This paper proposes a non-disruptive education reform to expand the number of university places at no further cost to taxpayers.

Expand University Places without Blowing Out Budgets: Executive summary

As Australia heads to the polls in 2022, higher education is, as usual, a question with only one answer: more money. The Coalition has promised $2.2 billion for research commercialisation. Labor has countered with $1.2 billion of additional Commonwealth funding for higher education, including 20,000 new university places. If Labor wins, Australian taxpayers will probably end up funding both sets of promises. And that, at a time of massive spending deficits and a national debt forecast to hit 50% of GDP in 2025.

Spending on this scale might be reasonable, if Australian higher education were severely underfunded and in need of a top-up. But Australia’s per-student public spending on higher education is already the eighth-highest among member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development — and as a proportion of GDP, it’s higher than in the United Kingdom and the European Union. Australia’s universities already received a $1 billion research top-up during the coronavirus pandemic, in addition to expanded funding for domestic student places. It’s hard to see how they could possibly need more money.

There is always political pressure to expand education opportunities, particularly by making it possible for aspiring students to obtain university degrees. Although some critics of the current focus on university-level education would prefer to see a greater emphasis on TAFE-level vocational qualifications, the reality is that young people (and their parents) have a strong preference for university education. Expanding opportunities necessarily means reducing university admissions standards, which may or may not be good social policy. Whether or not the number of university places should be expanded is debatable, but if the number of places is to be increased, it is important to do so in a cost-effective manner.

It might seem obvious that the only way to expand opportunity is to increase student numbers: either the taxpayer must pay for more places, or the universities must cram more students into already-crowded classes. In reality, there is a third way. Australia could immediately expand opportunities for university education at zero cost to the taxpayer simply by limiting Commonwealth support to one degree per course and one course per student. This ‘1/1 policy’ would fund more students in university places to obtain one undergraduate degree instead of paying for fewer students to obtain multiple undergraduate degrees.

Australia’s current university funding arrangements for university places encourage universities to keep students enrolled in Commonwealth Supported Places at the undergraduate level as long as possible: three-year degrees are expanded into four-year degrees; universities package two or even three degrees into a single bachelor’s course; students who want to switch fields are incentivised to undertake a second bachelor degree course instead of progressing to the master level. The result is that instead of educating more students, Australia’s universities use the limited pool of Commonwealth funding to offer more degrees — to the same students.

The 1/1 policy would flip this logic, spreading a limited number of undergraduate places among more students. Unfortunately, the Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE) does not publish sufficiently detailed data to support a calculation of the exact number of additional places that would be created. Indicative calculations based on the data that are available in the public domain suggest that the 1/1 policy could open up as many as 80,000 new Commonwealth Supported Places at no additional cost to the taxpayer. Even allowing for a possible overestimation by a factor of two, this still represents double the number of new places promised by the Labor Party for 2023-2024.

The 1/1 policy would also incentivise students to engage in educationally-appropriate behaviours, progressing from lower- to higher-level degrees instead of sitting through a succession of introductory classes. Appropriate progression is at the heart of the ‘Melbourne Model’, introduced at the University of Melbourne in 2008 and copied at the University of Western Australia between 2012 and 2020. The Melbourne Model puts undergraduate education in line with the Bologna Process model for the creation of a standardised European Higher Education Area. It also accords with general higher education practices in the United States.

The current structure of Commonwealth funding incentivises universities to retain top students in introductory-level bachelor degree programs instead of progressing them on toward more advanced study. As of 2022, students are limited to seven years of Commonwealth support, but this is far too long. It leads to students pursuing as many as three bachelor degrees in a single course of study. A 1/1 policy would make more administrative, financial, and pedagogical sense. It is a non-disruptive education reform that would promote the more efficient use of public resources while improving educational outcomes.

Australia’s Byzantine undergraduate landscape

Pity the well-performing Australian school student. High school is hard enough without having to wade through the myriad marketing pitches delivered by Australia’s 38 publicly-supported universities. Australia’s prospective university students face the bewildering prospect of choosing from among no fewer than 5099 distinct undergraduate courses, counting equivalent courses at different institutions separately. Aggregating course titles across institutions still leaves prospective students with at least 3417 different courses to choose from, each of them leading to one, two, or (in some cases) three undergraduate degrees. The most extravagant of these, Sydney’s triple-degree courses in medicine, surgery, and the student’s choice of commerce, music, or science, take seven years. Wollongong’s Bachelor of Engineering (Honours)-Bachelor of Laws also takes seven years, and many other universities have combined bachelor degrees that take five or more years to complete.

Outside the vapid logic of marketing, there seems little reason to retain students in undergraduate study for five, six, or even seven years. Universities, however, benefit from bundling multiple undergraduate degrees into combined courses because it helps them keep students enrolled for longer periods in Commonwealth Supported Places. It also allows them to keep high-performing students enrolled for longer periods of time, increasing the proportion of high-performing students in their overall student bodies. This educationally and financially profligate practice is made possible by the government’s decision not to place limits on the number of undergraduate degrees a student can take with government support (although, as of 2022, there is a limit of seven total years of support). Universities are, in effect, incentivised to hold onto good students for as long as they can, even though it would make more pedagogical sense to encourage students to progress from undergraduate to postgraduate study.

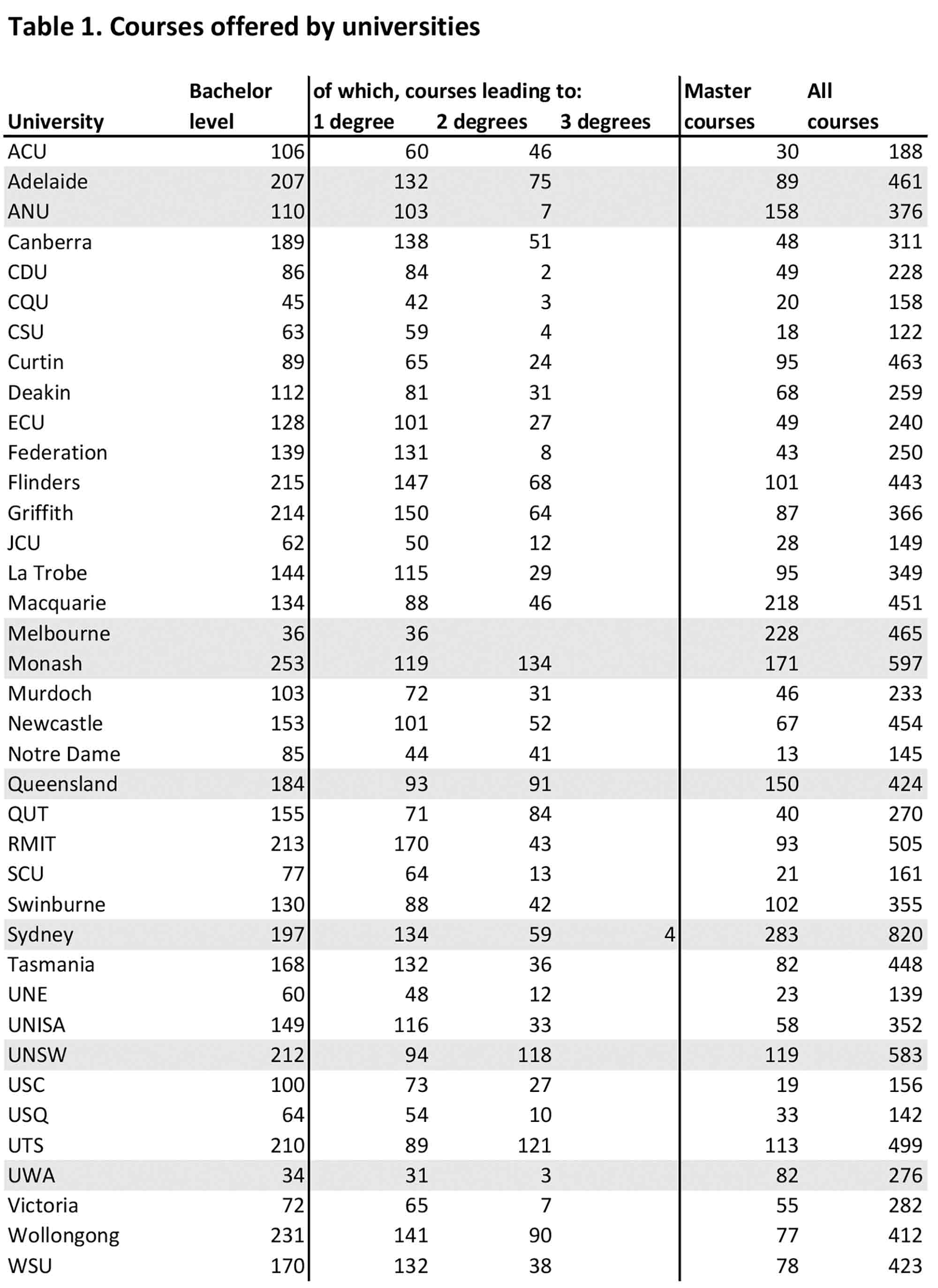

The exact number of undergraduate degree courses being offered in Australia is unknown, both because it is always changing and because course data for self-accrediting institutions (like public universities) are not published by the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA). Data are, however, available for courses that are registered with DESE to be offered onshore to international students. This Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Courses for Overseas Students (CRICOS) exists to serve as the basis for the issuing of student visas, but it can also serve as a proxy for the courses available to domestic students as well. Based on CRICOS registrations, the number of bachelor and master degree courses offered by each of Australia’s 38 publicly-funded universities is given in Table 1. These data exclude the 1510 stand-alone honours degree courses, which are one-year mini-courses that can be tacked onto a bachelor’s degree in order to obtain an ‘Honours’ award. The data do, however, include courses that incorporate embedded honours degrees, like the four-year BA(Hons) or BS(Hons) degree courses.

Two universities stand out for the relatively small number of bachelor degree courses they offer: Melbourne (23) and UWA (28). By contrast, 16 universities offer 100 or more bachelor degree courses — and that’s not counting master degree courses, of which there nearly as many (3149) as bachelor degrees. The University of Sydney takes the prize for the largest number of CRICOS-registered courses, with 820 courses of all kinds, giving an average of 84 students per course. The average Australian university offers 134 different undergraduate degree courses, making the comparison of courses across universities all but impossible.

It would be disingenuous to make too much of this proliferation of courses; to a large extent, it simply reflects the fact that most Australian universities follow the British model of defining courses narrowly instead of the global (American, European, and Chinese) model of defining causes broadly. The British model tends to lock young scholars into highly structured courses at a time in their lives when they may not fully understand what those courses even are, what careers they might lead to, and indeed what careers they themselves might want to pursue in life. The global model, by contrast, is more flexible, allowing students to change majors within courses until relatively late in their undergraduate careers. The global model may produce fewer regrets than the British model, but it does so at the price that undergraduates often end up with generalist first degrees, and require further postgraduate coursework before starting their adult careers.

The global model was adopted at Melbourne in 2008 with an attempt to consolidate all its bachelor degrees into six courses, and thus it came to be known in Australia as the ‘Melbourne Model’. This pioneering effort was followed by a 2012 transition at UWA from 62 bachelor degree courses to just five. Melbourne never quite got down to six degree courses, but it came close, and has only crept up since due to a fracturing of its studio arts offerings into multiple specialisations. The University of Western Australia did make it down to five bachelor degree courses, and held that line until 2020, when a new vice-chancellor quietly threw in the towel. Despite traditionalist resistance, the Melbourne Model offers a positive vision for the future of undergraduate education in Australia. But as the experiences of both Melbourne and (especially) UWA demonstrate, that vision is stillborn.

At UWA, the initial suite of five undergraduate degrees really consisted of four degrees (Arts, Commerce, Design, and Science) plus a high-ATAR elite degree with embedded honours labeled the ‘Bachelor of Philosophy’ that allowed students to pursue a major in any of the four basic degrees. This lasted until 2018, when a high-ATAR Bachelor of Biomedical Science was carved out of the ordinary Bachelor of Science, with the Bachelor of Design being retired to compensate. But the dam was broken, and in 2021 UWA introduced six new courses and a slew of combined courses. The university will offer another 13 new bachelor courses in 2022. In its 2020 annual report, UWA offered a terse two-word explanation for the abandonment of its eight-year experiment with the Melbourne Model: ‘increased competition’. These educationally-appropriate degrees were failing in the market — in a market structured by the Commonwealth in a way that rewards complexity and obfuscation over simplicity and direct competition.

A well-functioning market for undergraduate degrees

In a well-regulated market for undergraduate degree courses, universities would compete to attract the best students by offering desirable student experiences that lead to successful student outcomes. Universities would offer a limited number of standardised degree courses, on which systematic data could be collected and league tables compiled. Relevant metrics might include average class sizes, international student enrolments, student satisfaction levels, graduation rates, graduate employment outcomes, and graduate salaries — all reported at the course level. Reinforced by anecdotal feedback from current students and graduates, these data would give prospective students the tools they need to make well-informed decisions about their university studies.

But in Australia’s almost unregulated market for undergraduate courses, the pressure of competition has been shifted from course differentiation to admissions segmentation based on target Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR) levels. Innovation focuses on designing attractive-sounding degree labels that can be attached to stratified ATAR ‘price’ points. Star students are encouraged to pursue elite high-ATAR degrees, instead of ‘wasting’ their ATARs on degrees with low minimum entry cutoffs. This might make sense, if these stratified degrees segmented students into distinct disciplinary cohorts; for example, medicine versus nursing. Instead, ATAR competition, reinforced by competition for international student enrolments, has created a system in which degrees are proliferated purely for admissions marketing purposes. Students in these bespoke degrees sit side by side in the same classrooms, learning the same material, despite undertaking notionally distinct programs of study.

At the University of Sydney, for example, a student can complete a major in psychology leading to an honours year and eventual professional accreditation through any one of 18 different undergraduate courses, including the Bachelor of Liberal Arts and Sciences (with a ATAR guide rank of 70), the Bachelor of Arts (80), the Bachelor of Science (80), the Bachelor of Science and Bachelor of Advanced Studies – Advanced (90), the Bachelor of Psychology (95), and the Bachelor of Science and Bachelor of Advanced Studies – Dalyell Scholars (98). With minor exceptions, students in all of these courses will take the same 10 units of study that constitute the psychology major. The 18 different courses allow students to do different things alongside their psychology majors, and can be defended as catering to student interests. But if they existed primarily to cater to student interests, why not assign them the same minimum ATAR? It is hard to escape the conclusion that the primary purpose of these ornate course offerings is to segment the student market by ATAR.

A more student-centred, market-driven approach to structuring undergraduate courses would limit universities to offering a finite number of single-degree courses while limiting students to one lifetime undergraduate degree course on a Commonwealth-supported place. This ‘1/1 policy’ would mandate a system-wide model of one degree per course and one course per student, increasing university places. Universities should further be required to structure each of their undergraduate degree courses to fit under one of a dozen or so standard labels (e.g., Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science, Bachelor of Engineering, etc.) approved for funding by the government. Annual student satisfaction and employment outcome surveys like those currently undertaken by the Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT) program could then report outcomes by degree for each university offering that degree course. This would allow students, parents, and regulators to compare degree outcomes across universities.

Under such a system, students would have the information they need to make informed decisions about their futures — and about the universities competing to attract their government-subsidised dollars. Universities, unable to compete on degree branding (since degree names would be standardised) or on price (for Commonwealth-supported places), would be forced to compete on outcomes. The Commonwealth would benefit from reduced costs, as students progressed logically from highly subsidised undergraduate study to less-subsidised postgraduate study. Alternatively, existing Commonwealth funding could be used to make undergraduate degree courses available for more students, instead of concentrating funds on a smaller number of students wastefully pursuing multiple degrees. With an expected increase in the number of domestic students needing university places in the 2020s, it would make a lot of sense to provide more students with one bachelor degree than fewer students with multiple degrees.

The 1/1 policy would support the creation of a higher education market microstructure that rewards educational performance instead of marketing prowess. A market microstructure defines the rules by which a market operates. For example, on the Australian Stock Exchange, stock options generally represent contracts for 100 shares, for delivery on the third Thursday of the month, at a series of predefined strike prices. This microstructure leaves only the value of the options contracts to be determined by market forces and ensures that options are valued transparently and efficiently. Contrast this with the market microstructure for mobile phone data plans. The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission allows mobile data providers wide latitude in setting contract terms, with the result that consumers are generally unable to directly compare the plans offered by different providers. Consumers are offered a variety of contract terms, but price discovery in the market as a whole is opaque and inefficient. It is very difficult for consumers to determine which providers offer the best plans.

Efficiency and transparency are not the only goals of market microstructure, and sometimes other priorities rightly predominate. Many might argue that universities should be free to innovate by offering bespoke degree courses tailored to meet individual student needs. Yet although the highest-performing American universities are extraordinarily free to innovate, they have arrived — subject to many minor fiddles — at a standard four year undergraduate degree course. European countries have also arrived at a standard four-year undergraduate degree followed by progression to postgraduate study, though they have done so through consultation and planning. The key difference between these models and Australian university markets isn’t the microstructure; it’s the macrostructure.

In the United States, most students pay for their courses, either directly or via hard loans with fixed interest rates. After a two-decade review process that began in 1999 (the ‘Bologna Process’) European governments also endorsed a standardised four-year undergraduate course structure for the European Higher Education Area, which covers nearly all of Europe, Turkey, and the former Soviet countries. These global higher education market macrostructures discipline universities to serve students, who can directly compare the courses being offered by competing universities. The Australian macrostructure encourages universities to serve themselves. They are free to design courses that suit university priorities, instead of being subjected to market discipline within the framework of a fixed course structure.

Undergraduate degree courses in Australia aren’t bought by students. They’re bought by the government, which then offers them to students on a concessional basis. Under these conditions, students cannot realistically be expected to subject universities to market discipline. Notwithstanding the market-friendly rhetoric of the Job-Ready Graduates Package, the price signals provided to students are so distorted by Commonwealth contributions, HELP loans, and broad government infrastructural support for university research and facilities as to be almost meaningless. In any case, Australian universities do not compete on price for domestic students. In theory, they compete on quality, but like mobile data providers, they have evolved a market microstructure so arcane that it makes direct quality comparisons between universities (or even between courses at the same university) next to impossible.

The Commonwealth, as the effective paying customer for most domestic undergraduate courses, should step in to reform the market microstructure for Australian university degrees, to increase university places. Assuming that the government will maintain its established practice of setting fixed prices for university courses, it should use its purchasing power to shape a standardised menu of degree courses that are eligible for Commonwealth support. To reduce costs and expand educational opportunities, the menu should be structured on the 1/1 policy. There is little rationale for the Commonwealth to fund multiple combined bachelor degrees in a single course (as it does now) instead of encouraging students to move on from their first bachelor degrees to master-level study. Taking the Melbourne Model as a guide, a limited number of no more than a dozen bachelor degrees should be approved for Commonwealth support, subject to revision on a five or (better) ten year cycle. And to help students compare the quality of degrees across universities, the DESE should make its QILT survey results available in a more accessible format, publishing degree-level scores alongside other relevant metrics like minimum ATARs, offer acceptance rates, average class sizes, and percent international students.

Scoping out the 1/1 policy to expand university places

Only the DESE has the detailed data on undergraduate enrolments that are necessary for calculating the exact scale of the expansion in educational opportunities that would be enabled by the 1/1 policy to expand university places. It is possible to estimate the scale of the expansion, however, using data that are publicly available for the University of Queensland. As a highly-ranked metropolitan university that is a member of the Group of Eight (Go8) research-intensive university lobby group, UQ is not necessarily typical of the rest of the Australian university system, but it is not clear that any other university publishes the data required for scoping out the 1/1 policy. Even UQ does not make the requisite data readily accessible to the public, but to the university’s credit, they can be accessed via a guest login to the university’s ‘UQ Reportal’ corporate data website. The UQ data are thus used here as indicative of the gains that could be achieved through a national 1/1 policy.

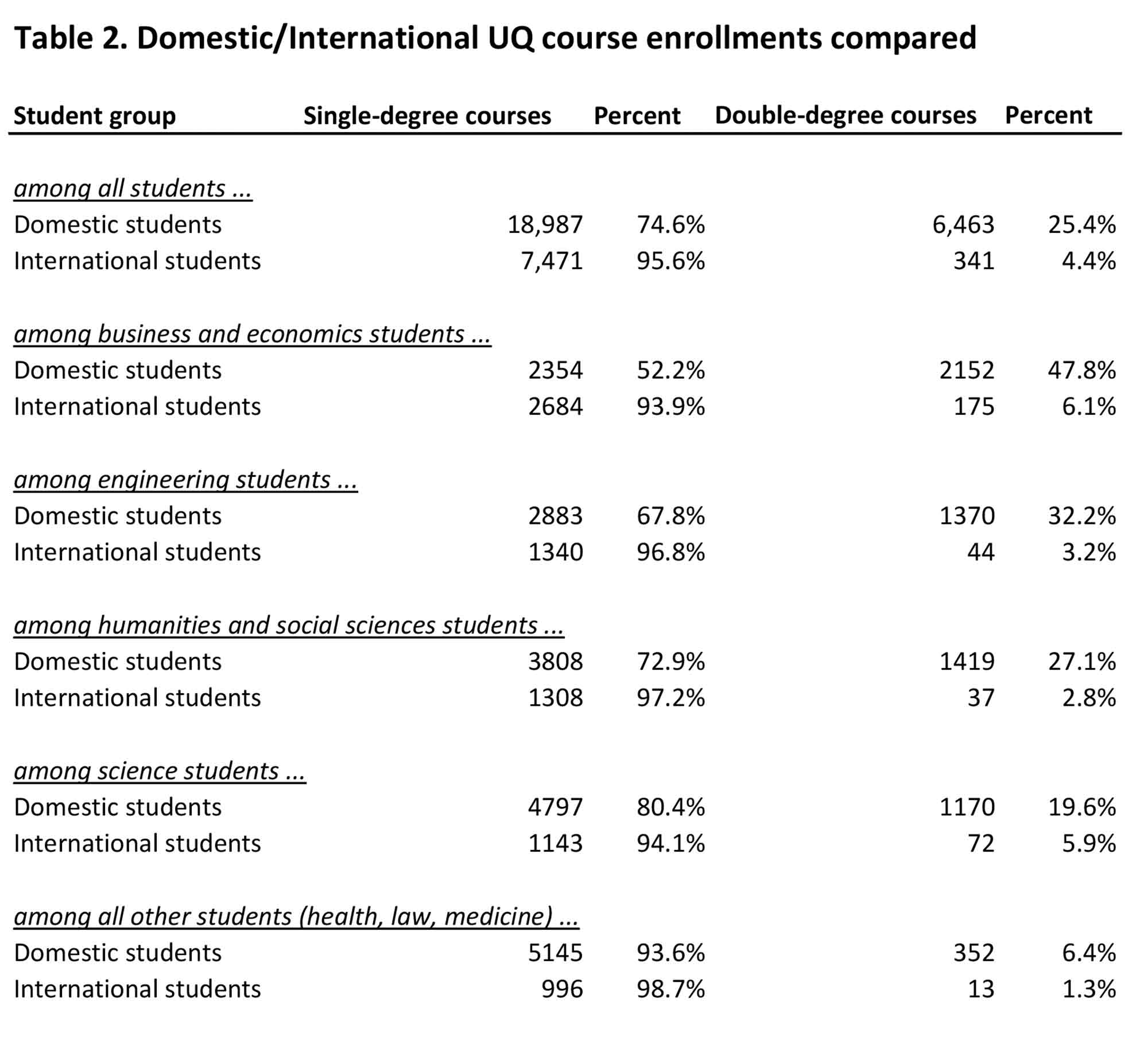

Table 2 reports UQ enrolments by single-versus-double degree courses for domestic students. The equivalent figures for international students are reported for comparison. As shown in the top panel of the table, slightly more than a quarter of all domestic undergraduates at UQ are enrolled in courses that result in not one, but two, degrees (UQ does not offer triple-degree courses). The most popular of these double-degree courses is the Bachelor of Arts / Bachelor of Education (Secondary), with 588 domestic students and 21 international, which is a 208-week (year) course. The second most popular is the Bachelor of Arts / Bachelor of Laws (Honours) with 462 domestic and 4 international, a 286-week (5.5-year) course. The standard UQ Bachelor of Arts, by contrast, is a 156-week (3-year) course. That course enrols 2,296 domestic students and 851 international. It seems that international students, who must pay up front for their degrees, do not perceive the same advantages in extended study at bachelor level.

That said, it is clear that these two popular double-degree courses are not typical of the kinds of courses that international students might pursue. In any case, secondary education might more appropriately be restructured as a four-year single-degree course requiring a substantive specialisation in the area to be taught. By contrast, nearly all domestic law students at UQ opt for double-degree courses combining law with a second degree. Arguably, these elite students (minimum ATAR 98) should either be studying law as a postgraduate subject, or putting their legal educations to good use after four years of study, instead of continuing at university for another one and a half or two years to pick up a second, less-competitive, less-prestigious tack-on degree. It is quite likely (although the data are not available to substantiate this suggestion) that many of those law double-degree students never intend to practise law at all, but are merely studying law so as not to ‘waste’ their high ATAR scores. The existing structure of Commonwealth funding actually encourages this kind of behaviour.

In order to make more meaningful comparisons between domestic and international student choices, the lower panels of Table 2 break out single and double-degree course choices by broad field of study. Nearly half of all domestic business and economics students at UQ choose to pursue a second degree, compared to only 6.1% of international students. This is the most extreme disparity, yet it represents the greatest proportion of international double-degree students in any field. Although double degrees offer international students the opportunity to spend extra time living and gaining work experience in Australia, they apparently do not recognise value for money in doing so. Most likely, they correctly perceive that a single undergraduate degree followed up by further specialisation at the master’s level is a more efficient use of their time and money than persisting in bachelor’s level study beyond the minimum time necessary.

Taking the UQ figure — that roughly a quarter of domestic students opt for multiple-degree courses — as a proxy that can be applied to the sector as a whole, it is possible to very roughly estimate the number of new Commonwealth Supported Places that might be opened up under the 1/1 policy. First, it must be recognised that some of the existing double-degree courses would reasonably be converted into 4-year single-degree courses under the 1/1 policy. Thus a more conservative indicative figure for the proportion of domestic students who are enrolled in double-degree courses that are educationally inappropriate might be 20%. The TEQSA data underlying Table 1 indicate that multiple-degree courses take, on average, 56% longer to complete than single-degree courses. Conservatively reducing that to 50% extra time, and assuming that 20% of future students would switch from multiple-degree to single-degree courses, a reasonable guess is that current Commonwealth funding could stretch to accommodate 10% more students under the 1/1 policy.

There are currently around 850,000 students in Commonwealth Supported Places. Roughly half of these students are studying part-time, and it is unknown (to the public) how many of those are in single- versus multiple-degree courses. Assuming that full-time students are slightly more likely than part-time students to enrol in multiple-degree courses, the final number of new places opened up by the 1/1 policy might be estimated at 80,000. It is possible, however, that UQ enrols an exceptionally large number of multiple-degree students. Even if these estimates overstate the number of new places by a factor of two, the number of new places that would be freed up by the 1/1 policy would still be 40,000, or double the ambition of the Labor Party’s 2022 election manifesto.

Alternatives to the 1/1 policy

The current funding model for undergraduate education in Australia encourages universities to steer top students toward multiple-degree programs at the undergraduate level. Multi-year funding is agreed annually between DESE and each university, with funding for general courses (i.e., other than medical or other special priority courses) allocated as a lump sum via a ‘basic grant’. The universities themselves have the autonomy to choose which students to support for what degree courses, subject to very broad limits. The student must be an Australian citizen, an Australian permanent resident, or a New Zealand citizen who will reside in Australia. Each student can be funded for a maximum of 7 years of full-time study. The 7 year maximum was only introduced in 2022; units of study taken in earlier years do not count toward the limit.

Universities that want to maximise the overall quality of their student bodies are thus currently incentivised to retain top students in multiple degree courses that can take up to 7 years to complete. Attracting students into multiple degree courses also has the potential to reduce universities’ overall recruitment costs. The biggest reason to offer multiple degree courses, however, may be that they are popular with students. No systematic data are available on this, but it is easy to imagine an enthusiastic teenager eagerly plotting the completion of multiple degrees, like UQ’s popular combined arts and combined law degrees.

Within the context of the existing funding model, increasing university places means increasing Commonwealth funding. It might also require increased capital expenditure, if universities have to expand facilities to accommodate increased student loads. This is, obviously, the universities’ preferred outcome. As with the 1/1 policy, increasing the number of places within the current funding structure would imply a reduction in admission standards as universities dip deeper into the pool of aspiring students. Both the 1/1 policy and an increase in places within the existing structure would lead to higher levels of student dropout (course non-completion) at the margin, as less-qualified students who previously were excluded from university education are admitted to university-level study.

Compared to the existing model, the 1/1 policy could lead to higher levels of (concessional) student debt, and thus potentially to higher levels of Commonwealth lending and concomitant default risk. The 1/1 policy would encourage high-performing students to progress from undergraduate to postgraduate coursework study instead of pursuing multiple degrees at the undergraduate level. Postgraduate coursework study is primarily funded via concessional (interest-free) FEE-HELP loans that are repayable through the tax system. The potential additional liability to the Commonwealth created by increased FEE-HELP support would be balanced by the likelihood that the 1/1 policy would disproportionately push the best students toward postgraduate study. Holding the number of postgraduate places constant, the mix of FEE-HELP liabilities would actually improve. Allowing postgraduate places to expand in response to demand would likely lead to only a small increase in Commonwealth outlays.

Many prominent higher education analysts believe that, instead of expanding the number of students in university courses, Australia should encourage some less-qualified students to pursue vocational education instead. A detailed analysis from the Grattan Institute, however, concludes that: “For some lower-ATAR men, a few courses would probably increase their employability and income. But for lower-ATAR women, higher education is almost always their best option” That is at best an equivocal endorsement of the vocational route for only a small subset of aspiring students. Another way of stating this conclusion is that university education is a better option for everyone except a subset of men with low ATAR scores. The primary alternative route suggested for men is for them to preference vocational business education over university humanities education.

An expansion of university business places by opening them to lower-ATAR students might accomplish the same goal. It seems likely that the relatively high ATAR cutoffs for many business degree courses reflects high demand, not a hard intellectual limit for the study of business. If this is the case, then universities could expand opportunities for business study by reducing minimum ATAR cutoffs to the levels that prevail for arts, nursing, and teaching. Of course, universities disproportionately allocate their available business education places to international students. At the University of Queensland, international students take up more than a third of the available undergraduate business places (see Table 2). Under the 1/1 policy, universities might be encouraged to meet domestic student demand instead.

Conclusion

University reform is perpetually on the agenda. When the education minister mentioned the possibility of university specialisation in a June 2021 speech, commentators immediately took it as an invitation to lobby for greater differentiation between research and teaching intensive universities. It’s not at all clear that’s what the minister meant by opening a conversation on “greater differentiation and specialisation in the university sector”, but it was what (certain) universities wanted to hear. Differentiation and specialisation might simply mean that some universities host law schools while others host medical schools, instead of a separation by research intensity (and thus, inevitably, prestige). It might mean that the Commonwealth would offer to fund a menu of a dozen or so undergraduate degrees, and each university would specialize in offering a subset of degrees chosen off that fixed menu.

The standardisation of Commonwealth supported university places on the basis of one degree per course / one course per student (the 1/1 policy) would immediately free up tens of thousands of new university places at no extra cost to the taxpayer. Over time, it would also give the government the data it needs to increase efficiency and drive down costs. For example, the government could shift Commonwealth supported places from high-cost providers to low-cost providers by creating an auction-style market for degrees. Since the basic parameters of degree courses would be fixed across universities, the government could offer more places in any particular degree course to those universities that were willing to teach the course at a lower price point. Through this mechanism, the Commonwealth could use its purchasing power to drive forward the “greater differentiation and specialisation in the university sector” mentioned by the minister by gradually shifting student load in particular subjects to the universities that prove themselves most able to teach them efficiently.

If combined with broader reforms to the regulation of university degree courses, the 1/1 policy to expand university places could also lead to the production of much better statistical tools for evaluating educational outcomes across universities and degree courses. Currently, the complexity of Australia’s university landscape — with the average university offering 134 different undergraduate degree courses, with a total of more than 5000 distinct courses being offered across the entire public university system — makes it practically impossible for students, parents, and even government ministers to compare the relative performance of different universities. The 1/1 policy, combined with reforms to limit Commonwealth Supported Places to a fixed menu of degree options, would support the production of meaningful performance metrics on which universities and their degree programs could be evaluated.

The 1/1 policy is simple, straightforward, educationally appropriate, consistent with international norms, and easy to implement. Current students should of course be allowed to complete their in-progress degree courses under the funding rules that applied when they first enrolled. But new cohorts should be funded under the 1/1 policy to expand university places. This would likely free up a cumulative 20,000 Commonwealth Supported Places per year for the first three or four years, eventually expanding access to undergraduate degree courses by as much as 80,000 students per year. The DESE has all the relevant data with which to make the necessary calculations for presenting a fully-developed plan to the education minister. Either party could implement the 1/1 policy after the election while staying true to its core political principles. All that is required to make it happen is the political will — the political will, that is, to take on the universities, in the interest of students, parents, and taxpayers.

FURTHER READING:

Endnotes

Angus Taylor, 2022, ‘Action Plan to Supercharge Research Commercialisation’, Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources, February 2.

Stephanie Dalzell, 2021, ‘Labor Gets Election-Ready with $1.2 Billion Promise Including Free TAFE and More University Places’, ABC News, December 4.

Rob Dossor, undated, ‘Commonwealth Debt: Budget Review 2021-22 Index, Parliament of Australia.

Salvatore Babones, 2021, Australia’s Universities: Can They Reform?, Ocean Reeve Publishing, page 34.

Unsigned, 2021, ‘Annual Report 2020’, University of Western Australia, page 18.

Hazel Ferguson, 2021, ‘A Guide to Australian Government Funding for Higher Education Learning and Teaching’, Parliament of Australia, April 23.

Andrew Norton, 2019, ‘Rewards of VET Need to Be Better Known’, The Australian, August 14.

Andrew Norton and Ittima Cherastidtham, 2019, ‘Risks and Rewards: When Is Vocational Education a Good Alternative to Higher Education?, Grattan Institute, page 52.

Ibid., pages 35-37.

Stephen Parker, Keith Houghton, and Mark Clisby, 2021, ‘Why Alan Tudge is right to talk about specialisation in universities’, The Australian, June 8.

Alan Tudge, 2021, ‘Our priorities for strengthening Australia’s universities’, DESE, June 3.