To what extent do Australians think speech is free in this country? According to polling conducted for the Centre for Independent Studies in December 2022, Australians are evenly divided in their views about freedom of speech. The views of those who think speech is unduly restricted appears to be balanced, for the most part, by those who support restrictions if they serve to protect the interests of those members of society considered vulnerable.

However, the authors argue that these results are also open to the interpretation that Australians are fundamentally ambivalent about freedom of speech: we support freedom of speech when we agree with the opinions voiced but are inclined to withdraw that support when we do not agree the views and opinions expressed by others. Constraints on freedom of speech in Australia remain an issue of concern. However, the authors of this report argue that polling suggests there is no ‘crisis’ of free speech and that there is no call for heavy corrective action by government.

Introduction: freedom of speech

The travails besetting Elon Musk and his recent efforts at running the Twitter platform he acquired for US$44 billion in 2022, have re-ignited interest in the issue of freedom of speech. In particular, attention has focused on the kind of trade-offs that need to be made if online speech is to be free while at the same time adequately protected. As The Economist remarked when taking stock of the status of freedom of speech on online platforms:

Free expression is not a problem with a solution bounded by the laws of physics that can be hacked together if only enough coders pull an all-nighter. It is a dilemma requiring messy trade-offs that leaves no one happy.[1]

Any approach to protecting the fundamental human right of freedom of speech necessarily entails recognising that the right often conflicts with other rights, such as the right not to be discriminated against on grounds of race, gender or sexual orientation.

In Australia, the plight of Andrew Thorburn, the Christian business leader Essendon football club hired as CEO but dismissed 24 hours later, provides a good example of such conflict.

Thorburn’s ‘sin’ was to have been associated with a church which neither affirmed nor approved of same-sex relationships. Thorburn himself had never publicly expressed a view on this matter; but his association with a church which had expressed views publicly was enough to finish his career at Essendon.[2]

Was Thorburn entitled to hold an opinion on human sexuality? Should his position have been defended on the grounds of protections afforded by the right to religious freedom? And if so, why was Thorburn’s right trumped by the right enjoyed by another social group not to be discriminated against?

Opinion about Thorburn’s fate divided, and revealed deep differences among, Australians.[3] For some, protecting the sensibilities of LGBTQI+ people was paramount and warranted what was deemed a just — if somewhat harsh — outcome. For others, denying Christians the freedom to express openly their religious beliefs about human sexuality (something which Thorburn himself had not even done, of course) was deemed unacceptably censorious.

A report published by the CIS in December 2019, which was based on other polling commissioned from YouGov, called into question the commitment of Australians to protecting religious liberty. The report observed that preservation of religious liberty requires preservation of the distinctiveness of religious institutions and communities:

To maintain their distinctiveness, such institutions and communities need to have the freedom to select their members and employees on religiously grounded criteria. Without this freedom being protected in some way from the increasing reach of anti-discrimination law, those institutions and communities will not be able to fulfill their roles and functions.[4]

However, at issue in the Thorburn affair was not just the health of religious liberty in Australia. The Essendon saga also showed that Australians seemed to be wavering in their commitment to one of the other fundamental human rights upon which the free exercise of religious liberty depends — free exercise of the right to freedom of speech.

In order to determine the attitudes of Australians towards freedom of speech, the Centre for Independent Studies commissioned YouGov to poll 2169 Australians in December 2022, with the data weighted by a number of factors, including age, gender, education, socio-economic status and religion. This resultant paper provides an important insight into just what Australians think about the extent to which speech is free in this country. Before presenting a more detailed analysis of the results, it will be helpful to give an overview of what the poll disclosed about attitudes to freedom of speech in Australia.

Snapshot of the YouGov poll results on freedom of speech

Results from the YouGov poll show that Australians are evenly divided about the extent to which they consider the right to freedom of speech to be secure.

Among family, 87 per cent feel free to express their views openly, while 84 per cent feel free among friends. In the workplace, by contrast, only 44 per cent of those surveyed considered themselves free to do so.

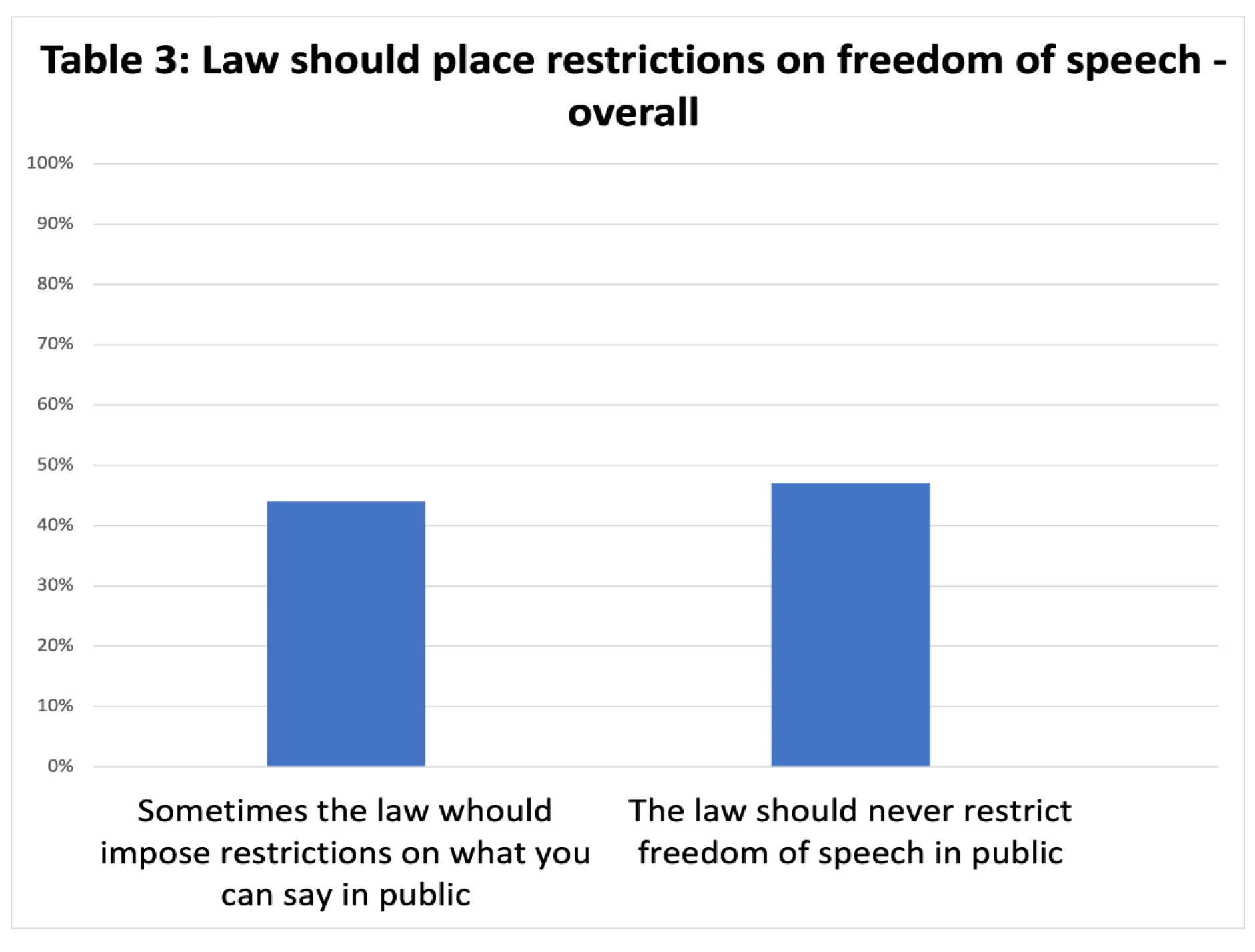

When it comes to whether or not the law should restrict what one can say in public, Australians were similarly divided: 44 per cent of those surveyed thought some legal restrictions were necessary sometimes whereas 47 per cent thought the law should never impose restrictions on freedom of speech in public.

Political correctness was considered beneficial by 44 per cent because it offered important protections to the rights of certain groups. By contrast, 42 per cent considered political correctness mostly harmful because it imposes unfair restrictions on free speech.

When it comes to protecting religious freedom, 46 per cent thought Australian protections were at about the right level, whereas only 15 per cent thought protections were not adequate, and 26 per cent of those surveyed thought Australia did too much to protect the religious sensibilities of others.

Satisfied that religious freedom already enjoys adequate protection, 54 per cent of those surveyed thought that when hiring staff, faith-based schools should not be allowed to discriminate against job applicants. Only 37 per cent thought that religious schools should be free to hire only those who shared the school’s beliefs. These results suggest that the concerns expressed by the authors of the earlier CIS report, referred to above, regarding the need for faith-based organisations in Australia to be afforded protection from the reach of anti-discrimination laws were both reasonable and prescient.[5]

Opinion diverged when respondents were asked about the extent to which members of three principal faiths — Christianity, Islam and Judaism — experienced discrimination. Whereas only 32 per cent thought Christians experienced discrimination, this number was much higher for Muslims (70 per cent) and Jews (54 per cent). 59 per cent of respondents thought Christians faced little, if any, discrimination but this number was correspondingly lower for Muslims (22 per cent) and Jews (35 per cent).

A criticism frequently voiced about so-called ‘woke’ culture is that it generates a heightened sensitivity to divergence of opinion. Whereas only 10 per cent of respondents thought Australian society was not sensitive enough to such opinion, 35 per cent approved of our levels of sensitivity but 45 per cent thought our society was overly sensitive.

In general, the results of the CIS/YouGov poll support the conclusion drawn by this paper that opinion about freedom of speech in Australia is evenly divided. The views of those who think speech is unduly restricted appears to be balanced, for the most part, by those who support restrictions if they serve to protect the interests of those members of society considered vulnerable.

However, as this paper will argue, these results are also open to the interpretation that Australians are fundamentally ambivalent about freedom of speech: we support freedom of speech when we agree with the opinions voiced but are inclined to withdraw that support when we do not agree with the views and opinions expressed by others.

Expressing oneself openly

Respondents were asked how free they felt to express their “true opinions and beliefs about politics” in a number of different environments. Not surprisingly, 87 per cent said they felt free to express themselves openly with family and 84 per cent felt free to do so with friends. A small number of respondents (3 per cent) reported that they were not at all free to express themselves openly with either family or friends.

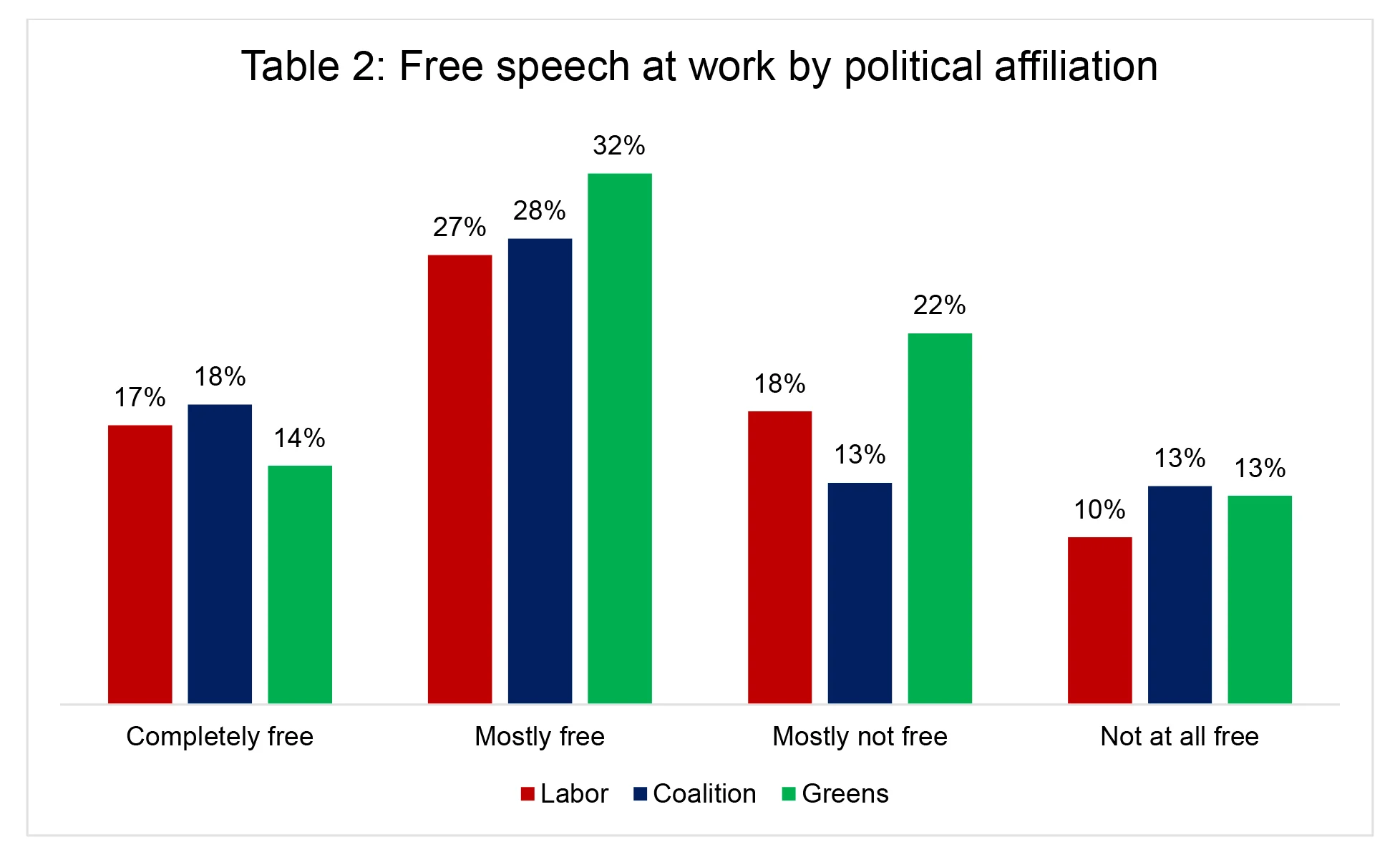

However, responses were different when it came to the workplace: only 44 per cent felt free to express themselves openly at work; while 16 per cent felt they were mostly not free and 11 per cent felt they were not at all free to do so.

Responses were reasonably consistent across all variables such as political affiliation, religious affiliation, gender, age and level of education. For example, 10 per cent of those identifying as ALP supporters said they did not feel free to express themselves openly at work as compared with 13 per cent of Coalition and Greens supporters.

These results suggest Australians are increasingly circumspect about expressing opinions openly in front of colleagues in the workplace where corporate constraints are frequently imposed to enforce policies about diversity, inclusiveness and hate speech. A stumble at any one of those tripwires can be enough to derail or even terminate a career. Accordingly, people watch what they say when speaking to those who are neither family members nor friends. It is easier and more comfortable to speak openly when among family and friends where no diversity policies are being enforced. Polling results suggest this may be so, regardless of political affiliation.

Legal restrictions on public freedom of speech

Although the consequences of breaching them can be severe, workplace policies about diversity, inclusiveness and hate speech clearly do not have the same moral or legal status as laws enacted by parliament. Nor do such policies face the same kinds of obstacle to reform or repeal as those which face legislation.

Whereas workplace policies only have application in the place of employment, it is clear that legal constraints upon freedom of speech can apply both in the workplace and beyond in the public realm. When respondents were asked whether “the law should restrict what you can say in public”, the results showed that Australians are evenly divided about this issue.

Some degree of legal restriction on what can be said in public was supported by 44 per cent of respondents whereas 47 per cent of respondents thought “the law should never restrict freedom of speech in public.”

These results, indicating comparable support for the different viewpoints, were consistent across all variables when controlled for age, household income, educational level and religious affiliation. For example, in response to the proposition “Sometimes the law should impose restrictions on what you can say in public”, 42 per cent of those in the 18-24 age group agreed (the lowest response) and 46 per cent of those in the 35-49 age group agreed (the highest response). It is of interest that younger people appear to hold views similar to those of older people on free speech laws. However, some difference occurred when results were controlled for political affiliation.

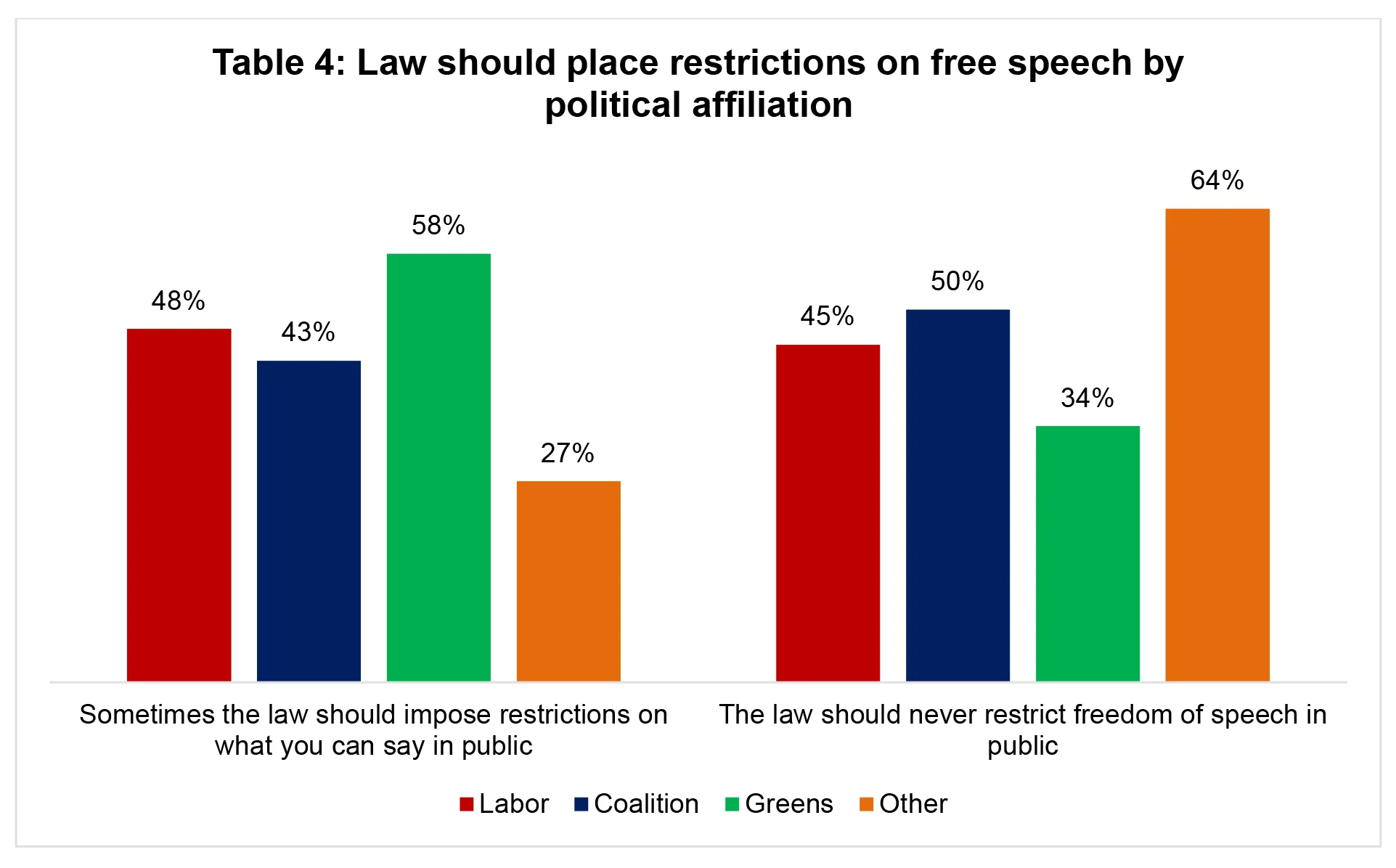

Whereas 48 per cent of ALP supporters and 43 per cent of Coalition supporters were in favour of some legal restriction on what can be said in public, this figure rose to 58 per cent for Greens supporters. Similarly, whereas 45 per cent of ALP supporters and 50 per cent of Coalition supporters thought the law should never restrict freedom of speech in public, only 34 per cent of Greens supporters thought so.

Nonetheless, even when controlled for political affiliation, there was a fairly equal distribution between those who favoured some legal controls and those who favoured none – although the proportion of those claiming ‘Other’ as their political affiliation favouring no restrictions on speech in public was much greater at 64 per cent. This might explain why successive attempts to reform section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 have succumbed notwithstanding the section’s dubious yet powerful prohibition against giving “offence”.[6] Laws constraining freedom of speech are supported by a sizeable segment of the Australian people and, once in place, appear to be considered indispensable for maintaining social cohesion and civility.

Political correctness

The term ‘political correctness’ refers to an anti-free speech movement that emerged on college campuses in the United States in the 1980s. Its aim was to challenge everyday use of language, both in the academy and beyond, in order to protect groups deemed vulnerable to sexism, racism and homophobia.

Offensive language came to be labelled as ‘hate speech’, a broad term deployed both to discredit dissenting views and to encourage self-censorship. Those who breach the protocols of political correctness run the risk of being ‘cancelled’ for their offence and can find themselves ostracised and vilified for their use of ‘hateful’ speech.[7]

Political correctness spread rapidly through, for the most part, English-speaking societies, such as Australia and the United Kingdom. It has been met with ridicule by some and acquiescence by others. Respondents in the YouGov poll were asked whether they considered “political correctness harmful or beneficial.”

Although 14 per cent of those surveyed were uncertain, a substantial proportion (44 per cent) thought that, on balance, “political correctness is mostly beneficial because it protects the rights of different groups.” Of this group, 48 per cent were women and 40 per cent men.

A slightly smaller number (42 per cent) considered political correctness “mostly harmful because it unfairly limits free speech.” In this group, the gap between the opinions of women and men was greater: 49 per cent of men considered political correctness mostly harmful as against 35 per cent of women. However, results also indicate that as both women and men get older, they are more likely to consider political correctness harmful.

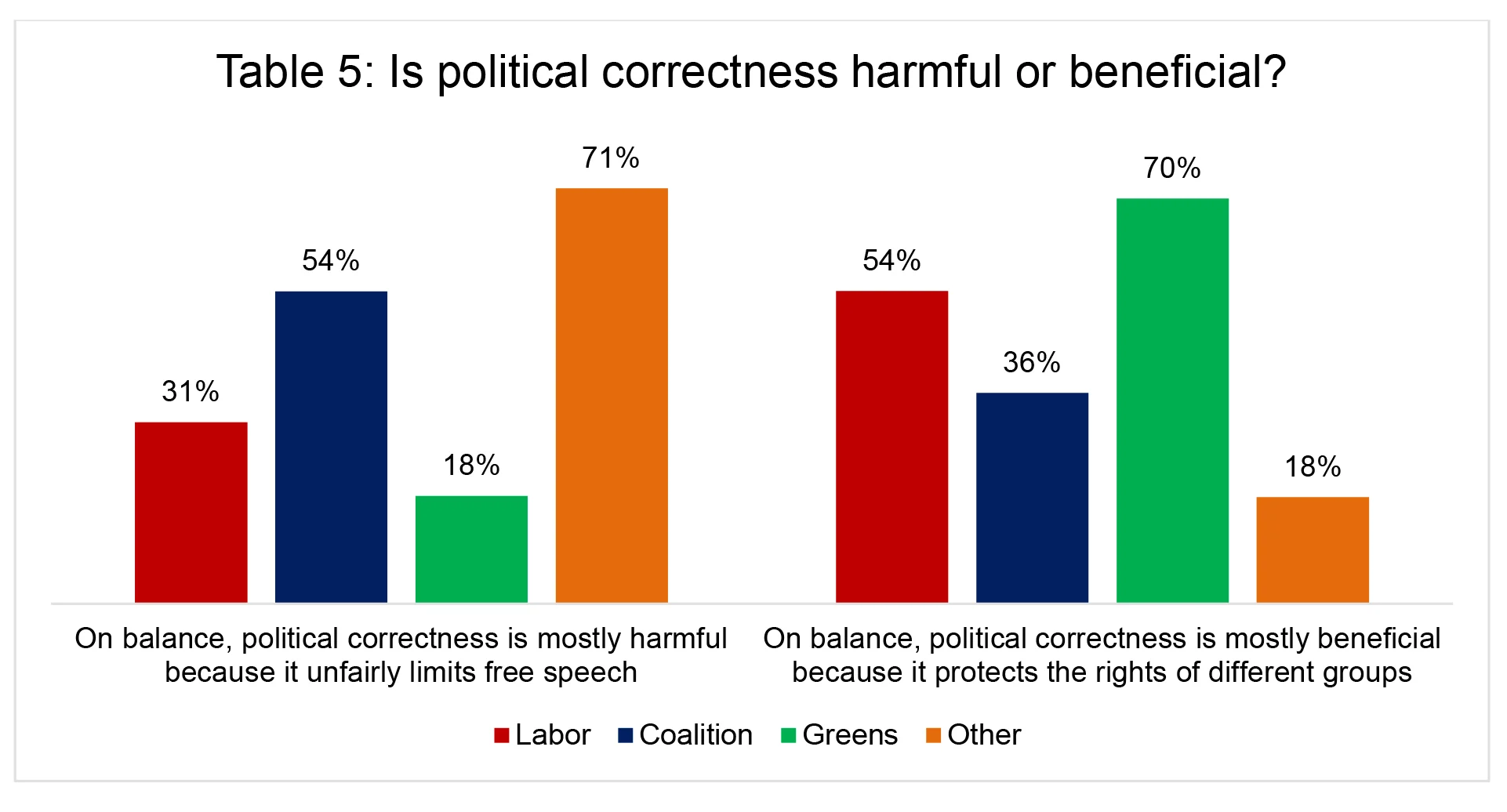

Opinion diverged more sharply when the results were controlled for political affiliation. Only a small percentage of Greens supporters (18 per cent) considered political correctness harmful, as against 54 per cent for Coalition supporters and 31 per cent for ALP supporters. Yet 70 per cent of Greens supporters considered political correctness beneficial, as against 36 per cent of Coalition supporters and 54 per cent of ALP supporters.

In other words, the further to the left one is on the political spectrum, and the younger one is, the more likely one is to consider political correctness beneficial. There is marked difference between the views of younger and older Australians: of those who considered political correctness beneficial, Gen Z was the largest group (56 per cent) followed by Millennials (50 per cent), Gen X (15 per cent) and Baby Boomers (12 per cent).

Younger Australians, attracted to positions on the political left — especially those advocated by the Greens — are far more likely to call for, and support, sanctions against those who breach the protocols of political correctness. Unless age and life experience ameliorate their views, we can expect the norms of political correctness and its concomitant, ‘cancel culture’, to remain influential in the Australian intellectual landscape.

Protecting religious freedom

Discrimination against individuals or groups on the basis of religion has been a vexed issue in Australia in recent years. Whether it has been about wearing religious vesture (such as the burka); running religious organisations (such as schools) according to the tenets of faith; or opposing social developments (such as same-sex marriage) for faith-based reasons, many who are affiliated to religious traditions claim to have been discriminated against on the basis of religion and that their religious liberty has thereby been infringed.

In particular, the debate about same-sex marriage between its proponents and those who opposed it for faith-based reasons became so vexed that the Morrison Government produced two exposure drafts of a religious discrimination bill. Both bills were intended to make it unlawful to discriminate against a person on the basis of their religious belief or religious activity. However, the bills failed to win parliamentary support and, with the defeat of the Morrison Government in May 2022, the issue was consigned to history.

However, advocates for legislation to protect religious freedom continue to argue that those who belong to a faith tradition face the threat of discriminatory behaviour on grounds of religious belief. The CIS/YouGov poll attempted to discover whether the issue of religious freedom remains an issue of concern and asked respondents about the extent to which “Australia protects religious freedom.”

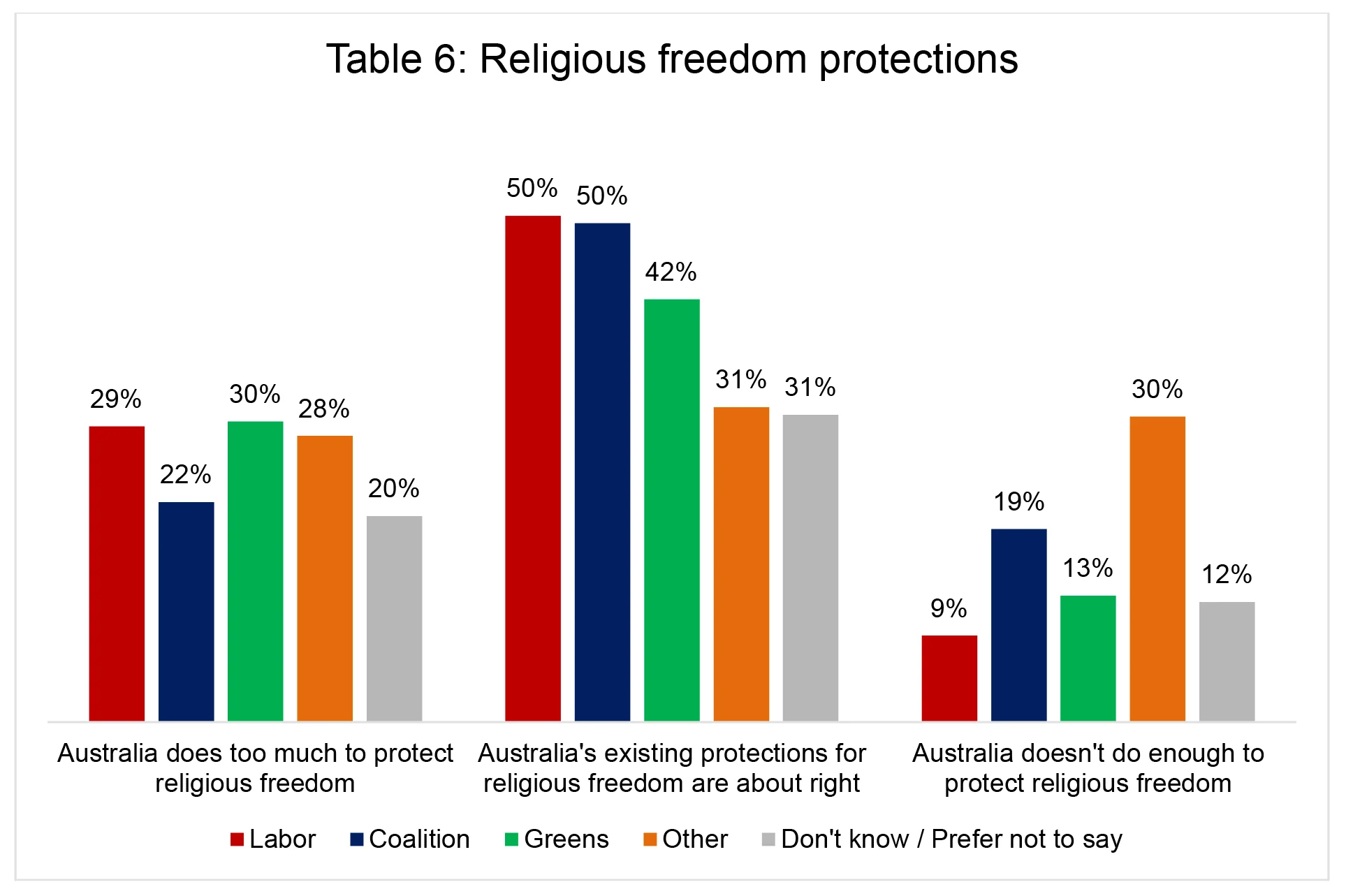

Nearly half (46 per cent) of those asked considered Australia’s protections for religious freedom to be “about right” and only 15 per cent thought Australia needed to do more. Just over a quarter of respondents (26 per cent) thought Australia already did too much to protect religious freedom.

Those with a religious affiliation (45 per cent of Protestants, 54 per cent of Catholics and 46 per cent affiliated to another religion) were more inclined to think Australia’s existing protections were adequate compared with 42 per cent of those who were not affiliated to any religion.

ALP and Coalition supporters (both on 50 per cent) thought current protections were about right as opposed to 41 per cent of Greens supporters. Greens supporters were also more likely to think Australia already afforded too much protection (30 per cent) as opposed to supporters of ALP (29 per cent) and the Coalition (22 per cent). Even when controlled for education level, age group and annual household income, differences in points of view were not great — although fewer with less than $20,000 annual household income (36 per cent) thought protections were about right than those in the $60,000-$69,000 income bracket (57 per cent).

On the basis of these findings, it is reasonable to conclude that the issue of protections for religious freedom is not nearly as pressing as it appears to have been two or three years ago. As economic and cost of living concerns mount in importance, it also seems reasonable to conclude that religious freedom protections are unlikely to be a priority for the Albanese Government.

The role of Christianity in Australia

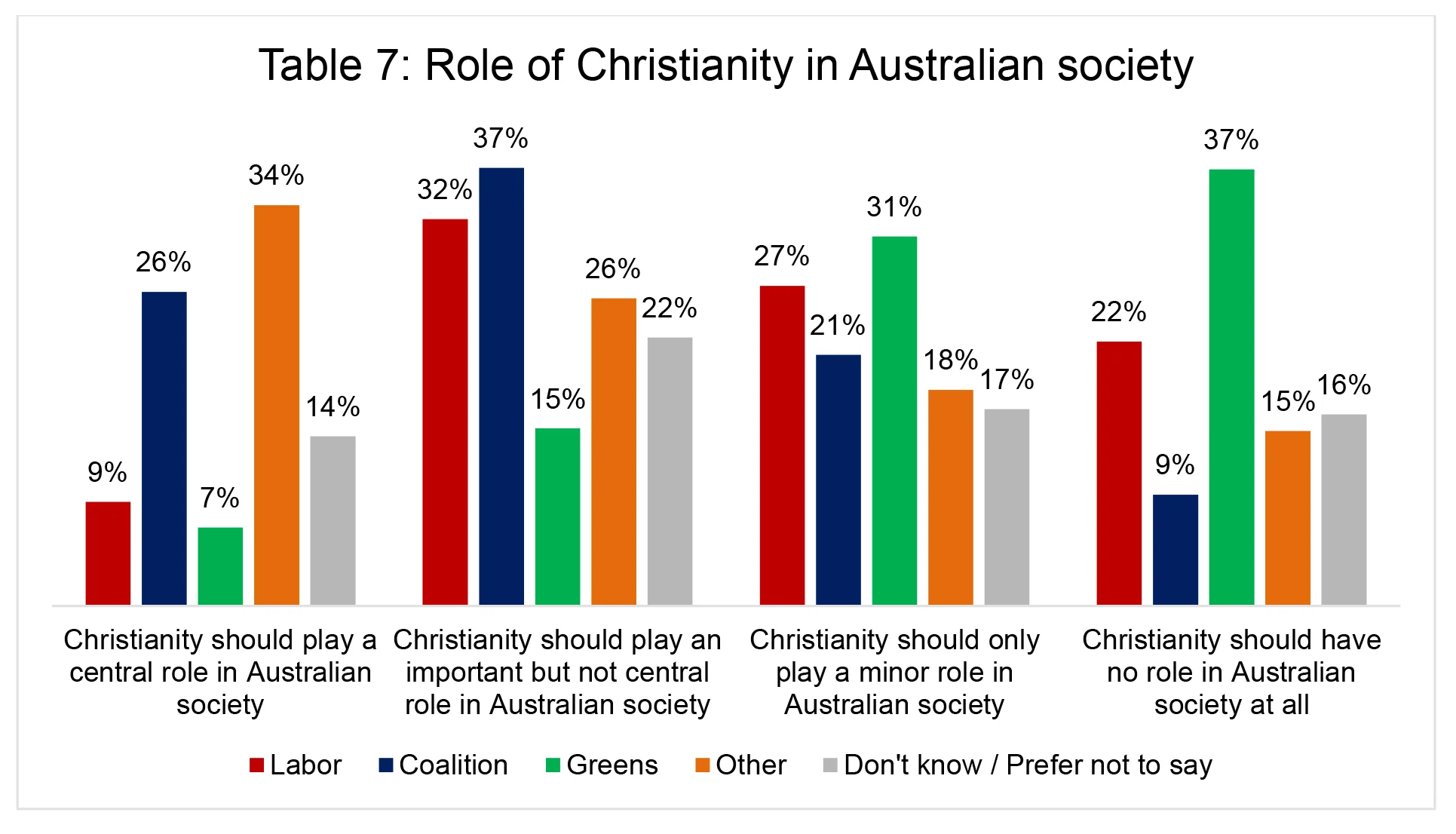

When asked specifically about “the role of Christianity in Australia”, respondents were evenly divided between those who thought Christianity should have a “central and important” role (47 per cent) and those who believed it should have a minor role or no role at all (42 per cent). The proportion of those strongly in favour of Christianity having a role in Australia (17 per cent) was comparable to those who strongly opposed it having any role (18 per cent).

However, when examined in terms of political allegiance, a different picture emerges (see Table 7). Coalition voters were much more strongly in favour of Christianity having a “central role” (26 per cent) than ALP voters (9 per cent) and Greens voters (just 7 per cent). However, the outlier here is the group of non-partisan respondents (34 per cent).

When respondents were asked whether Christianity should play an “important” role in Australia, the supporters of the two major parties were both comparable and both were high – Labor at 32 per cent and Coalition at 37 per cent, with non-party supporters at 26 per cent. Greens supporters (15 per cent) were again both different and negative towards Christianity.

Asked whether Christianity should have a minor role or no role at all, respondents who were Green supporters held the strongest views: 31 per cent thought it should have a minor role and 37 per cent thought it should have no role at all. This compares with 9 per cent of Coalition supporters who thought Christianity should have no role (compared to 22 per cent of ALP supporters). A slightly larger proportion of non-aligned respondents (15 per cent) thought it should have no role, a proportion comparable to responses from Greens supporters.

Clearly, Coalition voters and non-aligned voters are more supportive of Christianity than Labor voters, and far more so than the Greens — who are consistently out of sync with this view across the rest of the political spectrum. The broader question is whether Christianity has a place in the contemporary public square. Many — for example, 37 per cent of Greens supporters — think it should not. For the most part, however, our polling suggests that Australians are broadly supportive of the role Christianity plays in our society.

Staffing religious schools

Given the responses to Christianity in the previous section, one would expect a certain overlap regarding views as to whether religious schools should employ only those who share their values, and whether the respondents saw this issue as concerning all religious schools and not just Christian ones.

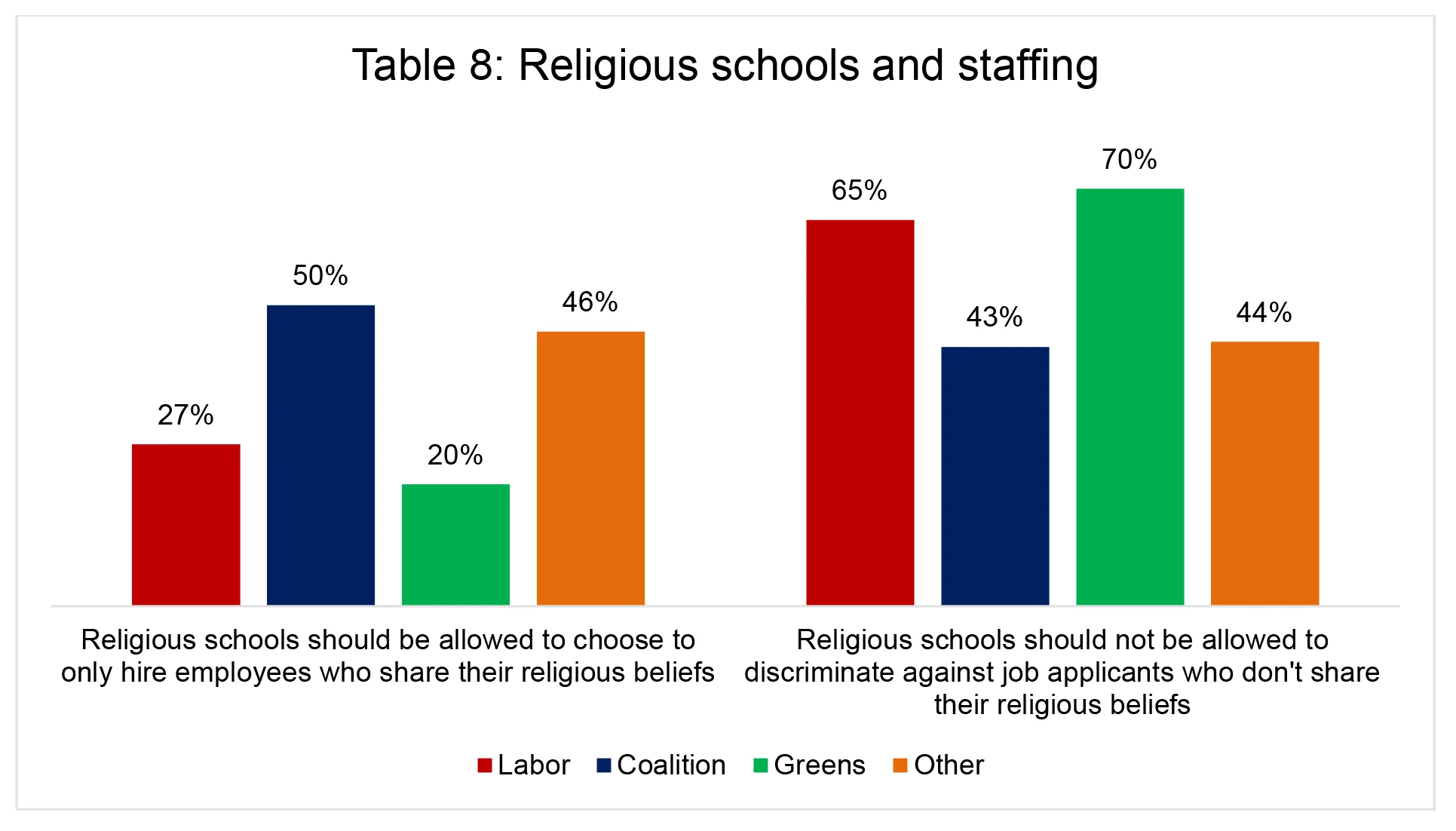

It should be noted that 34 per cent of school children currently attend non-government schools of which over 90 per cent are faith-based schools.[8] Just over one third of respondents (37 per cent) believe religious schools should be able to discriminate on the basis of faith about whom they employ, but a greater proportion (57 per cent) opposed this view and held that schools should not be able to discriminate in this way. The “don’t knows”, at 9 per cent, represented the smallest proportion of respondents.

This finding is significant and could well foreshadow wider political conflict between those demanding freedom of recruitment for faith-based schools (and other faith-based organisations) and those demanding strict compliance with anti-discrimination laws for all organisations. Although our polling results indicate the former is a minority opinion, it is, nonetheless, a sizeable minority whose viewpoint will count in political terms; particularly at elections as it has in the past.

Indeed, the large non-government school sector in Australia, with a third of all school students and with enrolment growth outpacing the government sector, has had from time to time considerable impact on government policy through its campaigning and lobbying efforts. Nor should it be forgotten that the considerable federal and state funding to the non-government school sector was largely based on the principle of giving parents ‘choice’ as to where to send their children.

In January 2023, an initial consultation paper published by the Australian Law Reform Commission proposed the erosion of the right of religious schools to preserve their religious character, standards and teaching. As noted by Dr Elisabeth Taylor, an independent Commonwealth scholar, in a new paper published by the Centre for Independent Studies, “religious schools would be forced to appoint staff who may not understand or support the school’s religious beliefs, and their employment could only be ended if they actively undermined the religious ethos of the school.”[9] At the time of writing (March 2023), it remains to be seen how the federal government will address the concerns of the ’37 per cent’ voiced about the ALRC paper and, in particular, the concerns of voters from Muslim and other non-Christian faith traditions.

On the first question, as to whether religious schools should be able to appoint whom they want, the views of Labor supporters and Greens supporters were comparable; at 27 per cent and 20 per cent respectively.

The outliers here are Coalition and non-aligned voters who are more strongly supportive of religious schools’ rights, at 50 per cent and 45 per cent, respectively. These are vastly different to the responses of Labor and Greens supporters. The difference between Coalition and Labor voters is greater on this issue compared to most others.

On the second question, as to whether religious schools should not be allowed to discriminate, responses from Labor supporters (65 per cent) and Greens supporters (70 per cent) are again very close but at odds with responses from Coalition supporters (43 per cent) and non-aligned voters (44 per cent) who appear to adopt a less interventionist approach.

The issue of religious tolerance is one of the few areas across all the issues canvassed by the survey where there is the closest congruence between Labor and Greens supporters. At the same time, responses from Coalition and non-aligned voters are strongly comparable. Significantly, the 44 per cent of those who responded as “don’t know” or “unwilling to say” is much larger than for any other issue canvassed.

What does all this indicate? Is Labor’s stance a reflection of their past support for free, compulsory and secular education; and now of its current opposition to funding the non-government sector especially religious schools? The Greens have long been opponents of non-government schools.

Even so, none of the questions in the survey place the matter in any religious context. Thus, the survey is inconclusive when it comes to assessing how this issue would play out in relation to Jewish and Muslim schools.

Religious discrimination in Australia

Even so, the findings of the CIS/YouGov poll indicate that Australians still think members of some faith groups — Islam, in particular — continue to experience moderate degrees of religious discrimination in Australia.

Respondents were asked about the extent to which they thought members of principal faith communities in Australia experienced discrimination. Whereas only 11 per cent thought Christians experienced “a great deal of discrimination”, 17 per cent thought Jews did and 35 per cent thought Muslims did. “Some discrimination” was thought to be experienced by Christians (21 per cent), Jews (36 per cent) and Muslims (35 per cent). The total experience of discrimination thought to be borne by Muslims was far higher (82 per cent) than for Christians (61 per cent) or for Jews (74 per cent).

Even when controlled for educational attainment, age group and annual household income, the level of religious discrimination thought likely to be experienced by Muslims was consistently higher than that for Christians or Jews.

Larger differences were evident when the data was controlled for political affiliation. Whereas 38 per cent of ALP supporters and 28 per cent of Coalition supporters thought Muslims were likely to experience religious discrimination, this view was held by 60 per cent of Greens supporters. Yet Greens supporters appear to consider lower levels of discrimination to be experienced by Jews (16 per cent) or Christians (4 per cent).

Sensitivity to controversy

Overview

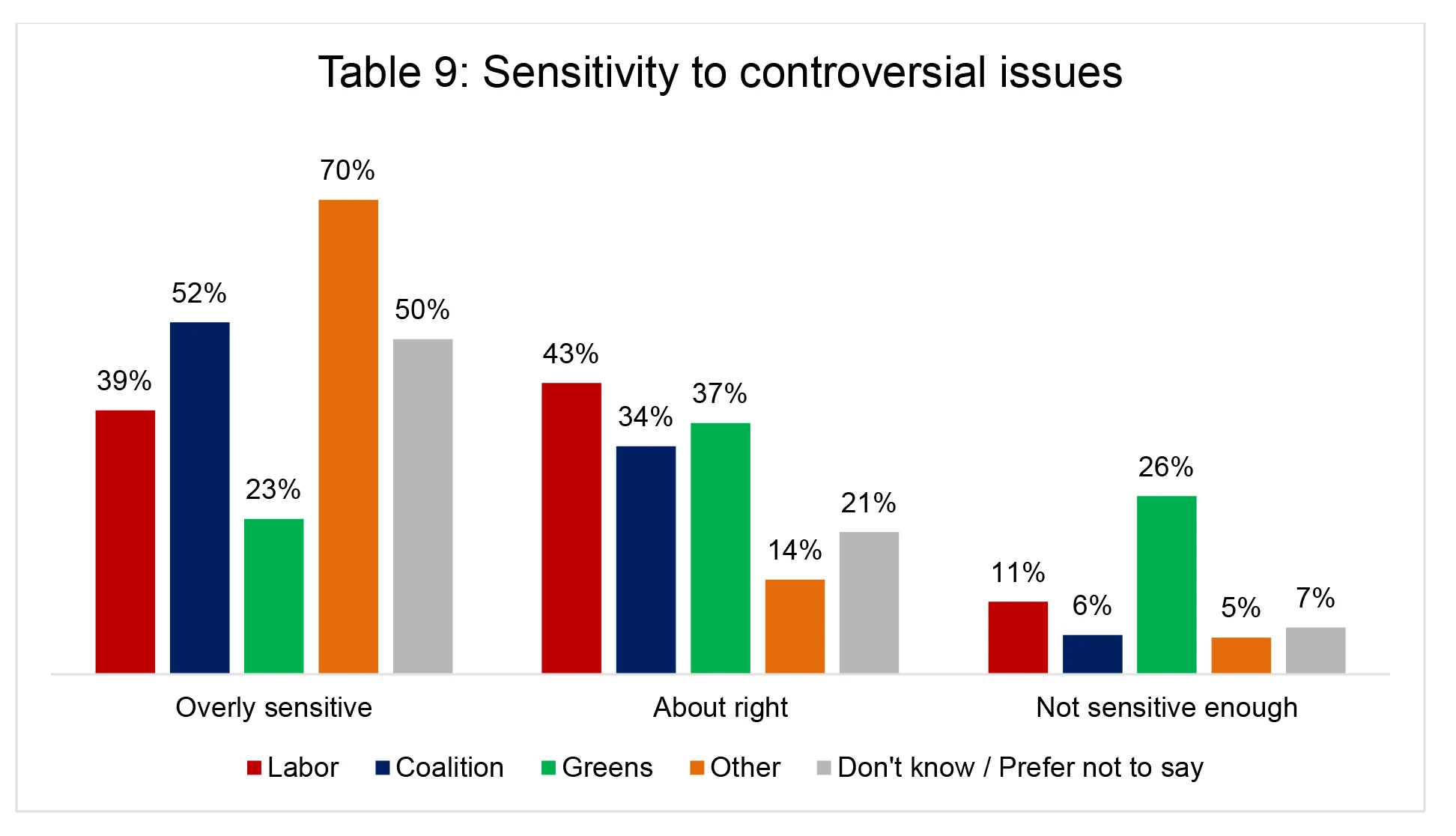

Respondents were asked how sensitive they thought Australian society was to controversial opinion. The first question just asks whether Australian society is “over-sensitive” to “controversial opinions” – although what amounts to “over-sensitive” or “controversial” was left to each respondent to define for themselves. Overall, a sizeable 45 per cent of respondents thought Australian society is overly sensitive and 35 per cent thought it was about right. Only 10 per cent thought we were not sensitive enough. So, while not completely even, the assessment suggests there is an issue here.

However, responses by political affiliation give a very different complexion to this matter and here we see some of the biggest disparities in the survey between supporters of the major parties: the Coalition (and non-aligned voters), Labor and the Greens.

52 per cent Coalition voters and 70 per cent of non-aligned voters consider that Australia is “overly sensitive”. This contrasts with 39 per cent of Labor supporters and 23 per cent of Greens supporters. Labor voters are allied closely to Greens on this issue.

In summary, there is some real concern about sensitivity across the major party blocks, but the greatest concern is among Coalition voters and non-aligned voters. The large number of “don’t knows” (50 per cent) perhaps reflects the ambiguity of the topic.

Countering this response is the proportion of respondents who considered Australian sensitivity to controversial opinions to be “about right” (35 per cent). This compares favourably with responses to the question of political correctness that on balance it was “beneficial” at 44 per cent; and those who judged religious protections “about right” – 46 per cent.

Here on “about right” there was far more comparability across the parties — 43 per cent Labor, 34 per cent Coalition, and Greens 37 per cent — but non-aligned voters were not convinced with only 14 per cent thinking it was “about right”, which fits with their 70 per cent concerns mentioned above.

When it comes to the view that Australia is not sensitive enough to controversial opinions, few held this view among Coalition supporters (6 per cent). This compares with responses from Labor supporters (11 per cent) and non-aligned voters (5 per cent) who thought we were not sensitive enough. However, this is way below the response from supporters of the Greens (25 per cent) who see the need for more sensitivity — but this is not a big result compared to the other responses from Greens supporters.

Policy and political implications for freedom of speech

What does all this mean? Any assessment needs to consider both the policy and the political implications of the responses. These are intertwined. If an issue becomes ‘political’ — that is, controversial and marked by disagreement, partisanship and a possible vote winner or loser — it will drive policy to show concern, secure advantage and or solve or reduce the problem. Similarly, no policy solution (regardless of how evidence-based) will avoid producing political impacts that have to be managed or accommodated.

How ‘political’ an issue is will affect whether an issue gets on the agenda for possible government action as well as what policy might be proposed, and over what timeframe. It will also be influenced by whether a party is in office, the electoral cycle (for example, proximity to the next election), party ideology, values and history, polling and its ‘do-ability’ (constitutionality, costs, and administrative ease).

Moreover, it must be appreciated that many issues have different meanings and importance for different groups depending on their values, roles and positions. Issues like ‘freedom’, for instance, can mean many different things.

There are two aspects in considering the policy and political implication of this survey:

- Does the survey indicate there is a problem and thus warrants some sort of government/public policy response? In other words, is freedom of speech an issue warranting recognition, definition and action, or is it just a ‘beat up’ by some commentators? How this is interpreted depends on how freedom of speech is seen — an open slather or with some restrictions. It is the latter that causes problems in developing policy as when, on what criteria, and by whom should restrictions be applied?

- If assessed as some sort of problem, it is important to review that through the partisan prism — Coalition, Labor, Greens — given their importance in driving policy and politics in Australia. The non-aligned voters are included here where relevant as they are seen as a significant group in their own right (more about them later). How different partisan groups/voters see issues affects how the politics are played and the policy adopted.

Is there a policy problem?

All policy is based on the premise that there is a ‘problem’ needing to be addressed and requiring some government action. The nature and extent of the ‘problem’ and hence possible responses to it, are open to definition from a wide range of perspectives.

Overall, responses across several categories combine to suggest there is enough weight to conclude that in Australia freedom of expression/speech is a policy — and thus political —problem.

- QA1 concerning freedom to express opinion across work, family and friends highlights this.

There is overwhelming support that there is freedom to express what people think with family and friends (87 per cent and 84 per cent) where potential government intervention would be limited anyway if it weren’t.

More importantly, that only 44 per cent thought they were free at work is a different and smaller proportion than from the home and friends results. This, and that 28 per cent did not feel free overall, makes freedom of expression a policy problem. It can become a public policy problem because work is an area where government can legitimately exercise some intervention (eg: industrial relations, workplace anti-discrimination laws). Politically, it is an issue because of the large number of the responders who expressed concern about this matter.

In terms of politics the large 44 per cent concern about freedom of expression at work would be seen as a signal that all is not well in the workplace. It would be seen by Coalition parties as a reflection of:

- too much ‘political correctness’ (see later) and firms taking stands on ‘political’ issues e.g. referendum/climate change they never used to — and, responders may argue, never should;

- it would reinforce their views of the ‘silent majority’ who are against such roles by corporations;

- it could reinforce their natural policy inclination to be wary of such ‘faddish’ behaviour.

The issue would be: what might the Coalition propose to respond to this concern — regulation, exhortation, or just public expression?

The market gap here is that there has been no criticism from the parties about these trends at work; it may just be a public expression of concern is all that is needed.

For Labor, it is that these results signal concern (and votes) that the mantra and restrictions at work may be going too far.

- QA2 should law restrict what can be said in public. 47 per cent thought there should be no legal restrictions compared to 44 per cent who thought there should.

Although relatively even, that such a large proportion thought restrictions should not be imposed is politically significant and a warning against further intrusive government regulation in this area. However, given that a sizeable 44 per cent of those surveyed supported legal restrictions means that there may be some political opportunity here for some political parties. Accordingly, this split makes it a ‘political’ issue and poses a problem for governments to resolve.

This suggests the status quo should prevail and that government does not seek to define ‘political correctness’ and adopt a less interventionist approach to enforce particular compliance. The problem is that the ambit of ‘political correctness’ issues appears to be ever-widening; which governments and other social institutions too easily accommodate by some form of intervention regardless of how small the minority group who is making the complaint. To just maintain the status quo requires a certain degree of resisting or rejecting the complaint — of drawing a policy ‘line in the sand’ reflecting clear principles.

Politically, the 44 per cent in favour of some laws controlling speech in public aligns closely across both Coalition (43 per cent) and Labor (48 per cent) voters — but these are lower than the Greens (58 per cent), and the non-aligned who are below all of these at 28 per cent indicating even less enthusiasm for laws in this area.

However, this response needs to be read in conjunction with the next question as to “never restrict freedom of speech in public” for which responses from Coalition (50 per cent) and Labor (45 per cent) are again close; and as before, Greens (34 per cent) and non-aligned at the higher 64 per cent.

Coalition voters clearly want some protections but given their high (50 per cent) desiring of no restrictions they are not only distinguishable from Greens but more importantly there is clearly an untapped non-aligned level of support which could be tapped. Indeed, this group could be part of non-Labor’s “lost base”?

For Labor, the poll shows results distinctive from one of their prime rivals — the Greens. Overall, it is possible to foresee the different political responses: not push too hard on imposing sanctions on freedom of speech (Labor and Greens); and to defend more and make a statement of principle as this would confirm their bases (Coalition).

- QA3b on whether ‘political correctness’ is beneficial or harmful highlights the same issues as discussed in relation to QA2 above; though slightly in reverse, with 44 per cent saying it is “mostly beneficial” and again a sizeable group, 42 per cent disagreeing. The vagueness of what ‘political correctness’ means (different from straight freedom of expression above) would make this an even more difficult challenge for governments to settle politically. Further, what could realistically be a policy response to this issue? Governments (or someone) would have to identify what areas, policies, practices, utterances constituted ‘political correctness’ — itself a very value-laden process — and then consider how they might address these issues. How this might be played out in political and policy terms will depend on how this is seen through different partisan eyes.

However, in terms of political affiliation, different interpretations can be made with greater division between the Coalition and Labor rankings and between Labor and the Greens (Table 5).

Some 54 per cent of Coalition respondents believe political correctness is harmful compared to 31 per cent Labor and only 18 per cent for Greens. Again note that 71 per cent non-aligned believe it is harmful.

Coalition voters polled lower on the next question (ie beneficial to protect different groups), with 36 per cent believing political correctness is beneficial, compared to Labor’s 54 per cent and Greens’ 70 per cent. Note again that non-aligned voters were also lower at 18 per cent — suggesting this is a potential area for both the Coalition and Labor to exploit.

For Labor, the issue is the disparity with the Greens: 54 per cent vs 70 per cent on the beneficial nature of political correctness.

- QA4 Australian protection of religious freedom shows 46 per cent believe there are adequate protections, compared to only 26 per cent who think there is too much, and only 15 per cent who consider there is too little. Thus, the policy/political lesson here is that no further government action is needed but to keep some limited safeguards in place.

In terms of partisanship, there is considerable comparability across the political spectrum (see Table 6) — all are giving a moderate response ‘not too much’ — with Coalition a little more sceptical.

However, the question on whether protections are “about right” is also very high between the major Labor and Coalition parties, equal at 50 per cent with the Greens not too far behind at 42 per cent. The non-aligned voters at 31 per cent are less sure.

In the consideration of “doesn’t do enough to protect religious freedom”, the major parties are at the lower end of scale; with Labor voters at 9 per cent and Coalition supporters 19 per cent — in other words, there is no great demand from these voters for more government protection. Greens are at 13 per cent. The outlier here are non-aligned voters at 30 per cent. Politically, more protection of religious freedom is not seen as a big issue. The message to parties should be to leave well alone, given the complexities of developing policy in this area which might produce counter results to what some might want — such as religious protection.

- QA5 Role of Christianity in Australian society

There is another almost even split with 48 per cent seeing Christianity as having an important role, compared to 42 per cent seeing it having a minor role (18 per cent seeing no role). Whether this is an issue really depends on individual assessment.

However, when considered across partisan divide the results are more illuminating (see Table 7). Here, major differences between Coalition (and non-aligned voters) and Labor and Greens are clearly observable.

Coalition voters on central (26 per cent) and major roles (36 per cent) were similar to non-aligned voters (34 per cent and 26 per cent) — while Labor is at 9 per cent on central roles but closer to the Coalition at 32 per cent for major roles.

This time, the outlier is the Greens, who have the lowest scores on supportive roles of Christianity and the highest score advocating no role (37 per cent) while Labor is at 22 per cent, and the Coalition has the lowest result here at 9 per cent.

Given this result, Coalition leaders need to recognise that Christianity underpins much of its supporters’ beliefs, and that is supplemented by the non-aligned voters. In a secular society, this is a difficult path to tread.

For Labor leaders there is still a residue of support for Christianity exerting an important role in society, and again this is in contrast to the Greens — suggesting Labor should be careful regarding this.

- QA8 on sensitivity to controversial views reveals all is not well, with 45 per cent responding that we are “over-sensitive” compared to 35 per cent who saw the right amount of sensitivity. This seems slightly at odds with responses on political correctness (or at least how that term is being interpreted). Nevertheless, 45 per cent being the concerned/alarmed group makes this a political issue — it is an expression of concern that Australia has become too sensitive on too many issues, compared to the more ‘laid back’ culture Australians once cultivated and were known for previously.

What these results show, as in many areas covering social values and issues, is that the public opinion responses are never clear cut, often ambiguous and sometimes, as noted above, contradictory. This makes it difficult for governments and political parties to know how best to respond in both policy and political terms. The meaning in concrete policy terms is unclear except perhaps as a warning to leaders across all organisations to stop genuflecting to every latest alleged aggrieved group. After all, controversial views can often be the forerunner of breakthrough genuine reforms. It is the partisan lens that will make hay with this issue.

Further partisan differences were revealed here (see Table 9) with Coalition (50 per cent) and non-aligned (70 per cent) saying we are too sensitive. Labor is 39 per cent and Greens again different at a lowly 23 per cent. The “don’t knows” at 50 per cent is very high on this question and is therefore worth mentioning. So, politically this is an issue Coalition parties might pursue, especially given the high response rate from non-aligned voters — there is real concern out there, it seems. Labor also needs to pull back a little in being too condemnatory of some expressions.

While there is general agreement that we are not lacking sensitivity and do not need to be more sensitive — with Coalition, Labor and non-aligned similar (6 per cent, 11 per cent, and 5 per cent) — the Greens are the outlier again here with a higher dissatisfaction rate (23 per cent) seeing a need for more sensitivity.

Conclusions

Overall, the survey supports the contention that constraints on freedom of speech in Australia are an issue. It cuts across work situations, levels of government regulation and attitudes to religion. It is an issue of concern, but not a ‘crisis’ with a need for heavy corrective action by government.

In political terms, there is potential for those who can develop a cohesive narrative to gain considerable political capital out of supporting greater freedom of speech, but not in an aggressive free-for-all fashion. It might be linked to Australia’s once more ‘laid-back’ approach, calling a ‘spade a spade’, tolerance, pragmatism and our sense of egalitarianism and fairness.

In relation to policy, it is less clear what the actual government initiatives might be. So many factors in this policy space are not determined by legislation or punitive regulation but by attitudes and practice in everyday life.

However, as the next section suggests, such is not the case in partisan politics and policy where scoring points, collecting votes, and first mover advantage, are the order of the day.

In summary the key findings of this survey are:

- Freedom of speech is an important issue overall, as there is a sizeable proportion of voters who rank it as being very important;

- Importantly, many of these concerns are interpreting freedom of speech in terms of restricting people’s abilities to say what they think, wherever they want;

- However, there is not a ‘crisis’ – yet;

- In policy terms, it is not clear what specific actions governments should take, or that much can be achieved by legislation that might create another set of problems rather produce any benefits;

- Much can be achieved in policy less by specific legislation or regulation and more by clear statements of principles. This is an area where this has been lacking;

- Politically, there is more congruence between the Labor and Coalition parties than between Labor and the Greens;

- Importantly, non-aligned voters express more concerns and tend to be more aligned to Coalition voter concerns about restrictions on freedom than to Labor supporters. Non-aligned voters have little in common with the Greens. This indicates there are considerable votes for those who can enunciate clear views about protecting freedom of speech and resisting political correctness and regulation;

- The Greens are generally out of sync with everyone; so Labor needs to appreciate that in driving their policy orientation to head off a loss of voters to the Greens, they have the potential to lose votes;

- The Coalition parties need to assess where this survey (and the responses from non-aligned voters) reflects their base and traditional philosophy and should respond accordingly;

- Labor needs to understand that their move to accommodate the Greens is making them an extremist leftist party — the opposite to the Whitlam reforms.

- The Greens’ agenda risks them being labelled as extremists.

Endnotes

[1] “A $44bn education”, The Economist, (24 December 2022) Elon Musk’s $44bn education on free speech | The Economist

[2] Ashleigh Barraclough and Judd Boaz, “New Essendon CEO Andrew Thorburn steps down”, ABC News, (4 October 2022) New Essendon CEO Andrew Thorburn steps down – ABC News.

[3] Stan Grant, “Essendon, Andrew Thorburn and Christianity: The battle of values that cost a man his job”, ABC News, (9 October 2022) Essendon, Andrew Thorburn and Christianity: The battle of values that cost a man his job – ABC News

[4] Monica Wilkie and Robert Forsyth, Respect and Division: How Australians View Religion, (Centre for Independent Studies: Sydney NSW, 2019), 3.

[5] Monica Wilkie and Robert Forsyth, as above.

[6] Section 18C Racial Discrimination Act 1975 states: “(1) It is unlawful for a person to do an act, otherwise than in private, if: (a) the act is reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person or a group of people; and (b) the act is done because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of the other person or of some or all of the people in the group.” See further, Peter Kurti, The Tyranny of Tolerance: Threats to Religious Liberty in Australia, (Connor Court: Redland Bay QLD, 2017), 28.

[7] See further, Peter Kurti, Cancelled! How ideological cleansing threatens Australia, (Centre for Independent Studies: Sydney, 2020).

[8] It is worth noting that a greater proportion of students (50 per cent) attend secondary non-government schools in capital cities.

[9] Elisabeth Taylor, How Adequate are Australia’s Protections for Religious Freedom?, (Centre for Independent Studies: Sydney, 2023, forthcoming).