Introduction

The Education Goals for Young Australians prioritise “excellence and equity” and the formation of “active and informed members of the community”. However, Australian students’ well-documented decline in academic achievement (especially in the English language) has eroded public confidence. Furthermore, their inadequate understanding of the nation’s governance has led to a 2024 Senate Inquiry into civics education, engagement, and participation in Australia.

The latest wave of Australian education reform now centres on restoring evidence-based approaches to what and how students learn. Borrowing heavily from traditional practices, and drawing on what is commonly referred to as ‘the science of learning’,[1] this involves creating a “knowledge-rich curriculum” with “coherent and sequenced” content, supported by “explicit” teaching.[2]

The so-called 21st century skills (the 4 Cs) of communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity[3] seem naturally aligned with the traditional practice of debating. Working either solo or as part of a team, an effective debater undertakes sound research, anticipates and responds to all possible perspectives, takes a reasoned position, and makes the case articulately and persuasively.

While the Australian Curriculum advocates the development of argumentation skills — mainly through writing — the few references to the art of debating do not reflect the evidence of its significant cognitive, linguistic, philosophical and socio-political benefits. Thus, schools and teachers are less likely to include it among their strategies for meeting curriculum requirements.

Evolving over millennia from its ancient Greek origins, debate is at the heart of Western intellectual culture. Described as “a well-known pedagogical technique since there have been written records about teaching and learning”, it is a proven instrument for sustaining Western traditions that prize logic, linguistic dexterity and the robust, civil exchange of ideas.[4] In the 21st century, debating takes many forms, from a highly structured parliamentary style to team policy, one-on-one and public forum debates. Technology allows considerable innovation. Much of the resilience of this ancient art, according to researchers, is due to “its associations with two powerful concepts: critical thinking and democracy.”[5]

The available research underscores its potential to address academic and cultural deficits in the education of young Australians. It is a proven strategy for cementing knowledge across multiple subject areas, enhancing English language proficiency and for encouraging thoughtful, articulate, confident civic engagement.

A second review of the Australian Curriculum (2021-2022)[6] missed a crucial opportunity to prioritise citizenship and nation-building, in which debate plays a key role. In the absence of a rigorous academic framework, Australia’s national curriculum lacks deep and unifying philosophical and intellectual themes. By contrast, the world’s highest-performing education system — where English is the language of instruction — places a meticulous emphasis on citizenship. Singapore’s national curriculum is grounded in national values.

At the time of writing, the 48th Parliament of Australia is due to be elected by May 2025. An election magnifies the challenges for politicians as they seek to defend their legislative positions. It also highlights an undervalued and arguably underused obligation of Australia’s political leaders: the debate.

Federal and state/territory governments are under intense public scrutiny regarding cost-of-living pressures, energy supply, national security and defence, immigration, productivity, indigenous representation, health, education, youth crime and numerous other policy areas. Calls for open and comprehensive debate on these issues are a reminder of an ancient practice that stimulates civic participation, holds political leaders to account, and remains a cornerstone of a free and civil society. The lead-up to an election is also a timely opportunity to consider the effectiveness of the two Education Goals for Young Australians authorised by the nation’s nine education ministers.

This paper places the ancient art of debate at the nexus of an impending election, rising scepticism about political leadership and decision-making, and ongoing concerns about the effectiveness of national education goals in preparing young Australians for post-school life and work in a democracy. A renewed emphasis on debating across the curriculum would raise the academic bar (especially in the English language), boost students’ appreciation of Australia’s Western foundations, and strengthen the nation’s democratic decision-making culture.

Debating takes many forms in school contexts, including whole class, team policy, one-on-one and public forum debates. For example, a whole class debate centres on a proposition. Students research all possible perspectives and decide whether to argue for or against. A key aspect of most debating types is effective questioning used to challenge the opposition’s argument. Highly structured debates generally follow the Oxford style. Australian students can choose to practise Parliamentary style debate and engage in Mock Trials among other competitions such as the NSW Premier’s Debating Challenge.

Why debate matters

A political and intergenerational obligation

In a democracy, as one writer has asserted:[7]

Those who would presume to be the embodied representation of the interests, needs, and desires of millions of people owe it to voters to subject themselves to the intellectual rigors of honest debate.

Australian politicians are constitutionally, professionally and morally obliged to engage in high-quality debate, both inside Parliament and in the public square. Debate is an indispensable feature of Australia’s bicameral system of government. Members of the House of Representatives, for example, are reminded that[8]:

By speech and reply, expression and reality are given to all the individualities and political forces brought by popular election into the representative assembly. Speakers alone can interpret and bring out the constitutional aims for which the activity of parliament is set in motion, whether they are those of the Government or those which are formed in the midst of the representative assembly. It is in the clash of speech upon speech that national aspirations and public opinion influence these aims, reinforce or counteract their strength.

Those sitting in Australia’s upper house are advised that “Debate fulfils one of the primary functions of the Senate, that of informing itself and the public by deliberation before decisions are made.”[9]

It is directly associated with a cornerstone of Western civilisation.[10]

The effectiveness of the debating process in Parliament has been seen as very much dependent on the principle of freedom of speech. Freedom of speech in the Parliament is guaranteed by the Constitution,[3] and derives ultimately from the United Kingdom Bill of Rights of 1688.[4] The privilege of freedom of speech was won by the British Parliament only after a long struggle to gain freedom of action from all influence of the Crown, courts of law and Government.

Ideally, such an explicit commitment to democracy is honoured by political leaders who aspire to, and model, high-quality debate, conscious of their accountability to a literate, numerate and well-informed public.

But modelling is not enough. Equally ideally, the example set by Australia’s political leaders is complemented by education policies and practices that prioritise active and informed debate.

Both scenarios assume acceptance of an intergenerational responsibility to pass on nation-building values, knowledge and skills. Australian school education is a logical contributor to this work.

An ancient art for 21st century learners

Researchers point to the ancient origins and enduring role of debate in developing human communication and cognitive skills as well as establishing the bedrock of Western civilisation — freedom of speech.

As Tomperi et al (2023) explain, “debate is one of the most traditional teaching and learning methods, if not the oldest, going back to the ancient educational cultures in Greece and Rome.”[11] Novikoff (2012) echoes this claim: “Debate and argumentation are as ancient as civilization itself, and perhaps innate to the human mind.”[12]

Philosophers of the 5th and 4th centuries BC such as Protagoras, Socrates, Plato, Aristocles, and Aristotle debated profound moral, social and political questions. Of particular concern was how human beings should aspire to live for the benefit of society as well as for themselves. Quintessential and existential issues affecting human flourishing have long underpinned social and political theory and policy making. They are evident at the heart of contemporary notions of equality, justice and the many legislated freedoms to which Western civilisation subscribes.

At its best, the ancient art of debate makes rigorous cognitive and linguistic demands. Protagoras, a teacher of rhetoric for 40 years, is regarded as the ‘father of debate’ who brought argumentation to nascent Greek city-state democracies. He worried about the subjective nature of human knowledge, believing that people understand the world and make judgments according to what they perceive; rendering every judgment relative to that knowledge. Objectivity remains a difficult intellectual practice and must be a conscious goal.

In the works of his successors, Socrates is portrayed as relentless in the pursuit of truth through logic and reasoning. Determined to expose the human propensity for self-interest and deception, he challenged his students to question their own knowledge and assumptions and come to their own conclusions. Contemporary educators have rediscovered the so-called Socratic method as a proven means of testing knowledge and encouraging logic.

In 399 BCE, accused of false teaching and behaving “wickedly”, Socrates is reported to have made three speeches at his trial in which he urged Athenians to challenge the decisions of their leaders. According to Plato, his devoted student, Socrates claimed that “the unexamined life is not worth living for a human being”, reflecting his belief that without reason and the acquisition of wisdom, human beings cannot distinguish between what is good and what is not.[13] After hearing his own death sentence, Socrates reportedly said:

If you suppose that by killing human beings you will prevent someone from reproaching you for not living correctly, you do not think nobly. For that kind of release is not at all possible or noble; rather, the kind that is both noblest and easiest is not to restrain others, but to equip oneself to be the best possible.

Plato (later a teacher of Aristotle) founded what might be regarded as the world’s first university — the Academy of Athens. A sceptic, Plato held that the changeable nature of the world means human beings cannot easily perceive an eternal (or universal) truth. An ethical human existence requires the deliberate consideration of external, abstract and ideal forms of knowledge, such as beauty, justice and goodness, which exist separately from our perceived reality. Debate enables this process.

Another great influencer was Aristotle (384-322 BCE). His Rhetoric explores the art of persuasion, taking into account the speaker, the topic and the audience when communicating and arguing a proposition. Among his other contributions, Aristotle’s work on correct reasoning — logic — was foundational to subsequent generations. These included Cicero (106-43 BCE), regarded as the greatest Roman orator, who emphasised cadence and phrasing in speech.

The intellectual and cultural prestige of rhetoric carried it into the first millennium, with Latin becoming the language of scholars. Rhetoric evolved from its role in public addresses to the application of argumentation and reasoning in new contexts. It was key to emerging concepts of discovery and proof.

Between the sixth and 15th centuries, Latin consolidated its status as the carrier of the intellectual traditions of the ancient world and of Christianity. In medieval Europe, where so much scholarly work took place in monasteries and was guided by theology, the practice of argumentation evolved into an extremely formal, rigorous model known as scholastic disputation.

The importance of logic was reasserted when new translations of Aristotle’s work were completed during the 12th century. Novikoff (2012) explains that this began a cultural evolution “in the early thirteenth century with the institutionalization of disputation as a central component of university education.”[14] Textbooks were written to support the teaching of this practice, emphasising the use of arguments for and against a claim, as well as awareness of fallacy, logic and consequence.

Renaissance thinking brought some scepticism about scholastic disputation, with critics calling the level of Latin used in this practice “cumbersome, artificial and overly technical.”[15] Many did not belong to the university system, where scholasticism was the norm. More interested in rhetoric and persuasion than in logic and demonstration, they advocated for a return to the classical Latin of Cicero and other revered thinkers.

By the 18th century, debating had become more organised, with dedicated societies springing up across Europe. London became a hub for a vibrant debating culture — including in the famous coffeehouses often used by political groups — whose forums often welcomed women and people from wider backgrounds. Debates covered philosophy, the natural sciences and current events, much of this associated with the French Revolution and social upheaval.

The increased interest in public speaking led to more attention being paid to structure, politeness and speech. This was the era of debating societies, in which Irish-born parliamentarian and philosopher Edmund Burke played a crucial role. A liberal thinker for his time, he is now thought of as the father of modern political conservatism. At Trinity College Dublin in 1747, Burke founded a student debating society. In 1770, it merged with the College’s Historical Club to become the College Historical Society (nicknamed The Hist), which celebrated its 250th anniversary in 2019.[16] The then pro-Chancellor, Sir Donnell Deeney, emphasised that

the Hist has been at the forefront of major debates in Irish political, social and cultural life for the past 250 years … now more than ever before, discourse and debate are crucial in a democratic society and must be preserved and celebrated.

These notions reflect profound differences between Western and other political traditions: democratic principles of equality and justice rest on a moral (natural) right to free speech and the right to hear the propositions of others. In turn, this relates to other freedoms, underpinning equality before the law, the pursuit of truth and the administration of justice. Importantly, it is a constraint on governments. In a democracy, the government does not claim ultimate authority to determine what citizens can say, read and hear.

Like Socrates, 19th century English philosopher and politician John Stuart Mill was conscious of the tendency for corrupt leaders to try to suppress free speech, asserting that “they have no authority to decide the question for all mankind.”[17] In On Liberty, he posed the question:

Let Truth and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter?[18]

Democracy is reflected in both freedom of thought and the freedom to communicate those thoughts; it is the ultimate expression of the open exchange of ideas among free and equal citizens. It demands intellectual effort, tolerance and a commitment to the common good. This includes the acceptance of the concept that countering an argument – rather than suppressing it – is a genuine reflection of the commitment to free speech, and through it, to democracy.

Yet one researcher laments that “We’ve all but forgotten that public participation is the very soul of democratic citizenship, and how much it can enrich our lives.”[19] World champion debater and coach of the Harvard and Australian national debate teams, Bo Seo, has commented:[20]

In our age of polarisation, we have lost shared values and truths, but we have also lost the skills of thoughtful, empathic argument – and the will to invest in them. As widespread disillusionment with traditional institutions has coincided with declining confidence in our fellow citizens, an ethic of “finding our people” (and disregarding the rest) has come to dominate.

In a 2022 presentation, bioethicist David van Gend echoed these notions when referring to Western civilisation’s “hard-won civic liberty”[21]:

Free speech — which means free argument — is at the heart of a society that settles its disputes by debate, not by guns.

The ancient art of debate encourages an appreciation of the robust and civil exchange of ideas, always on the basis of knowledge and reason. Notably, this contrasts with the incivility experienced in some forums, particularly online. Cancel culture and political correctness are demonstrably at odds with Western societies that are built on the belief in the human right to freedom of speech.

Benefits in the classroom

Taught well, debate is a uniquely powerful instrument for building students’ appreciation of millennia of Western academic and cultural traditions; particularly in relation to proven ways of constructing and dealing with opposing arguments.

There is strong empirical support for the benefits of debate as a teaching tool. Although much of the research has been conducted in higher education settings, the findings are equally applicable to younger students and relevant to subjects across the curriculum. Numerous studies provide practical examples of how to prepare students to debate, including preparatory exercises (such as research and brainstorming) that require participation by all, how to use online technology in lieu of or to complement in-person debating, and how to design post-debate activities to close the loop.

Debate is a way to demonstrate knowledge using the so-called 21st century skills — or 4 Cs — of communication, collaboration, critical thinking and creativity. With reference to these 21st century skills, former United States Secretary of Education Arne Duncan identified the art of debate as “uniquely suited” to the formation of modern citizens.[22]

A case study from Finland concluded that “When practiced with a firm pedagogical base, debate is a form of experiential learning and, as such, well in tune with contemporary educational psychology.”[23]

Kuhn and Crowell (2014) maintain that “argumentation is a higher-order intellectual skill — an aspect of what is referred to as ‘critical thinking’ — and higher-order thinking skills as educational objectives have been notoriously difficult to achieve.’’[24] Their three-year study involved a curriculum specifically designed to help adolescents learn dialogic argumentation skills. The main objective was to “encourage attention to the other’s position and to enhance one’s ability and disposition to criticize it — in other words, to engage in counter argumentation.”[25] Using instant-messaging software, the students worked in pairs, with the obvious goal being to win each debate. Over time, however, the students became more interested in the quality of the argument and the construction of counterarguments and rebuttals. Following the practical debate phase, the students wrote individual essays and underwent debriefing sessions with the teachers. According to the researchers, this was the first study “to show long-term gains in young adolescents’ dialogic argumentation skills as a function of an intensive and extended multiple-year curriculum devoted to this goal”.[26]

Debating has also been shown to have benefits beyond the stated aims relating to argumentation and critical thinking. For instance, Walker and Kettler (2020) led a study of adolescent students in which debate was used specifically to encourage critical thinking, but the outcomes went beyond that. The students reported better note-taking and listening skills, as well as learning to see multiple perspectives and nuances of the argument. The researchers found evidence of particular benefits for students who demonstrated high cognitive ability at the outset.[27]

But debating need not only benefit the most able students. A seminal review of the empirical evidence is found in a joint project of an international charity, The English-Speaking Union, and the United Kingdom’s Centre for British Teachers (CfBT) Education Trust.[28] Based on concerns about the English literacy skills of school students “who may be comfortable in front of a screen [but] are lacking in the communication skills needed in the workplace and in life,”[29] the review investigated debate as a teaching activity.

Analysis of 51 robust studies from the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, France, Israel, Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong found that “the strongest body of evidence exists around the relationship between participation in debate activities and academic attainment”, especially among young people from diverse backgrounds and “in particular on the development of literacy skills.”[30] For example, American students engaging in debating were 25% less likely to drop out of school than non-debaters and African-American males who participated in debating were 70% more likely to finish high school than their non-debating peers.[31]

Student feedback revealed that “the benefits identified by participants themselves offer support to the idea that debate activities can have academic benefits in terms of increased motivation, engagement and knowledge; the ability to connect their learning with the ‘real world’; and specific skills such as reading and writing, as well as in more general skills such as critical thinking.”[32]

A report from England’s Commission on the Future of Oracy Education (2024)[33] concludes that the

study of speech and debate (perhaps through the study of rhetoric) is a key aspect of oracy education. Complementing their subject-led learning, these practices help students to explore the relationship between persuasion, argumentation and evidence. They learn how arguments can be evaluated in relation to reason; knowledge or fact; and community or audience. As such, speech and debate provide opportunities for students to develop critical thinking and reasoning skills that are of benefit across all curricular learning, and to active citizenship both at school and in later life.

Researchers have made clear links between debating and improved language proficiency. For example, Collier (2004) investigated the use of academic debate in urban high schools, concluding that reading comprehension improved up to 25% among debaters compared to their non-debating peers.[34] Student participation in a competitive debate is linked to improved ability to select evidence and then structure and sum up an argument.[35] Students can achieve better comprehension of complex concepts and develop more sophisticated critical evaluation skills when controversial topics are taught in a debate format rather than through lectures only.[36]

Although debate’s natural home is often considered to be the English or Humanities classroom, numerous studies focus on its use as a teaching technique across the curriculum.[37] According to Bellon (2000), learning the art of debate enhances a student’s capacity to synthesize wide bodies of complex information, to make connections between words and ideas that make concepts more meaningful, and to foster problem solving and innovative thinking.[38] Specific evidence can be found “for a link between debate activities in the classroom and improved subject knowledge in science (biology), history, art and English as a foreign language.”[39] The English-Speaking Union’s joint project reviewers concluded that “using debate as a teaching tool can deliver a greater depth of learning.”[40]

Goodwin (2003) reflects on how well-run debates “invite scrutiny of the widest possible range of alternative views on a subject”,[41] with students reporting that they had to become much more familiar with the content than they might otherwise have done.[42] Debating demands active learning and participation; in turn, this is more likely to help with knowledge retention. In line with ancient debating philosophy and practice, Kennedy (2007) makes the point that “debates require the use of logic and reason rather than merely a free expression of opinions and force participants to be prepared so they know what they are talking about.”[43]

Geographer Ruth Healey identifies debate as a strategy for higher education students to develop the skills to undertake critical analysis — including of controversial topics — from multiple perspectives and to express themselves effectively in speech and in writing.[44] She cites other researchers who maintain that debate provides the “opportunity to stimulate development of their critical thinking through encountering students with views contrary to their own, and in doing so, induce them to either change those views or learn to defend their own views with better logic and more substantial evidence”.[45]

Evidence for “the potential of debating for increasing motivation, language competence and soft skills” is also found in research from Italy.[46] With a particular emphasis on the use of debate for teaching English as a foreign language, Cinganotto (2019) surveyed students and teachers in secondary schools. Both groups were positive, with teachers reporting particular benefits for vocabulary and fluency and students commenting that it was a more innovative, ’real-life’ way to practise language.[47]

The research literature also emphasises the broader philosophical and socio-cultural aspects of debate.[48] Philosopher and Harvard Law School professor Michael Sandel says “we need to rediscover the lost art of democratic argument.”[49] Jerome and Algarra (2006) investigated a high-profile debating competition across London secondary schools, reporting on “research from a range of perspectives, including political education, political philosophy and debate as a teaching method, to clarify the role of debate within a pedagogy for democracy.”[50]

Similarly, Andrew Oros (2007) posits that “apart from pedagogical issues, encouraging students to think through political issues, to discuss them not just with friends but also with those holding different views, and to listen to opposing arguments, enhance citizenship skills vital to a resilient democracy and vibrant civil society.”[51]

These aims are echoed by England’s Commission on the Future of Oracy Education (2024), which argues for increased opportunities for young people to “express their ideas and critically engage with their peers in dialogue, deliberation and debate to prepare young people as active, engaged, and reflective citizens.”[52] The Commission believes “Oracy education can support young people to develop the confidence and agency to advocate for themselves and others and open the minds of young people to a diversity of ideas and perspectives.”[53]

The education policy gap

A federal election heightens debate about the progress of the nation and its people, specifically as measured by the effectiveness of public policy. Despite substantial increases in annual taxpayer expenditure on schooling, too few Australian students are thriving academically. Falling student achievement in national and international assessments is documented in a long series of reviews and reports.[54] The findings undermine the key academic goal of the National School Reform Agreement (2018-2024) signed by all education ministers: “that Australia is considered to be a high quality and high equity schooling system by international standards by 2025.”[55]

The findings can also be viewed against the overarching Education Goals for Young Australians.[56]

Goal 1: The Australian education system promotes excellence and equity

Goal 2: All young Australians become confident and creative individuals, successful lifelong learners, and active and informed members of the community

The interconnection of these two goals can quickly be inferred: excellent educational opportunities and outcomes are associated with higher levels of individual confidence, creativity, motivation to continue to learn and the capacity to make a civic contribution to the nation. By definition, succeeding at both national goals relies on proficiency in English.

Furthermore, Goal 2 details the intention to develop students who:[57]

have an understanding of Australia’s system of government, its histories, religions and culture;

and

are committed to national values of democracy, equity and justice, and participate in Australia’s civic life by connecting with their community and contributing to local and national conversations.

The convergence of language skills and knowledge determines an individual’s capacity to “participate in Australia’s civic life … by contributing to local and national conversations.” One obvious way for young Australians to do this is to engage in debate.

Australia’s national curriculum reflects the national education goals. That document “identifies and organises the essential knowledge, understandings and skills that students should learn in 8 learning areas.”[58]

It must be noted, however, that Australia’s eight states and territories are free to ‘adopt and adapt’ the Australian Curriculum and can choose their own timelines for implementation. Each state and territory is unique in its management of academic expectations, student reporting, teacher professional development and, perhaps most importantly, the assessment and qualifications applicable to senior secondary students (Years 11 and 12).

Australia’s literacy and numeracy reality

Proficiency in English is the basis on which students can make constructive subject choices and achieve academic success across the wider curriculum. Conversely, low levels of competence and confidence in English present a constant barrier to choice and academic progress. The same is true of Mathematics. A lack of proficiency in these two subjects means many school leavers will struggle to become active and informed members of the community.

A series of reports explains how national and international test results reveal a decline in students’ literacy and numeracy.[59] For example, a 2008 analysis conducted by Australian National University economists concluded that literacy and numeracy performance had not improved since the 1960s, in spite of a 258% increase in government spending over the four decades between 1964 and 2003.[60] Similarly, analysis of Australian students’ PISA results revealed that “In mathematics and reading … 15-year-olds in 2022 scored at a level that would have been expected of 14-year-olds, 20 years earlier.”[61] In 2023, the Productivity Commission echoed that theme, stating that “Academic achievement of Australian school students has stagnated over the past decade … the lack of improvement in academic results has been accompanied by a concurrent increase in the amount of money spent on schools.”[62]

The 2024 NAPLAN results indicate that about 450,000 students in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 could not meet proficiency standards across a range of literacy and numeracy tests. This follows a 2023 revelation that one in three Australian students in primary and secondary schools could not read to the minimum standard, with Grattan Institute research concluding that this would bring a cumulative national cost to the nation of $40 billion.[63]

Moreover, in the most recent 10-yearly study by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, 44% of Australian adults were found to have low reading skills in English, with only 15% able to demonstrate high proficiency.[64]

Understanding Australian democracy

Australian students in Years 6 and 10 take part in sample testing as part of the triennial National Assessment Program – Civics and Citizenship (NAP-CC). Held every three years, these tests measure “students’ skills, knowledge and understandings of Australian democracy and its system of government, the rights and legal obligations of Australian citizens and the shared values which underpin Australia’s diverse multicultural and multi-faith society.”[65]

Since NAP-CC testing began in 2010, Year 10 results have steadily declined. In 2019, only 38% of students performed at or above the proficient standard. There are concerns that students not only lack content knowledge but also struggle with the English language demands of the questions. Due to the COVID pandemic, no testing was undertaken in 2022.

It must be noted that these students are approaching the end of compulsory schooling, a point at which they make decisions about continuing into senior secondary programs (Years 11 and 12) or leaving school to embark on another education pathway or into the workforce. They will soon be eligible to vote.

There is no requirement for students in Years 11 and 12 to study civics. Yet the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Declaration states that:[66]

Australian Governments commit to working with the education community to provide a senior secondary education that equips young people with the skills, knowledge, values and capabilities to succeed in employment, personal and civic life.

In March 2024, evidence of young Australians’ poor understanding of their nation’s governance led to a decision by The Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM)[67] to establish an inquiry into:

the effectiveness of formalised civics education throughout Australia and the various approaches taken across jurisdictions through schools and other institutions including electoral commissions, councils, and parliaments; the extent to which all students have equitable access to civics education; and opportunities for improvement.

Given the evidence for the benefits of debate for consolidating knowledge, a logical strategy would be to strengthen its presence in the Civics and Citizenship component of the Australian Curriculum.

The place of debate in the Australian Curriculum

Australia’s national curriculum for students in Foundation to Year 10 consists of eight learning areas, seven General Capabilities and three Cross-Curriculum Priorities.

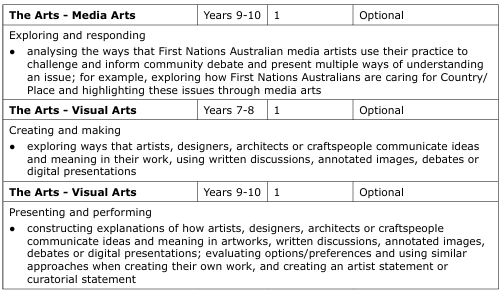

That there are at least a few references scattered across these three dimensions indicates that the Australian Curriculum acknowledges the contribution that the art of debate can make to teaching and learning.

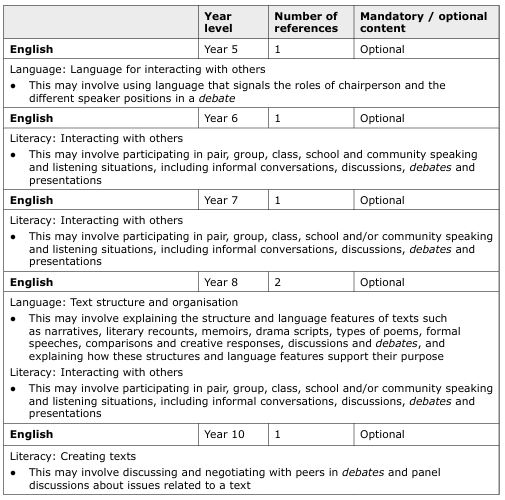

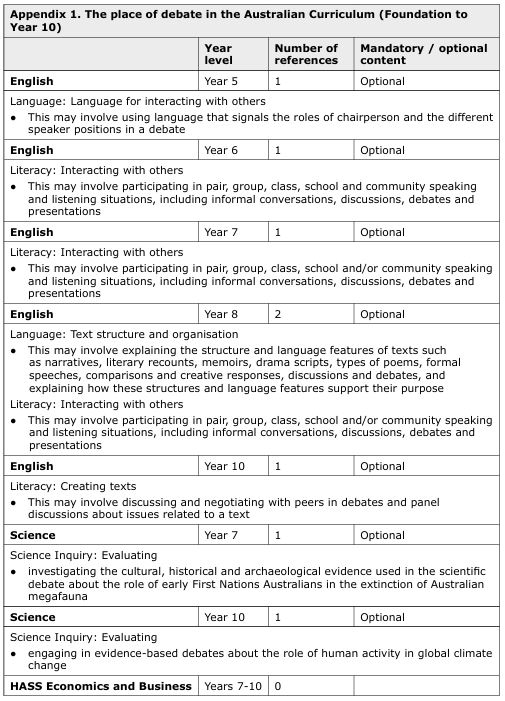

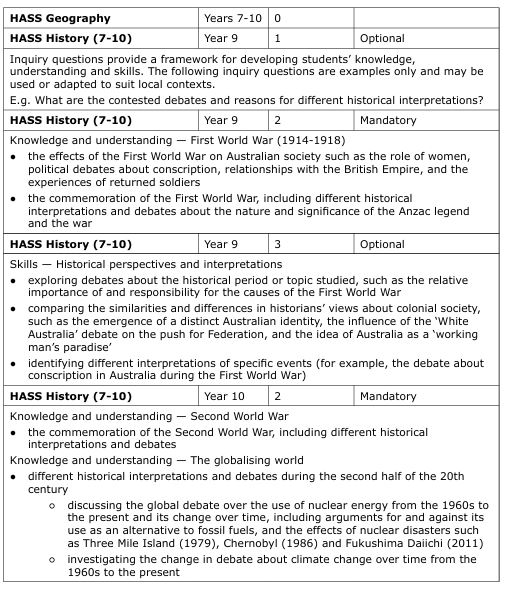

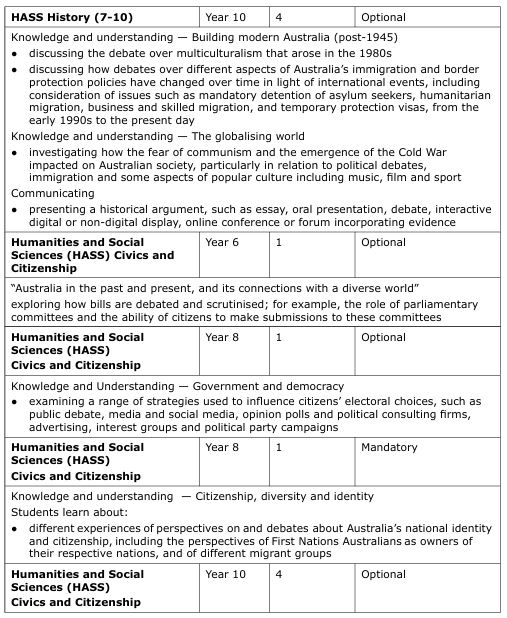

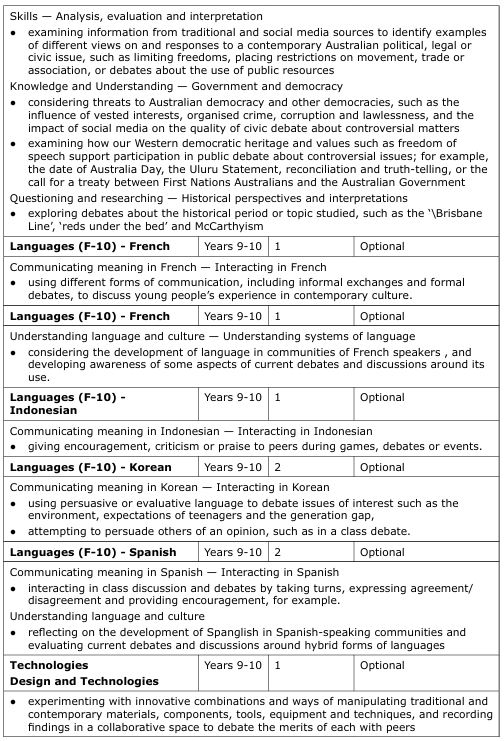

As can be seen in Appendices 1 and 2, almost all references to debate are optional content, meaning that any emphasis on this skill will depend on the interest and knowledge of the teacher.

English

In the subject of English, for example, the Australian Curriculum for Foundation to Year 10 may involve students in debating.

Table 1: The place of debate in the English learning area of the Australian Curriculum (Foundation to Year 10)

Appendix 1 lists references to debate in other learning (subject) areas.

Civics and Citizenship

Civics and Citizenship is one component of the Australian Curriculum. The rationale for its study is:[68]

A deep understanding of Australia’s federal system of government and the liberal democratic values that underpin it is essential for students to become active and informed citizens who can participate in and sustain Australia’s democracy.

This component of the Australian Curriculum (Years 7-10) aims to develop various skills, including communicating. It appears as one of the Key Considerations for teachers:[69]

Students explore contemporary issues through approaches such as class discussions, debates, civic action, role-plays, volunteering, student participatory research, community service and advocacy.

No explicit links are made between debate and the fundamental rights and practices of individuals in a democracy. Notably, the word democracy appears just once in the 13-page Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Declaration, in one of eight dot points under Goal 2. The Declaration remains one of the most influential Australian education road maps, underpinning the Australian Curriculum and its state and territory counterparts.

This lack of emphasis may help to explain the varying levels of support for shared values. For example, according to the 2024 Lowy Institute Poll, “younger Australians aged 18–44 (65%) are less likely than older Australians aged over 45 (79%) to say democracy is preferable to any other kind of government — a 14-point gap that has widened by five points since 2022.”[70]

By way of contrast, the world’s highest-performing education system asserts that “schools are a valued space to integrate our multicultural community with an emphasis on shared values and to nurture active and committed citizens who are rooted to our nation.”[71]

Referred to as “the bedrock upon which Singapore’s education system stands”, Character and Citizenship Education (CCE) is a priority in that country’s curriculum and approaches to teaching and learning. Since 2023, CCE has had its own home in the Singapore Centre for Character and Citizenship Education at the National Institute of Education (NIE).[72]

CCE cannot be perceived in a silo or taught as a subject. Instead, the educational experience that we provide in our schools for our students needs to facilitate the coherent development of character and citizenship dispositions, and social-emotional well-being, across the total curriculum.

The Singaporean “citizenship dispositions” are A sense of belonging, A sense of Reality, A sense of Hope, and The Will to Act.[73]

General capabilities and cross-curriculum priorities

In addition to the eight learning (subject) areas, there are seven General Capabilities, which comprise a separate dimension of the Australian Curriculum. These are expected to be incorporated into the teaching in each learning area. These skills and attributes are allegedly essential for students in the new millennium and reflect the 21st century learning agenda.

- Critical and Creative Thinking

- Ethical Understanding

- Intercultural Understanding

- Literacy

- Numeracy

- Personal and Social Capability

- Digital Literacy (previously Information and Communication Technology)

Critical and Creative Thinking is designed around four elements (Inquiring, Generating, Analysing and Reflecting), which would seem a logical place for a focus on debating.

The Cross-Curriculum Priorities, a third dimension of the Australian Curriculum, are:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures

- Asia and Australia’s Engagement with Asia

- Sustainability

As with the General Capabilities, the CCPs offer considerable scope for the development of debating skills.

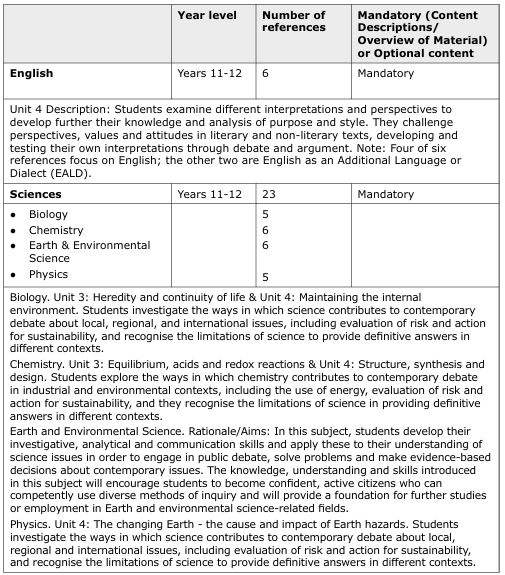

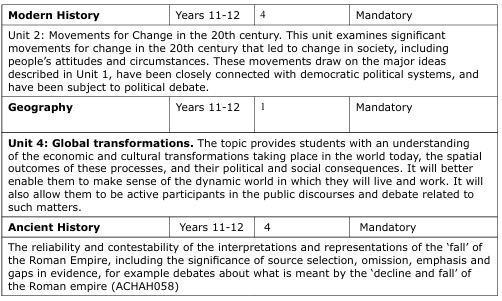

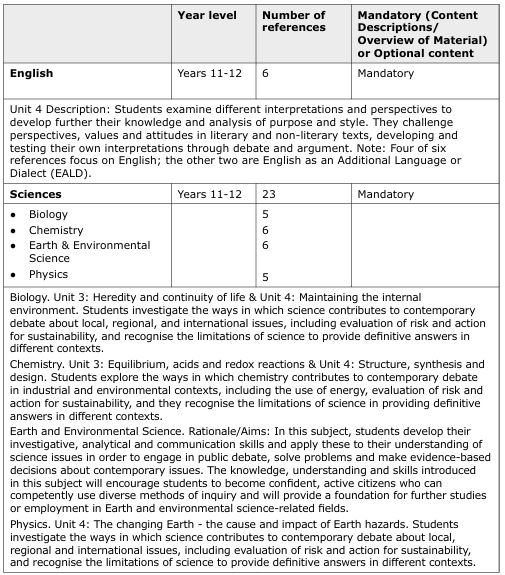

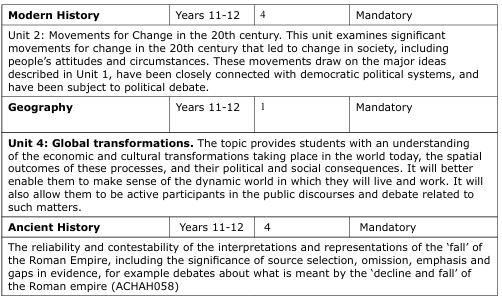

Senior secondary

Although the Australian Curriculum also sets expectations for senior secondary subjects, each Australian state and territory makes its own arrangements regarding curriculum, assessment and qualifications for students in Years 11 and 12. Any analysis of the Australian Curriculum for these year levels does not necessarily reflect what is taught or emphasised in the senior secondary certification across the states and territories.

A key word search for ‘debate’ in the Australian Curriculum for senior secondary students reveals some three dozen references. The majority of references are in the Content descriptions, which mandate material for study.

As can be seen in Table 2, the learning areas of English, Mathematics, the Sciences and Humanities and the Social Sciences (HASS) vary in their expectations of how debate might be incorporated. Ideally, a clear continuum of teaching and learning, across Foundation to Year 12, would build English language proficiency and subject knowledge as part of the practice of debating.[74]

In English and Geography, for example, these older students are encouraged to practise the art of debating. In the Sciences, students explore ways in which a field of knowledge contributes to contemporary debate, but there is no requirement to actually practise debating. The Modern History curriculum challenges students to examine and interpret significant ideas and events of the 20th century, focusing on how these fuelled political debate. However, they are not invited to test their own interpretations through active debate.

Table 2: The place of debate in the Australian Curriculum: Senior Secondary

Debating as an extra-curricular activity

While some enthusiastic teachers may have debate in their pedagogical tool kit, it is generally offered as an extra-curricular activity for students, making it totally dependent on a school’s level of interest and the availability of suitable coaches and external (including online) debating forums.

By extension, this means access to debate is highly inequitable: high-functioning and well-resourced schools can afford to dedicate time and money to these activities, but many other schools — and therefore students — will go without.

According to the Australian Debating Federation, about 30,000 Australian students participate in debating competitions each year.[75] The ADF claims that:

Debating training imparts lifelong skills to students, including confidence in speaking in public to peers, an ability to logically make and assess arguments, and a willingness to engage with, and learn from, those with different opinions.

For over 100 years, the London-based English-Speaking Union (over 50 member countries, including Australia) has provided training and forums for young people to learn to debate. The ESU emphasises that “Language, a powerful tool that transcends borders and connects individuals from diverse backgrounds, has played a pivotal role in shaping global communication.”[76]

In 2023, the English-Speaking Union of New South Wales (ESU NSW) celebrated its centenary at Government House in Sydney. Australia’s affiliation with this international debating body is explained on the ESU Australia website[77]:

We believe that the ability to progress and to thrive in life relies on oracy — speaking and listening — skills, which are not currently a prominent part of the school curriculum.

Giving debating a prominent place in the curriculum is a logical strategy for achieving the national goals of excellence and equity in both English language and civics and citizenship.

Conclusion and recommendations

As is true of education systems across the globe, curriculum standards and the teaching practices associated with these must evolve and innovate in order to prepare young learners for their post-school lives. Australian students’ unsatisfactory achievement in both English language and civics and citizenship is under scrutiny. Success in both these subject areas is essential to individual progress and national prosperity.

This paper identifies a proven strategy for enhancing Australian students’ English language proficiency and overall academic performance as well as their formation as active and informed citizens.

As Australian school education undergoes yet another wave of reform — this one focused on the rehabilitation of traditional approaches to the acquisition of knowledge through well-structured curriculum and explicit teaching — a heightened emphasis on the ancient art of debating is both logical and urgent.

Taught well, debating develops cognitive, linguistic, socio-cultural and interpersonal knowledge and skills. The historical and empirical evidence make a clear case for its use across the curriculum.

Beyond its practical application in the classroom, the art of debate is a commitment to the most profound and enduring Western traditions, including freedom of speech and the robust, civil exchange of ideas.

- Design a framework for Australian school education that provides a succinct intellectual, philosophical and academic foundation for the curriculum. The framework will:

-

- clarify the academic expectations for students throughout the compulsory and post-compulsory years of schooling

- align with, and be a clear and useful manifestation of, Australia’s national education goals

- reflect deep and unifying themes to be embedded across the curriculum, including Australia’s official national values

- specify the use of evidence-based approaches to pedagogy (such as debating) with particular emphasis on English language proficiency and civics and citizenship

- include clear rationales for curriculum and pedagogical decisions

- provide clear and practical guidance for curriculum writers

- ensure a clear line of sight between the national goals and strategies for meeting curriculum expectations, including initial teacher education, academic leadership and professional development

- Prioritise debating in literacy strategies and frameworks as a means of improving English language and academic research skills and enhancing critical thinking.

- Obtain a commitment from university initial teacher education providers to ensure that all graduates can demonstrate competence and confidence in debating as a pedagogical tool for use across the curriculum.

- Encourage jurisdictions to collaborate with credentialled debating organisations to provide ongoing professional development for principals and teachers.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

The place of debate in Australian Curriculum (Senior Secondary): Samples

Endnotes

[1] Jha, T. (15 February 2024) What is the Science of Learning? Centre for Independent Studies. https://www.cis.org.au/publication/what-is-the-science-of-learning/

[2] Australian Education Research Organisation. (2024). A knowledge-rich approach to curriculum design.

https://www.edresearch.edu.au/research/research-reports/knowledge-rich-approach-curriculum-design

[3] As background, see Thornhill-Miller B et al. ‘Creativity, Critical Thinking, Communication, and Collaboration: Assessment, Certification, and Promotion of 21st Century Skills for the Future of Work and Education’. Journal of intelligence. 2023 Mar 15;11(3):54.

[4] Tumposky, N. R. (2004) ‘The Debate Debate’, The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 78(2), p. 52.

[5] Ibid.

[6] ACARA. (accessed November 2024) Review of the Australian Curriculum https://www.acara.edu.au/curriculum/curriculum-review

[7] DeWitt, D. (1 September 2022) ‘Healthy public debate is the essence of democracy’ Ohio Capital Journal.

[8] Parliament of Australia. (2023) House of Representatives Practice (7th Edition), Chapter 14 – Control and Conduct of Debate. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/House_of_Representatives/Powers_practice_and_procedure/Practice7/HTML/Chapter14/Control_and_conduct_of_debate

[9] Parliament of Australia. (2023) Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, Chapter 10 – Debate. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Senate/Powers_practice_n_procedures/Odgers_Australian_Senate_Practice/Chapter_10

[10] Parliament of Australia. (2023) House of Representatives Practice (7th Edition), Chapter 14 – Control and Conduct of Debate. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/House_of_Representatives/Powers_practice_and_procedure/Practice7/HTML/Chapter14/Control_and_conduct_of_debate

[11] Tomperi, T., Korhonen, O. & Mielityinen, S. (2023) ‘Debate as a Pedagogical Practice: A Case Study from Finland on Teaching International Law’’ Journal of Legal Education, Volume 72, Numbers 1 & 2, p. 156

[12] Novikoff, Alex J. (1 April 2012) Towards a Cultural History of Scholastic Disputation. The American Historical Review. Volume 117, Issue 2, p. 335 https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article/117/2/331/30024

[13] Cornell University Press. (1979) Reprinted (with revisions) from Thomas G. West, Plato’s Apology ‘of Socrates: An Interpretation with a New Translation, p.20.

[14] Novikoff, Alex J. (1 April 2012) Towards a Cultural History of Scholastic Disputation. The American Historical Review. Volume 117, Issue 2, p. 349 https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article/117/2/331/30024

[15] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (accessed 14 October 2024) Historical Supplement: Argumentation in the history of philosophy https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/argument/supplement.html

[16] Trinity College Dublin. (15 March 2019) Historical Society launches Hist250 celebrations https://www.tcd.ie/news_events/articles/historical-society-launches-hist250-celebrations/

[17] Mill, John Stuart. (1859) On Liberty, London: John W. Parker and Son. [Mill 1859 available online]

[18] Ibid

[19] Miroff, B., Seidelman, R., & Swanstrom, T. (2012) Debating Democracy – A Reader in American Politics (7th Edition) Wadsworth Cengage Learning, p. 39.

[20] Seo, B. (4 September 2022) The art of debating taught me to see another view – it’s a skill that brings people together. The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2022/sep/03/the-art-of-debating-taught-me-to-see-another-view-it-is-a-skill-that-brings-people-together

[21] van Gend, D. (2022) ‘Citizens of no mean city.’ 7th Colloquium – The Christopher Dawson Centre for Cultural Studies. Hobart https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eEgmXRX8RVc

[22] The power of speech and debate education (2024). Stanford National Forensic Institute. https://snfi.stanford.edu/skills

[23] Tomperi, T., Korhonen, O. & Mielityinen, S. (2022-2023) ‘Debate as a Pedagogical Practice: A Case Study from Finland on Teaching International Law’ Journal of Legal Education, Volume 72, Numbers 1 & 2, p. 156

[24] Kuhn, D. & Crowell, A. (30 April 2014) ‘Developing Dialogic Argumentation Skills: A 3-year Intervention Study. Journal of Cognition and Development, 15(2), p. 363

[25] Ibid., p. 365

[26] Ibid., p. 377

[27] Walker, A., & Kettler, T. (2020). Developing critical thinking skills in high ability adolescents: Effects of a debate and argument analysis curriculum. Talent, 10(1), p 36

https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/1170808

[28] Akerman, R. and Neale, I. (2011) Debating the evidence: An international review of current situation and perceptions. CfBT Education Trust and The English-Speaking Union. (accessed 1 October 2024) https://www.edt.org/research-and-insights/debating-the-evidence-an-international-review-of-current-situation-and-perceptions/

[29] Ibid, p. 6

[30] Ibid, p. 28

[31] Ibid, p. 12

[32] Ibid, p. 19

[33] Oracy Education Commission. (October 2024) We need to talk. Report of the Commission on the Future of Oracy Education In England, p. 16 https://oracyeducationcommission.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/We-need-to-talk-2024.pdf

[34] Collier, L. (2004). Argument for Success: A Study of Academic Debate in the Urban High Schools of Chicago, Kansas City, New York, St. Louis and Seattle. Paper presented at the Hawaii International Conference on Social Sciences, Honolulu

[35] Jerome, L. and Algarra, B. (2006). English-Speaking Union London Debate Challenge: 2005–06 Final Evaluation Report. Cambridge and Chelmsford: Anglia Ruskin University.

[36] Omelicheva, M. Y., & Avdeyeva, O. (2008). Teaching with lecture or debate? Testing the effectiveness of traditional versus active learning methods of instruction. PS: Political Science & Politics, 41(03), 603-607. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232027470_Teaching_With_Lecture_or_Debate_Testing_the_Effectiveness_of_Traditional_Versus_Active_Learning_Methods_of_Instruction

[37] Goodwin, J. (2003) ‘Students’ Perspectives on Debate Exercises in Content Area Classes’, Communication Education, 52(2), pp. 157–163.

https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=bHPWtxsAAAAJ

[38] Bellon, J. (2000). A research-based justification for debate across the curriculum. Argumentation and Advocacy, 36 (3), 161-173.

[39] Ibid, p. 5

[40] Ibid, p. 9

[41] Goodwin, J. (2003) ‘Students’ Perspectives on Debate Exercises in Content Area Classes’, Communication Education, 52(2), p. 12 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236632746_Students%27_Perspectives_on_Debate_Exercises_in_Content_Area_Classes

[42] Ibid, p.10

[43] Kennedy, R. (2007) In-Class Debates: Fertile Ground for Active Learning and the Cultivation of Critical Thinking and Oral Communication Skills. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Vol. 19, No. 2, p. 185 https://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/pdf/IJTLHE200.pdf

[44] Healey, R. L. (2012) ‘The Power of Debate: Reflections on the Potential of Debates for Engaging Students in Critical Thinking about Controversial Geographical Topics’, Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 36(2), pp. 239–257. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239794646_The_Power_of_Debate_Reflections_on_the_Potential_of_Debates_for_Engaging_Students_in_Critical_Thinking_about_Controversial_Geographical_Topics

[45] Green, C.S. & Klug, H. (1990) Teaching critical thinking and writing through debates: an experimental evaluation, Teaching Sociology, 18, pp. 462-471.

[46] Cinganotto, L. (October 2019) Debate as a Teaching Strategy for Language Learning (Lingue e Linguaggi) Universita per Stranieri di Perugia https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336836038_DEBATE_AS_A_TEACHING_STRATEGY_FOR_LANGUAGE_LEARNING_Lingue_e_Linguaggi

[47] Ibid, p. 117

[48] Oros, A. L. (2007) ‘Let’s Debate: Active Learning Encourages Student Participation and Critical Thinking’, Journal of Political Science Education, 3(3), pp. 293–311. https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=DH_N6XsAAAAJ

[49] Sandel, M. (2013) The lost art of democratic debate. TED-Ed.

[50] Jerome, L. and Algarra, B. (2005) ‘Debating debating: a reflection on the place of debate within secondary schools’, The Curriculum Journal, 16(4), pp. 493–508.

[51] Oros, A. L. (2007) ‘Let’s Debate: Active Learning Encourages Student Participation and Critical Thinking’, Journal of Political Science Education, 3(3), pp. 293–311. https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=DH_N6XsAAAAJ

[52] Oracy Education Commission. (October 2024) We need to talk. Report of the Commission on the Future of Oracy Education In England, p.36 https://oracyeducationcommission.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/We-need-to-talk-2024.pdf

[53] Ibid

[54] For example: Australian Government. Productivity Commission. (December 2022) Review of the National School Reform Agreement (Study Report) https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/school-agreement/report/school-agreement.pdf ; Australian Government. Through Growth to Achievement – report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools (2018) https://www.education.gov.au/quality-schools-package/resources/through-growth-achievement-report-review-achieve-educational-excellence-australian-schools ; Australian Government. Independent Review into Regional, Rural and Remote Education (2017) https://www.education.gov.au/recurrent-funding-schools/independent-review-regional-rural-and-remote-education#toc-the-review

[55] Australian Government. Productivity Commission. (December 2022) Review of the National School Reform Agreement – Study Report, p. 9 https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/school-agreement/report/school-agreement-overview.pdf

[56] Education Council. Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Declaration. (2019) p.4 https://www.education.gov.au/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration/resources/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration

[57] Ibid., p. 6

[58] ACARA. (accessed 24 October 2024) Australian Curriculum https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/f-10-curriculum-overview/learning-areas

[59] See, for example: ACER (2023) Australian teenagers record steady results in international tests, but about half are not meeting proficiency standards https://www.acer.org/au/discover/article/australian-teenagers-record-steady-results-in-international-tests-but-about-half-are-not-meeting-proficiency-standards; ACER (2019) PISA 2018: Australian student performance in long-term decline https://www.acer.org/au/discover/article/pisa-2018-australian-student-performance-in-long-term-decline ;

[60] Leigh, A. & Ryan, C. (February 2008) How has School Productivity Changed in Australia? Australian National University – Research School of Social Sciences. http://andrewleigh.org/pdf/SchoolProductivity.pdf

[61] OECD. (5 December 2023) PISA 2022 Results (Volumes I and II) Country Notes: Australia https://www.oecd.org/en/countries/australia.html

[62] Australian Government – Productivity Commission. (7 February 2023) Report No. 100: 5-year Productivity Inquiry: From learning to growth (Inquiry report – volume 8) https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/productivity/report/productivity-volume8-education-skills.pdf

[63] Hunter, J. (12 February 2024) ‘Australia’s reading fail’. Published in the Australian Financial Review. https://grattan.edu.au/news/australias-reading-fail/

[64] Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2024) Statistics – Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (2011-2012) https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/programme-international-assessment-adult-competencies-australia/latest-release

[65] ACARA. (2019) NAP Civics and Citizenship 2019 National Report, p . 16 https://nap.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/20210121-nap-cc-2019-public-report.pdf

[66] Education Council. Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Declaration. (2019) p.9 https://www.education.gov.au/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration/resources/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration

[67] Parliament of Australia. (2024) Parliamentary Business – Joint Standing Committee into Electoral Matters. https://www.aph.gov.au/CivicsEducation

[68] ACARA. Australian Curriculum (Version 9) – Civics and Citizenship. (accessed 2 October 2024) https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/teacher-resources/understand-this-learning-area/humanities-and-social-sciences#civics-and-citizenship-7-10

[69] Ibid

[70] Neelam, R. (2024) Lowy Institute Poll – 20th Edition https://poll.lowyinstitute.org/files/lowyinsitutepoll-2024.pdf

[71] SingTeach. (2024) National Institute of Education – Office of Education Research. Character and Citizenship Education. https://singteach.nie.edu.sg/2023/10/19/the-crucial-role-of-character-and-citizenship-education-in-singapore/

[72] SingTeach. (2024) National Institute of Education – Office of Education Research. https://singteach.nie.edu.sg/2023/10/19/the-crucial-role-of-character-and-citizenship-education-in-singapore/

[73] Ministry of Education – Singapore. National Education. (accessed October 2024) https://www.moe.gov.sg/education-in-sg/our-programmes/national-education

[74] See Appendices 1 and 2

[75] The Australian Debating Federation. (2024) https://www.debating.org.au/

[76] English Speaking Union Australia (accessed 27 September 2024) Our mission. https://esuaus.org.au/mission/

[77] Ibid