Summary: Dealing with the Digital Yuan. Policy choices facing Australia

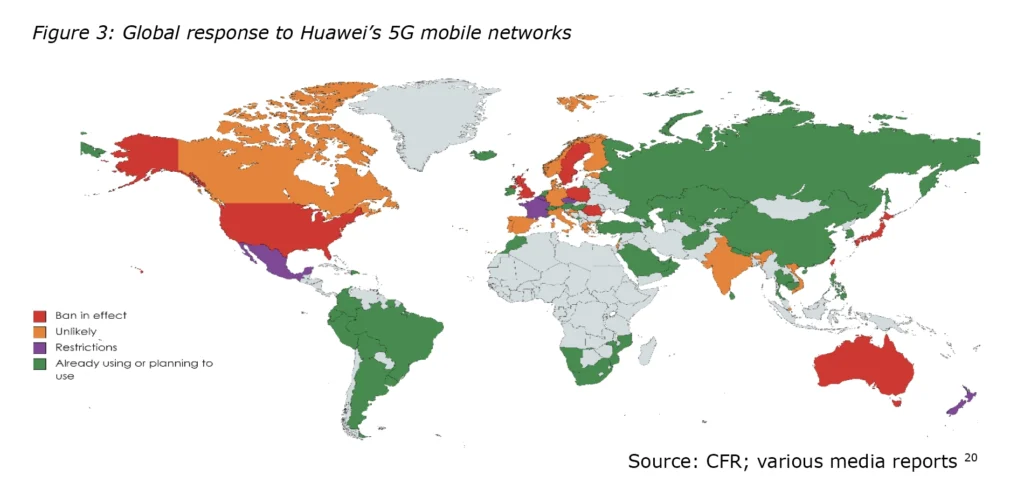

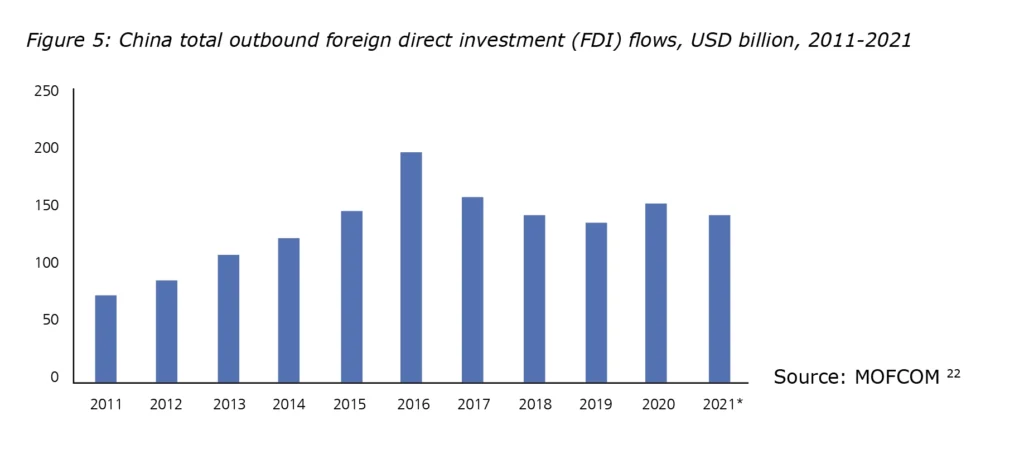

Throughout history, financial innovation has often been a precursor to geopolitical clout or hegemony. From 15th century Florentine innovations in banking to new public debt and equity markets during the ‘Dutch Golden Age’ of the 17th century, financial developments and improvements have played an important role in the rise of states and empires. China is investing extensive resources and capital in developing new financial technology (‘fintech’) rails, platforms and products. The Chinese government believes that unlocking digital value is the key to furthering its technological, economic and geopolitical objectives. While digital payments may not be as tangible as semiconductors nor as controversial as next-generation telecommunications, they play a critical role in shaping international relations, trade, currency dynamics, and economic growth.Australia should be attentive to these developments. Not only is China seeking to lead in fintech technologies, just as it has sought to do with 5G telecommunications and artificial intelligence (AI), it is also attempting to establish new cross-border and international payment systems that could be competitive alternatives to the current US dollar and SWIFT-based systems — leading to more Chinese control over global digital transactions.

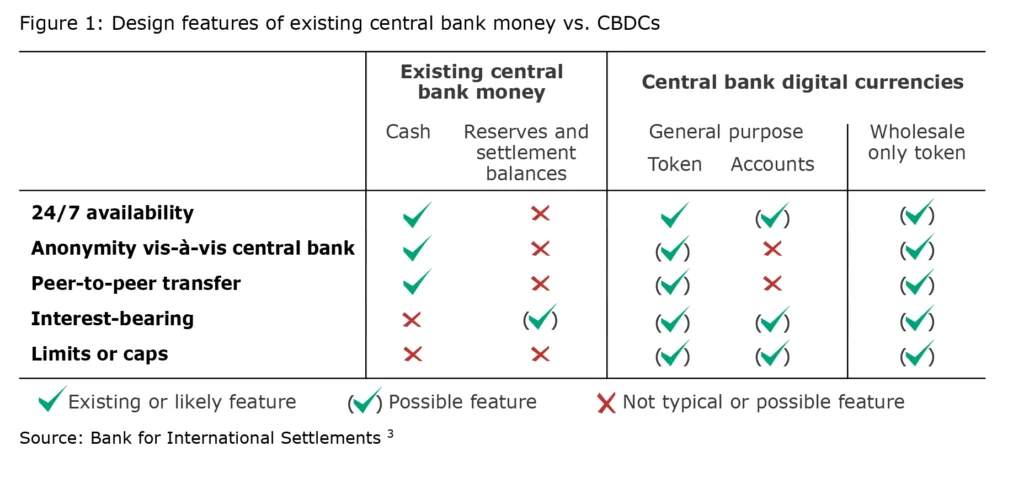

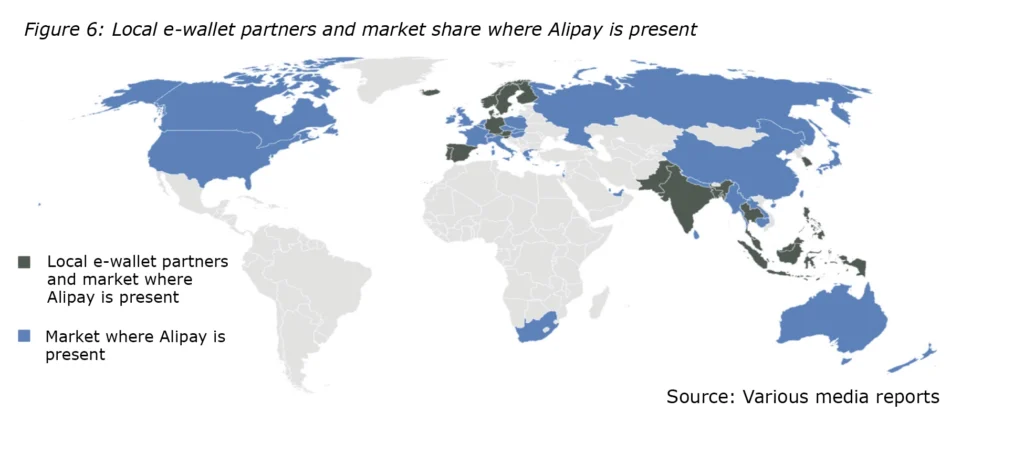

China now has initiatives led by both the state and the private sector to boost the global influence of its fintech capabilities.1 Many of us are familiar with popular Chinese fintech payment platforms such as Ant Group’s Alipay and Tencent’s WeChat Pay, as they are commonly accepted forms of payment for Australian retailers and merchants. Lesser known is the government’s new state-led initiative to create a central bank digital currency (CBDC), known as ‘e-CNY’’ or ‘digital yuan’. A CBDC is a digital form of central bank money, or, in other words, a liability on the central bank that is distinct from traditional reserves or settlement accounts held by commercial banks at central banks.2

If China dominates the future infrastructure of international payments, it will use this as a powerful geopolitical tool with significant implications for the Indo-Pacific region and Australia’s interests in it. First, such an outcome would insulate China from the risk of US sanctions, which today serve as a significant form of leverage and check against China. Second, it would give China’s government a powerful lever for imposing its own sanctions or coercing smaller countries in the region. For instance, China could use programmable digital money to force countries to use e-CNY transactions and holdings in certain ways, freeze assets, or prevent access to any individual, company, or country it wanted. Third, Australia and other countries could be forced to accept e-CNY due to the sheer magnitude of Chinese trade and commercial interests. Fourth, it may lead other countries including Australia to develop and roll out their own central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) as alternatives or complements to e-CNY in a way that could change the global financial system as we know it.Given Australia and other major Western democracies have expressed concerns about the rise of China in the realms of 5G telecommunications and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, they should not neglect the strategic significance and implications of e-CNY. The e-CNY in its current design and application effectively allows the Chinese government to monitor, trace, and potentially manipulate all financial and payment data within China. The technology as it now stands also gives the Chinese government the potential to use these capabilities on cross-border payments and trade settlement involving China in the future. Chinese ambitions to expand fintech influence through domestic private tech companies and the state-led e-CNY have already provoked a wave of digital protectionism in the West and in advanced economies in the Indo-Pacific. Australian policymakers should study these dynamics and evaluate best-practice approaches to navigating relations with China in the field of financial technology.

This paper is divided into four main sections. Section 1 defines e-CNY and provides an overview of the current research on the topic. Section 2 examines China’s regional fintech presence primarily in the Indo-Pacific. Section 3 establishes future trendlines for e-CNY and its potential impact on global FX and trade flows. It also explores how e-CNY could impact renminbi (RMB) or yuan internationalisation and US- dollar dominance. The final section will outline a list of policy recommendations for Australian policymakers in response to the growing use of e-CNY.

(1) What is the e-CNY, or digital yuan?

Definition of e-CNY

China has already launched the world’s first major central bank digital currency (CBDC), known as e-CNY, in its domestic market. The e-CNY in its current form is aimed at centralising control of data, facilitating international trade and potentially increasing RMB usage in the global financial system in the future. In technical terms, the e-CNY is a token-based retail central bank digital currency running on a two-tiered centralised ledger network controlled by China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC). Chinese retail banks and third-party payment platforms act as intermediaries. Settlement ultimately happens in digitised RMB, which will ultimately replace the monetary base (M0) and all cash in the economy.

Following six years of research and two years of piloting, e-CNY is now in use in around 23 pilot cities across China, including Beijing, Shenzhen and Shanghai. Seven Chinese commercial banks and two payment providers, WeChat Pay and Alipay, can now provide e-CNY for QR code payments, remittances, and peer-to-peer (P2P) payments. According to government data, total transactions of e-CNY from December 2019 to August 2022 reached RMB 100 billion. 4

In its current iteration, e-CNY is used for high-frequency domestic retail purchases, and it enables payments without an internet connection or a bank account via dual offline technology using linked smartphones.5 It can currently enable 10,000 transactions per second (TPS), with the capability of reaching 300,000 TPS as the upper limit. This figure is still below private payment providers WeChat Pay and Alipay’s capabilities but considerably higher than US card provider Visa’s (at 1,700 TPS). 6

Nevertheless, Beijing has larger long-term strategic objectives in launching e-CNY. These objectives primarily revolve around creating alternative cross-border payment and settlement systems that could remain less visible to US authorities and less vulnerable to sanctions. Chinese officials plan to internationalise the e-CNY by working with foreign central banks to increase interoperability with the e-CNY. It is possible, however, that in the future foreign consumers or merchants in less financially and technologically advanced countries could be paid in e-CNY via e-CNY accounts at a Chinese bank or a third-party payments provider. The appeal of digital currencies like the e-CNY is that they enable rapid, low-cost payments. This differs from traditional banking transfers, which take days to clear and charge high fees.

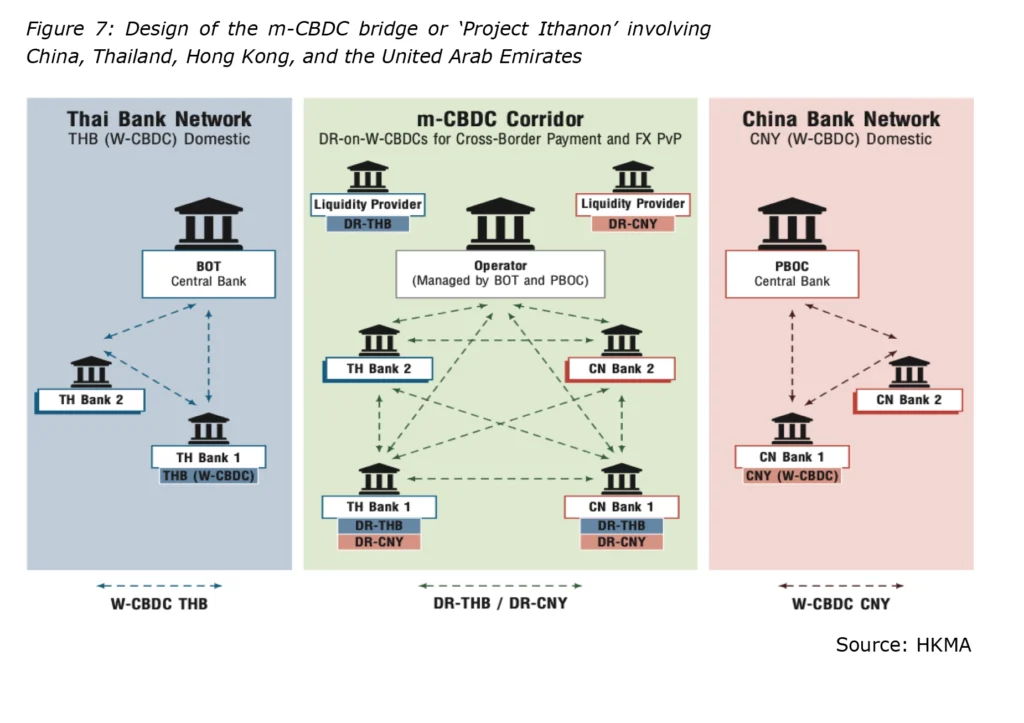

In developing countries with weak banking systems, digital currencies are even more attractive. The PBoC long-term strategy is to convince other countries’ central banks to develop digital currencies that are interoperable with China’s e-CNY via central bank-to-central bank bridges. The establishment of such ‘bridges’ between central banks, known as m-CBDCs, is critical to RMB internationalisation, as this would allow a large volume of transactions and seamless conversions between currencies. Developed countries such as Japan, Canada, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Singapore have already shown interest in developing multi-country central bank bridges for processing digital currency transactions, though not necessarily with China. Only Thailand, Hong Kong, and the United Arab Emirates are actively working with China on such bridges. These bridges could enable Chinese consumers to pay foreign merchants with e-CNY and for the merchants to receive the funds in their local currencies via local banks that would perform fast currency exchange. Hong Kong’s Faster Payment System is already developing these capabilities.

Literature review

Current research on e-CNY demonstrates growing interest in the fields of Chinese fintech, central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) and cross-border fast payments. A rising number of university and think tank entities has written on the subject and collated valuable data on e-CNY usage. The Atlantic Council, Hoover Institution (Duffie et al., 2022) and Bank of International Settlements have published several of the most prolific and in-depth studies into e-CNY. 9 The People’s Bank of China (PBoC), which has led the research and development of e-CNY itself, is also a vital resource for white papers and an invaluable window into Chinese policymakers’ objectives and intentions. 10

Academics in the fields of computer science (Shen and Hou, 2021) 11, finance and economics (Chorzempa, 2021; Prasad, 2021; Xu, 2022; Huang, 2022; Uchida, 2022) 12, and international relations and public policy (Fullerton and Morgan, 2022) have also published significant work on the topic. 13 Many academics have chosen to focus on the implications of e-CNY for U.S. dollarisation or U.S. dollar hegemony, a reflection of American policy-makers’ concerns about China’s fintech capabilities in the midst of an expanding U.S.-China tech war (Prasad, 2021; Chorzempa, 2021; Aysan and Kayani, 2022).14

There is growing interest too in examining the regional and geopolitical implications of e-CNY beyond the question of U.S. dollar dominance, although the pool of research has been more limited given e-CNY’s relative nascency and the early concentration of research in the U.S. (Randhawa, 2020). 15 Previous work on RMB usage in the Asia-Pacific, financing in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the development of the petroyuan provide useful frameworks for further developments in this area (Shu et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2017; Matthews and Selden, 2018). 16 The broader discussion of central bank digital currencies interlinking and cross-border fast payments (Lucido, 2020; Agur et al., 2019) is also worth exploring when considering likely trendlines for e-CNY’s development within the greater global ecosystem for cross-border payments and financial flows (Boar et al., 2021).17

This report will endeavour to bring together these different perspectives and contribute to the existing literature by establishing the regional implications and potential trendlines of e-CNY expansion in the Indo-Pacific.

Threats posed by e-CNY

Foreign governments have increased their scrutiny of Chinese fintech platforms including both private fintech companies and the state-run e-CNY. There is a growing recognition worldwide that Chinese tech platforms, whether private or state-run, pose a risk to a state’s domestic data security and privacy, and might even be used to enhance the influence of the Chinese state abroad. In September, the Chinese government issued provisions in the ‘Opinion on Strengthening the United Front Work of the Private Economy in the New Era’, which called for increasing hiring of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members within the companies for enhanced surveillance.18 The Chinese government’s crackdown on Chinese tech companies since November 2020 has forced fintech companies to form financial holding companies. Chinese tech firms have also been fined for anti-competitive behaviour and insufficient data security and privacy protection by internet platforms. As a result, Chinese tech companies have been forced into obeisance to the party line.

Furthermore, other states are also focusing on the ways that China’s state-run digital currency, e-CNY, will dramatically strengthen China’s domestic techno-authoritarian model, while facilitating the export of this model overseas in more authoritarian-leaning countries. Through a combination of e-CNY and China’s Social Credit System, the Chinese government could financially isolate and punish critics and dissidents including journalists, intellectuals, and ethnic minorities. Additionally, the centralised ledger system (i.e., stored and operated by the People’s Bank of China) could be used to preferentially benefit Chinese companies, as the great firewall of China has done domestically. Data privacy and security risks to foreign entities will intensify, because all financial data will be accessible to the Chinese government, pursuant to China’s 2017 Cybersecurity Law and the new 2020 draft Data Security Law. 19

(2) China’s fintech presence in the Indo-Pacific

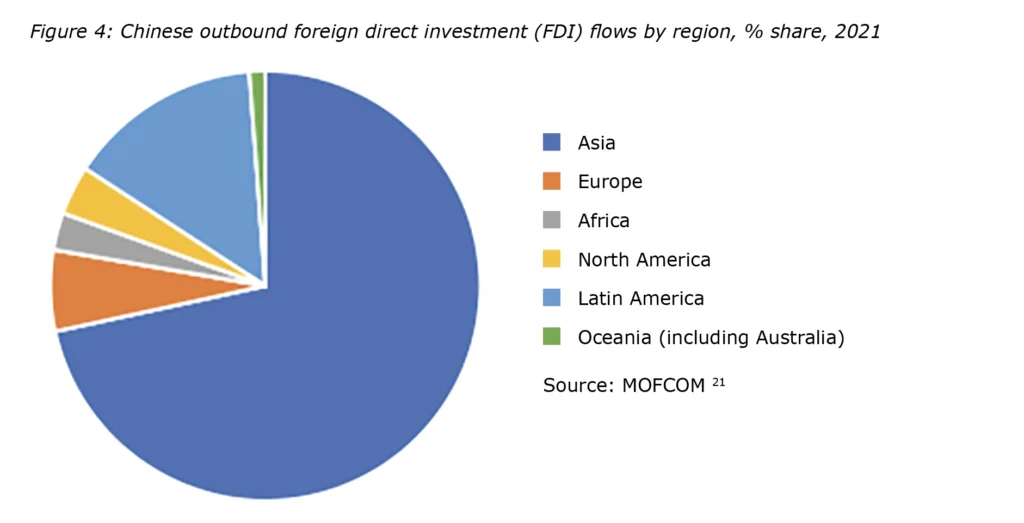

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the overseas acceptance of Chinese digital payment methods was driven by Chinese outbound tourism flows and via partnerships with foreign merchants seeking to capture Chinese consumption. From 2012 to 2018, Chinese tourists were responsible for around a fifth of the world’s total spending on tourism. 23 Chinese tourists’ overwhelming preference for mobile payment methods driven by their easy cashless alternatives at home has encouraged foreign countries and their merchants to accept Alipay, WeChat Pay, and UnionPay QuickPass QR-based payment methods. While foreign merchants were quick to use Chinese payment methods to attract Chinese shoppers, foreign consumers were slow to adopt Chinese payment methods. Alipay also expanded internationally by funding and providing technological expertise to local fintech companies to replicate Alipay’s success abroad and connect their systems with Alipay’s via a network of e-wallets (e.g., South Korea’s Kakao Pay and Indonesia’s DANA) covering 10 countries. The plan was to make Alibaba-linked e-wallets such as India’s Paytm and the Philippines’ GCash operable outside of their local markets and in countries covered by Ant’s merchant and payment partnerships.

The Indo-Pacific remains the most developed market for fintech and cross-border payments, and is therefore the region that private Chinese tech companies have targeted the most aggressively. The majority of Alipay’s e-wallet partners are located in Asia (i.e., India’s Paytm, Thailand’s TrueMoney, Korea’s KakaoPay, Philippine’s GCash, Hong Kong’s AlipayHK, Malaysia’s Touch’nGo, Indonesia’s DANA, Pakistan’s Easypaisa, and Bangladesh’s, bKash). Moving forward, Chinese private and state-run platforms (i.e., e-CNY) will most likely continue to gain ground against traditional payment systems across Asian emerging markets (EMs), with Chinese demand being a main driver.

For now, this private-led fintech internationalisation effort has stalled. As of 2020, only 0.5 per cent of Ant’s payments are international. 24 A plan initiated in 2019 to connect these e-wallets in a global interoperable network was shelved in late 2020 as the company faced pressures from domestic and foreign regulators. The original plan was to make the partnering local e-wallets, such as India’s Paytm and the Philippines’ GCash, operable outside of their local markets and in countries covered by Ant’s merchant and payment partnerships. Similarly, Tencent’s WeChat Pay also largely failed in its attempt to capture foreign users directly through its WeChat e-wallets. Chinese private fintech giants have largely failed to achieve global dominance and interoperability in peer-to-peer and small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) transactions.

Currently, Chinese policymakers plan to internationalise the state-led e-CNY by working with foreign central banks to increase interoperability with the e-CNY. The PBoC’s focus is convincing other countries’ central banks to develop digital currencies that are interoperable with China’s e-CNY via central bank-to-central bank ‘bridges’. The establishment of such ‘bridges’ between central banks is critical to RMB internationalisation, as this would allow a large volume of real-time cross-border transactions and seamless conversions between currencies. These transactions could be much more easily protected from US sanctions because they would be far less visible to US regulators.

Developed countries such as Japan, Canada, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Singapore have already shown interest in developing multi-country central bank bridges for processing digital currency transactions, although not necessarily with China. Only Thailand, Hong Kong, and the United Arab Emirates are actively working with China on such ‘bridges’.

Even without central bank-to-central bank ‘bridge’ infrastructure, it is possible that in the future foreign consumers or merchants in less financially and technologically advanced countries could be paid in e-CNY via e-CNY accounts at a Chinese bank or a third-party payments provider. The appeal of digital currencies like the e-CNY is that they enable rapid, low-cost payments. This contrasts with traditional banking transfers, which can take days to clear and charge high fees. In developing countries with weak banking systems, digital currencies are even more attractive. As with the private-led wave of fintech expansion, it is highly probable that the first wave of foreign e-CNY adoption takes place in the Indo-Pacific due to strong trade, investment and tourism flows with China.

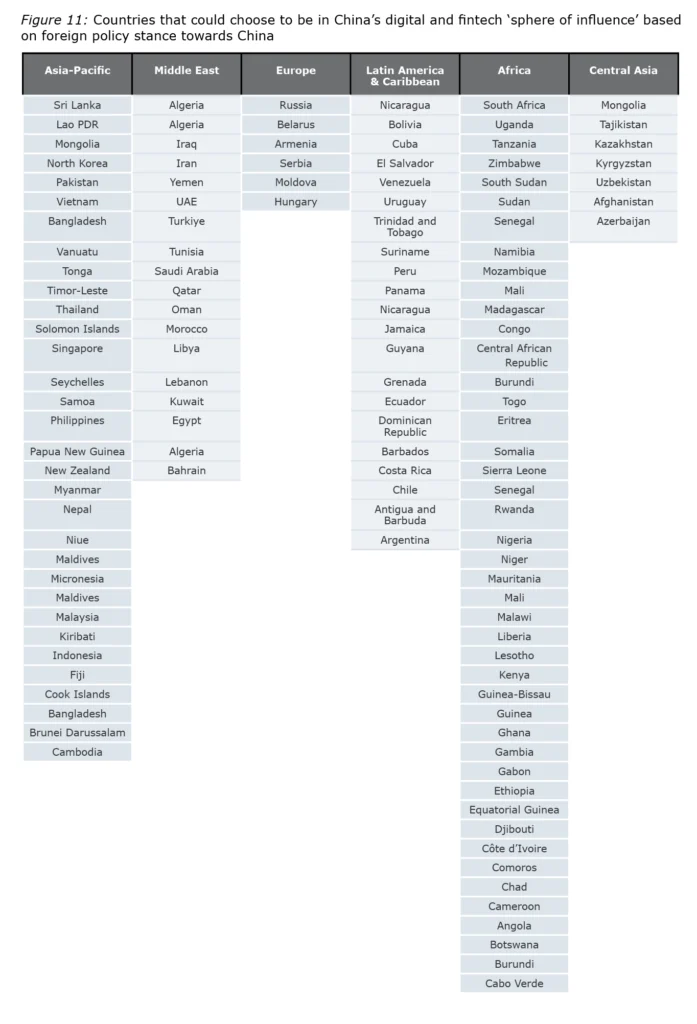

In the future it is conceivable that foreign banks could also choose to work directly with the PBoC to give e-CNY access to foreign consumers and merchants. According to Chinese reports last August 2021, three foreign banks are planning to access e-CNY through a private clearing platform built by Shanghai’s City Bank.25 China’s dominance in providing smartphones and telecommunications equipment to developing nations makes it easy to push apps that use e-CNY. Chinese telecommunications conglomerate Huawei is already a strategic partner to the PBoC’s Digital Currency Research Institute. New Chinese phones will come with an e-CNY wallet, for instance. As the February 2022 Beijing Olympics showcased, foreigners in China can already create their own e-CNY wallets without a Chinese banking account (though single transactions are extremely low for these accounts — around $1500 and $300, respectively). By encouraging other countries to develop technology stacks that resemble China’s or are interoperable with Chinese systems, the Chinese government can conceivably create a new digital ‘sphere of influence’ through which to project power and protect its strategic interests.

In the future it is conceivable that foreign banks could also choose to work directly with the PBoC to give e-CNY access to foreign consumers and merchants. According to Chinese reports last August 2021, three foreign banks are planning to access e-CNY through a private clearing platform built by Shanghai’s City Bank.25 China’s dominance in providing smartphones and telecommunications equipment to developing nations makes it easy to push apps that use e-CNY. Chinese telecommunications conglomerate Huawei is already a strategic partner to the PBoC’s Digital Currency Research Institute. New Chinese phones will come with an e-CNY wallet, for instance. As the February 2022 Beijing Olympics showcased, foreigners in China can already create their own e-CNY wallets without a Chinese banking account (though single transactions are extremely low for these accounts — around $1500 and $300, respectively). By encouraging other countries to develop technology stacks that resemble China’s or are interoperable with Chinese systems, the Chinese government can conceivably create a new digital ‘sphere of influence’ through which to project power and protect its strategic interests.

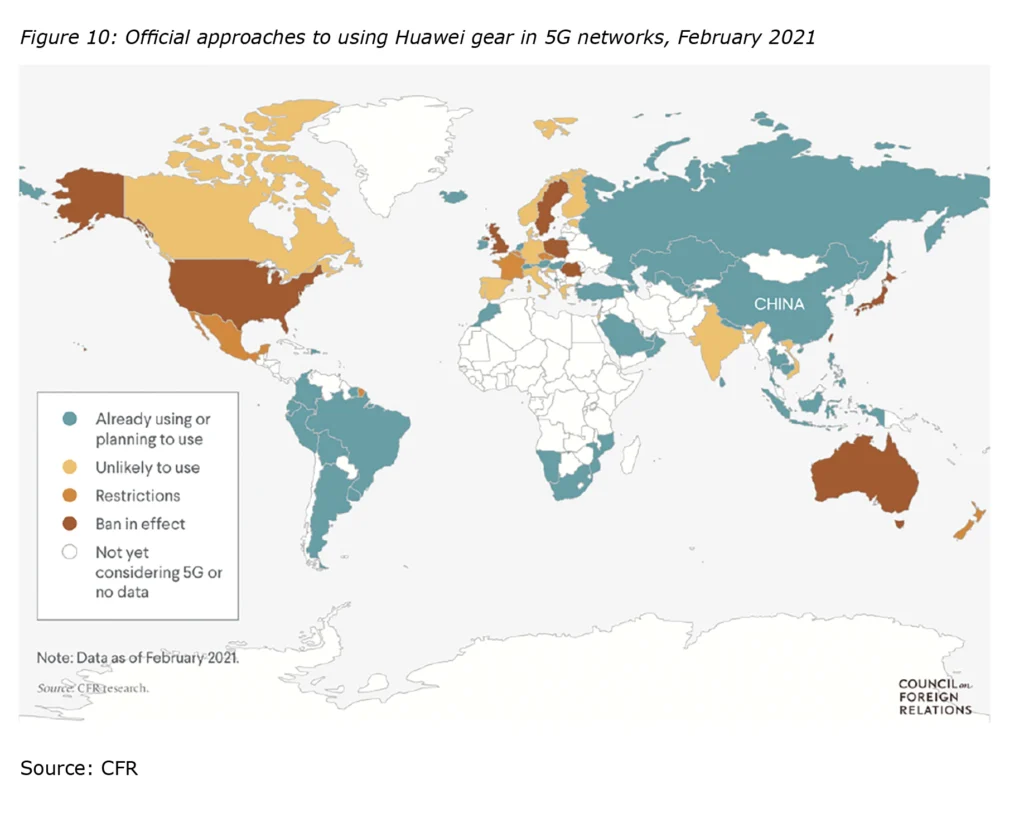

Second, states’ official or unofficial approaches to Huawei’s 5G telecommunications gear offer a model of how states will regard Chinese fintech expansion into their countries. Countries that are already using or planning to use the Chinese 5G equipment are largely in the emerging world: Latin America, Southeast Asia, Central Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. These countries will prioritise access and affordability over concerns about national security, cybersecurity, and political interference.

Third, countries that aim to stay politically ‘non-aligned’ in the race between the US and China may nevertheless accept being within China’s digital ‘sphere of influence’, consuming Chinese hardware and software, importing aspects of China’s digital surveillance and authoritarian toolkit and tech stack, and permitting Chinese investments in their local tech start-ups.

Fourth, countries with less advanced technological capabilities may opt for Chinese technologies because they offer cheaper, more efficient, and more readily available options to leapfrog into mobile-based digital payments and financial services. There are also strong commercial and trading incentives for more financially advanced countries to collaborate with the Chinese in developing central bank-to-central bank bridges or inter-bank digital payments settlement (through Cross-Border Interbank Payment System — CIPS) that would avoid US-dominated payments and settlement systems such as SWIFT and Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS). The argument for Chinese fintech has grown more compelling for some countries in light of recent financial sanctions against Russia.

But Chinese fintech, both private and state-led, will face growing pushback from more anti-China or China-skeptical countries. Chinese fintech companies are already facing growing competition from other fintech players or ‘local champions’ in Asia, for instance. Indian Reliance’s Jio Pay and Indonesian Gojek are both fashioning themselves after WeChat’s super app example—both are being funded by US tech companies. Other US tech firms, Apple, Google, and PayPal, also have strong and growing fintech presence in Asia. In addition, cultural differences between China’s neighbours have resulted in limited adoption of systems pioneered in China. For example, Singaporeans have proven reluctant to adopt mobile wallet and QR-based technologies, due to the stickiness of their card-based system.

Case-study: India

India is one notable example of the China tech backlash. India is one of Asia’s largest potential markets for digital currencies, with a highly underdeveloped retail banking and consumer credit system. Digital payments in India grew ten-fold between 2014 and 2019, a trend that we expect to continue. India had only 26.2 smartphones per 100 people as of 2018, but this number is growing fast. Indian regulators launched the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) in 2016, which facilitates bank transfers using a virtual ID. The government is also encouraging the poor to open bank accounts using their national ID numbers to receive social benefits. When regulations were lax, Chinese investors took major stakes in India’s major startup unicorns, including Paytm, Zomato, Dream11, BigBasket, Ola, and Udaan. The first major player in the Indian digital payments space was Paytm, backed by Alibaba, SoftBank, and Warren Buffett. Other major players now include Google Pay; PhonePe, backed by Walmart through its stake in Flipkart; Amazon Pay; and BHIM, developed by the National Payments Corporation of India. In 2019, Chinese investors invested close to USD 4 billion in 90 Indian startups.

However, the Indian government has now imposed new regulations requiring government approval for all Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI). It has also blocked Chinese investment in Indian start-ups. New Indian regulation has driven out Chinese tech firms and replaced them with local players. Thus, China’s early lead in India’s fintech market is being eroded by competition and regulation. Indian regulators have targeted Paytm by barring it from new customer registrations because it appears to have allowed data to be shared with China-based entities that have an indirect stake in the Indian payments company and failed to maintain adequate know-your-customer (KYC) standards.

(3) Future direction and trendlines for e-CNY

How other countries have responded to e-CNY

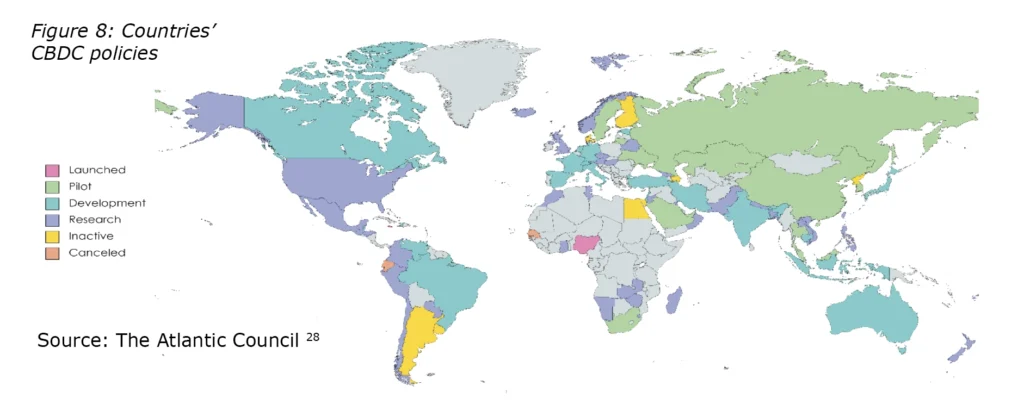

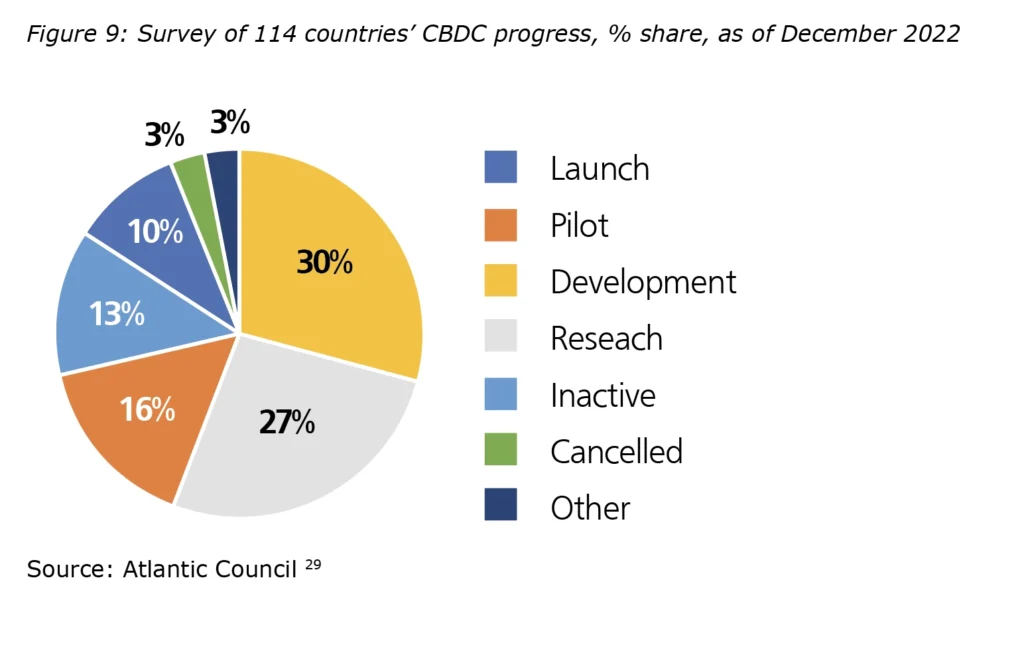

There are two major, albeit limited, challengers to e-CNY: other countries’ digital currency initiatives and cryptocurrencies. China’s e-CNY is the most advanced central bank digital currency by far, even compared with developed countries. Other countries are also experimenting with their own CBDCs. According to the Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS) 2022 report, 90 per cent of 81 central banks surveyed are conducting or about to conduct research on CBDCs, up 10 per cent from the 2020 survey.

Developed countries have yet to catch up with China in CBDC development and are broadly still in experimentation phase. While America’s card-based system is increasingly outdated, there are no concrete moves towards updating it. The Federal Reserve has avoided exploration of a digital dollar, instead focusing on its FedNow instant payments system. Movement toward a digital dollar (i.e., Project Hamilton) still requires buy-in from Congress, which has thus far been limited. The Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, the Sveriges Riksbank (Sweden), the Swiss National Bank, and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) are jointly working on technology-sharing with a focus on cross-border interoperability of digital currencies.

Beyond state-run CBDCs, there are other private digital currencies worth analysing. In Silicon Valley, Facebook shuttered its Libra stablecoin initiative, which it had hoped would facilitate cross-border payments. Cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, Ripple, Solana, and Tether also offer alternative digital currencies to fiat currencies, including central bank digital currencies like the e-CNY. While retail and institutional interest in cryptocurrencies has grown significantly since the launch of Bitcoin in 2009, these cryptocurrencies still face growing financial risks and regulatory headwinds. Cryptocurrencies will continue to grow in popularity especially in markets displaying one or more of the following characteristics: scepticism toward government institutions (e.g., Venezuela, Brazil, and Turkiye); (Philippines, Mexico, and India)….(e.g., J.P. Morgan’s JPM Coin, Santander’s Ripple system, and SWIFT gpi); strong crypto or Web3-native communities (e.g., Vietnam and South Korea); high need for cross-border remittances (e.g., Philippines, Mexico, and India). Elsewhere, fintech and Web3 companies are partnering with central banks to help build the technical side of their upgrades to the financial system.

Nevertheless, the idea that cryptocurrencies will displace government backed currencies is fanciful. Other countries’ development of CBDCs and the proliferation of cryptocurrencies globally do not necessarily hamper the internationalisation of e-CNY. Cryptocurrencies could also interact with CBDCs including e-CNY through an ecosystem of state-backed and private digital currencies. 26

On the corporate front, multinational banks in the West are making headway on real-time cross-border payments (e.g., J.P. Morgan’s JPM Coin, Santander’s Ripple system, and SWIFT gpi). Japanese banks have launched J-Coin Pay — a QR-based digital wallet designed by Mizuho Bank in association with 60 other banks in Japan.

Irrespective of the feasibility of China’s expansion of e-CNY use overseas, countries around the world are considering the implications of a more multipolar financial system in which dollar dominance begins to wane. Some countries will seek to be defensive about preserving their currency’s sway, others will try to offensively increase global use of their currencies. A third group is exploring ways to avoid the present or future threat of sanctions via SWIFT and other mechanisms, with Russia being the most recent example of this. 27

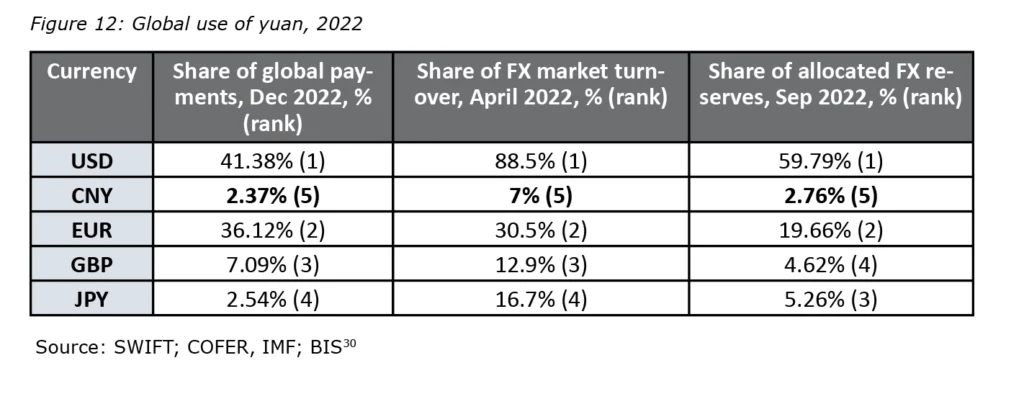

Projections of e-CNY use and impact on global FX and trade

The more effective that Chinese fintech platforms and CBDC bridges become, the more likely demand for Chinese currency (CNY) will increase. To dislodge dollar dominance, however, China must not only increase use of CNY but also enable a far larger offshore market in CNY products. Given that capital controls remain likely to be in place for the foreseeable future and given that advanced economies are unlikely to transition their trade with China to e-CNY, China will likely need to transition almost all its trade with developing and/or China-friendly countries to CBDC bridges to create sufficient offshore liquidity in e-CNY and e-CNY-linked financial products. Some amount of coercion or incentives will probably be necessary to achieve this because many economies, such as some in Southeast Asia, would be hesitant to rely on a Chinese-dominated financial system. More likely than a displacement of a dollar is a hybrid regime in which both the dollar, CNY, and other major currencies (Euros, Japanese yen, etc.) are treated as reserve currencies and must compete actively for market share.

(4) Policy recommendations

Modernise the Australian payments and settlement platforms to offer reliable rapid or instant 24/7 settlement for domestic and cross-border global transactions and an alternative competitive system to e-CNY, including:

- Enabling settlement or transfer of tokenised or digitised assets markets (e.g., for commodities, fixed income, and Australian carbon credit units)

- Considering and researching technological innovations in conditional or programmable transactions

- Enabling cheaper and faster cross-border remittances to promote financial inclusion and spur competition in the industry

Design a multi-pronged multi-stakeholder consortia approach to improving Australia’s digital payments landscape, including both public and private entities:

- Retail banks

- Fintech and tech companies and start-ups

- Governmental agencies and departments such as the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis (AUSTRAC), Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), Department of Defence and Department of the Treasury

Encourage a broader general public, private sector and legislative discussion about the viability and appeal of CBDCs (including an intelligent informed debate about available design options, opportunities and risks).

Focus on due process and privacy guarantees including effective know-your-customer and anti-money laundering provisions (KYC/AML) for law enforcement and building trust and cyber-security of technical systems .

Establish cybersecurity standards or a framework around CBDCs and/or other innovations in digital finance.

Broaden collaboration with other central banks around the world, including China’s, on best prototypes, use-cases and practices, as well as designing multiple central bank digital currency bridges with other central banks (i.e., mCBDCs and Project Dunbar).

Create regulatory clarity and a framework around fintech and digital currencies, especially around fiat-backed stablecoins so as to unlock digital value in the Australian economy in the most secure way possible.

Develop an innovation-friendly ecosystem for fintech innovations and start-ups and support public-private partnerships and consortia.

Conclusion

Beijing has both private and state-led initiatives to boost the global influence of its fintech capabilities. If China dominates the future infrastructure of international payments, it will use this as a powerful geopolitical tool. Such an outcome would insulate China from the risk of US sanctions and give China’s government a powerful lever for imposing its own sanctions. For example, China could use programmable e-CNY to force countries to use e-CNY holdings in certain ways, freeze assets, or prevent access to any individual, company, or country it wanted.

Beijing’s strategy to bolster its fintech infrastructure, however, is shifting. In the last decade, private payments systems like AliPay and WeChat Pay led the rollout of digital payments within China and seemed poised to do the same abroad. However, the international expansion of these two platforms has stalled. Beijing is now focused on two new mechanisms for boosting the influence of its fintech systems: providing technological infrastructure for fintech firms in developing countries and promoting the use of its state-backed e-CNY and the construction of ‘bridges’ between the People’s Bank of China and central banks in other countries. China’s efforts to use fintech as a tool of influence will be most successful in countries that depend heavily on Chinese economic links, as well as in less technologically advanced countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. These countries are the most likely to fall into China’s growing digital ‘sphere of influence’. Nevertheless, China’s CNY is unlikely to overtake the US dollar as the world’s predominant reserve currency, irrespective of how US-China relations develop or deteriorate.

If Australia has been alarmed by Huawei and Bytedance’s close relationship to the Chinese government, it should be just as concerned about Tencent and Alipay’s interaction with e-CNY’s centralised network, which allows the PBoC to trace all financial and payment data. Moreover, Australian policymakers should be more concerned about the capabilities of e-CNY in monitoring and manipulating financial data and access. A clear-eyed strategy in response to e-CNY would require Australian policymakers to engage in active public and political debate about the advantages and disadvantages of a digital Aussie dollar as an alternative. It would also demand an inter-departmental and public-private consortia engaged in discussing, prototyping, and designing a faster, more reliable, and cyber-secure payments and digital asset ecosystem. Finally, Australian policymakers should work actively with other central banks including China’s to explore, shape and develop best practices for enhancing the interoperability of global transactions and settlement. Failure to do so would risk Australia being left out and behind in the next era of financial digitisation and greater financial multipolarity.

Endnotes

1. While the Chinese state has certainly increased its presence in and influence over Chinese private tech companies with recent regulatory crackdowns, almost all privately owned and controlled Chinese tech firms remain strictly private. Government intervention has largely taken the form of regulatory curbs on tech platform’s monopolistic power and enforced (or encouraged) data transfers for state cyber-security purposes. See: Huang, T. and Lardy, N. (2021, October 14). Is the sky really falling for private firms. PIIE. https://www.piie.com/blogs/china-economic-watch/sky-really-falling-private-firms-china.

2. Bank of International Settlements. (2018). Central Bank Digital Currencies. https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d174.pdf.

3. Ibid.

4. Feng, C. (2022, October 13). China Digital Currency: Transactions Total 100 Billion Yuan at End of August as Uptake Marred by COVID-19 Curbs, Slowing Economy. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/tech/policy/article/3195744/china-digital-currency-transactions-total-100-billion-yuan-end-august.

5. Huld, A. (2022, September 22). China Launches Digital Yuan App—All You Need to Know,” China Briefing. https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-launches-digital-yuan-app-what-you-need-to-know/.

6. Kumar, A. (2022, March 1). A Report Card on China’s Central Bank Digital Currency: the e-CNY. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/econographics/a-report-card-on-chinas-central-bank-digital-currency-the-e-cny/.

7. China Internet Watch. (2022, April 25). China’s digital currency eCNY reached 261 million digital wallets. https://www.chinainternetwatch.com/33050/cbdc-ecny/.

8. Chinese officials could incentivize participating Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries to settle trade in digital RMB or take on digital RMB-denominated loans. While the share of digital RMB-denominated trade and lending would be raised by e-CNY, China’s lack of currency convertibility complicates efforts to raise the RMB share of global currency reserves. See: Lin, X., Xiao, Y., et al. (2017). A Research on the Belt and Road Initiatives and Strategies of RMB Internationalization. Sciedu Press, 6(1), 13-27. https://doi.org/10.5430/bmr.v6n1p13.

9. Hoover Institution. (2022, March 4). Digital Currencies: The US, China, And The World At A Crossroads. https://www.hoover.org/research/digital-currencies-us-china-and-world-crossroads. Kumar, A. (2022, March 1). A Report Card on China’s Central Bank Digital Currency: the e-CNY. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/econographics/a-report-card-on-chinas-central-bank-digital-currency-the-e-cny/. People’s Bank of China. (2021). Working Group on E-CNY Research and Development of the People’s Bank of China. http://www.pbc.gov.cn/en/3688110/3688172/4157443/4293696/2021071614584691871.pdf. Bank of International Settlements. (2018). Central Bank Digital Currencies. https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d174.pdf.

10. People’s Bank of China. (2021). Working Group on E-CNY Research and Development of the People’s Bank of China. http://www.pbc.gov.cn/en/3688110/3688172/4157443/4293696/2021071614584691871.pdf.

11. Shen, W., & Hou, L. (2021). China’s central bank digital currency and its impacts on monetary policy and payment competition: Game changer or regulatory toolkit?. Computer Law & Security Review, 41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2021.105577.

12. Chorzempa, M. (2021, January 13). China, the United States, and Central Bank Digital Currencies: How Important is it to be First? China Economic Journal, 14(1), 102-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3765709.Prasad, E. (2021). The Future of Money: How the Digital Revolution is Transforming Currencies and Finance. Harvard University Press. Xu, J. (2022, June 14). Implications of Central Bank Digital Currency: The Case of China e-CNY. Asian Economic Policy Review, 17(2), 235-250. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12396.

13. Fullerton, E. & Morgan, P. (2022). The People’s Republic of China’s Digital Yuan: Its Environment, Design, and Implications. Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI Discussion Paper No. 1306). https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/772316/adb-wp1306.pdf. Huang, Y. & Mayer, M. (2022, June 6). Digital currencies, monetary sovereignty, and U.S.-China power competition. Policy & Internet, 14(2), 324-347. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.302. Uchida, S. (2022). Comment on “Developments and Implications of Central Bank Digital Currency: The Case of China e-CNY”. Asian Economic Policy Review, 17(2), 253-254. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12381.

14. Aysan, A. F., & Kayani, F. N. (2022). China’s transition to a digital currency does it threaten dollarization?. Asia and the Global Economy, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aglobe.2021.100023.

15. Randhawa, D. (2020). China’s Central Bank Digital Currency: Implications for ASEAN. Nanyang Technology University. https://www.think-asia.org/bitstream/handle/11540/13024/PR201230_China-Central-Bank-Digital-Currency_V2.pdf?sequence=1.

16. Shu, C., He, D., and Cheng, X. (2014). One Currency, Two Markets: The Renminbi’s Growing Influence in Asia-Pacific. Bank of International Settlements. https://www.bis.org/publ/work446.pdf. Lin, See: Lin, X., Xiao, Y., et al. (2017). A Research on the Belt and Road Initiatives and Strategies of RMB Internationalization. Sciedu Press, 6(1), 13-27. https://doi.org/10.5430/bmr.v6n1p13. Matthews, J. & Selden, M.J.A. Mathews and M. Selden. (2018, November 15). China: The emergence of the Petroyuan and the challenge to US dollar hegemony. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 16(22). https://apjjf.org/-Mark-Selden–John-A–Mathews/5218/article.pdf.

17. Di Lucido, K. (2020, June 29). A Cross-Country Survey of General-Purpose Central Bank Digital Currencies. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3637684. Agur, I., Ari, A. & Dell’Ariccia, G. (2019). Designing Central Bank Digital Currencies. Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI Working Paper Series No. 1065). https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/546921/adbi-wp1065.pdf. Boar, C. and Wehrli, A. (2021). Ready, steady, go?—Results of the third BIS survey on central bank digital currency. Bank of International Settlements (BIS Papers No. 114). https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap114.pdf.

18. For a translation and analysis of the provisions, refer to Livingston, S. (2020, October 8). The Chinese Communist Party Targets the Private Sector. Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinese-communist-party-targets-private-sector.

19. For a translation of these laws refer to Sacks, S., Chen, Q., & Webster, G. (2020, July 9). Five Important Takeaways From China’s Draft Data Security Law. New America. https://www.newamerica.org/cybersecurity-initiative/digichina/blog/five-important-take-aways-chinas-draft-data-security-law/. Creemers, R., Triolo, P., & Webster, G. (2018, June 29). Translation: Cybersecurity Law of the People’s Republic of China [Effective June 1, 2017]. New America. https://www.newamerica.org/cybersecurity-initiative/digichina/blog/translation-cybersecurity-law-peoples-republic-china/.

20. Sacks, D. (2021, March 29). China’s Huawei Is Winning the 5G Race. Here’s What the United States Should Do To Respond. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/blog/china-huawei-5g.

21. MOFCOM. (2022). 2021 Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment. China Commerce and Trade Press. http://images.mofcom.gov.cn/fec/202211/20221107152537194.

22. Ibid.

23. Richter, F. (2019, August 29). Infographic: The Tourists Splashing the Most Cash. Statista. https://www.statista.com/chart/15588/international-tourism-expenditure-in-2017/.

24. Ant Group. (2020). Ant Group H Share IPO Prospectus. https://www1.hkexnews.hk/listedco/listconews/sehk/2020/1026/2020102600165.pdf.

25. Sun, Z. (2021, August 20).[The emergence of two primary e-CNY access channels for small and medium-sized banks]. Shanghai Securities News. http://paper.cnstock.com/html/2021-08/20/content_1509724.htm

26. Carney, M. (2021, June 28). The Art of Central Banking in a Centrifugal World [Transcript]. https://www.bis.org/events/acrockett_2021_speech.pdf.

27. Xu, K. (2022, March 7). Central Bank Digital Currency: Should You Want It Too. Interconnected. https://interconnected.blog/central-bank-digital-currency-should-you-want-it-too/.

28. Kumar, A. (2022, March 1). A Report Card on China’s Central Bank Digital Currency: the e-CNY. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/econographics/a-report-card-on-chinas-central-bank-digital-currency-the-e-cny/.

29. Ibid.

30. SWIFT. (2022). RMB Tracker document centre. https://www.swift.com/our-solutions/compliance-and-shared-services/business-intelligence/renminbi/rmb-tracker/rmb-tracker-document-centre. IMF. (2022, December 23). Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER). https://data.imf.org/?sk=E6A5F467-C14B-4AA8-9F6D-5A09EC4E62A4. BIS. (2022, October 27). OTC foreign exchange turnover in April 2022. BIS Triennial Central Bank Survey 2022. https://www.bis.org/statistics/rpfx22_fx.pdf.

Image courtesy of Jeff Nishinaka Paper Sculpture