favoured in local electoral campaigns and policy orientations. Media literacy of the general public can be strengthened to thwart the detrimental impacts of misinformation especially for countries with frail responses.

Clearer Goals for Pushback. The major goal of pushback can be stated clearly —it is a legitimate response against the use of power and resources by an authoritarian Chinese government as it attempts to unduly assert its influence over a foreign state. It should avoid being seen or interpreted as anti-Chinese or pro-American and falling prey to ideological battles. Clear statement of this goal helps reduce undesirable discrimination against Chinese diaspora and their migration and pursuit of opportunities in individual countries.

Australia has stronger performance in curtailing the influence of China on media than most studied countries in East and Southeast Asia. It is suggested that these countries stay alert and work together to forge a cross-nation network in exchange for strategies, organisation, and skills to achieve effective resilience against China’s global media campaign.

References

Michal Walsh, 2021, “Australia called for a COVID-19 probe. China responded with a trade war.” ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-01-03/heres-what-happened-between-china-and-australia-in-2020/13019242.

Xi, Jinping, “To realize a Chinese Dream of Great Rejuvenation of Chinese People.” http://www.qizhiwang.org.cn/BIG5/n1/2020/0628/c433090-31761440.html. (in Chinese)

William Callaham, 2014, “Chinese Exceptionalism and the Politics of History.” In Niv Horesh and Emilian Kavalski (eds.), Asian Thoughts on China’s Changing International Relations. London: Palgrave Macmillan, p.26.

A more recent version kicked off at 2022 by the name of the Global Development Initiative. “Jointly Advancing he Global Development Initiative and Writing New Chapter for Common Development”. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202209/t20220922_10769721.html.

Pratik Jakhar. 2019. “Confucius Institutes: The growth of China’s controversial cultural branch.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-49511231.

Benjamin Tze Ern Ho, 2021, “China’s “Exceptional” Public Diplomacy: Dressing up the Dragon”, in The Frontiers of Public Diplomacy Hegemony, Morality and Power in the International Sphere, edited by Colin R. Alexander. New York: Routledge, pp. 117-130.

Colin R. Alexander, 2021, “Hegemony, Morality and Power: A Gramscian Theoretical Framework for Public Diplomacy.” In The Frontiers of Public Diplomacy Hegemony, Morality and Power in the International Sphere, edited by Colin R. Alexander. New York: Routledge, pp. 9-24.

Lindsay Maizland, 2022, Hong Kong’s Freedoms: What China Promised and How It’s Cracking. Council on Foreign Relations. Down. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/hong-kong-freedoms-democracy-protests-china-crackdown.

Hsin-Hsin Pan, Wen-Chin Wu and Chien-Huei Wu, 2022, “No Room to Move: Public Opinion in Taiwan Offers Few Options on China,” Global Asia, 17(3), pp. 36-42.

Austin Ramzy and Chris Buckley, 2019, Nov. 16, New York Times, ‘Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims.”

The Economist, 2022, May 20th,“Chinese loans and investment in infrastructure have been huge.”

Hal Brands and Michael Beckley, 2022, What Does China Want? Beijing’s Ambitions Are About to Crash into its Problems. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/08/13/what-china-wants-us-conflict.

Jeffrey A. Bader, 2005, China’s Role in East Asia: Now and the Future. https://www.brookings.edu/on-the-record/chinas-role-in-east-asia-now-and-the-future.

Hal Brands and Michael Beckley, Ibid.

Michal Walsh, op. cit.

Laura Silver, Christine Huang and Laura Clancy, 2022, “How Global Public Opinion of China Has Shifted in the Xi Era.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2022/09/28/how-global-public-opinion-of-china-has-shifted-in-the-xi-era.

Topline questionnaire, Global Attitudes Survey. Pew Research Center. June 30, 2021.

See Peng Er Lam, 2021, “Singapore-China relations in geopolitics, economics, domestic politics and public opinion: an awkward “special relationship”? Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 10, pp. 203–217.

Lam, ibid.

Ming-Chang Tsai, 2021, “Will you (still) love me tomorrow: Pro-Americanism and the China factor in Asia,” Asian Journal of Social Science 49, pp. 21-30; Hsin-Hsin Pan, 2020, “Is the USA the only role model in town? Empirical evidence from the Asian barometer survey,” Journal of Asian and African Studies, 55, pp. 73-749.

Jon Henley, 2022, “Sharp fall in China’s global standing as poll shows backing for Taiwan defence.” The Guardian, Oct 23rd. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/23/sharp-fall-in-chinas-global-standing-as-poll-shows-backing-for-taiwan-defence.

Laura Silver, Christine Huang and Laura Clancy. Op. cit.

Sarah Cook, Angeli Datt, Ellie Young and BC Han, 2022, Beijing’s Global Media Influence: Authoritarian Expansion and the Power of Democratic Resilience. Washington, DC: The Freedom House.

Ibid., p. 73.

Wanning Sun, 2016, Chinese-Language Media in Australia: Developments, Challenges and Opportunities. University of Technology Sydney: Australia-China Relations Institute; Fan Yang, 2021, Translating Tension: Chinese-Language Media in Australia. Sydney: Lowy Institute.

Sarah Cook, Angeli Datt, Ellie Young and BC Han, p. 26-27.

Laura Silver, Christine Huang and Laura Clancy. Op. cit.

Luke Buckmaster and Tyson Wils, 2019, Responding to Fake News. In Briefing Book Key Issues for the 46th Parliament.https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BriefingBook46p/FakeNews.

Image courtesy of Jeff Nishinaka Paper Sculpture