Executive Summary

- Government overreach: The federal government’s planned $78 billion of off-budget measures over the next four years reflects an increasingly common phenomena of governments wanting to intervene across the economy using all available means. Much of it is activist industrial policy, wanting to reshape the economy. Some of it is blatant vote buying, such as the recently announced 20% HELP debt write-off.

- Impact on budget transparency: Partly, off-budget measures reflect a desire to obscure the budget impact of government activities. Off-budget measures can obscure the true financial position of the government, reducing transparency and accountability, especially as information is often shielded under claims of commercial-in-confidence.

- Risks to balance sheets: These activities can increase risks to government finances due to the potential for underperforming investments, write-offs, or bad debts. The Federal government already writes off around one dollar in every six lent out as HELP. Furthermore, off-budget activities create long-term fiscal risks through contingent liabilities that are not fully appreciated by governments.

- Economic consequences: Off-budget spending contributes to higher debt and interest payments, potentially leading to higher taxes, which can reduce productivity and living standards. It also may exacerbate inflation.

- High opportunity costs: Government financing vehicles like the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) and National Reconstruction Fund Corporation (NRFC) are increasingly used to meet policy goals (e.g. climate policy and industrial policy) but can lead to inefficient use of resources and underperforming investments.

- Concerns about legitimacy: Many off-budget activities lack a clear market failure justification. Activist industrial policy measures undertaken off-budget risk picking losers rather than winners.

- Recommendations: include better reporting and transparency of off-budget activities, quantification of fiscal risks, and more rigorous oversight of government investments and their economic implications.

Introduction

Off-budget activities in entities such as the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) and Snowy Hydro are being used to advance policy objectives. In some cases, politicians exploit budget accounting rules to achieve policy objectives while minimising the impact on the budget metrics typically watched by commentators. In other cases, off-budget activities are a reflection of mixed economies, where governments attempt to achieve policy objectives through various means, as the lines between private and public sectors are blurred.[1] Overall, off-budget activities expand the reach of government, are bad for transparency, add new risks to government balance sheets, and ultimately can result in lower productivity and living standards.

The 2024-25 federal budget included $78 billion in net cash outflows in the cash flow line item “net cash flows from investments in financial assets for policy purposes” over 2024-25 to 2027-28.[2] These funds represent lending activities of government investment vehicles, or equity injections or lending to government-owned businesses for policy-related activities. State governments also engage in substantial off-budget activities. These measures do not directly impact the budget’s underlying cash balance — the ‘bottom line’ focused on by the commentators — although they affect the headline cash balance. They also indirectly affect the underlying budget balance to the extent that the cost of financing them — public debt interest — is not fully offset by income (i.e. interest and dividend income) generated by these activities, which is often the case. These activities come at substantial opportunity costs, which are not obvious from their budget treatment.

The volume of these cash flows is expected to stay substantial or increase in future years. The Productivity Commission has observed that concessional finance by governments, a substantial part of the net cash flows in question, is a growing category of industry assistance.[3]

Governments are increasingly undertaking off-budget activities that involve movements on their balance sheets that do not directly affect their budget bottom lines. Australian governments are resorting to so-called ‘off-budget’ measures to improve the appearance, but not the reality, of their financial positions. The federal government’s November 2024 announcement that it would reduce Higher Education Loan Program (HELP) debt by 20% is a good example of this trend.[4]

This can be bad for transparency and accountability, and brings risks to government balance sheets, as this paper outlines. Furthermore, it means the government’s effective spending is higher than otherwise, potentially contributing to inflation. Previous CIS research has highlighted the link between government spending and inflation; and off-budget spending only makes the problem worse.[5]

This paper first explores what off-budget spending means. It then examines the extent of federal and state government off-budget spending, and subsequently discusses the policy implications.

To listen to this research on the go, subscribe on your favourite platform: Apple, Spotify, Amazon, iHeartRadio or PlayerFM.

What do we mean by off-budget?

To understand what is referred to as off-budget spending, we need to first understand how budgets are presented in the Uniform Presentation Framework (UPF) adopted by the federal, state and territory governments. This is broadly consistent with the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) Government Finance Statistics (GFS) framework.

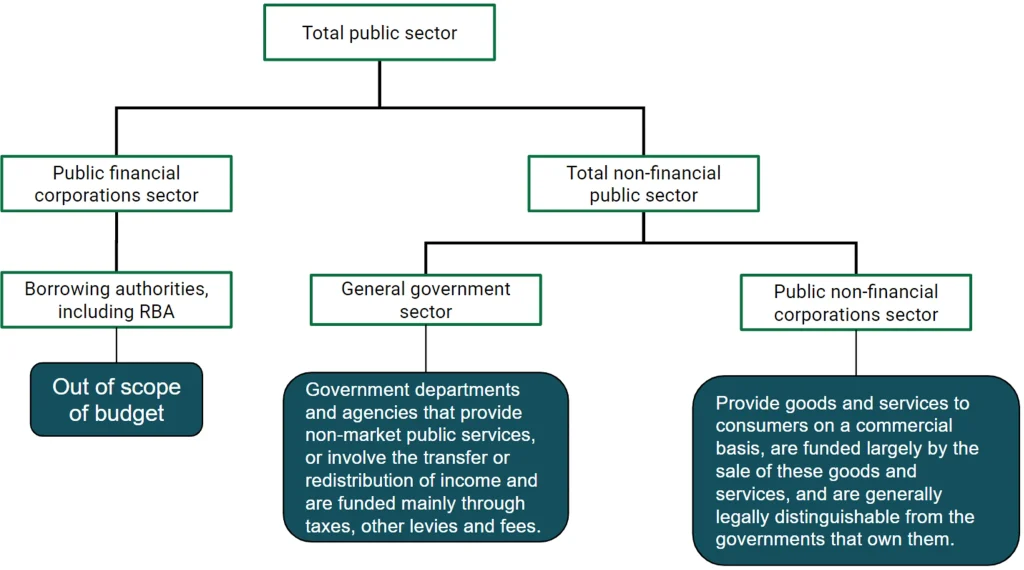

At budget time, the focus is on the budget balance for the general government sector, which comprises government agencies such as health, education, and treasury but excludes government-owned corporations (GOCs) operating commercially. The UPF distinguishes between public non-financial corporations (PNFCs), which deliver goods and services (e.g., energy businesses, ports, and railways), and public financial corporations (PFCs), which deliver financial services, such as banking (Figure 1). Under the UPF, budget documents provide financial information (i.e. operating statements, cash flow statements, and balance sheets for the general government and PNFC sector, but not for the PFC sector.

Figure 1. Breakdown of the public sector in UPF

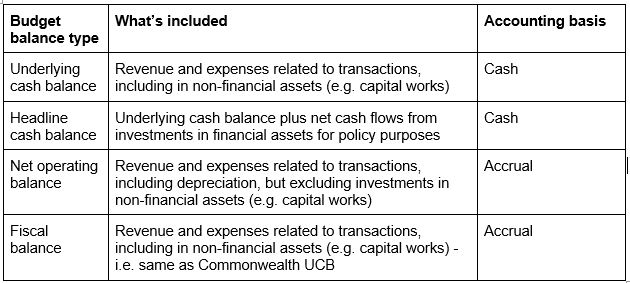

The underlying cash balance (UCB) is the important budget balance for the Commonwealth. For the states, generally, the focus is on the net operating balance, which includes depreciation but not net capital purchases.[6] These budget balances cover transactions and investments in non-financial assets such as roads, bridges, and buildings (Table 1). They exclude investments in financial assets.

Table 1. Budget balances

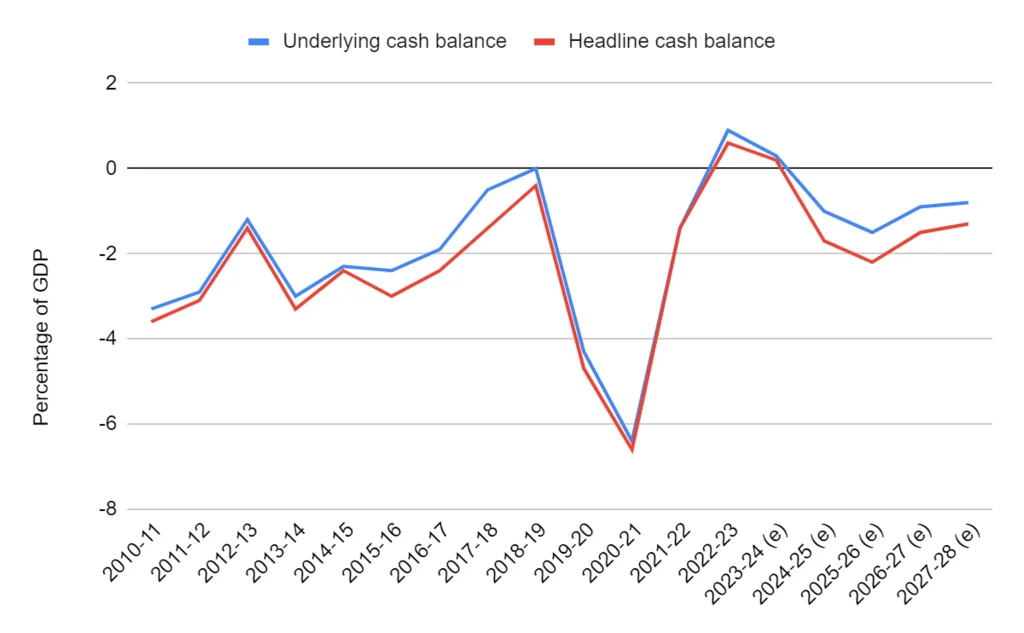

For the federal government, the off-budget activities discussed in this paper lead to significant divergence between underlying cash and headline cash balances (Figure 2). In some years, the gap is small, and it widens significantly when the federal government makes significant loans or equity injections to off-budget entities; including PNFCs such as National Broadband Network (NBN) and Snowy Hydro and investment vehicles like the CEFC and National Reconstruction Fund Corporation (NRFC). While the CEFC and NRFC are within the General Government Sector, and their operational costs are accounted for in the budget bottom line, their financing activities are ‘off-budget.’[7] Furthermore, the general government may invest in Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) such as WestConnex.

Figure 2. Underlying cash and headline cash balances, Australian Government

Source: Australian Government Budget 2024-25.

How budgets and budget balances are constructed and presented suggests various opportunities for politicians to seek a more favourable budget treatment. They may try to push non-commercial general government activities into the PNFC or PFC sector, in which case outlays associated with them do not directly or fully impact the budget balance or debt figures. The NBN was arguably a good illustration of this. As ABC business editor Ian Verrender has observed: “To keep the NBN “off the books” and not part of the federal budget, the Rudd government classified the project as an “investment” rather than just government spending.”[8]

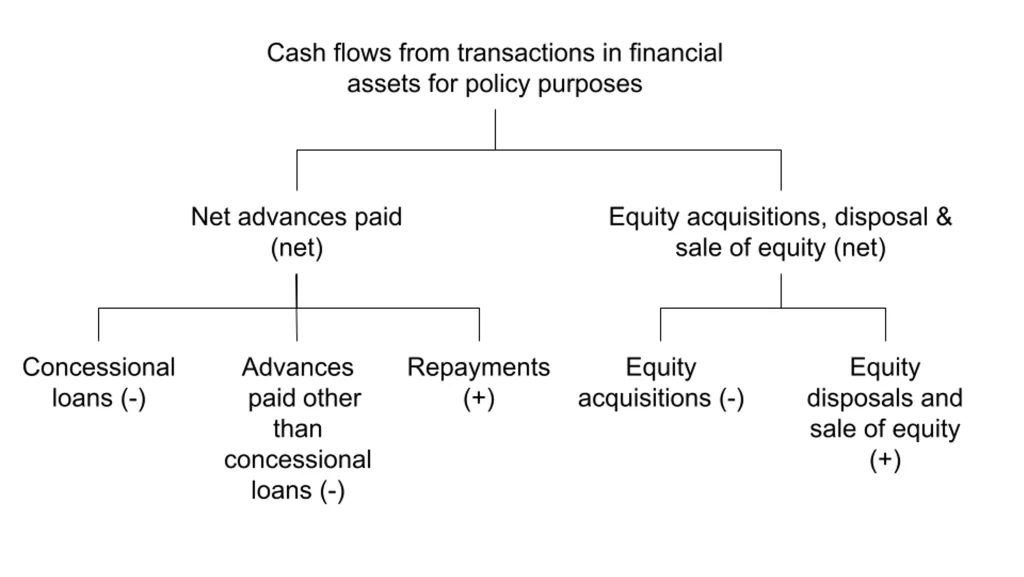

The types of off-budget transactions are set out in Figure 3. This category includes various types of concessional loans (offset by repayments) or purchases or sales of equities in private and public sector businesses. As we will see, changes in the total net cash flows can be due to any of these. At times, privatisation proceeds have dominated. At other times, investments in government-owned businesses or, conversely, equity extractions (e.g. via special dividends paid by PNFCs) have dominated. That is, net cash flows from investments in financial assets for policy purposes need not be negative. For example, the Queensland government experienced a $3.4 billion positive net cash flow from this item due to drawing a large special dividend from energy businesses. Incidentally, this came about through creative accounting. The government directed the energy businesses to borrow billions of dollars so the government could extract the funds and use them to pay down general government debt, bringing about a reallocation of debt from the general government to the PNFC sector.[9]

Figure 3. Breakdown of net cash flows from transactions in financial assets for policy purposes

Source: Based on ABS (2015).

Note: the + and – signs in the brackets on the final row denote whether the item is a positive or negative cash flow for the government.

For simplicity, this paper refers to negative cash flows for policy purposes as off-budget spending, even though the transactions are more precisely referred to as loans or equity injections, et cetera.

What has the Commonwealth been doing?

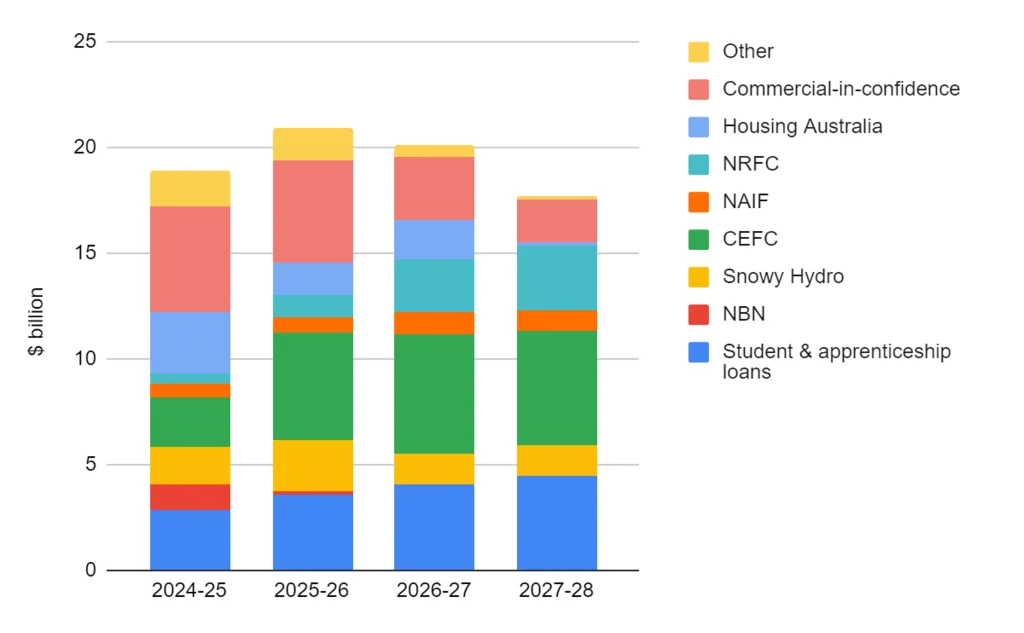

The Treasurer is pulling all the levers of government at his disposal to achieve the government’s mission of rapidly moving the economy toward net zero greenhouse gas emissions. The budget includes billions of tax incentives for so-called ‘green hydrogen’ and critical minerals development. It also includes tens of billions of ‘off-budget’ funding, revealed in the net investment in financial assets for policy purposes line item of the cash flow statement (Figure 4). This off-budget funding does not directly or fully impact the federal government’s underlying cash balance or state government budget balances and, hence, can be controversial.

Figure 4. Net investments in financial assets for policy purposes, by type, Australian Government

Source: Australian Government 2024-25 Budget Paper no. 1, p. 102.

This off-budget funding, among other destinations, goes to government financial corporations that make loans to finance various projects consistent with the government’s policy objectives. For example, $19 billion is available for the CEFC to make loans under the Rewiring the Nation policy. Other financing organisations include the NRFC, which aims to “to diversify and transform Australia’s industry and economy”, and the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (NAIF), which has a vision “to transform northern Australia through financing infrastructure development”.[10]

The investments in financial assets for policy purposes include any loans to, or equity injections into, government-owned corporations such as Snowy Hydro — which is receiving $4.5 billion in loans and around $2.9 billion in equity injections over 2023-24 to 2027-28 (see Budget Paper no. 1, Table 3.4, p. 102). Additionally, there would be any deposits the government makes into various policy funds, such as the Housing Australia Future Fund.

The heavy use of off-budget funding illustrates the current federal government’s extensive policy agenda regarding the transition to net zero, among other priorities. In its last budget, the previous federal government planned smaller — though still significant — investments in financial assets for policy purposes, an annual average of $8.4 billion over 2022-23 to 2024-26, compared with the current government’s annual average of $19.4 billion over 2024-25 to 2027-28. This compares with the average annual total federal payments (excluding investments in financial assets for policy purposes) of $775 billion over this period. That is, off-budget activities imply 2.5% more government activity than is suggested by the total payments figures in the budget.

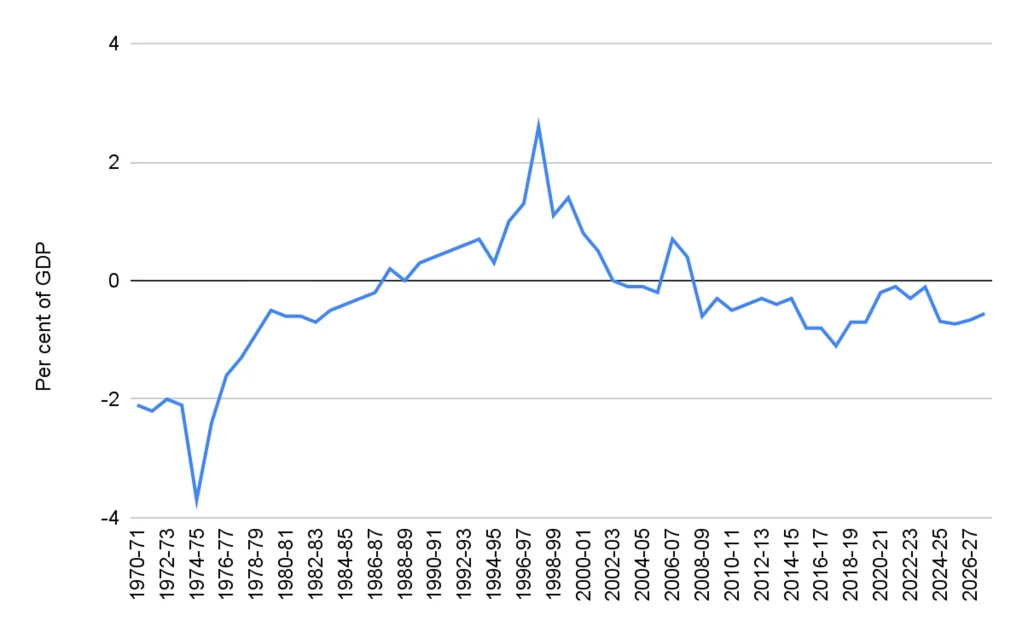

For the federal government, net investments in financial assets for policy purposes have been consistently negative since 2008-09, averaging around -½ % of GDP (Figure 5). For comparative purposes, note that total federal payments have averaged around 25.7% of GDP since 2008-09.

Figure 5. Australian government general government sector net cash flows from investments in financial assets for policy purposes

Source: Australian Government Final Budget Outcome 2022-23, Table B.2., pp. 98-99.

In contrast to the streak of negative flows since the late 2000s, in the 1990s and mid-2000s, net cash flows from investments in financial assets for policy purposes were positive. This was mainly due to privatisations of government-owned businesses such as the Commonwealth Bank, Qantas, and Telstra. The significant negative cash flows in the 1970s are related to federal financing for Post Office capital expenditures, the purchase of planes by state-owned airlines, and the wool reserve price scheme.[11] These years should be regarded as exceptional cases rather than comparison points to argue that current negative cash flows are insignificant.

What have state governments been doing?

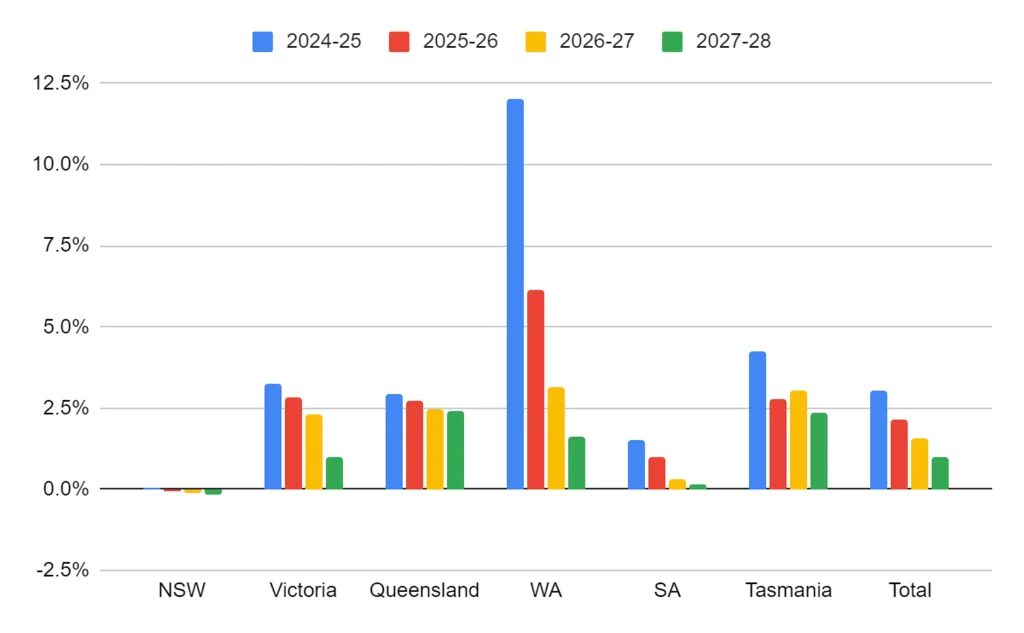

State governments also engage in substantial off-budget activities, although not on the same scale as the federal government in the figures reported in budget papers (Table 2).[12] Over the next four years, Western Australia, Queensland and Victoria will each undertake $10-11 billion of off-budget spending. Over 2024-25 to 2027-28, projected total state off-budget spending of nearly $34 billion is around one-half the size of federal off-budget spending of $77 billion. Collectively, off-budget spending by the federal and state/territory governments will amount to over $110 billion over these four years, or $27-28 billion annually on average. That is around 1% of Australia’s $2.7 trillion GDP.[13]

Table 2. State government investments in financial assets for policy purposes, net cash flows, $ million

| 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | Total | |

| NSW | -26 | 101 | 134 | 209 | 418 |

| Vic | -3552 | -3104 | -2525 | -1126 | -10307 |

| Qld | -2,984 | -2,765 | -2,532 | -2,486 | -10,767 |

| WA | -5,870 | -2,901 | -1,510 | -784 | -11,065 |

| SA | -473 | -320 | -107 | -50 | -950 |

| Tas | -450 | -288 | -313 | -235 | -1,286 |

| Total | -13,355 | -9,277 | -6,853 | -4,472 | -33,957 |

Source: State government budget papers.

Relative to the size of its total on-budget spending, Tasmania also stands out as having notable off-budget spending (Figure 6). But in recent years, WA has had the most substantial off-budget spending. The elevated values in 2025-26 and 2026-27 appear related to a reprofiling of infrastructure spending over the years, with saved proceeds invested to be spent later, as well as equity injections for government-owned enterprises such as Pilbara Ports Corporation and the Water Corporation for the $2.4 billion Alkimos desalination plant.[14] Tasmania’s off-budget spending is likely related to investments in GOCs to cover major purchases such as TT Line’s new ferries.

Figure 6. Net cash flows in financial assets for policy purposes relative to on-budget spending

Source: State budget papers.

Note: On-budget spending is defined as cash flows regarding outlays for transactions plus net cash flows in the acquisition of non-financial assets.

Assessment of off-budget activities

Using off-budget or extra-budget funds while serving the government’s policy agenda is not without risks. It can potentially erode transparency and accountability and threaten the government’s balance sheet. Furthermore, to the extent investments are underperforming, they can add to the debt burden and require higher taxes for debt service in the future, all else equal. This paper deals with these three critical issues of transparency and accountability, balance sheet risk, and underlying economic consequences in the following subsections.

Transparency and accountability

Through off-budget entities, governments can gain some distance and political cover regarding activities for which they should be accountable. Problems include the potential for commercial-in-confidence claims to limit information disclosure and an increase in the complexity of tracking the government’s financial exposure. There are multiple examples of off-budget entities reducing transparency and accountability.

For example, the 2018 Senate Economics References Committee inquiry into NAIF found inadequate transparency and recommended improvements to its disclosure practices.[15] Furthermore, the NAIF was criticised by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) in 2019. The ANAO found “While NAIF has established appropriate governance and policy frameworks, decision support processes were not sufficiently transparent or evidenced to demonstrate projects have been treated in a consistent manner.”[16] The NAIF, however, disagreed with the ANAO’s finding regarding transparency.[17] The current federal government is undertaking a review of NAIF, and it is likely stakeholders will raise concerns over NAIF transparency as an important issue.

The NBN has also received significant criticism. Tooran Alizadeh, now Associate Professor in Urbanism and Infrastructure at the University of Sydney, observed in 2017, “Ongoing secrecy around the NBN, a project that’s likely to cost more than A$50 billion, makes it impossible for the public in most cases to know when and what quality service they will receive.”[18] Furthermore, there is evidence that the rollout of the NBN was affected by political considerations, which, as a PNFC, it should be immune to — except to the extent that governments set community service obligations for equity reasons.

Currently, there is a lack of clarity around off-budget spending, and one recommendation of this paper is for governments to improve their reporting on off-budget spending. The Productivity Commission observed that federal investment vehicles differed in their reporting on the extent of concessional finance, with CEFC and Housing Australia disclosing concessional finance in their annual reports while others, such as Export Finance Australia, do not.[19]

Balance sheet risks

Because of the budget treatment, off-budget activities can reduce the government’s net financial worth, even though the fiscal balance may not reflect the loss.[20] Revaluations can be especially significant. By their nature, being directed at some specific policy objective and not done for commercial reasons, these activities can involve significant risks of underperforming loans or other investments, leading to write-offs of certain debts as bad debts and write-downs of the asset value of the government’s investment.

The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) has highlighted the significant impact on the federal government’s net financial worth of the HELP program, an impact that is not fully apparent in the budget reporting. It notes:

“In 2018–19, around $7.1 billion in new HELP loans were issued, and $1.2 billion of these were not expected to be repaid.24 This revaluation component of the cost to the Commonwealth Government of the loans for that year was therefore expected to be around $1.2 billion…While the $1.2 billion of loans not expected to be repaid is incorporated into the fair value estimate of the HELP loan portfolio that is included in the budget documents’ forecast balance sheet (for instance, in net financial worth), it is aggregated with other expected revaluations and is not readily identifiable as a cost of HELP.”[21]

The government’s investments or loans for policy purposes, in particular, carry the risk of not being commercially viable. The government may accumulate significant debt to finance off-budget uses, and there is a potential for future write-offs. The increasing use of off-budget funds, therefore, calls for rigorous monitoring to protect the interests of taxpayers.

A significant concern is the proliferation of off-budget financing agencies for policy purposes, which add risk to government balances and can represent a poor return on investments backed by taxpayers. For several years after the debacle of failed state banks in Victoria (due to its investment banking arm, Tricontinental) and South Australia in the early 1990s, governments were wary of getting involved in banking activities. The failure of the state banks substantially worsened the financial positions of Victoria and South Australia and prompted significant budget repair measures and privatisation of assets. However, since the 2008 financial crisis, governments have had a renewed interest in using off-budget financial entities for policy purposes.

The federal government at least is required to declare risks to its balance sheet due to the 1998 Charter of Budget Honesty. It does this in the Statement of Risks in Budget Paper, in which it notes various contingent liabilities — i.e. liabilities that would exist if certain events were to occur. For example, in the 2024-25 Budget, it acknowledged the fiscal risk associated with Snowy Hydro, although it does not quantify the possible size of the fiscal risk that could come from project cost overruns or delays.[22] State governments also declare various contingent liabilities in compliance with accounting standards.

Underlying economic consequences

Given these off-budget activities ultimately result in higher debt and net interest payments, owing to write-offs (e.g. HECS-HELP bad debts) and low returns on investments, they imply higher taxation than otherwise in the future, all else being equal. Taxation brings with it efficiency losses. For instance, recent estimates of the marginal excess burden of taxation for income tax and the GST are 34 cents and 24 cents for every dollar raised, respectively.[23]

In a paper presented at a 1981 OECD meeting of senior budget officials and republished in 2007 by the OECD because the problem remained, Professor Allen Schick identified: “Off-budget expenditures weaken budget control.”[24] Hence, this has led to an expanding public sector.

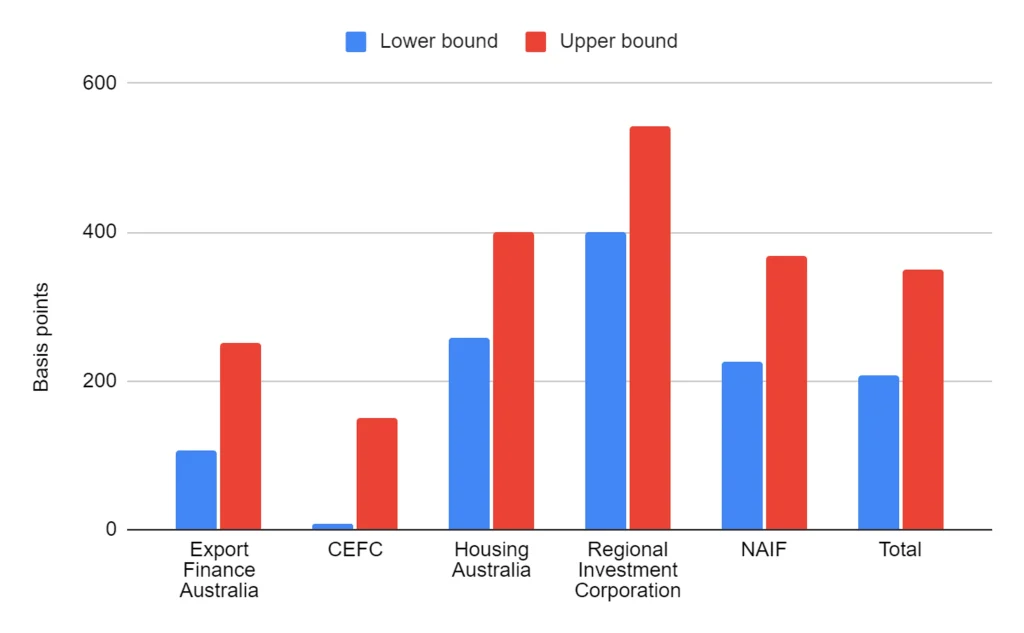

Several off-budget entities are effectively engaging in industry policy, with the risk of diverting economic resources away from more efficient uses, leading to lower productivity and living standards for Australians. Evidence supports this proposition. The poor return for taxpayers is illustrated by the Productivity Commission’s analysis of the investment performance of federal off-budget entities (Figure 7). Across all the investment vehicles, the federal government is sacrificing at least 2 percentage points and up to nearly 4 percentage points through offering concessional finance via these entities rather than lending at market rates and terms. In dollar terms, this corresponded to a loss of $211-356 million.[25]

Figure 7. Underperformance of Commonwealth investment vehicles, basis points, 2022-23

Source: Productivity Commission (2024, Table 1.5, p. 23).

One reason to expect lower returns through investments made by off-budget entities is that investments are often politically motivated rather than commercially motivated. Investments via the CEFC or in Snowy Hydro may be motivated by the net-zero agenda rather than commercial realities. Recent federal investment in Snowy Hydro, for Snowy 2.0, has been embarrassing. The project is well behind schedule and has experienced huge cost blowouts (from an initial $2 billion to $12 billion), partly due to unexpected hard rock. Indeed, a tunnel boring machine was temporarily stuck in a tunnel in 2023.[26]

Another example of a government investment yielding a poor return is the NBN, which was not supported by a credible cost-benefit analysis (CBA) or business case. This is especially concerning, given the project was initially costed at $43 billion, and its cost has blown out to at least $57 billion and will end up at nearly $70 billion.[27] An independent evaluation by economists Henry Ergas and Alex Robson concluded that the project failed a CBA.[28] Politics figured mainly in the commissioning of this project. Prime Minister Kevin Rudd saw it as an “historic act of nation building.”[29]

It would be wrong to assume that all off-budget spending is bad, as some may serve a legitimate purpose. For example, income-contingent loans for higher education (i.e. HECS-HELP loans) may be justified by the fact students cannot use their human capital (i.e. future earnings potential) as collateral for student loans.[30]

That said, the rationale for off-budget activities is, in many cases, deficient. For many activities, there is no apparent market failure. This is particularly the case for the financing entities. There is no lack of financing for sound projects. Indeed, regarding one prominent example, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) found the WestConnex toll road tunnel project in Sydney could have been entirely privately financed and did not need the $2 billion concessional loan it received from the federal government.[31]

In a 2017 pre-budget submission, Infrastructure Partnerships Australia CEO Brendan Lyon observed: “Commonwealth Government funding support is needed for infrastructure — Commonwealth financing is not.”[32] That is, where there is a legitimate public purpose behind supporting infrastructure, it should be supported via grant funding from the budget rather than surreptitiously through concessional finance from an off-budget entity.

The IMF has raised concerns about Australia’s proliferation of off-budget entities in current macroeconomic conditions with inflationary pressures. In its 2022 Article IV report for Australia, the IMF noted:

“Implementation of below-the-line activity through newly created investment vehicles (National Reconstruction Fund, Rewiring the Nation, and Housing Australia Future Fund) should be phased appropriately, and, more broadly, a proliferation of such vehicles should be avoided.”[33]

The IMF has historically been critical of such Extra-Budgetary Funds (EBFs), based on transparency grounds and macroeconomic management.[34] This is because EBF activity can add to the fiscal stimulus from the budget in a way the government or public may be unaware of, contributing to inflationary pressures.

In summary, outside of a few cases where they may address legitimate market failures (e.g. income-contingent loans for higher education), off-budget activity is very likely to have adverse economic consequences, including:

- Lower productivity and living standards if economic resources are diverted to less efficient activities;

- An additional productivity and living standards reduction resulting from the efficient cost of taxation needed to make up for losses on off-budget activities; and

- Adverse macroeconomic impacts where extra-budget activity means the government’s fiscal stance is inappropriate given economic conditions.

Finally, off-budget activities may have equity impacts that are considered undesirable by many Australians. The federal government’s announced write-off of HELP debt, contingent on remaining in government following the next election, is arguably dubious from an equity perspective as graduates earn higher incomes on average than non-graduates. Furthermore, they are more likely to come from higher socio-economic backgrounds than non-graduates.[35]

Conclusions

Much of the off-budget spending we have seen in recent years is concerning. Unfortunately, these off-budget activities started proliferating after the 2008 financial crisis. We should expect more of them in the future as they offer a way for politicians to appear to be responding to society’s challenges while minimising the direct budget impact — even though they bring significant risks onto the balance sheet. They can come at a high opportunity cost through underperforming investments.

Taxpayers suffer through underperforming investments of taxpayer funds. It is bad for accountability and transparency and makes the RBA’s monetary policy task of controlling inflation more difficult. Furthermore, it adds risks to the government balance sheet; particularly the risk of bad debts from uncommercial investments or lending. There is also the risk that governments could strike poor deals with private sector consortia in PPPs. None of this is to say there may not be legitimate off-budget transactions, but instead, off-budget spending is being undertaken much more than is justified.

Sunlight is the best disinfectant, and much greater disclosure on the nature, opportunity costs, and risks of off-budget activities is needed across Australian governments. Specific recommendations include:

- Quantification of the fiscal risks associated with off-budget activities to be attempted and included in budget papers (e.g. in the federal government’s Statement of Risks), so that governments and taxpayers are not surprised by significant financial impacts if risks crystalise in the future;

- An itemisation of the components of revaluations affecting the general government sector in budget papers;

- The identification of the public debt interest cost of budget measures in budget measure descriptions;

- Further analysis by the PBO and Treasury of the implications of off-budget activities for public finances — e.g. simulations of the trajectories of gross and net debt under different scenarios; and

- Developing a consistent standard for the reporting of concessional finance across government-owned entities.[36]

Greater transparency around off-budget activities is essential for an informed public discussion of the benefits and costs of such activities and can help prevent the excessive growth in the scope and scale of government that is leading to escalating public debts across Australia.

References

Alizadeh, Tooran (2017) “The NBN: how a national infrastructure dream fell short”, The Conversation, Published: June 5, 2017, https://theconversation.com/the-nbn-how-a-national-infrastructure-dream-fell-short-77780, accessed on 13 November 2024.

Allen, Richard and Dimitar Redev (2006) “Managing and Controlling Extrabudgetary Funds”, IMF Working Paper, WP/06/286.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2015) Australian System of Government Finance Statistics: Concepts, Sources and Methods, Part C – The classification of sources and uses of cash, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/detailed-methodology-information/concepts-sources-methods/australian-system-government-finance-statistics-concepts-sources-and-methods/2015/12-statement-sources-and-uses-cash/part-c-classification-sources-and-uses-cash, accessed on 14 October 2024.

Australian National Audit Office (2017) The Approval and Administration of Commonwealth Funding for the WestConnex Project: Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development Infrastructure Australia.

Australian National Audit Office (2019) Governance and Integrity of the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility, Auditor-General Report No.33 2018–19.

Becker, Joshua and Floss Adams (2024) “Snowy Hydro boss doubles down on project timeline despite slow progress and budget blow-out”, ABC News, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-05-09/snowy-hydro-project-timeline-on-track-snowy-2-boss-florence/103820240, accessed on 18 October 24.

Carling, Robert (2024) Government Spending and Inflation, Centre for Independent Studies, Policy Paper 58.

Chapman, Bruce (2005) “Income Contingent Loans for Higher Education: International Reform”, Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper no. 491.

Ergas, Henry and Alex Robson (2009) “The Social Losses from Inefficient Infrastructure Projects: Recent Australian Experience”, Productivity Commission Round Table

Gregory, Mark (2024) “What’s next for the National Broadband Network? Labor and the Coalition’s plans compared”, The Conversation, Published: April 11, 2022, https://theconversation.com/whats-next-for-the-national-broadband-network-labor-and-the-coalitions-plans-compared-180571, accessed on 14 November 2024.

The Hon Anthony Albanese MP, Prime Minister, The Hon Jason Clare MP, Minister for Education, The Hon Amanda Rishworth MP, Minister for Social Services, The Hon Andrew Giles MP, Minister for Skills and Training (2024), “Albanese Labor Government to cut a further 20 per cent off all student loans debt”, Joint Media Release, 3 November 2024, https://ministers.education.gov.au/anthony-albanese/albanese-labor-government-cut-further-20-cent-all-student-loans-debt, accessed on 14 November 2024.

International Monetary Fund (2023) Australia: 2022 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; and Staff Report, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2023/01/26/Australia-2022-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-and-Staff-Report-528629, accessed on 14 October 2024.

Lyon, Brendan (2017) Infrastructure Partnerships Australia Pre-Budget Submission on the Proposed Establishment of an ‘Infrastructure Financing Unit’ (IFU).

Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (2019) Summary of NAIF response – ANAO: Governance and Integrity of the NAIF, https://www.naif.gov.au/media/5y4n0lvi/summary-of-naif-response-letterhead.pdf, accessed on 13 November 2024.

OECD (1976) OECD Economic Surveys: Australia.

Parliamentary Budget Office (2020) Alternative Financing of Government Policies: Understanding the fiscal costs and risks of loans, equity injections and guarantees, Report No. 01/2020.

Productivity Commission (2023) Trade and Assistance Review 2021-22.

Productivity Commission (2024) Trade and Assistance Review 2022-23.

Rudd, Kevin (2009) “Realising our broadband future”, speech to University of New South Wales, Sydney, 10 December 2009, https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-16970, accessed on 18 October 2024.

Schick, Allen (2007) “Off-Budget Expenditure: An Economic and Political Framework”, OECD Journal on Budgeting, vol. 7, no. 3.

Senate Economics Reference Committee (2018) Governance and operation of the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (NAIF).

Tomaszewski, Wojtek, Ning Xiang and Matthias Kubler (2024) “Socio-economic status, school performance, and university participation: evidence from linked administrative and survey data from Australia”, Higher Education, published online 4 June 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01245-7, accessed on 13 November 2024.

Tran, Chung and Wende, Sebastian (2017) “On the Marginal Excess Burden of Taxation in an Overlapping Generations Model”, ANU Working Papers in Economics and Econometrics, no. 652.

Tunny, Gene (2018) Beautiful One Day, Broke the Next: Queensland’s Public Finances since Sir Joh and Sir Leo, Connor Court, Brisbane.

Verrender, Ian (2020) “NBN missed almost every mark, but there is a chance for the Government to avoid total failure”, ABC News, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-08-17/nbn-failure-infrastructure-project-government-should-cop-loss/12563994, accessed on 14 October 2024.

Endnotes

[1] Schick (2007, p. 4).

[2] Australian Government Budget Paper no. 1, p. 351.

[3] Productivity Commission (2024, p. 20).

[4] The Hon Anthony Albanese MP, Prime Minister et al. (2024).

[5] Carling (2024).

[6] The Commonwealth’s UCB is closest to the state’s fiscal balances, although the UCB is on a cash basis rather than an accrual accounting basis.

[7] See Australian Government Budget Paper no. 1, p. 401, regarding their status as “specialist investment vehicles inside the GGS”.

[8] Verrender (2020).

[9] Tunny (2018, pp. 195-196).

[10] See https://www.nrf.gov.au/ and https://naif.gov.au/.

[11] See for example OECD (1976, p. 30) and Parliament of Australia Hansard, 17 September 1974, p. 1282.

[12] That said, the comparison is imperfect because the Commonwealth figures include some lending from the general government sector to PNFCs, because the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM) is considered part of the general government sector. However, at the state level, state treasury corporations are classified as public financial corporations and PNFCs borrow from the treasury corporations, meaning loans from the general government to PNFCs are not a significant part of net cash flows in financial assets for policy purposes.

[13] One trillion is one thousand billion (or one million million).

[14] See WA Government Mid-Year Financial Projections Statement 2023-24, pp. 20-24.

[15] Senate Economics Reference Committee (2018, pp. 29-30).

[16] ANAO (2019, p. 8).

[17] NAIF (2019).

[18] Alizadeh (2017).

[19] Productivity Commission (2023, p. 33).

[20] Parliamentary Budget Office (2020, p. 15).

[21] Ibid.

[22] Australian Government 2024-25 Budget Paper no. 1, p. 292.

[23] Tran and Wende (2017, p. 1).

[24] Schick (2007, p. 28).

[25] Productivity Commission (2024, p. 23).

[26] Becker and Adams (2024).

[27] Gregory (2022).

[28] Ergas and Robson (2009).

[29] Rudd (2009).

[30] Chapman (2005, p. iv).

[31] ANAO (2017, p. 38).

[32] Lyon (2017, p. 10).

[33] IMF (2023, p. 11).

[34] Allen and Radev (2006, p. 16).

[35] Tomaszewski, Xiang and Kubler (2024).

[36] Recommendations 2 and 3 were inspired by PBO (2020).