Published in Get Britain Building by the Fabian Society

The housing policy debate in Australia has focussed on land use regulations (often referred to as zoning or planning restrictions). In this contribution I discuss estimates of their effect, then the policy debate and how it differs from other countries. I then summarise recent policy initiatives and difficulties.

Estimates

Planning restrictions are a major reason why housing in Australia is so expensive. For example, they are estimated to raise the price of the average apartment in Sydney by 37%. Table 1 shows some other estimates. This uses the most popular approach, the difference between sale prices and the marginal cost of supply, which Glaeser and Gyourko call the “zoning tax”. These estimates essentially represent the value of permission to build, which the zoning system keeps scarce and hence expensive.

Table 1: The Contribution of Planning Restrictions to Property Prices

| Detached Houses, 2016 | Apartments, 2022 | |||||

| $AUD * | % of price | $AUD * | % of price | |||

| Sydney | $489,000 | 42% | $357,000 | 37% | ||

| Melbourne | $324,000 | 41% | $128,000 | 19% | ||

| Brisbane | $159,000 | 29% | $17,000 | 3% | ||

| Perth | $206,000 | 35% | ||||

| Source: | Kendall and Tulip | NSW Productivity Commission | ||||

* AU$1 = US$0.67 or £0.52

The estimates strike many observers as surprisingly high. However, they are in line with other information, including the increase in land value that accompanies upzoning (Kendall and Tulip, Appendix A; Millar, Vedelago and Schneiders). They are also in line with the market value of land, which increases with the number of apartments allowed to be built on it (Knight Frank p3). The estimates are qualitatively similar to those found in expensive cities in the United States (Gyourko and Krimmel), Canada (von Bergmann and Lauster; CMHC), New Zealand (Lees), and elsewhere. And they are supported by an enormous quantity of other research (Been, Ellen, and O’Regan; Schleicher; Barr; Gleeson; Hoskins) which finds large effects of zoning restrictions using a wide variety of approaches and data.

The policy debate

These research results have been emphasised in public discussion and government reports. This includes the Commonwealth Productivity Commission, the NSW Productivity Commission (2021, 2023, 2024), the Parliamentary (Falinski) Inquiry into Housing Affordability and the 2024 Commonwealth Budget Papers (Budget Paper 1, Statement 4).

A few vocal planning academics dissent from the research consensus (Phibbs and Gurran; Pawson et al). I have argued that their objections are simple misunderstandings (Tulip, 2021). For example, they attribute high prices to strong demand rather than unresponsive supply, not recognising that these factors interact; the explanations are not alternatives. The market failure is that supply does not respond to the increased demand. When challenged, the “supply deniers” have not defended their position.

Of more importance, the wider public is not convinced by the research. The Susan McKinnon Foundation (p133) asked 3000 Australians “In your opinion, what impact will building more homes in your city/suburb/neighbourhood have on housing prices?” Only 27% of respondents agreed with the economic research that it would reduce prices. A third replied it would actually increase prices with the remainder being neutral or not responding. These responses are similar to those reported in US opinion polls (Nall, Elmendorf and Oklobdzija).

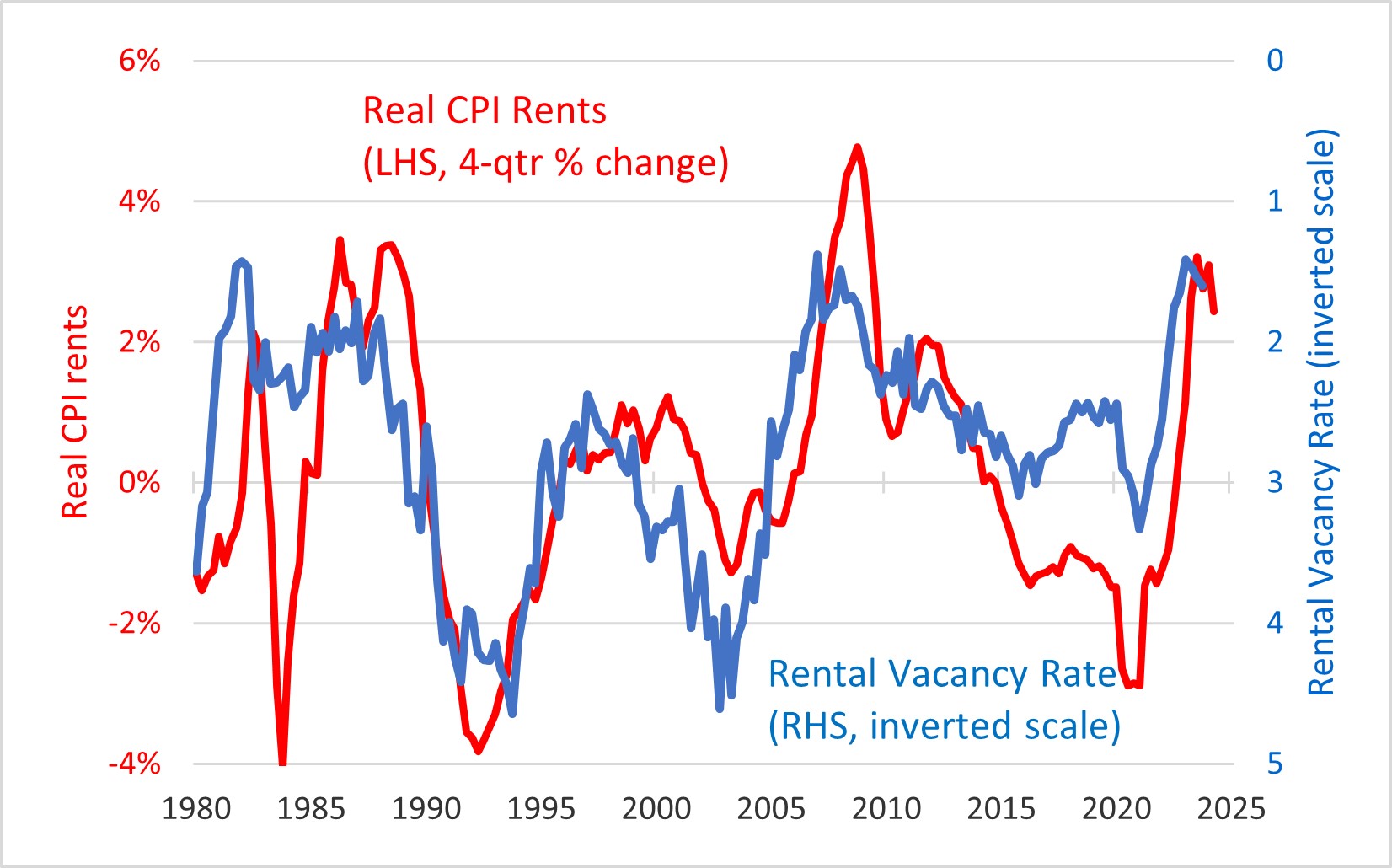

The public responses are difficult to understand given the very clear effect of supply and demand on the cost of housing. For example, as Chart 1 shows, the rental vacancy rate (properties advertised as available for rent divided by the stock of rental housing) drives changes in real rents. As of mid-2024 , rents are rising quickly and this seems clearly attributable to the tightness of the housing market.

Chart 1: Vacancy Rate and Change in Real CPI Rents; Australia

Source: Saunders and Tulip, updated.

Note that the same close relationship is evident in Canada and the United States

That the public does not see increased supply as the remedy is a puzzle and a major obstacle to better policy. There are many suggested explanations; one being that the public has difficulty with economists’ assumption that “other things are equal” (specifically, demand).

Political rhetoric has swung dramatically in the past few years. There is now a bipartisan consensus that housing affordability is one of the country’s very top social problems and that the solution is “supply, supply, supply” to quote the then Federal Minister for Housing, Julie Collins. Politicians from both major parties, including the NSW premier and the Queensland housing Minister, self-identify as “YIMBYs”. Leading newspapers, including the Australian Financial Review, the Sydney Morning Herald and the Age have editorialised in favour of allowing much more density.

Recent policy initiatives

In August 2023 the Prime Minister and state Premiers agreed on a national target of 1.2 million new homes over 5 years, emphasising the need for looser planning. The Federal government is providing up to $4.5 billion to assist and encourage States to meet their share of the target.

This target is ambitious if not unrealistic. It is close to recent cyclical peaks, suggesting it is within reach. However, it represents a large increase in construction, which will be difficult to achieve given subdued demand and widespread reports of labour shortages.

The announced targets fall well short of what is needed to solve the housing crisis. An increase in the dwelling stock of about 10 to 15 per cent, in addition to what would normally be supplied, might be needed to eliminate the shortage estimates in Table 1, assuming an elasticity of housing demand of about -0.4 (as estimated by Saunders and Tulip and Abelson and Joyeux). In contrast, the national target represents growth in the housing stock of 2.2 per cent a year, which is only slightly more than trend population growth, about 1.5%. Given that the demand for dwellings per capita increases with income, the reduction in the shortage may be small. Nevertheless, it is a start; and it focuses the discussion on the central issues.

Most of the political debate has occurred at a state government level, where responsibility for land use regulation and many other aspects of housing policy lies. The debate is most advanced in New South Wales (NSW), the most populous and expensive state, where the governing Labor Party has announced a series of policies aimed at boosting supply. One of the most controversial has been Transport-Oriented Development, which allows 6-storey apartment buildings within 400m of 37 train stations, on land that is currently zoned for low density. Another has been the announcement of housing targets for local councils, which sum to 377,000 dwellings, NSW’s share of the national target of 1.2 million dwellings noted above.

These and other policies will be implemented by local councils, which directly administer most planning approvals, subject to state government constraints. However, many councils have signalled opposition and it is not clear how they will be made to co-operate. Councils can be replaced with an administrator, and obstructionist councils have successfully been threatened with this in the past. However, discretionary remedies may provoke obstruction so that the central government is blamed for locally unpopular development, while the councillors portray themselves as fighting for their community. Automatic upzoning might lead to a clearer attribution of responsibility. Foreign remedies, including California’s “Builder’s remedy” and England’s “presumption in favour of sustainable development,” have been suggested as alternatives, though their effectiveness is not clear.

Comparisons to other countries

The nature of the housing debate in Australia has similarities and differences compared with other countries. Overwhelmingly, the opposition to increased density is based on fears that it will change “neighbourhood character” — what is often called a conservative or “right-NIMBY” stance. We have “left-NIMBYs” but they lack influence outside a few niches, in particular the Greens Party (which controls the balance of power in some legislatures), the social housing lobby and the planning profession. They do not control local governments as they do in big US and UK cities and hence they are not a major force to contend with. That means that issues like gentrification are much less important. And our debate is less mainstream versus leftist academics and more experts versus the public.

Though “debate” overstates the quality. There is little dialogue between opposing views. Much public discussion (for example, the Greens party’s call for rent controls and higher taxes on landlords) is not supported by the available research.

As in other countries, divisions over housing policy do not align with conventional political groupings. The right is split, with many free marketeers being leading advocates for zoning reform, opposed by conservatives who fear change. The left is also split, with egalitarians who want to transfer income from wealthy landowners to lower income renters being opposed by interventionists who mistrust the market.

Opinion is divided

Opinion polls show the public supports proposals to increase density as an abstract principle. For example, 50% of NSW voters support plans to put medium density around train stations while 31% oppose. However, nearby residents loudly oppose actual proposals. Politicians, especially on local councils, appear to be very sensitive to this opposition. It is not clear how this inconsistency should be resolved. So tensions will remain between central governments wanting housing affordability, and local governments wanting to restrict supply.