Introduction

There is nothing finer in political culture than the idea — the doctrine, the inspiration — that all men and women are equal in their essential human dignity. And following on from that, the idea that within a nation, every citizen is equal before the law and equal before their parliaments and the institutions of the state.

A liberal nation is egalitarian in its institutional outlook, and universal in its civic identity.

So ubiquitous is this idea in the background of our minds, that in some ways we think it self-evident, obvious to everyone. Or, even worse, the idea is so familiar that we forget about it and why it is so special, and sometimes, without quite realising what we are doing, entertain innovations and novel structures that contradict liberalism at its heart, and therefore tend to destroy it.

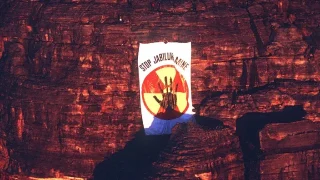

The proposal for a constitutionally guaranteed, elected, policy advisory chamber to be known as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to Parliament, is a direct repudiation of the central tenet of political liberalism. Further, it gives life to the pernicious idea that universal suffrage, the rule of law and representative, democratic institutions are somehow inherently deficient when dealing with all the variety of human racial, cultural and ethnic diversity. This is a dagger at the heart of liberal democracy for if democratic institutions are insufficient for one minority, they might be insufficient for any minority, or indeed even for the majority. The whole project of the Voice represents one part of a tragic wrong turn in Australian politics towards the sterile, chaotic entropy of identity politics.

These are controversial conclusions. And I reach them reluctantly. But they are inescapable. Truth, in the old definition, is conformity of the mind to reality. There is simply no other way of viewing the reality of what the Voice involves. I’ve certainly been attacked, vigorously, sometimes unreasonably, for arguing these conclusions. But the facts are the facts. Truth is truth.

‘Race-blindness’ is part of liberalism

A race-based electoral body in the Constitution contradicts the essential race blindness which our institutions should have, which is an ineradicable element of liberalism.

Among commentators, these conclusions are unpopular. It’s almost an offence against polite society to raise such ideas. But this is a profoundly important step Australia is considering. It would change the basis of citizenship and therefore change the nature of citizenship. For if citizenship assumes different categories, if there are different grades of citizen, if people can be different types of citizen because of their racial background, then the nature of citizenship is no longer universal. That means citizenship has not changed just for Aboriginal Australians who can vote for the Voice. Citizenship is then changed for everyone. And changed for the worse, because it’s no longer a universal quality that we share.

Because these issues are so important, and because these opinions are so controversial, it’s worth trying to think them through, from first principles, at a little length. And although first principles are at stake everyone brings their personal experience to the issue, including me. Your personal experience, whatever it is, doesn’t justify extolling a bad principle, but it can explain how you journey to a good principle.

Regarding the Voice as a mistake does not suggest any hostility to Aboriginal Australians. In my case, it is partly out of love of Aboriginal Australians that I am so grieved by this proposal. Aboriginal Australians were dispossessed and frequently persecuted in Australia. Partly as a result of that history, many Aborigines continue to suffer disadvantage today. Like most Australians, I honour Aboriginal culture and benefit from Aboriginal wisdom.

My first Aboriginal friend came into my life when I was nine, at St Thomas’ Superior School for Girls (we boys were a kind of afterthought at St Thomas, and we didn’t stay till the top grades, but were exiled to the Christian Brothers in Year Five) in the inner western Sydney suburb of Lewisham. Some time in Grade Four, a new boy, Raphael, an Aborigine, joined our class and sat next to me. He came from Temora way.

Like me, he was good at reading, but unlike me, he was really sharp at ball sports. Even then, I was shaped like a potato and had the natural coordination of a blancmange. Being Raphael’s friend entailed some reflected sports glory for me. In any event, we told each other about our lives, as kids do. We sat together in class and played together in the playground and hung around a bit after school, in those innocent times when nine year olds could safely come home a bit late. We were friends.

Catholics and some other Christians have a sacrament called Confirmation — like a Jewish bar mitzvah but not as much fun — in which we get to take a saint’s name as an extra name. I found that Raphael’s name was that of an Archangel and so I chose that for my Confirmation name.

I had religious motivations for this, for I have always been a fan of angels, but I also had a more earthly motivation. Raphael was my best friend at a time in life when best friends are important. Taking his name as my name, I thought, would bind us together. He left our school after a few months. We tried to stay in touch, but this is not so easy for nine year-olds. He had encouraged me to write to his sister in Temora, who was proud of her little brother in Sydney. But her letters to me were quickly lost and I have no idea how Raphael’s life went after he left our school. Still, to some extent my plan worked, we did stay connected. For I can never think of my Confirmation name without thinking of my friend.

We were innocent of racial politics as kids. But even then, in the mid-1960s, my school class was ethnically and racially diverse, with the first Asians supplementing the many Mediterraneans — Italians, Greeks, Lebanese — and East Europeans I grew up with. So there were Ngans and Rodriguezes and Saads and Scarfones as well as the regular Irish Catholic names, the Walshes and Kennedys and Kellys.

My father was intensely proud of his Irish heritage, and deeply involved with it. As a kid, my mind was filled with Irish legends. We were happy that John F Kennedy was president for a while. My father explained that the racist Ku Klux Klan in the United States hated blacks and Jews and Catholics. That’s just the way I wanted it. I wanted to stand with the blacks and the Jews. I was proud the Klan hated us too.

So I grew up with a pro-aboriginal bias and have benefited from modest Aboriginal friendships over the years. I carried that bias into professional journalism, which I entered nearly 45 years ago. I still have that bias today and it gives me no psychic joy at all to be at odds with a good portion of Aboriginal leadership in this country.

But a slice of Aboriginal leadership has made a terrible mistake in travelling down the dry gulch of identity politics. I don’t say this as someone who wants to privilege any particular Anglo, or even Irish, identity of my own. My wife is of non-Caucasian background, so are my sons and grandchildren, my extended family is overwhelmingly non-Caucasian. I have by choice spent, cumulatively, years of my working life in Southeast Asia. And yet I’ve been accused of racism for opposing the Voice. That doesn’t matter as far as I’m concerned. I am not remotely persecuted or looking for sympathy. But it says something about the desperate, almost panic-stricken illiberalism with which this initiative is being pursued.

Humanity is distinctive and universal

Liberalism is not a rejection of change. Liberalism is a positive and magnificent vision. The debate about the Voice should force us to reconsider and reaffirm the basic idea of liberalism. That basic idea centres on a distinct conception of the human condition. Perhaps the defining programmatic effort of liberalism over the past couple of centuries has been to remove race and gender altogether from civic status, from civic rights and obligations.

But even this is too negative a way to express the core idea of liberalism. This idea has twin components — that humanity is utterly distinctive, and utterly universal. These ideas require a little elucidation. They are by no means self-evident in all cultures and all settings. Even in cultures which honour them in name, such as ours, they are frequently dishonoured in practice.

What does it mean, that human nature is both distinctive and universal? The distinctiveness of human nature is an assertion that there is nothing above the human being and nothing else in nature the same as a human being. After all, if humanity is not utterly distinctive, then there is no ultimate claim for universal human rights. Humanity is then just another chancy outcrop of the biosphere.

The challenge to the distinctiveness of human nature, and the moral consequence of that distinctiveness, comes from many quarters today. Some time ago I appeared on an ABC Q and A program with the atheist philosopher, Peter Singer. He is a good contributor to public life and a very useful philosopher because he thinks ideas through to their logical conclusions.

On that program I had occasion to put to Singer arguments he developed in Rethinking Life and Death, and in Animal Liberation, that severely handicapped babies should be left to die if their parents don’t want to care for them, that severely handicapped people have less utility than a sentient mammal, a cat or a dog.

At one point in our dialogue he said to me words to the effect of: “But Greg, do you really think they should be kept alive just because they are members of our species?”

Yes, that’s exactly what I think, just because they are human beings. The utility of a cat or dog cannot be compared to that of a human being. That’s because of the irreducible distinctiveness of human nature. The distinctiveness of the human condition flows directly into its universality. A person is a person whether they are in New York or New Delhi, Paris or Papua New Guinea, whether they are a school teacher in Kyiv, a nurse in Buenos Aires or a Rohingya in Myanmar. Each human being is a human being, with ineradicable human dignity and human rights. And indeed at some point, whenever we penetrate another culture, we find primarily not strangeness, but abiding familiarity.

No nation offers its citizenship to the whole world, or at least not automatically. But within each nation with any trace of liberalism in its cultural DNA, the arc towards that universalism, which recognises the distinctiveness and universality of the human condition, bends towards a universal citizenship within the nation’s borders. By this I mean that as far as the state has an official civic view of each person, each person enjoys the same rights and suffers the same obligations.

That doesn’t mean that people are all the same, or even mostly the same, or even should be the same, or have the same culture. In a free society like Australia, culture is substantially a matter of choice.

Evolution of the liberal conception of ‘human being’

These ideas of human distinctiveness, and universal humanity, took a long time to develop in the West. The best treatment of this evolution of the liberal conception of the human being is offered by the Oxford scholar Larry Siedentop in his magisterial Inventing the Individual, the Origins of Western Liberalism.

Sidentop argues the striking case that most of the things we like about liberalism had been thought through by the late Middle Ages. But his larger thesis is that liberalism derives from the working through of the Jewish and Christian traditions. Not the repudiation of these traditions but the working through of these traditions.

The first great universalist statement of human rights in the ancient world comes in what Christians call the Old Testament and Jewish communities revere as the Hebrew Scriptures. In the Book of Genesis, God creates humanity in his own image, in the image of God. That was not remotely the common view of humanity in the ancient world. The ancient world was full of hierarchies it regarded as essential, often enough based on race, and always including considerations of gender and property. The Christian repudiation of existential or innate hierarchy became ever more explicit. Siedentop argues that St Paul turned the ancient world upside down, especially with his cri de coeur of universalism: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male and female, but you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

The oneness of humanity, which is the essence of liberalism, can never regard race as determinative.

Siedentop argues that the very idea of the individual having a separate immortal relationship with the all-powerful God of monotheism, rather than having such a relationship mediated through family or clan or tribe, and indeed being seen essentially as a member of such a group, was also a revolution for the consciousness of the ancient world.

This intrinsic human individualism, which certainly does not mitigate against social solidarity, is an intensely radical proposition and it races through history in remarkable ways. St Benedict in the 6th century set up what became the immensely influential tradition of Western monasticism, but he also contributed to universalism and egalitarianism. The Rule of St Benedict, which is still in print today, 1400 years after it was written, became the model for most subsequent Christian monasticism. Here’s where liberalism was revealed in the unlikely setting of the monastery. The monasteries were the first self-governing, democratic institutions. The monks elected their own abbots. Plenty of former noblemen and plenty of former slaves became monks. Yet all wore exactly the same clothes, the monks’ habits, and lived in close and cooperative proximity.

Plenty of Christians did bad things over 2000 years but the impulse towards a universal view of human nature, and the consequent view of universal human rights, was overwhelmingly Christian. Plenty of Christians, to their shame, owned slaves or supported slavery. But there was also always strong Christian opposition to slavery. The campaign to abolish slavery, both William Wilberforce in Britain and the abolitionists in the US, was again overwhelmingly Christian in inspiration.

As I say, these are not self-evident truths across the globe. Vladimir Putin’s preferred ideological guru, Aleksandr Dugin, in his dark and strange writings, argues not only for the mystical connection of the Russian race to all Russian territory, which for him includes Ukraine. But he actually argues that individuals don’t have rights, nations have rights, and by nations he means peoples, racially defined, especially the ethno-construct of Russians. Similar ideas, in less exotic fashion, animate the metaphysics of the Chinese Communist Party, that the Chinese individual should find existential meaning in the service of the Chinese state and the Chinese Communist Party.

One of the most pernicious associations of race with supposed moral attributes, racially inherited “rights” or qualities, so to speak, was the old Christian prejudice of anti-Semitism which held the Jewish race responsible for the death of Christ and therefore all Jews in history bore some blame. This was never Christian doctrine and it is a wretched and terrible notion. Nonetheless, these toxic associations of ethnicity with morality and collective guilt or virtue are hard to eradicate. The Second Vatican Council of the Catholic Church in the 1960s regarded this dreadful inheritance of anti-Semitism, based on the idea that a whole race can carry guilt or virtue, as so obnoxious that it made a severe, authoritative and lengthy statement proclaiming its falseness.

For the truth is that virtue or vice is an individual matter. Though my father be an axe murderer, and both my grandfathers, and all four of my great grandfathers, still I am not an axe murderer. I determine what I am through my own actions. Though my mother be a saint, and both my grandmothers, and all four of my great grandmothers, still I am not a saint. I demonstrate what I am through my own actions.

Preferential treatment cannot compensate historical wrongs

A liberal state should never accept that there is either entitlement or disenfranchisement, virtue or vice, superiority or inferiority, in any racial category. Yet enshrining in the Constitution an elected Aboriginal Voice to Parliament does exactly that. It is wrong in principle.

What about righting the wrongs of history? What about compensation for past injustice? What about setting things to right?

A fundamental tenet of liberalism is that within a liberal society, individuals have rights. You cannot therefore justly, or even meaningfully, remedy an injustice from 250 years ago, especially on the basis of race. You cannot compensate an injustice of 250 years ago by a preferential treatment today. For that to be even possible the individual can have no identity, but, a la Dugin, only the nation, or the racial identity, has a personality. In the United States, there is a movement to pay African Americans compensation for the historic crime of slavery. Slavery was always wrong and it’s right that it is considered a blight and a tragedy and, morally, a crime.

But you cannot compensate someone today for an injustice suffered by one or more of their ancestors hundreds of years ago. The whole idea is absurd. Should low wage factory workers in West Virginia pay higher marginal tax rates in order to pay historic compensation to Oprah Winfrey or Kanye West? Human beings are fallen creatures. The world abounds in the consequences of historic injustice or displacement. You cannot visit the magnificent Blue Mosque in Istanbul without being aware that it was for a thousand years a Christian cathedral. Yet it would be madness destined to result in conflict to try to run a campaign to have its identity changed now.

My ancestors on my father’s side left Ireland in the decades after the Great Famine of the 1840s, caused by the failure of the potato crop. A quarter of Ireland’s population died or emigrated as a result of the famine. The British Government, which ruled Ireland then, was not responsible for the potato blight but it wanted to clear Irish peasants from inefficiently cultivated land. Potato crops failed in several parts of Europe. Only Ireland starved. British relief efforts in the first year of the Famine were not remotely adequate. Ireland was forced to export food to Britain as its people starved. Tim Pat Coogan in The Famine Plot joins other historians in pronouncing this a deliberate act of British policy. He considers it a crime against humanity.

The idea of Britain now trying to pay compensation to the descendants of victims of the Great Famine would be extreme insanity. As my ancestors probably would not have come to Australia if not for the Famine, I am in some ways a beneficiary of this historic crime. When Tony Blair apologised for Britain’s behaviour in the Famine I didn’t see this as at last righting a historic wrong. I just thought it another absurd bit of nonsense. It’s a great trick to get moral or political credit by apologising for someone else’s crimes.

This may all seem a long way from contemporary Australian debates. But the principle is bad wherever you try to apply it. A liberal society cannot go back and re-adjudicate every historical wrong and then find descendants of those wronged and pay them reparations, even constitutional reparations. Logically such reparations would have to be proportionate to the percentage of someone’s ancestry which was in the victimised group.

This is of course entirely grotesque, monstrous. And it has nothing at all to do with the wholly sensible task of searching out important indicators of disadvantage and doing everything you can to remedy the disadvantage. Thus, a liberal society has to do lots of things for specific groups of people. School kids are governed in their schools by laws that apply to school teachers. It’s not necessary either for the kids or the teachers to be formally recognised in the constitution.

There are programs designed to help refugees to settle successfully in Australia. You could just about imagine a year in which all or almost all of our refugees came from one place, one conflict, one culture. But the program that year to help refugees would still not be racially based, even if all or almost all of its beneficiaries were of one race. And you don’t get refugee help if you were born in Australia but your grandparents were refugees 50 years ago.

There are a number of health, education and welfare programs offered specifically to Aboriginal people. I support such programs. Some of the beneficiaries won’t need them. But it is perfectly reasonable for a society to try to help its disadvantaged members and Aborigines still suffer disadvantage in large numbers. So these programs ought not be seen as endless rights accruing to one racial group, still less as historic reparations being paid to one racial group. Rather they are one way to search out quickly large numbers of people who are disadvantaged. The decent, liberal ambition of such programs is to work themselves out of existence as the disadvantage, hopefully, disappears.

A liberal society seeks to do justice to, and offer assistance to, people who are living in the society whatever their background. An Australian citizen who is a Chinese immigrant from Hong Kong, or an Indian immigrant from Kolkata, or a Hmong hill tribesman from Laos who took out Australian citizenship one day ago, as a citizen is just as good as me, and just as good as Aboriginal Australians. The absolute civic equality of citizenship is its essence.

Turnbull’s original argument was convincing

The idea of a constitutionally enshrined Aboriginal Voice to parliament was formally rejected by Prime Ministers Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison, not because they thought such a referendum would not pass, but because they thought the idea was wrong in principle, was a contradiction of basic liberal principles. Malcolm Turnbull has made an agonising decision to change his mind and support the Voice after all, partly because it has such strong support among much Aboriginal leadership.

I respect his decision and admire his goodwill. But I find the arguments that he originally made against the Voice in his memoir, A Bigger Picture, completely convincing. In fact I recommend the pages of his memoir that deal with this matter as a fine, crisp, clear statement of what’s at stake and why the proposal is so bad.

Turnbull wrote that he wasn’t “comfortable with the Constitution establishing a national assembly open only to the members of one race.” He recalled his statement after the cabinet decision: “Our democracy is built on the foundations of all Australian citizens having equal civic rights — all being able to vote for, stand for and serve in either of two chambers in our national parliament… A constitutionally enshrined additional representative assembly for which only Indigenous Australians could vote for or serve in is inconsistent with this fundamental principle.”

A number of courageous Aboriginal leaders defy the zeitgeist to argue just this case. Warren Mundine, who has had a storied career in business, politics and for a time as an adviser on Indigenous issues to a former federal government, in an interview told me he is opposed to the Voice. He said: “I’m a liberal democrat. I love and believe in liberal democracy. The basis of liberal democracy is that everyone is equal before the law. We fought for decades to be treated as equals. Now there is no law that is discriminatory against Aborigines. Some people talk of two sovereignties — how can there be two sovereignties in one country?”

Mundine has also argued that one Aboriginal nation cannot speak for another Aboriginal nation, has no authority to speak for another Aboriginal nation. Therefore in creating within the Constitution a right for an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to parliament, we are recognising a fictional polity in order to create a new focus of artificial division.

Turnbull in his memoir points out that the biggest concentration of Aborigines is found in western Sydney. So how does it make any political, or indeed Constitutional, or practical sense for Australians of Aboriginal background who live in, say, Parramatta or Bankstown, to offer through an elected body some specific advice on policies which are attempting to assist a remote Aboriginal community in Arnhem Land? This is a nonsense, unless of course we’re really trafficking in the sterile symbolism of identity politics. Or worse, making a cynical play for whatever a power activist class can shake out of the system.

Country Liberal Party senator Jacinta Price gave a magnificent maiden speech to the Senate. It’s a kind of Australian Gettysburg Address and I think all Australians could benefit from reading it. She said: “It would be far more dignifying if we were recognised and respected as individuals in our own right who are not identified by our racial heritage but by the content of our character… It’s time to stop feeding into a narrative that promotes racial divide, a narrative that claims to try to stamp out racism but applies racism in doing so and encourages a racist over reaction.”

In a television interview, Price also made the point that having the Voice forever in the Constitution implies that Aborigines will be marginalised forever, for the whole basis of the Voice is that parliamentary democracy doesn’t work for Aboriginal Australians. The Voice, like all identity politics, is at least a partial repudiation of parliamentary democracy, and the alleged institutional racism that colour blind institutions supposedly embody, not to mention their unconscious bias. I don’t mean to imply that Mundine or Price necessarily share all the views in this paper. But their principled rejection of the Voice is one of liberalism, and it puts them offside with the vast government funded industry of Aboriginal organisational politics, puts them offside with most mainstream media and probably tends to put them offside with many corporations. So it’s right to describe their position on the Voice, in which they defend fundamental liberal principles, as courageous.

Constitution clauses in question

There is an argument that the Constitution already has racial clauses so inserting the Voice is not a departure from Australian constitutional practice. In fact there are only two provisions in the Constitution which relate to race. One is Section 51 which gives the Commonwealth the power to make laws about people of any race. This is a benign but certainly clumsy provision. I’d be happy if it wasn’t there, because I don’t think the Constitution should make any mention of race. It would be OK if the Constitution said the Commonwealth could make laws regarding any Australians. The purpose of that section is to allow the Commonwealth to make laws which help Aboriginal communities.

Section 25 of the Constitution prevents states counting people in their census, and therefore for the allocation of seats in parliament, if they have disqualified them from voting by race. The whole idea of disqualifying anyone from voting because of race is obnoxious. The specific constitutional provision is also anachronistic. The Racial Discrimination Act prevents any state from banning any racial group from voting. It is, as they say, a Dead Letter in the Constitution. Lots of constitutions have odd little bits and pieces hanging over from history that are never used. I would enthusiastically support getting rid of this section. However, doing so would not make any practical difference to anybody because it has no current application, but it would require a full referendum to change. It is absurd to use this long-obsolete section to pretend that we have a racist Constitution.

In any event, the cure for racism can never be more racism.

Similarly, it is a mistake to try to insert symbolism into our Constitution. Different national Constitutions serve different purposes according to their distinctive histories and cultures. Some Constitutions do contain stirring aspirational statements: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…

Ours doesn’t. Australians don’t look to their Constitution for symbolic guidance or spiritual meaning. Nor should they. In 1999, in conjunction with the republic referendum, John Howard proposed a preamble to the Constitution which was a generally inoffensive effort to make some statements about our values and included acknowledgement of our Aboriginal history. It was heavily defeated in every state and territory. This was certainly not a vote against Aborigines. It was rather a common sense decision by Australians that they neither needed nor wanted a statement of today’s values inserted into the Constitution.

Our Constitution provides a mechanical rule book for the way government is legally organised in Australia. If you were writing a Constitution today there are many things in it you wouldn’t now include.

But happily, we are not writing a Constitution today. Like every other society, we are a mixture of historical inheritance and contemporary innovation. Generally, the more stable the constitution, the more stable the society. There is a venerable saying in economics that an old tax is a good tax. This means simply that people have already priced-in an old tax, got used to it, factored it into their calculations of value and likely future transactions. There is a real cost to disturbing it.

The same essential wisdom applies even more forcefully to constitutions, especially our Constitution. It has all kinds of inefficiencies but it has certainly provided the legal framework for the development of one of the most liberal and successful societies in the world. Removing any one inefficiency, or adding a whole new dimension, such as a new category of citizenship, risks unbalancing the whole enterprise with unknowable effects.

Perils of rewriting the Constitution

Writing a new Constitution is dreadfully fraught because our knowledge of any new Constitution would be so limited. We would not have, with a new Constitution, the benefit of the historical experience of how it would be interpreted, which we have with an old constitution. This is true too with a new clause in the Constitution.

Nobody has the slightest idea what the High Court, with its tradition of judicial activism and creative interpretations, would do with a Constitutional clause which establishes a Voice. Therefore it’s right to be worried about the unintended practical consequences of messing with the Constitution in this way. This is both a liberal and a conservative objection to the Voice. Above all, this caution, this reluctance about unnecessary and unpredictable change, embodies the virtue of prudence, which should be the virtue which guides all other virtues.

Even in concept, the Voice seems malleable and protean, just as its interpretation by the High Court would likely be. At one stage the justification for the Voice was that Aborigines would at last have a right to have a say about legislation which is about them (as though that does not exist in the current arrangements). Then the idea was that the Voice would allow Aborigines to have a say on legislation which merely affected them.

Of course that is really all legislation. What general provision of any legislation would affect all Australians but somehow or other not affect Aborigines? And why would we assume the Voice, with a very uncertain electoral roll, would accurately reflect Aboriginal opinion? Then the proposition became more general that the Voice could advise parliament, and advise the executive Government, on anything it liked. I’m all for free expression and freedom of opinion.

Any Australian can advise any arm of government on anything. But the power and blocking capacity of a constitutionally enshrined elective body with unspecified but guaranteed consultative powers is unprecedented, unnatural in our Constitution, and completely unpredictable in effect.

Although it would not have the powers of a House of Parliament, it certainly does have the potential to act as a third chamber of parliament by reviewing and delaying and affecting absolutely anything it wants. That can easily take you into the realm of shared sovereignty, or divided sovereignty, or co-sovereignty. And any project like that, which is available to only one race, is inherently racist and contradicts the most basic principle of non-discrimination at the heart of liberalism.

Australia’s existing consultation channels

There is nothing like the Voice in the United States or Canada. Many different societies have many different methods of consulting and assisting their indigenous communities. The United States has treaties with individual Indian tribes, for example. But it does not have a nationally elected, advisory chamber for which only Indian Americans, or only African Americans, can vote and which has compulsory rights of consultation for any law passed by Congress.

Australia too has countless methods of consultation and engagement with Aboriginal citizens. Local consultation, much more than a national Voice, is crucial in trying to form effective policy. There are many regional Land Councils, traditional land owners’ bodies, countless government funded service delivery and community consultation bodies and forums and other Aboriginal groups and consultative bodies seemingly without end. It is true that all this consultation has not produced perfectly effective policy. Nor is there the slightest likelihood that the Voice would do so. As I write, there are 11 Aboriginal members of federal parliament. They are not there just to represent Aborigines. They represent all Australians in their electorates, or if senators, in their states or territories. But they certainly bring to the high table of decision making their Aboriginal histories, sensibilities and consciousness.

Moreover we live in a society abundantly rich in recognition of Aboriginal heritage and presence, both in formal rituals and in popular culture. Throughout the 1980s and 90s I often wrote about the under representation of Asian Australians in popular culture, especially TV drama and comedy, and feature films. It is probably still the case that Asian-Australians are under-represented in popular culture. I certainly don’t want this deficiency remedied by constitutional amendment.

But the Aboriginal presence in our popular culture is now happily very widespread. There are TV series like Redfern Now, Mystery Road, Total Control and many others which featured Aboriginal lead actors in stories about Aboriginal characters. More general TV series like Offspring, Summer Love, The Twelve, and many others featured Aboriginal characters among other Australians. Many Australian films explore Aboriginal stories and characters, so do many Australian novels. This is all a good thing, much to be celebrated. It didn’t require a constitutional amendment and it is more like the way culture should play out. But it is certainly evidence of broad awareness and even celebration of the Aboriginal dimension of Australian life.

This is true at more formal and official levels. When I started first in political activism, then in journalism, more than 40 years ago, it was common that civic functions might start with a prayer, and a luncheon might start with someone saying grace. Those customs are unheard of now, except in formally religious settings. But every domestic air flight I take acknowledges the traditional owners/custodians of the land and their elders past, present and to come. So does every official and semi-official function I attend.

You can even make the case that this is all a bit overdone. One group of Australians having to constantly pay tribute to another group of Australians seems to strike against the easy informality and egalitarianism which characterise Australian culture at its best. But you cannot possibly argue that there is a lack of recognition or acknowledgement of Aboriginal Australia.

Similarly major football codes have indigenous rounds. A huge chunk of Australian territory is controlled by Aboriginal agencies as a result of Native Title decisions. Aboriginal points of view and motifs figure heavily in our education system. My eight-year-old granddaughter tells me that her class studied the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788 from the point of view of Aborigines who saw them land. Racial discrimination of any kind is illegal in Australia.

This is mostly good stuff, so long as the balance of reality is maintained in our education system. But it cannot possibly be consistent with the proposition that there is a yearning emptiness in Australia where Aboriginal recognition should be. That’s just plainly not true. Yet it is the fraudulent emotional message of many advocates of the Voice.

Pro-Voice propaganda and identity politics

This brings us to the emotional manipulation and dishonesty — often enough unconscious dishonesty — of much pro-Voice propaganda. Overwrought and highly emotional prose is produced — if you do not pass the Voice, Aboriginal souls will be broken. It is implied or claimed that the only reason the Voice could be rejected is a hard hearted hostility to, or fear of, Aborigines. If you believe that Aboriginal parents love their children, then you must support the Voice.

These arguments are ridiculous and lack proportion, logic or common sense. When Voice advocates have tried to talk me into supporting it — and I appreciate their kind efforts to do so — they have presented it as a moral choice. If only I had the moral generosity to move beyond my narrow rejection and support the Voice, they argue, that would show a deeper, better moral character on my part. But if I reject the Voice this is evidence of hostility, if not downright racism. This is just ridiculous and in its emotional transaction, if not its methodology, has more to do with a Chinese communist re-education session than normal rational argument.

An issue on which people of perfect goodwill can conscientiously disagree is transformed into a turbo-charged emotional test of moral decency. I think a race-based elective body embedded formally in the Constitution is a bad idea, for all the reasons I’ve outlined in this essay. That doesn’t make me a bad person, nor does it make me a good person. It’s a fundamental category error to assign moral virtue to one side of such an argument and moral degeneracy to the other side.

Yet that is how so much of the discourse around the Voice takes place. I think the idea of a race based body in the Constitution is such a bad idea that it wouldn’t withstand a robust and searching debate. But the cultural and political powers that be are determined that there never will be such a debate.

This is a further clue that what we are really dealing with is a tragic manifestation of the rise and at least temporary triumph of identity politics. There is no more destructive ideological pathology in Western culture today than identity politics.

Part of its dysfunction comes from investing vastly too much human meaning into political causes. A few years ago I asked the former Labor leader, Kim Beazley, if I could interview him for a book I was writing on Christianity. He finally agreed, but with great reluctance. “Mate,” Beazley told me, “my politics is not my religion. It’s not a sin to disagree with my politics. And I don’t want to stand in the way of another man’s experience of the Cross.”

Although I ultimately prevailed on Beazley to proceed with the interview, there was great wisdom in his reluctance, because it showed that he understood the distinction between the deepest questions of human meaning, and mere political disagreement. Few Australians could possibly have invested their full effort more wholeheartedly into policy and politics than did Beazley. But that doesn’t mean that he thinks the ultimate, existential meaning and purpose of life is contained in politics. Tragically, as our society and culture is abandoning religious belief it is investing a febrile, pseudo-religious intensity into every passing ideological debate. That’s why so few of these issues are ever really debated. The imperative is to join the Red Guards style shouting sessions of hysterical unanimity, not to subject radical propositions to serious scrutiny.

We live, notoriously, in a postmodern age. The French sociologist, Jean Baudrillard, argued that postmodernism particularly lacks five qualities: depth, coherence, meaning, authenticity and originality. Postmodernism is also characterised by fluidity, in contrast to stability.

Identity politics is quintessentially a postmodern movement, rejecting objective truth, genuine human free will, and any historical narrative which does not serve the ideological purpose of the moment. One of the best treatments of identity politics comes in Douglas Murray’s The Madness of Crowds. In case after unarguable case, with detail simultaneously compelling, hilarious and depressing, Murray charts the underlying features of this ideological illness.

First, the demands of identity politics are endless and can never be satisfied. Second, the views that anyone expresses are assessed not on their merits but on the basis of their racial identity, or some other element of identity politics such as gender or sexual orientation, or their absolute conformity to whatever is the orthodoxy of the moment in identity politics. Third, disagreement, no matter how measured, mild and rational, is regarded as a sign of malevolence and racism.

This is particularly the case if the dissenter defends the traditional liberal view that race should play no part in constitutional rights or legal standing. Because the whole “white power structure” is defined as rotten to the core, and rotten in every way, inherently and inescapably oppressive in all its guises, any such argument is dismissed as serving the power interests of the white power structure and therefore expressing racism.

Thus a white male can only be considered to be acting morally, or ethically, in those moments when he is actually physically involved in denouncing white privilege. Even that’s not guaranteed. Let me hasten to say I’m not seeking any particular sympathy for white males here. But if you make everything about identity politics, then ultimately everybody wants a share of identity politics. White identity politics is part of the Donald Trump phenomenon in the United States. Lots of folks don’t feel they are part of a corrupt white power structure, but if everything is identity politics, then you will force others into retaliatory identity politics. This way madness lies.

Further, given that the existence of contemporary society allegedly involves the ongoing racist oppression of minorities, especially intersectionally, and that this could only be remedied by comprehensive and ongoing revolution in social, economic and racial structures, then the need to continuously apologise, and forever offer reparations, on a racial basis, means that nothing, no set of measures that any democratic society could reasonably embrace, is ever enough. Thus much of identity politics becomes performative and ritualised, and grievously, drearily sterile, an enemy of rational thought and normal human feeling.

Identity politics is forever. It seeks not to solve a problem or settle an injustice but rather to forever stoke the fires of anger, new anger on top of old anger, new slights to be found in what was once courteous and civil behaviour. Identity politics is of its essence performative. It creates and extends offence, it is forever on the lookout for new occasions of anger, new points of conflict and offence.

Thus, as well as a Voice we are meant to embrace a Treaty and then truth telling. I certainly believe in truth telling and we have that now, if by truth telling we mean the inclusion of Aboriginal points of view, throughout our history studies at every level. Indeed sometimes the pendulum has swung so far the other way that we have new forms of avoiding the truth, but not in the old racist manner. What any decent liberal is extremely wary about is an activist government institution bashing out propaganda.

As to a Treaty, surely John Howard is right that a nation cannot sensibly have a treaty with itself. The idea of an internal formal treaty undermines the legitimacy of the state and repudiates the sufficiency of parliamentary democracy and equal citizenship in civic status.

Finally, there is the idea that Aborigines are special and therefore should get special recognition and rights. A Voice is anti-liberal and anti-democratic because it means most Australians will get to vote only for state and federal parliaments, but Aborigines will get to vote for state and federal parliaments and for the Voice. This also implies, by the way, the truly ghastly task of governments having to determine voters’, and candidates’, racial status to ensure they are eligible to vote and stand for the Voice. This is truly an appalling place for state power to end up, adjudicating people’s racial make up for the purposes of determining civic status. As I type these words I can scarcely believe that my country is contemplating going down such an absurd path. Truly one recalls George Orwell’s remark that to believe some things you have to be an intellectual, no normal person would be so foolish.

Here too is the other anti-human element of the Voice. To tell Aborigines that they are special is to tell them that they are different, inherently different in an essential way from other Australians. This is a grisly triumph of identity politics.

In truth all human beings are special, but not because of racial background. They all have their mystical connections to family or faith or community or land. Each human being is truly mystical, a singular creation, a work of God’s art. No person has a greater depth or virtue of mystery because of their ancestry. The extreme version of blood and soil, often representing an overwrought romanticism, has been the cause of great misery in human history. The state should leave us alone in our deepest identities, which can flourish best in human freedom. There is no reason to privilege one category of people over another. That was a key mistake of the past and one of liberalism’s great triumphs was to undo that mistake.

The greatest rejection of identity politics of all is to be found in Martin Luther King’s I Have a Dream civil rights speech of 1963. Nothing could be further from the moral confusion and rhetorical absolutism of today’s identity politics. King did not ask for a special place in the American Constitution for African Americans because of the historic crime of slavery. His argument was far more subtle and powerful. He asked for America to live up to the universalist promise of its founding documents, of its liberalism. He wanted to cash the constitutional cheque America gave its citizens. He stated his key demand: “There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights.”

Citizenship rights. That was the sum of King’s requirements and those rights, in his view, could lead to a brotherhood across the races. He wanted American institutions to be fully open to African Americans in conformity with a colour blind constitution, a colour blind liberalism. He dreamed of a society in which people were judged by the content of their character, not by the colour of their skin. King’s appeal was to the inherent virtues of liberalism, recognising that those virtues had not been properly lived out in America. The Voice, in contrast, appeals to an at least partial negation of liberalism on the basis of the belief that liberalism can never work sufficiently well for Aborigines.

It is certainly true that every human being can carry multiple identities. I am an Australian. I am also a husband, a father, a grandfather, a journalist, a (very poor) Christian, a man of Irish background, a son of Sydney’s western suburbs, and an NRL Bulldogs supporter. These are all essential elements of my identity. But I don’t want the state, much less the Constitution, to take civic notice of any of these elements of my identity other than that I am an Australian citizen. There is no need to have specific identities beyond citizenship recognised in the Constitution. There is no benefit to it, but there is great danger in it. Our Constitution does not even mention citizens as such. It refers instead to British subjects. But as Australia became fully independent from Britain, the status of citizen was the full and only status that any Australian required.

Conclusion

A liberal society in some senses is always a credal society. If you sign up to the nation’s creed — which may simply mean that you agree to live by its rules and laws and to live in amity with your neighbours — then you can be part of that society. Illiberal societies on the other hand define your status in many other ways — connection to the royal house, your blood and ethnicity, or any of a thousand other destructive identity tests.

Beyond the formal creed of a liberal society, there is always an informal creed as well. In Australia’s case this informal creed typically includes a fair go, mateship or solidarity, openness to newcomers, effort on behalf of yourself and on behalf of society, common sense, common decency. Efforts to capture this informal creed in a formal statement of values or beliefs generally meet with failure, partly because Australians are sensibly distrustful of abstract nouns, and partly because, as a living tradition, the informal creed embraces endless incremental adjustments, changes in emphasis. This normal give and take has no overt presence in the Constitution, which simply provides the structure in which the informal creed is worked out every day by the small battalions of society, and by the millions of inter-actions of individual citizens.

I have hated racism all my life. And I have hated it passionately. A person’s race is the least interesting thing about them. It doesn’t tell me whether they are good or bad or what mixture of both, whether they are sympathetic or hostile, whether they will be a lifelong friend or a passing acquaintance or something else. Opposing the Voice is not about a lack of acceptance or esteem or love of Aborigines. It is about valuing equality of citizenship. For the Constitution to divide Australians on the basis of race is wrong at every level, when we can all be friends and citizens together, with no vertical relationships, all of us instead looking eye to eye, in solidarity and engagement and good humour, with perhaps the trace of a smile.