This paper outlines the barriers to millennial entrepreneurship and proposes solutions for younger generations to undertake entrepreneurial activity.

Why millennials are scared off entrepreneurship: Introduction

Entrepreneurial activity is an essential element of a vibrant economy. It is widely regarded as a determinant of economic growth, and a contributor towards long-term better living standards through the introduction of new and commercially viable ways of producing goods and services. The future economy needs more entrepreneurs; basically, more people with novel ideas, and who are attuned to discovering new ways of providing economic value both for Australians and those abroad.

This same economy needs the diversification that economic entrepreneurship can provide to facilitate new industries and provide future generations with both interesting and satisfying careers. Future governments will need robust private sector activity to provide a revenue base, but that is secondary to the ultimate motivation of elevating entrepreneurship as an exciting pathway for individualised means of accomplishment and flourishing.

Entrepreneurship requires initiative, determination and capital, as well as the courage to take risks — and even embrace failure as stepping stone to a successful venture. However, entrepreneurial activity among younger cohorts is on the wane in Australia, even pre-Covid, and below the average levels of other advanced economies — a situation not assisted by poor government regulation and a lack of incentives.

This policy paper positions its inquiry into the condition of Australian entrepreneurship from an intergenerational perspective. To be clear, this positioning is not limited to what is sometimes described as ‘intergenerational’ (or ‘transgenerational’) entrepreneurship — which pertains to entrepreneurial activity across successive generations. The concern here is regarding the continuance of and, indeed, increasing entrepreneurial prevalence over time, and by whomever wishes to partake in entrepreneurial conduct.

It is readily acknowledged that academic and popular commentary has spawned an array of entrepreneurship concepts. For example, social entrepreneurship appears to have registered a degree of interest among young Australians.1 This paper is focused upon economic (productive) entrepreneurship undertaken by young people within market contexts, and that encompasses the establishment of new commercial enterprises (including sole trading opportunities). Entrepreneurship in this vein is to be sharply contrasted against political (unproductive) entrepreneurship that refers to lobbying and similar petitioning for special-interest favours from government.2 To the greatest extent practicable, this paper will restrict attention to youth entrepreneurship, but general entrepreneurial activity will also be discussed. Furthermore, it is likely that any policies seen as facilitative of youth entrepreneurship will be broadly applicable to other demographic cohorts.

The structure of the policy paper is as follows. The next section will provide a statistical overview of trends in Australian youth entrepreneurialism including, where available, trends over time and international comparisons. This will be followed by a discussion of key policy principles that are identified as having the potential to increase future entrepreneurship rates in Australia. The conclusion provides a brief synopsis of key arguments outlined in this paper.

Profiling Australian youth entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is a dynamic activity involving novelty and surprise. Entrepreneurship is also multidimensional, operating across space and time in variable cultural and institutional contexts, as well as involving an impressive array of individuals of diverse backgrounds and skills. It is difficult to empirically capture this phenomenon, with analysts typically resorting to proxy statistical measures for entrepreneurial activity. It should also be noted that recent events, namely the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns, will affect the comparability of such proxy measures over time. To contemplate the intergenerational dimension of entrepreneurship, it is useful to consider recent trends drawing upon a suite of available information.

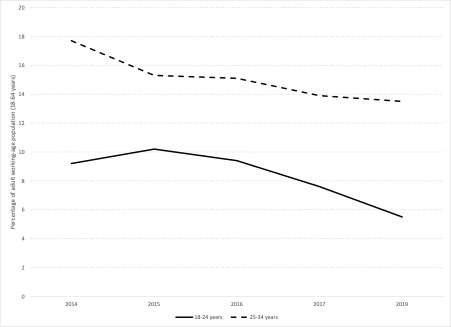

A widely used proxy measure for entrepreneurship is the extent to which demographic cohorts start and run new businesses, typically on a micro or small scale. According to the Australian 2019 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), 5.5 per cent of surveyed 18-24-year-olds in 2019 were involved in the process of starting up a business, or who have started their business less than 3.5 years before being surveyed.3 This represented a fall from 9.2 per cent in 2014, and 10.2 per cent in 2015. The same figure for 24-34-year-olds in 2019 was 13.5 per cent, a decline from 17.7 per cent in 2014 and 15.3 per cent in 2015.

Figure 1 presents the results from the GEM report for the two age cohorts reported here. To contextualise, the same report indicates that entrepreneurial activity for Australia as a whole (that is, across all age groups) also declined prior to the pandemic. From 2016 to 2019, total early-stage entrepreneurship rates fell from 14.6 per cent of the working-age adult population to 10.5 per cent.4

Figure 1. Total entrepreneur activity by 18-24- and 25-34-years age cohorts, 2014 to 2019

Note: Total (early-stage) entrepreneurial activity is defined as percentage of adults in the process of starting a business or have commenced a business less than 3.5 years before being surveyed. Survey results for Australia for 2018 were not reported. Source: Adapted from Steffens and Omarova, 2017, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM): 2017/18 Australian National Report, p. 19.

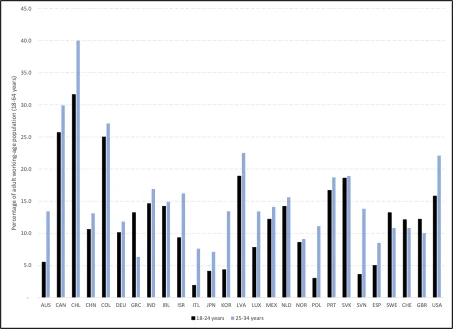

I now turn to international comparisons of youth entrepreneurship rates using the GEM indicator of new business establishment. Pre-pandemic survey data indicated that the prevalence of Australian youth entrepreneurship was below the average of selected advanced economies in 2019.5 The entrepreneurship rate for the 18-24 age bracket in Australia was 5.5 per cent as against 12.3 per cent for the advanced-economy average, while for 25-34-year-olds the Australian entrepreneurship rate was 13.4 per cent compared with 15.5 per cent on average for advanced economies. These results are presented in Figure 2, which also includes the large Asian economies of China and India.

Figure 2. Total entrepreneur activity by 18-24- and 25-34-years age cohorts in selected economies, 2019

Note: Total (early-stage) entrepreneurial activity is defined as percentage of adults in the process of starting a business or have commenced a business less than 3.5 years before being surveyed. Source: Adapted from Bosma, Hill, Ionescu-Somers, Kelly, Levie and Tarnawa. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2019/2020 Global Report, pp. 206-209.

Another proxy measure for entrepreneurship that is commonly used in the literature is self-employment, referring to productive economic activity by a person which does not entail them receiving a consistent salary or wage from an employer.6 Data presented by the World Bank shows that self-employment for all age groups, as a share of the total population, has gradually declined over the past few decades, from about 20 per cent in the early 1990s to about 16.5 per cent in 2019.7 The World Bank does not provide disaggregated data in accordance with age cohort, but longitudinal analysis by the Productivity Commission has indicated that the share of young Australians earning business income has declined over the past two decades.8 The commission observed that younger self-employed workers are more likely to be concentrated in low-paying industries, such as arts and recreation, education, administrative and support services, other services, and agriculture, forestry, and fishing services.

The OECD, in conjunction with GEM, presented additional data outlining the characteristics of businesses operated by self-employed Australian youth (18-30-year-olds).9 Young Australians (6.9 per cent) were found to be less likely than the OECD average in the same age bracket (7.4 per cent) to become involved in business start-up activities. Given their presumed lack of access to capital and finance, certainly when compared against their older counterparts, Australian youth were not likely to be owners of established commercial enterprises (2.1. per cent, compared with OECD average of 2.4 per cent).

The picture emerging so far is one in which Australian youth entrepreneurship rates have been generally lower than that found elsewhere and falling pre-pandemic. Added to this this is the broader observation of persistently high youth unemployment rates in Australia,10 although this tends to be broadly replicated in other countries. When making cross-country comparisons, one should be mindful that lesser accessibility to senior schooling and higher education, and the lack of lucrative entry-level private and public sector employment options, may oblige young people — especially in low- and middle-income countries — to engage in so-called ‘necessity’ entrepreneurship to make a living.11

What is assuredly excluded from the statistical picture constructed above are the many examples of young Australian entrepreneurs successfully breaking the risks and uncertainties surrounding the introduction of products to local, national, and global markets, and reaping the rewards from doing so. Youth entrepreneurial activity is not limited to well-established industries, but is evident in vibrantly innovative fields such as the digital economy (including services and payment platforms, blockchain, robotics, and artificial intelligence).

An array of influences affects the decision by young people to act entrepreneurially (or not). An obvious factor as to why entrepreneurship by this age cohort is not common is that young Australians generally are inclined to continue with further study and training opportunities.12 It is similarly assumed that younger people are less likely to possess sufficient finance and other resources to establish a commercial venture and, relatedly, are unlikely to have enough collateral to successfully apply for business loans (although a few might succeed in obtaining start-up funds from parents, friends, and associates). At any rate, young people may largely seek to work as an employee for an already-existing enterprise over a period to gain the requisite skills, experience, and creditworthiness prior to risking their own capital as an entrepreneur.

The significant presence of a formal economy — as proxied by the high share of corporate profits in national income — suggests that employment options are likely to be attractive for many young people, especially in high-income economies. Recent surveys attest to the employment success rate of both undergraduates and postgraduates, and to the significant share of employment of doctoral graduates by large employers.13

Psychological and cultural considerations also have been diagnosed as influences upon entrepreneurial action. Researchers specialising in economics and sociology have indicated that not only do individuals vary with respect to their alertness to profit opportunities, but broader cultural concerns could shape decisions by young people to opt in favor of (or against) entrepreneurship.14

Some of these include the perceived appropriateness of profit seeking as a mode of economic conduct, and the extent of aversion to failure. About ‘failure norms’, so to speak, comparative studies of entrepreneurial activity in Australia and the U.S. point to appreciable differences in the tolerance of failure amongst entrepreneurs (of all age groups). As noted in one study, “almost half of Australian entrepreneurs agree they see good opportunities but would not start a business for fear it might fail, compared with just over a third of Americans”.15 It is assumed that heightened anxieties regarding career choices on the part of young Australians would, among various margins, generally foster a desire for the perceptually greater security of formal paid employment within a larger corporation or government agency.

The costs of governmental policies are identified, anecdotally and in scholarly research, as an omnipresent deterrent to entrepreneurship. Regulatory burdens are typically among the chief issues cited as hampering entrepreneurial activities.16 In addition to the paperwork and other administrative compliance costs of attending to regulatory edicts, overly prescriptive regulations may have a detrimental effect in terms of delaying the acquisition and use of capital and other valuable resources necessary to activate entrepreneurial activity. Ultimately, regulatory burdens may culminate in a suppression of competitive market processes which, in turn, contribute toward increased prices and restricted supplies.

The economic and financial costs of regulation are not the only challenge; a lack of experience and understanding as to how to navigate administrative and other compliance burdens associated with regulation may be important. A submission to the Productivity Commission inquiry by the Foundation for Young Australians noted that key barriers to business startups or growth by young entrepreneurs included access to finance, human resources issues, and a lack of knowledge about legal systems and regulatory structures.17

There are anecdotal suggestions that a significant share of young Australians have an interest in relocating overseas.18 Updated research on the motivation underlying decisions to leave Australia is required, but past inquiries in this regard suggest that the desire to establish (or expand) a business overseas has been a relatively minor concern. For example, a 2003 report for the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) indicated that less than three per cent of surveyed emigrants moved for this reason.19

By comparison, factors such as ‘better employment opportunities’, ‘professional development’, ‘higher income’, and ‘promotion/career advancement’ each received more than 20 per cent of surveyed reasons given.20 Interestingly, the same CEDA report indicated that 16 per cent of survey respondents cited business opportunities overseas as a reason for being undecided, or not intending, to return to Australia to live.21 In addition to economic and fiscal issues, such as Australia’s lack of international direct tax competitiveness,22 factors such as negative perceptions about Australian social attitudes toward risk or to business activity,23 cost of living differentials, and lifestyle considerations could all come into play in explaining rates of emigration persistence.

The ‘offshoring’ of talent is not necessarily problematic for the Australian economy. There is the likelihood of some Australians returning home, especially to the extent that the diaspora maintains family and professional networks back home. In addition, Australian consumers can enjoy the fruits of entrepreneurial endeavors by its diaspora insofar as goods and services trade barriers remain low. Another factor to bear in mind is that entrepreneurial migrants from all corners of the world may elect to establish their initiatives in Australia, although concerns have been aired, until very recently, about subdued immigration rates since the post-Covid reopening of borders. Putting these considerations aside, if retaining entrepreneurial talent in Australia is considered as policy desideratum it would be important to focus attention upon policies that would better secure gains from productive entrepreneurship undertaken domestically.

Policy principles to promote future generations of entrepreneurship

The Australian economy of the future will need more private entrepreneurship, where today’s youthful startups become the maturing productive powerhouses of tomorrow. Furthermore, the size of commercial enterprises instigated by Australia’s young people need not be limited to small scale, craft firms. In other words, a pro-entrepreneurial economic climate for Australia should empower individuals to scale up their firms as they see fit, depending upon the existence of market opportunities both at home and abroad, availability of capital, appetite for risk, and other relevant factors. It is in the pursuit of this vision of an entrepreneurial Australia that young Australians can join in and play their part in a better future for themselves and for others, through the discovery of new innovations as well as investment, employment, and export opportunities.

Economist William Baumol made the distinction between productive entrepreneurship and unproductive entrepreneurship.24 Productive entrepreneurship, which is the focus of this paper, is advanced when people remain alert to market discoveries that would serve to add value for consumers, and to contribute to the expansion of the economy. By contrast, unproductive entrepreneurship is represented by political discoveries aiming to transfer advantages and privileges (including in economic and financial forms) for those who lobby for them, but which come at the expense of everyone else in society.

The quality of institutional rules is seen to play a crucial role in determining the relative payoffs between productive and unproductive entrepreneurship. An institutional structure that promotes the freedom of individuals to engage in productive entrepreneurship through the market is largely agreed to be an important ingredient for long term material betterment. A 2007 paper by Sobel, Clark, and Lee empirically examined the relationship between levels of economic freedom in OECD countries and entrepreneurship rates, the latter being drawn from the GEM. They indicated that “countries with more economic freedom have a larger amount of productive, private sector entrepreneurial activity. Countries with less economic freedom, and more government interference and regulation, have less.”25 Separate papers published the following year by Christian Bjørnskov and Nicolai Foss, and by Kristina Nyström, made similar conclusions.26

In a 2017 study covering OECD countries over the period 2001 to 2012, it was found that economic freedom was positively associated with opportunity entrepreneurship. Specifically, “a better legal structure and security of property rights and more lenient regulation of credit, labor and business tend to favor entrepreneurship by opportunity”.27 Crucially, the authors identified a negative correlation between economic freedom and necessity entrepreneurship. A 2016 survey of empirical literature by the Montreal Economic Institute concluded that a range of international and national studies affirmed the positive association between entrepreneurship and economic freedom.28

An institutional structure of economic freedom suggests several policy commitments. These include low taxes and modest (and efficient) public spending, which allow individuals to keep more of the returns they gain from their entrepreneurial successes, as well as streamlined regulatory edicts as they impact business formation and ongoing operations.

The generic maintenance of the rule of law also equips people with the legal confidence to try out new economic ventures, without undue fear of expropriation by public officials. Countries with relatively greater economic freedom are presumed to have deeper capital markets, enabling young people (and others in different adult age cohorts) to tap into a vaster array of resources to finance their startups.29 An abundance of human capital investment opportunities in economically freer countries provides educated individuals with an ample skillset to apply their talents entrepreneurially, should they elect to do so.30

The future Australian entrepreneurial economy will also need more flexible labour markets. Numerous predictions have been made that automation and other forms of digital intensity within workplaces is likely to change the occupational structure of the economy, and even to displace certain jobs that presently exist.31 Certain analysts consider that the onset of innovations such as artificial intelligence would not easily displace work opportunities, and the entrepreneurship necessary to catalyse such opportunities, that emphasise interpersonal communication, affective engagement, care, and intensive customer support.32 Complementing this position would be the need to maintain, if not extend, Australia’s relatively liberalised immigration settings to facilitate the entry of skilled, young entrepreneurial talent from around the world over coming years and decades, especially as the country’s population ages.

A pro-entrepreneurial policy is equally informed by the identification of measures that governments should not undertake. This includes the political avoidance of intellectual postures, such as those promulgated by economist Mariana Mazzucato,33 that suggest that politicians somehow possess the ‘entrepreneurial’ capacity for selecting and implementing innovations. As the critics of her position have already indicated,34 the wrongful attribution of entrepreneurial prowess to politicians, whose activities are not exposed to the disciplining market impulses of profit-and-loss mechanisms and inalienable property, is likely to foster a culture of unproductive private sector entrepreneurship via rent-seeking behaviour.

Historical evidence points to the notion that societies dominated by statist directionality over the allocation of resources are unlikely to enjoy positive economic outcomes. Ultimately, the failure of communist and other authoritarian systems that suppress market activity is attributed to the need for economic agents to pander to the political prerogatives of governing elites, rather than to the economic prerogatives of consumers.35 Less dramatic, but no less significant, are those variants of mercantilist industrial policy that attempt to establish entrepreneurial cohorts, or ‘champions’, that can serve the interests of the nation-state in terms of capturing global market shares in strategic industries or sectors. This so-called ‘champions policy’ stance has also been critically scrutinised.36

As has been discussed in this paper, the entrepreneurial function does not assume materialistic characteristics alone. Entrepreneurship is an activity with potentially great rewards but is also conducted under uncertain conditions and circumstances. The way that we talk can influence our choices as to whether to pursue productive entrepreneurial actions, or to ‘play-it-safe’ so to speak, as an employee in an already-established private or public entity. The influence of social and political discourses upon entrepreneurial activities, including personal perceptions of risks and uncertainties associated with entrepreneurship, have been raised in academic literature.37

The Australian GEM 2019 survey report suggests that there is relatively strong support for entrepreneurs, with 60 per cent of respondents agreeing that those successful at starting a new business have a high level of status and respect.38 The same report indicates that almost half of those responding to the GEM survey indicate a fear of failure as a deterrent to starting a business.39 It is here that the more effective communication of economic insight may contribute toward mitigating a perceptually negative attribute of entrepreneurial action.

Criticisms of entrepreneurial failures tend to overlook the insight that in a freer economy individuals would generally have a wider range of remedial options at their disposal (including modifying their initial plans and retrying entrepreneurial activity), not to mention that the failed examples signal to others what economic experiments to modify or avoid. Better communication concerning the range of support mechanisms and practices, including available mentoring networks, to help guide people — especially the young — through the formative period of entrepreneurial activity would also be advisable.

Conclusion: millennial entrepreneurship

Each year thousands of young Australians choose to engage entrepreneurially in the market. Many of them succeed in doing so, as attested by the creation of profitable commercial enterprises and the introduction of new goods, services, processes, and systems. These young entrepreneurs have displayed a remarkable tenacity and resilience in forging their own entrepreneurial pathways, particularly during the period of Covid-19 lockdowns and related business restrictions in 2020-21.

This paper has identified a pre-pandemic slowdown in Australian youth entrepreneurship rates, with below-average entrepreneurship in Australia by those between the ages of 18 and 34 as compared to an average of advanced economies. Future growth and prosperity hinges upon an expansion of productive entrepreneurship over coming years and decades, and so reforms are necessary to reverse the recently reported declines in youth entrepreneurship rates.

Australia’s economic policy trajectory has been heading down the wrong path over recent years, a development which calls for its own reversal. This paper articulates the need for reforms geared to promoting economic freedom, presenting to young people entrepreneurship in a vibrant, growing market as a real, and attractive, option. In the case put forward here, reform will mean that the payoff structure in the economy is incented toward productive entrepreneurship characterised by the seeking of profits in the market. From there, specific policies consistent with adhering to better rules are geared toward increasing the relative rewards attributed to productive entrepreneurship, and deterring the rent seeking, corruption, and privilege-fueled inequalities that come with entrepreneurship of the unproductive kind.

Entrepreneurship is more than just about material incentive to take a risk with the aim of getting ahead. How we refer to entrepreneurial activity in our social and political conversations matter; after all, if all the talk is that entrepreneurship is, for whatever reason, too fraught an exercise then young Australians will likely favour other economic options. Conversations about entrepreneurship and its abundant possibilities are likely to have a profound influence upon the proclivity of future generations to pursue the entrepreneurial route. Therefore, the nature and quality of our discussions about entrepreneurship will have a long-term impact upon Australia’s reputation and achievement as a land of opportunity.

Endnotes

1 Social entrepreneurship may be described as novel efforts to discover potential solutions to social problems, or to create new sources of social value.

2 This important distinction will be revisited later in the paper.

3 Renando, Chad and Char-lee Moyle. 2021. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2019: Australia Report. Brisbane: Australian Centre for Entrepreneurship Research, Queensland University of Technology.

4 Ibid., p. 15.

5 Bosma, Niels, Stephen Hill, Aileen Ionescu-Somers, Donna Kelley, Jonathan Levie and Anna Tarnawa. 2020. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2019/2020 Global Report. London: Global Entrepreneurship Research Association. The OECD-member developed economies in the reported sample were Australia (AUS), Canada (CAN), Chile (CHL), Colombia (COL), Germany (DEU), Greece (GRC), Ireland (IRL), Israel (ISR), Italy (ITA), Japan (JPN), Korea (Republic of) (KOR), Latvia (LVA), Luxembourg (LUX), Mexico (MEX), Netherlands (NLD), Norway (NOR), Poland (POL), Portugal (PRT), Slovak Republic (SVK), Slovenia (SVN), Spain (ESP), Sweden (SWE), Switzerland (CHE), United Kingdom (GBR), and United States (USA). Youth entrepreneurial rates for these countries are illustrated in Figure 2, as are results for China (CHN) and India (IND).

6 A definition of self-employment by the International Labour Organization is of “workers, working on their own account or with one or a few partners or in cooperative, hold the type of jobs … where the remuneration is directly dependent upon the profits derived from the goods and services produced. Self-employed workers include four sub-categories of employers, own-account workers, members of producers’ cooperatives, and contributing family workers.” The source for this quote is provided in the following footnote.

7 Source: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.EMP.SELF.ZS.

8 Productivity Commission. 2021. Why did young people’s incomes decline? Commission Research Paper, Canberra. According to the report, an implication of this trend is that the purported growth of the “gig economy” is likely to be overstated.

9 OECD. 2019. The Missing Entrepreneurs 2019: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship. Paris: OECD Publishing.

10 Carvalho, Patrick. 2015. Youth Unemployment in Australia. CIS Research Report No. 7.

11 Gries, Thomas and Wim Naudé. 2011. “Entrepreneurship and human development: A capability approach.” Journal of Public Economics 95 (3): 216-224; Brewer, Jeremi and Stephen W. Gibson. 2014. Necessity Entrepreneurs: Microenterprise Education and Economic Development. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

12 Productivity Commission. 2015. Business Set-up, Transfer and Closure. Inquiry Report No. 75. Canberra. High rates of educational attainment reinforce the importance of the provision of efficient and high-quality educational services, providing young people with the literacy and numeracy to underpin productive future careers. On key issues affecting the Australian school education sector, see Fahey, Glenn. 2020. Dollars and Sense: Time for Smart Reform of Australian School Funding. Centre for Independent Studies, Research Report No. 40.

13 Social Research Centre. 2022. “2022 Graduate Outcomes Survey – Longitudinal.” https://www.qilt.edu.au/surveys/graduate-outcomes-survey—longitudinal-(gos-l); McCarthy, Paul X., and Maaike Wienk. 2019. “Who are the top PhD employers?” Australian Mathematical Studies Institute and CSIRO Data61, https://amsi.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/advancing_australias_knowledge_economy.pdf.

14 Storr, Virgil Henry and Arielle John. 2011. “The Determinants of Entrepreneurial Alertness and the Characteristics of Successful Entrepreneurs.” Annual Proceedings of the Wealth and Well-Being of Nations 3: 87-107.

15 Scott-Kemmis, Don and Claire McFarland. 2020. “Entrepreneurship in Australia and the United States: Contrasts in attitudes and perceptions, and insights from successful Australian ventures.” University of Sydney, United States Studies Centre, p. 8; also, Ghazavi, Vafa. 2018. “Ava go, ya mug! How Australia can stop fearing failure and embrace the best of American innovation culture.” University of Sydney, United States Studies Centre.

16 An overview of the burdens attributed to Australia’s regulatory settings are described in Tunny, Gene and Ben Scott. 2020. Rationalising Regulation: Helping the economy recover from the corona crisis. Centre for Independent Studies, Analysis Paper No. 14.

17 Foundation for Young Australians. 2015. Backing Young Entrepreneurs: FYA submission to the Productivity Commission Draft Report on Business Set-Up, Transfer and Closure. https://www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/190907/subdr056-business.pdf (accessed 8 June 2022).

18 Recent reports have suggested that in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic a considerable proportion of surveyed young Australians have expressed an intention to live and work overseas. For example, Panagopoulos, Joanna. 2022. “40% of young people are thinking about getting these visas.” The Australian, September 19.

19 Hugo, Graeme, Dianne Rudd and Kevin Harris. 2003. Australia’s Diaspora: Its Size, Nature and Policy Implications. Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA): Sydney.

20 Ibid., p. 44. As discussed in the main text, career opportunities pursued today does not preclude entrepreneurial actions undertaken tomorrow (whether in Australia or overseas).

21 Ibid., p. 53.

22 Bunn, Daniel. 2022. International Tax Competitiveness Index 2022. Washington, DC: Tax Foundation. Overall, Australia is ranked highly on tax competitiveness across the OECD however its ranking is weighed down by its personal and corporate income taxes.

23 For an example of anecdotal statements concerning perceptions of Australian attitudes toward economic risk, see Guest, Kate. 2021. ‘A spoilt brat country’: the Australians overseas who decided not to come home. Guardian Australia, January 1. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/jan/02/a-spoilt-brat-country-the-australians-overseas-who-decided-not-to-come-home

24 Baumol, William J. 1990. “Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive.” Journal of Political Economy 98 (5): 893-921.

25 Sobel, Russell S., J. R. Clark and Dwight R. Lee. 2007. “Freedom, barriers to entry, entrepreneurship, and economic progress.” Review of Austrian Economics 20 (4): 221-236, p. 227.

26 Bjørnskov, Christian and Nicolai J. Foss. 2008. “Economic freedom and entrepreneurial activity: Some cross-country evidence.” Public Choice 134 (3-4): 307-328; Nystrӧm, Kristina. 2008. “The institutions of economic freedom and entrepreneurship: Evidence from panel data.” Public Choice 136 (3-4): 269-282.

27 Angulo-Guerrero, María J., Salvador Pérez-Moreno and Isabel M. Abad-Guerrero. 2017. “How economic freedom affects opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship in the OECD countries.” Journal of Business Research 73: 30-37 p. 33.

28 Bédard, Mathieu. 2016. Entrepreneurship and economic freedom: Analysis of empirical studies. Montreal, Canada: Montreal Economic Institute. We do note a study presenting an alternative conclusion of statistically insignificant associations between economic freedom and entrepreneurship (Ridderstedt, Ivan. 2014. “Economic freedom and entrepreneurship: Conflicting evidence – An empirical analysis based on the 2011 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Report.” Sӧdertӧrn University, Bachelor thesis.) Our assessment of the weight of peer-review evidence is that economic freedom tends to have a positive, statistically significant correlation with entrepreneurial activity.

29 Hafer, R. W. 2013. “Economic freedom and financial development: International evidence.” Cato Journal 33 (1): 111-126.

30 King, Elizabeth M., Claudio Montenegro and Peter F. Orazem. 2012. “Economic freedom, human rights, and the returns to human capital: An evaluation of the Schultz hypothesis.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 61 (1): 39-72; Feldmann, Horst. 2017. “Economic freedom and human capital investment.” Journal of Institutional Economics 13 (2): 421-445.

31 Davidson, John. 2020. “The robots are coming: 2.7 million Aussie jobs to disappear.” Australian Financial Review, March 11.

32 Lee, Kai-Fu, and Chen Quifan. 2022. “What AI cannot do.” Big Think, January 19. https://bigthink.com/the-future/what-ai-cannot-do

33 Mazzucato, Mariana. 2013. The entrepreneurial state: Debunking public vs. private sector myths, London: Anthem Press. Mazzucato’s ideas were approvingly raised in Australian Treasurer Jim Chalmer’s Monthly February 2023 essay calling for a “values-based capitalism.”

34 McCloskey, Deirdre Nansen, and Alberto Mingardi. 2020. The Myth of the Entrepreneurial State. Great Barrington, MA: American Institute for Economic Research; Wennberg, Karl, and Christian Sandstrӧm. 2022. Questioning the Entrepreneurial State: Status-Quo, Pitfalls, and the Need for a Credible Innovation Policy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

35 Lavoie, Don [1985] 2016. National Economic Planning: What Is Left? Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

36 Note the examples listed in Lincicome, Scott and Huan Zu. 2021. Questioning Industrial Policy: Why Government Manufacturing Plans Are Ineffective and Unnecessary. Cato Institute. https://www.cato.org/white-paper/questioning-industrial-policy. Bryan Cheang presents a nuanced critical position with regards to Singaporean industry policy, with the application of such a policy shown to reduce innovation, productivity growth, and private entrepreneurship. Cheang, Bryan. 2022. “What Can Industrial Policy Do? Evidence from Singapore.” Review of Austrian Economics, doi: 10.1007/s11138-022-00589-6.

37 Lavoie, Don, and Emily Chamlee-Wright. 2000. Culture and Enterprise: The Development, Representation and Morality of Business. Washington DC: Cato Institute; McCloskey, Deirdre N. 2010. Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can’t Explain the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. A recent study of the effects of ideological rhetoric on entrepreneurship, and the role of institutions in moderating such effects, see Bennett, Daniel L., Christopher Boudreaux and Boris Nikolaev. 2022. “Populist discourse and entrepreneurship: The role of political ideology and institutions.” Journal of International Business Studies, doi: 10.1057/s41267-022-00515-9.

38 Renando and Moyle, op. cit., p. 13. It is noted that the level of agreement with the statement that successful entrepreneurship enjoys a high level of status and respect declined by about ten percentage points from 2015 and 2016 to 2019.

39 Ibid., p. 11.

ALSO READ: Generation Next: Unleashing youth aspiration and upward mobility