Energy market bodies’ blind faith in solar paradise

Rooftop solar uptake depends on high financial returns

Federal government rebates made rooftop solar more affordable

State governments implemented generous feed-in tariffs to accelerate adoption

Measuring the return on investment for rooftop solar in New South Wales

Financial returns drive rooftop solar adoption in New South Wales

How much does rooftop solar save the grid?

Rooftop solar and the distribution network

Rooftop solar does not save distribution costs through demand reduction

Rooftop solar increases distribution costs by introducing instability

Rooftop solar owners are earning outsized bill savings

Rooftop solar owners are being cross-subsidised by non-solar customers

Current tariff structures enable cross-subsidies at the expense of consumers without rooftop solar

Rooftop solar: reverse Robin Hood

Export charges will not end cross-subsidies

Two-way export tariffs introduced, but not everywhere

Rooftop solar owners continue to earn outsized savings under two-way export tariffs

Batteries will not lead us to paradise

State government battery subsidies have largely failed to increase uptake

Batteries are unlikely to save distribution costs

Ending the cross-subsidies: difficult but necessary

Large fixed component and small variable critical peak charge

Large fixed component and small variable critical peak charge with SMS

Fixed charge only based on land or property value

Fixed charge only based on household income

Fixed charge only with limited or unlimited peak demand options

Fixed charge based on residence size and type and household size

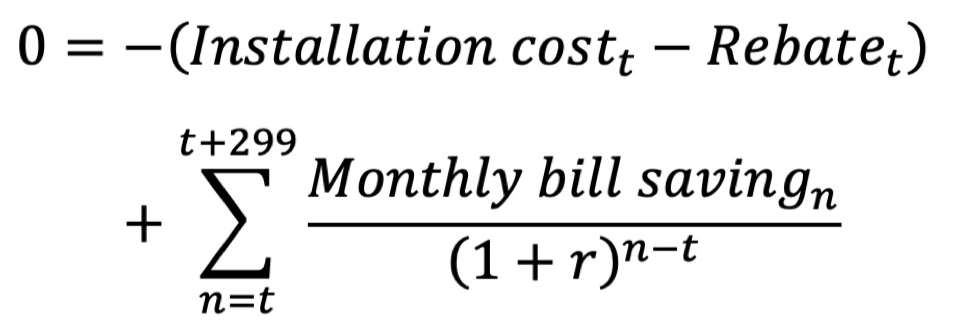

Payback period, 25-year ROI, and 25-year IRR for rooftop solar

System savings from rooftop solar

Outsized savings for NEM customers under current tariffs

Outsized savings for Ausgrid customers with and without export tariffs.

Executive Summary

Rooftop solar has been lauded by energy market bodies, policymakers, the media and environmental groups as a great way to lower bills, help the environment and help the grid. But while rooftop solar may have lowered bills for homeowners able to install it, it has done so by increasing bills for everyone else. As more consumers respond to distorted price signals by installing rooftop solar, the paradise that has been promised is being lost.

Over the past 15 years, rooftop solar has enjoyed rapid growth in Australia due to its historically high return on investment for households. In 2011, government rebates covered more than 75% of installation costs for a 1.5 kW system, coinciding with the highest installation rate to date. Although direct government subsidies have declined in recent years, rooftop solar systems still offer households substantial financial benefits. In New South Wales (NSW), this amounts to a return on investment of well over 200% and a payback period of less than 6.5 years. However, these financial returns do not reflect the value that rooftop solar provides the grid.

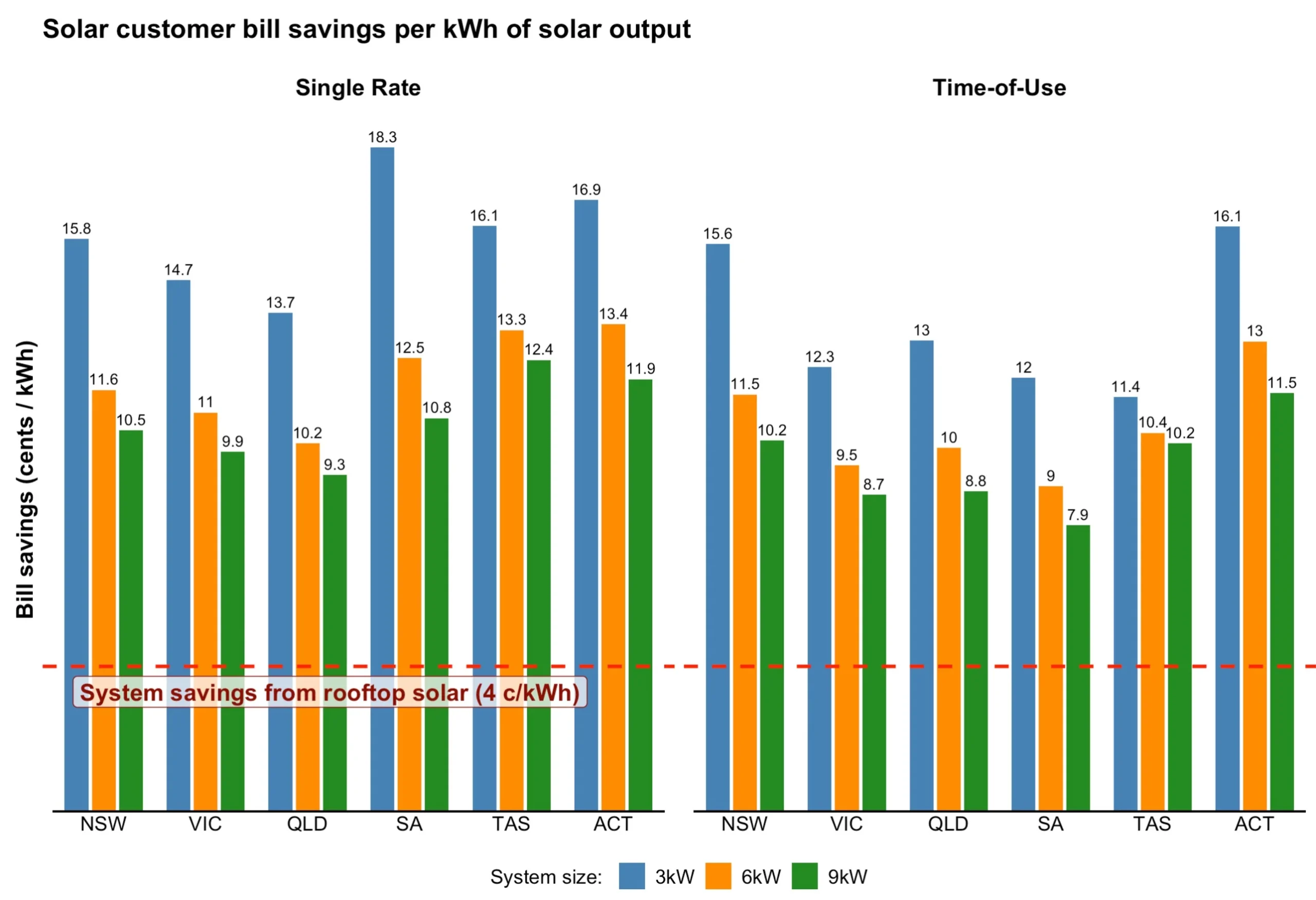

CIS analysis suggests rooftop solar generation saves the electricity grid at most only 4c/kWh in averted variable operating and fuel costs for coal and gas plants. This is before including any additional network upgrade costs that arise when the grid is stressed by a glut of rooftop solar output in the middle of the day; so actual system savings may be much lower.

Using conservative assumptions, the CIS estimates rooftop solar owners in National Electricity Market (NEM) states are currently receiving bill savings of 8–18c/kWh for their solar generation, including both exports and self-consumption. This means rooftop solar owners are receiving savings 2–4.5 times higher than the value their solar generation is providing the grid.

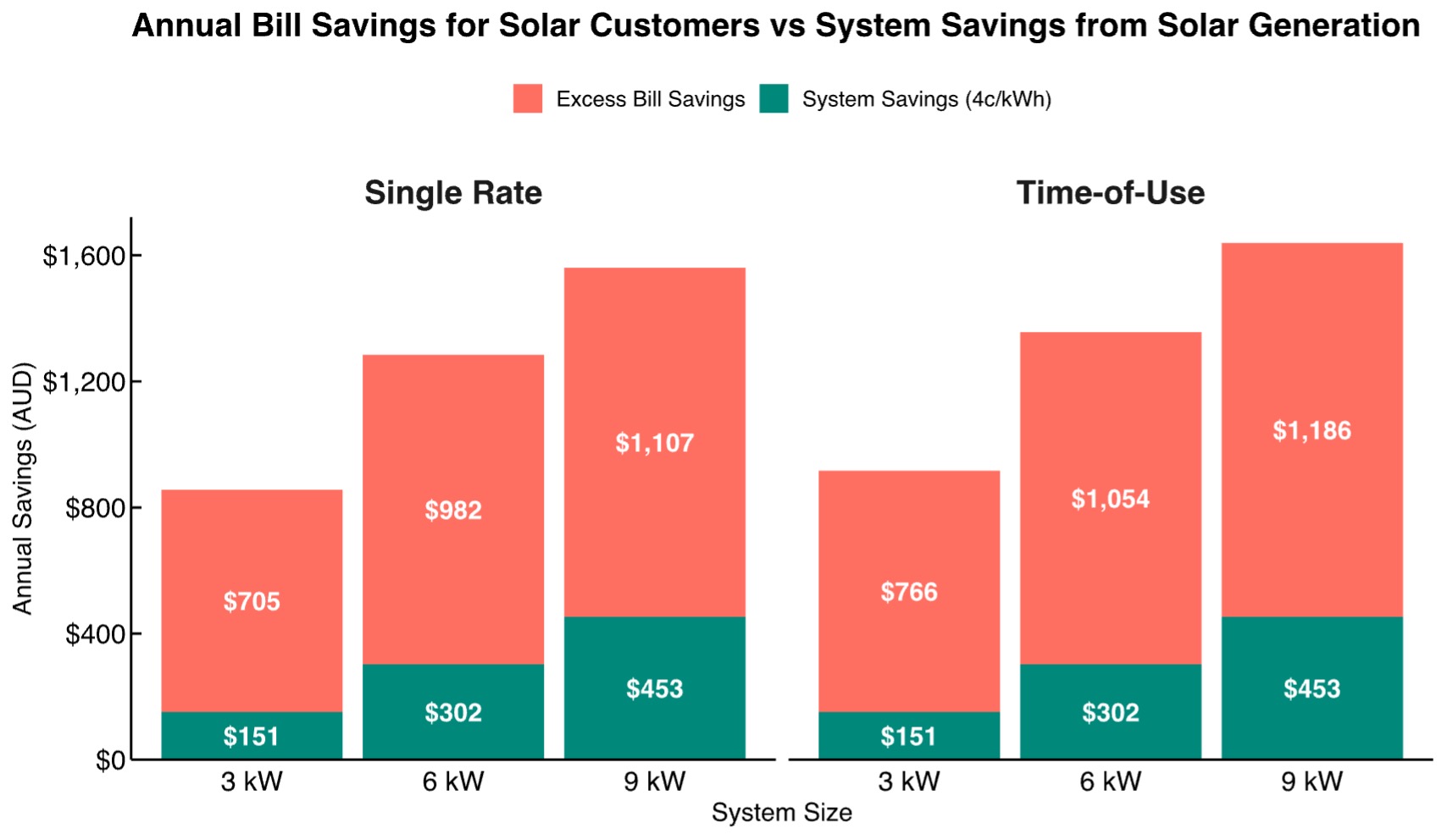

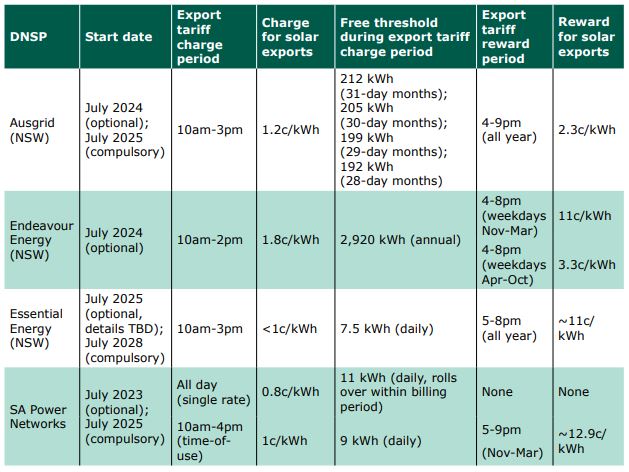

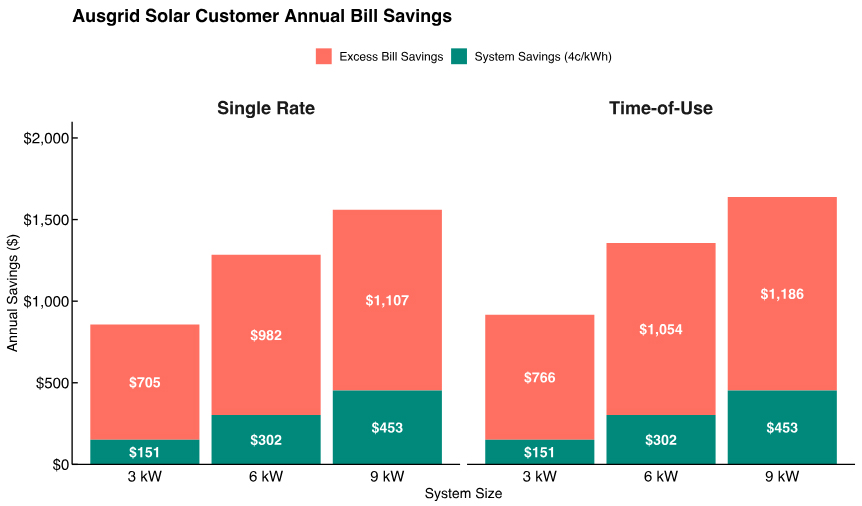

In the Ausgrid network in NSW, solar customers are earning, on average, $705 to $1,186 more than the cost savings their generation provides the grid (Figure 1). These outsized savings have arisen because solar customers are paying much less than non-solar customers for their use of the network, despite imposing similar or even higher costs on the network. Distribution Network Service Providers (DNSPs) must recoup this lost revenue by charging other customers more, which creates substantial cross-subsidies from those who do not own rooftop solar to those who do. Rooftop solar owners tend to be older and wealthy enough to own a house, meaning those who are less wealthy — particularly young renters and apartment dwellers — are effectively paying part of their energy bills. This ‘reverse Robin Hood’ — taking from the poor to give to the rich — is increasing bill stress for the most vulnerable consumers.

To listen to this research on the go, subscribe on your favourite platform: Apple, Spotify, Amazon, iHeartRadio or PlayerFM.

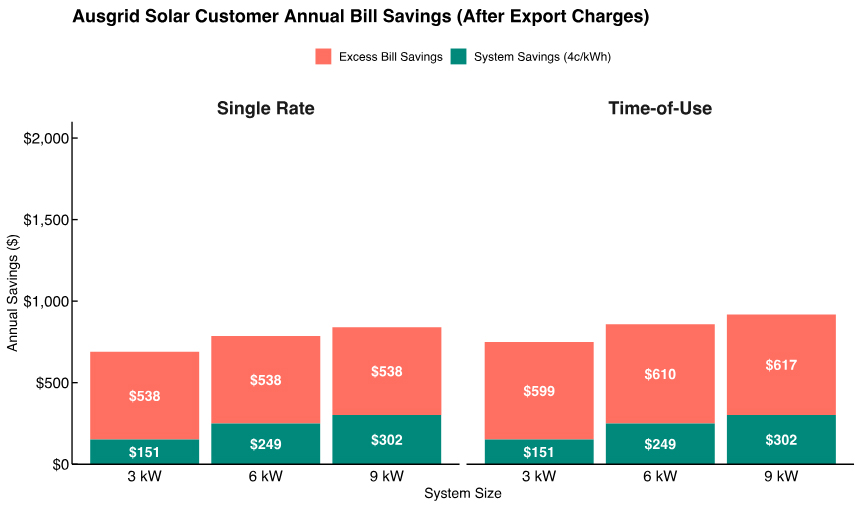

Figure 1. Bill savings for Ausgrid rooftop solar customers on both single rate and time-of-use tariffs exceed electricity system savings from rooftop solar generation (4c/kWh) regardless of solar system size

The outsized savings rooftop solar owners receive arise because of the way network costs are passed onto consumers. DNSPs recoup 60-75% of their mostly fixed costs through variable network charges or ‘tariffs’, which retailers typically pass on to consumers as a component of variable usage rates. But rooftop solar owners are often able to avoid paying these usage rates — and the network charges they contain — through self-consuming their solar output during the day.

Rooftop solar owners also benefit from rewards for their exports. Some DNSPs in NSW have introduced new two-way export tariffs that charge for exports during peak solar hours, which would help to reduce the earnings customers receive from exporting to the grid if passed through by retailers. Nevertheless, most retailers currently provide rewards well above 4c/kWh for exports, adding to the outsized savings rooftop solar owners receive from averted usage. Even if retailers do pass through two-way export tariffs to customers, NSW solar customers will continue to receive substantial outsized savings of $538 to $617 more than they should be, mostly through continuing to avoid variable usage rates by self-consuming solar output.

Recent attempts by the energy market bodies to make network tariffs more cost-reflective have fallen short, as they have involved moving customers to time-of-use or demand tariffs. These tariff structures do not send consumers a price signal based on the main driver of network upgrade costs: forecast critical peak demand, or the highest level of demand in a year or several years. While demand tariffs can reduce cross-subsidies, they are too blunt an instrument to eliminate them. Time-of-use tariffs are much less cost-reflective than demand tariffs. CIS analysis indicates Ausgrid solar customers on time-of-use tariffs earn even greater savings than single-rate solar customers (Figure 1). This suggests the current reform efforts to put single-rate customers on time-of-use tariffs may make cross-subsidies worse in the short term, at least in some distribution networks.

Rooftop solar is unable to provide material savings on distribution network upgrade costs, as these are driven by forecast critical peak demand. DNSPs have quantified apparent reductions in historical critical peak demand from rooftop solar output, but these are not on the spatial or temporal timescales necessary to reduce the need for local grid upgrades. Rooftop solar cannot provide savings from demand reduction, as such reductions are not reliable enough to base forecasts on. Any DNSP that assumes a given level of rooftop solar output during a critical peak demand event risks this not eventuating due to cloud cover, and therefore saves upgrade costs at the expense of increasing the risk of reliability breaches — a false economy. In fact, increasing penetrations of rooftop solar will likely increase the need for upgrades. DNSPs would have to incur currently unknown, but likely substantial, costs to manage the effects of grid stress from minimum demand and a glut of solar exports in the middle of the day. Yet, even without considering these added costs, rooftop solar owners are still being subsidised by those without rooftop solar.

Serious network tariff reform is required to eliminate cross-subsidies for rooftop solar. The most effective way to do this may be to switch to a network tariff structure with a fixed charge based on residence type, with no variable charges. Customers would still face variable charges for the generation component of their bill based on their usage, but network charges would be entirely recovered through the fixed daily charge. This would prevent solar customers from receiving outsized savings from self-consumption. Although it would not be as cost-reflective as charging customers for their contribution to critical peak demand, it may be more feasible to implement. Crucially, a fixed charge would not punish consumers with inflexible energy needs, such as young families, for being unable to reduce their critical peak demand. It would also alleviate bill stress for those without solar by ending solar cross-subsidies.

If cross-subsidies were eliminated, rooftop solar installations would likely plummet, as the vast majority of consumers who invest in rooftop solar do so because it benefits them financially. If rooftop solar’s true value to the system were reflected in the bill savings of rooftop solar owners, very few would install new systems or replace existing ones. Given the Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO) Integrated System Plan (ISP) relies on a four-fold increase in rooftop solar by 2050, the question remains as to how this will be achieved without cross-subsidies continuing. This magnitude of increase in rooftop solar installations would mean a shrinking base of non-solar customers would have to subsidise the network costs of a growing cohort of rooftop solar owners. With worsening bill impacts for vulnerable consumers, governments would likely have to step in with greater direct subsidies to ensure the incentives to install rooftop solar continue, further burdening the taxpayer and stoking inflation.

The analysis in this paper mainly concerns rooftop solar owners who do not own batteries. Home batteries are often put forward as the solution to the problems caused by increasingly high penetrations of rooftop solar because they can shift solar generation to periods of peak demand and help reduce stress on the grid. But batteries remain uneconomic for most rooftop solar owners and state government subsidies have thus far failed to provide enough incentive to substantially increase uptake. With battery prices remaining flat for the past six years, there is no guarantee prices will halve in the near future, as commonly assumed. Given home batteries are more than twice the price of grid-scale batteries, incentivising their uptake represents a suboptimal policy that will increase overall system costs, which is reflected in consumer bills. Subsidising home batteries as a solution to our grid’s rooftop solar woes is simply throwing good money after bad.

Rooftop solar provides little value to the grid. It was never going to lead Australia to an energy paradise. Hence, we should end the cross-subsidies driving rooftop solar uptake and the inevitable bill stress it causes, particularly for the most vulnerable consumers.

1. Introduction

For years, Australians have been promised an energy paradise powered by rooftop solar. As Energy Minister Chris Bowen puts it:

When it comes to powering our homes, Australians know nothing will beat our sun. We are lucky to call the sunniest continent on earth home, which means we’ve got access to the cheapest and cleanest renewable energy resource at our fingertips. Aussie homeowners know rooftop solar is a no-brainer when it comes to bringing down bills, which is why we have been installing about 300,000 rooftop systems a year and there is no sign of that slowing down.[1]

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has similarly painted a rosy picture:

High-efficiency rooftop solar is absolutely central to reducing our national emissions, rebuilding our national energy grid and taking pressure off family budgets… It’s a way of doing the right thing by the environment, while cutting your power bill…Rooftop solar reduces household bills by up to 57 per cent… This also takes pressure off the national grid, when rooftop solar output goes up, wholesale demand — and wholesale prices — go down. This is where your hard work serves Australia’s national interest.[2]

This vision of a sun-drenched nation powered by an ever-growing sea of solar panels may seem like a dream come true. However, recent events have revealed serious flaws in this narrative of solar-powered prosperity.

Rooftop solar was of little help when NSW faced peak electricity demand during a sub-40°C heatwave just before summer 2024.[3] The only way the state avoided blackouts was by asking — sometimes even paying — residents and businesses to reduce their electricity use in the evening.[4] More recently, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) requested that emergency powers switch off rooftop solar systems. This suggests that, rather than being a benefit to the grid, the rapid expansion of rooftop solar is posing a threat to the grid’s stability and security.[5]

Yet, politicians and policymakers continue to promote rooftop solar as an economic and environmental win-win. The Prime Minister has gone so far as to claim that just as rooftop solar “makes economic sense” for individual households, large-scale solar “makes sense” for the national economy.[6] Albanese has tied Labor’s 82% renewables target for 2030 to lower energy bills, implying that because rooftop solar reduces costs for some households, expanding renewables will lower electricity prices overall.

But this raises a fundamental question: Is rooftop solar truly lowering energy costs for everyone, or simply shifting the burden onto those without it?

This paper examines how rooftop solar, rather than delivering the universal economic and environmental benefits often promised, has created financial distortions in Australia’s energy market. These distortions have led to inequitable cost-shifting, where non-solar households bear the financial burden of subsidising solar owners. While rooftop solar customers enjoy significant savings, the wider electricity system is grappling with rising costs and grid instability.

To understand this dynamic, the paper first explores how government incentives and tariff structures have fuelled rooftop solar adoption, creating substantial financial returns for solar owners while increasing costs for non-solar consumers. It then examines the impact of rooftop solar on the electricity grid, revealing that while it reduces daytime demand, it does not alleviate peak stress and may, in fact, exacerbate system instability. Finally, the paper assesses proposed reforms, such as two-way export tariffs and battery adoption, and whether they can address the inequities and technical challenges created by widespread rooftop solar.

Despite the prevailing belief that rooftop solar benefits all consumers, energy market bodies and policymakers have failed to provide clear evidence it reduces total system costs. Instead, as this analysis will demonstrate, the vision of a solar-powered paradise may be more illusion than reality.

2. Energy market bodies’ blind faith in solar paradise

Australia’s energy market bodies have lauded rooftop solar and home batteries as key components in achieving emissions reduction goals. They argue that greater consumer participation in energy generation will not only reduce emissions but also lower total system costs and enhance grid stability. However, the claim that increased penetration of rooftop solar and home batteries will lower total system costs has not been rigorously tested or backed by comprehensive modelling. This is concerning, as pursuing a suboptimal emissions reduction strategy that increases system costs unnecessarily could lead to higher electricity bills, ultimately jeopardising public support for decarbonisation.

In December 2023, the energy ministers revised the National Electricity Objective (NEO) to incorporate emissions reduction, alongside price, reliability, and security of electricity supply, as a key consideration for energy regulators. However, while emissions reduction is now formally part of the NEO, it is intended to be considered alongside — not prioritised above — other objectives; including affordability and reliability.[7]

Despite this balanced mandate, AEMO, the Australian Energy Regulator (AER), and Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) frequently prioritise rooftop solar and battery adoption on the belief that it reduces both emissions and electricity costs. However, this is not supported by comprehensive evidence or rigorous cost-benefit modelling.

AEMO has, for example, estimated $4.1 billion in savings specifically from coordinating home batteries compared to uncoordinated storage.[8] However, it has not assessed whether encouraging widespread rooftop solar and home battery uptake itself delivers lower total system costs relative to, for instance, investing more heavily in utility-scale renewables.[9] Uptake and coordination are two separate issues: just because efficiency gains can be made by coordinating consumer energy resources (CER), it does not follow that widespread adoption of CER is cost-effective or beneficial for the overall energy system.

Nevertheless, AEMO’s ISP — the federal government’s energy transition blueprint — relies on a four-fold increase in rooftop solar and 34-fold increase in home batteries by 2050 to offset a significant amount of large-scale utility generation and storage needed by the grid.[10] Given the significant shift of generation responsibility onto households, one would reasonably expect AEMO to conduct a thorough cost-benefit analysis to demonstrate the net benefits to consumers of such an approach. Instead, the ISP treats CER uptake as an exogenous fixed assumption rather than an endogenous variable optimised alongside utility-scale investments. This approach forces utility-scale investments to be planned around an optimistic and uncosted CER forecast; inherently constraining the exploration of lower-cost scenarios where consumer energy investments play a smaller role.

Recent statements made by AEMO’s CEO Daniel Westerman to a Senate inquiry illustrate AEMO’s belief in Australia’s solar-driven future:

Let me first acknowledge the absolutely critical and important role that consumers play in Australia’s energy transition. Australia has one of the highest adoption rates of rooftop solar in the world. It is a very important part of our energy system both today and into the future. As consumers continue to invest in their own resources, both rooftop solar and batteries, electric vehicles and other smart appliances, that’s right; the Integrated System Plan did find in its analysis that if those resources are able to participate in the broader market, the whole system will cost $4.1 billion less for consumers. We say it’s important to find ways for consumers and their devices to participate in the broader system because that results in lower costs for everyone, not just for those who can afford those devices.[11]

Yet Westerman’s statement relies entirely on a narrowly-scoped analysis of battery coordination, without comparing CER uptake itself against large-scale investment alternatives.[12] Thus, Australia’s current energy blueprint, which expects consumers to shoulder substantial financial burdens, relies on unproven assumptions rather than robust evidence.

Critically, consumers who invest in rooftop solar and batteries expect financial returns (see Section 3), adding to the total cost of the energy system. By forcing significant rooftop solar and home battery installations into the current renewable energy masterplan — which crowds out utility-scale projects — energy market bodies cannot ensure the energy transition delivers the lowest-cost system for consumers. This approach not only falls short of the NEO’s mandate to balance affordability alongside emissions reduction but also jeopardises reliability if optimistic CER projections fail to materialise. Should rooftop solar and battery adoption lag behind AEMO’s forecasts, additional utility-scale infrastructure — including more fossil fuel generation — would need to be developed reactively rather than through forward planning; leading to a suboptimal outcome that raises both costs and emissions.

The AER has also similarly stated in a recent report that “consumer investments in CER can help to lower costs for all electricity consumers” and citing AEMO’s $4.1 billion of battery coordination savings figure to back up their claim.[13] The AER’s CER strategy, launched in 2023, explicitly aims to “support consumers to own energy resources and use those resources to consume, store and trade energy as they choose”.[14] The AER has cited AEMO to support its strategic goals, using an even larger, albeit unreferenced figure: “AEMO’s ISP notes that successful integration of CER will offset up to $11 billion in network augmentation costs”.[15] Yet, the AER has not demonstrated that increasing CER investments will be the most cost-effective way to transition the grid.

The AEMC has echoed these sentiments, reiterating that “CER offers substantial benefits for consumers”.[16] In a recent speech, AEMC Chair Anna Collyer emphasised “you know how important it is to us that the role of consumer energy resources, or CER, is recognised and supported”.[17] Like the AER, the AEMC cites AEMO’s flawed modelling, focused solely on the coordination of CER, to imply greater uptake will lower consumer bills. As the AEMC stated in its submission to the Senate inquiry:

Effective integration and coordination of CER could deliver net benefits estimated at between $1 billion and $6.3 billion from 2030-2040. These benefits ultimately flow back as lower energy bills to all consumers, including those who do not have direct access to the technology. The stronger CER is in our system, the more confident we can be about overall power supply and the less back-up infrastructure we need to build at utility-scale. AEMO’s 2024 Integrated System Plan suggests that coordinated CER can avoid $4.1 billion in additional grid-scale investment, directly impacting consumer bills.[18]

Notably absent from the AEMC’s statements are any consideration of whether rooftop solar and home batteries might increase total system costs — and, by extension, household electricity bills. Instead, the AEMC has placed CER reform among its top five priorities, with a stated focus on “consumers’ freedom to choose how their energy resources are used and how market arrangements should enable CER to improve the efficiency of the system to benefit all”.[19] The assumption that rooftop solar and home batteries can benefit all consumers remains unchallenged by the energy regulator or the market commission.

The energy market bodies’ belief in the rooftop solar paradise is deeply concerning. The AER and AEMC’s fundamental responsibility is to safeguard the long-term interests of consumers, yet they have shown little interest in determining the costs and benefits of the mass uptake of CER they actively promote. Instead of independent scrutiny, all energy bodies refer to AEMO’s flawed modelling; which assumes — rather than proves — that widespread CER adoption will lower system costs. As this paper will show, the benefits of rooftop solar have been greatly oversold, while its true cost to consumers — hidden within their energy bills — has begun to surface.

3. Rooftop solar uptake depends on high financial returns

While early adopters of rooftop solar may have been motivated by environmental concerns or curiosity about emerging technology, it is the promise of substantial financial savings that has driven the majority of households to embrace solar power.

Empirical studies consistently show that economic incentives are the strongest motivators for rooftop solar uptake. A CSIRO study, for example, found 75% of rooftop solar owners cited financial reasons for their decision, compared to only 53% motivated by environmental factors.[20] Similarly, a Newgate Research report for Energy Consumers Australia revealed the top motivations for installing solar were reducing or eliminating electricity bills and saving money through self-consumption of solar power.[21] Another survey by Ausgrid corroborated these findings, with 91% of respondents stating that saving on energy bills was very or extremely important in their decision to install solar panels.[22]

In short, most households are unlikely to install rooftop solar unless they perceive it as a significant financial benefit. Federal and state governments have offered various subsidies to incentivise rooftop solar uptake, particularly during periods when the technology was expensive and less accessible. These incentives, including upfront rebates and generous feed-in tariff schemes, have provided compelling financial benefits to rooftop solar owners, on top of the savings from using their solar energy directly to power their homes.

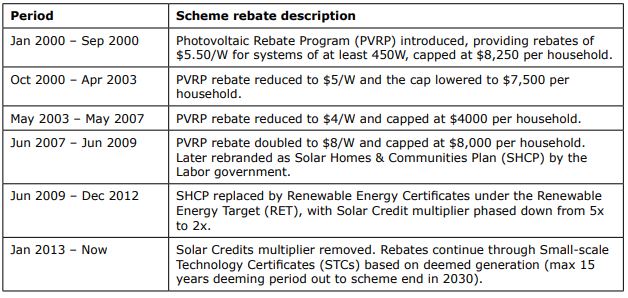

3.1 Federal government rebates made rooftop solar more affordable

Australia’s federal subsidies and rebates for rooftop solar have undergone various changes since the introduction of the Photovoltaic Rebate Program (PVRP) in 2000 (Table 1). Initially, the PVRP provided rebates of $5.50 per watt for systems of at least 450 W, capped at $8,250 per household. Over time, challenges like oversubscription and budget constraints led to adjustments in rebate rates and household caps. By 2003, the rebate was reduced to $4/W, with a maximum of $4,000 per household. However, in 2007, as the federal election approached, the Coalition government, facing political pressure to close the policy gap with the Labor opposition on climate change, increased the rebate to $8/W, with a cap of $8,000 per household. After coming into power, the Labor government rebranded the program as the Solar Homes and Communities Plan (SHCP). The revised PVRP-SHCP program significantly altered the financial calculus for rooftop solar, [23] covering up to 45% of installation cost for a 1.5kW solar system.

Table 1. Federal rooftop solar rebates over time

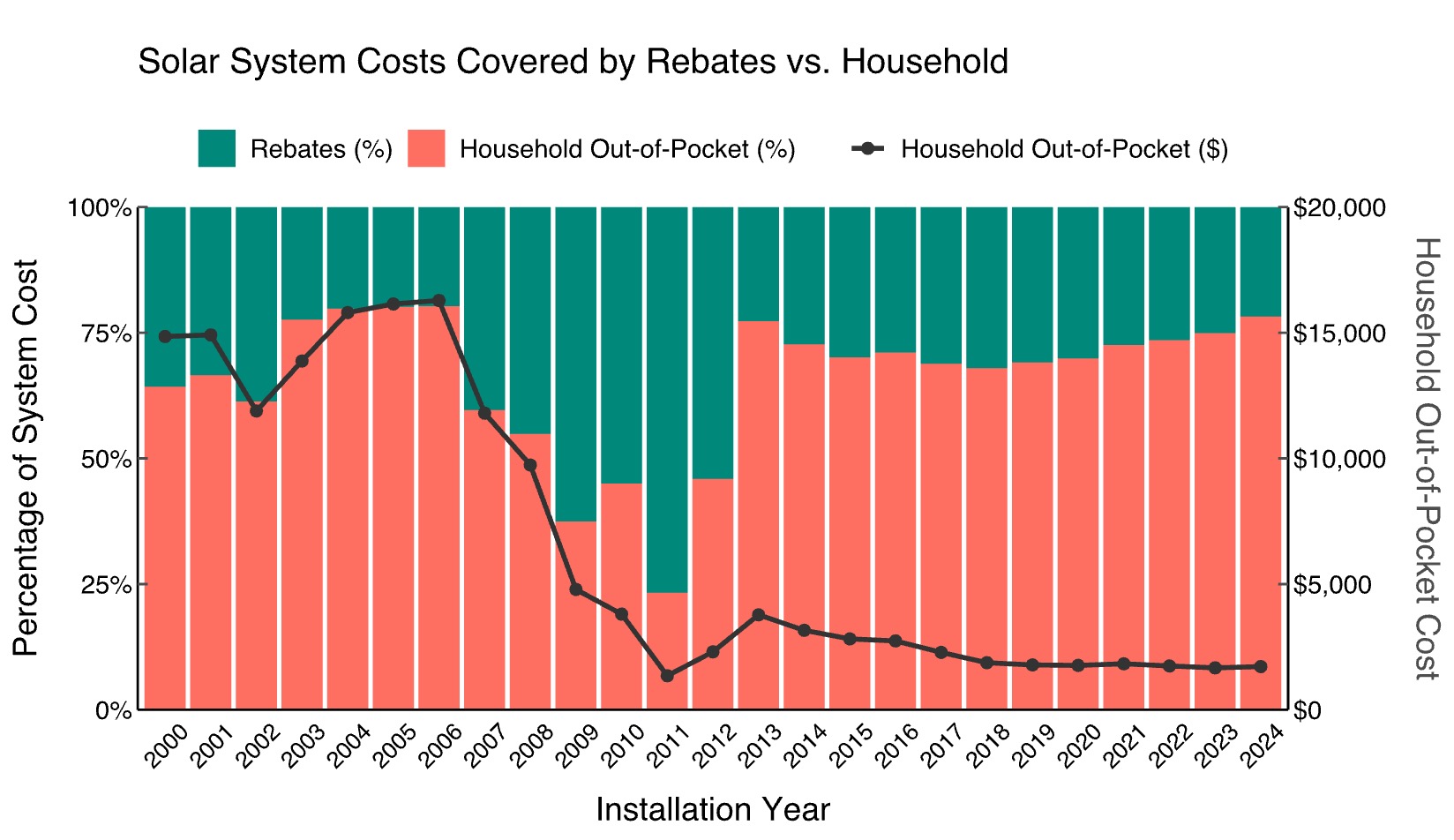

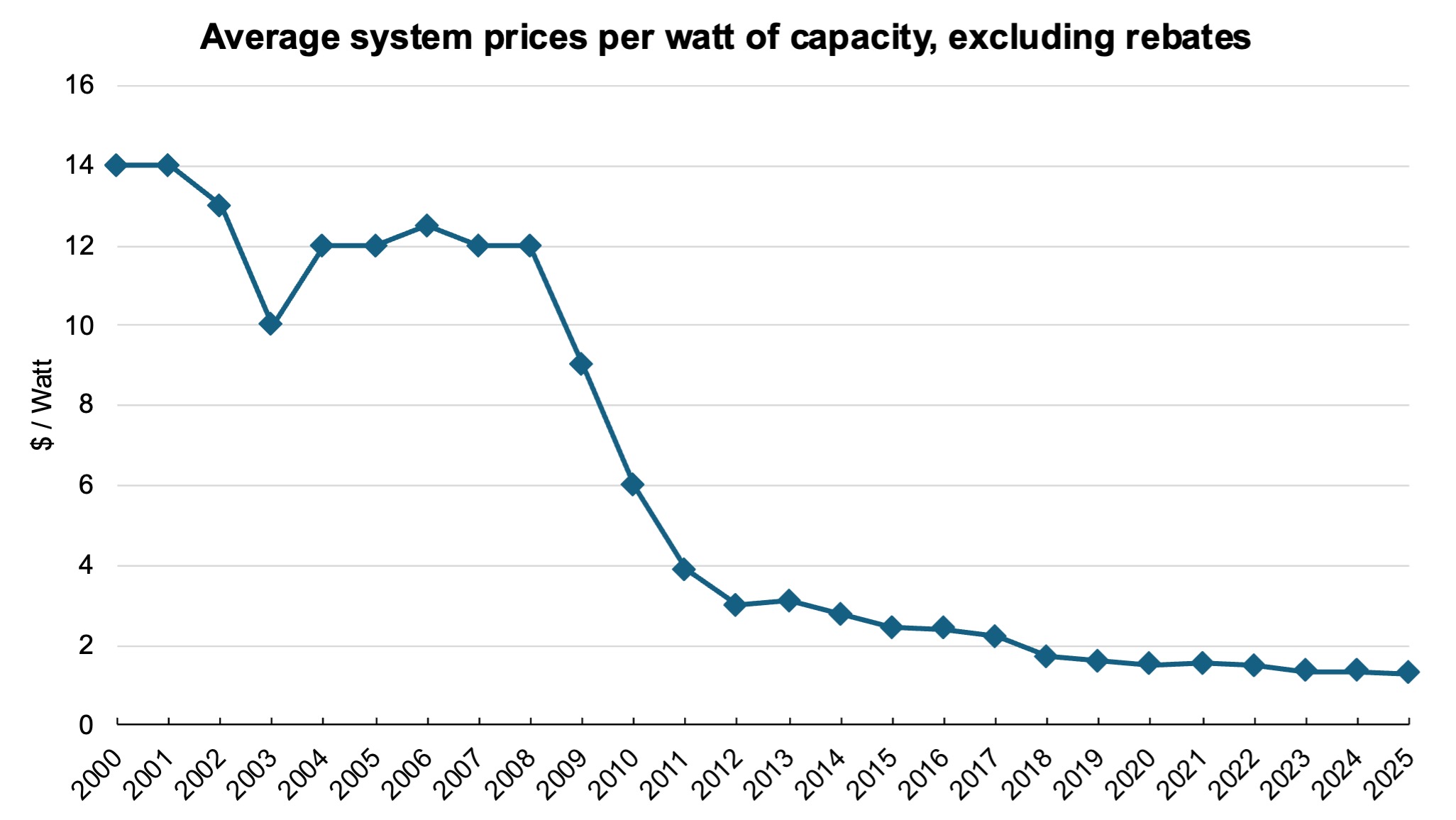

From 2009 to 2012, government rebates as a percentage of costs for a 1.5 kW system reached their highest (Figure 2). On 9 June 2009, the PVRP-SHCP scheme was abruptly replaced by the Solar Credits Program under the Renewable Energy Target (RET) reforms. The program introduced a multiplier for Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs), which are tradable certificates representing one megawatt-hour (MWh) of electricity generated from renewable sources. In 2011, RECs were split into large-scale and small-scale certificates, with rooftop solar systems eligible for small-scale technology certificates (STCs). Electricity retailers and other liable entities were mandated to purchase and surrender a specific number of certificates annually to comply with their renewable energy obligations under the RET, creating an indirect subsidy for renewable energy providers.

Initially, the Solar Credits Program applied a 5x multiplier to the number of certificates created for the first 1.5 kW of a system’s capacity; providing substantial upfront savings for solar installations. The multiplier was gradually reduced to 3x in mid-2011, 2x in mid-2012, and finally phased out by January 2013.[24] After this, rebates continued through STCs, with certificates calculated based on the system’s deemed electricity generation — the amount the system is expected to generate — over a maximum period of 15 years. This deeming period decreases annually as the RET approaches its end in 2030.

Figure 2. Proportion of 1.5 kW solar system costs covered by government rebates vs. household (2000–2024)

3.2 State governments implemented generous feed-in tariffs to accelerate adoption

In addition to federal rebates, state and territory governments introduced feed-in tariff schemes to further incentivise rooftop solar adoption. These schemes provided payments for electricity generated by solar systems, either as government subsidies or by mandating retailers to pay specific rates.

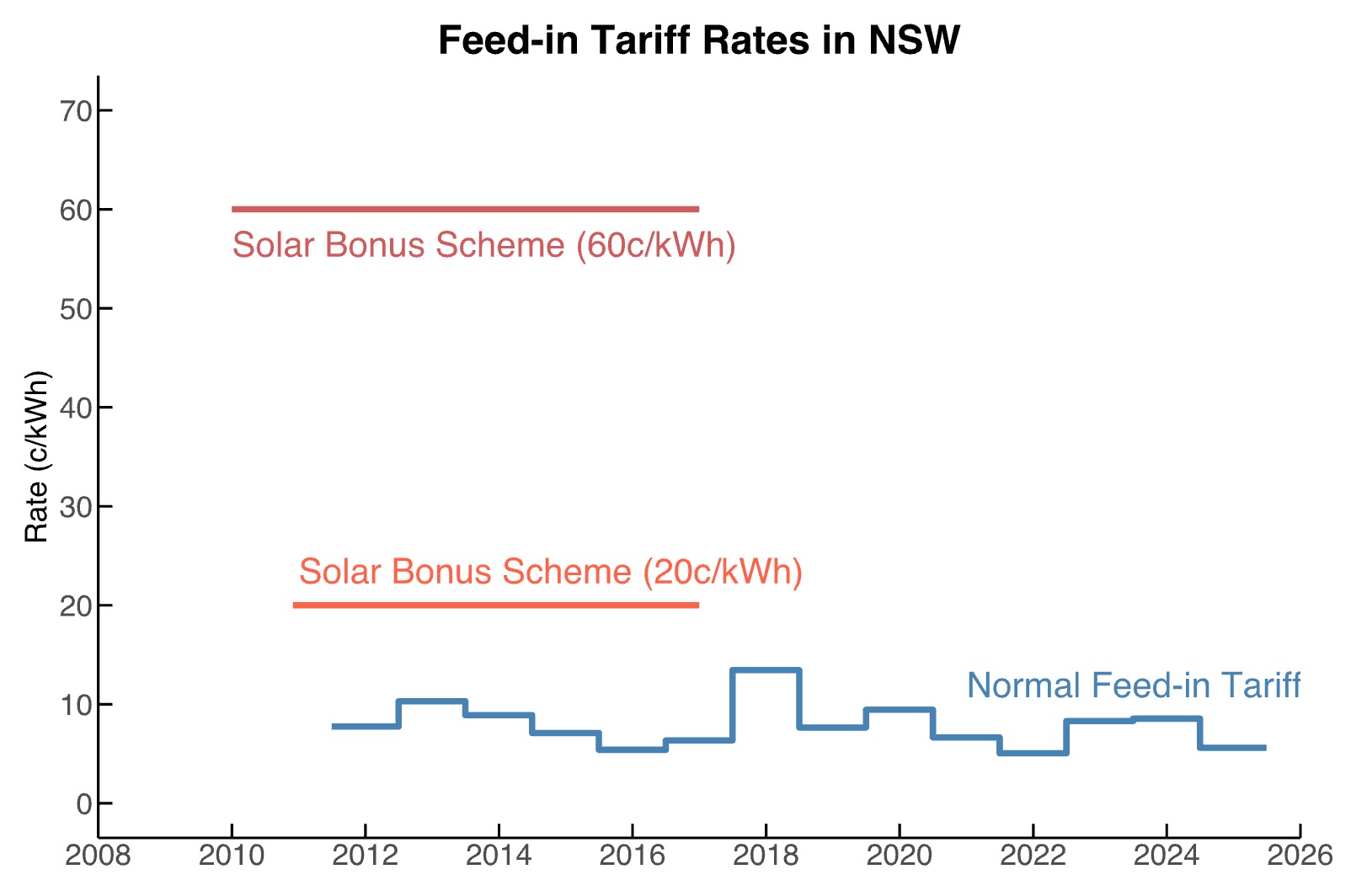

For instance, the NSW government’s Solar Bonus Scheme, launched in January 2010, offered a gross feed-in tariff of 60 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh), compensating solar households for all electricity generated including self-consumption. This generous scheme quickly became oversubscribed, leading the government to reduce the rate for new participants to 20 cents/kWh in December 2010 and closed the program to new applicants in April 2011. Households that applied to join the Scheme by 28 April 2011 were allowed to complete their connection by 30 June 2012 to receive Scheme payments.[25] Eligible participants continued to receive the gross feed-in tariff until the last Scheme payment was made on 31 December 2016. Other states implemented similar programs, albeit with varying rates and structures, contributing to significant solar uptake nationwide.

As shown in Figure 3, the Solar Bonus Scheme’s 60c/kWh and 20c/kWh tariffs were around two to six times higher than the average retailer feed-in tariffs.[26] The premium tariffs were available to applicants that installed solar systems before the end of November 2010 (for the 60c/kWh rate) or June 2011 (for the 20c/kWh rate) and remained in effect until the Scheme concluded on 31 December 2016. The Scheme greatly improved the return on investment for households during this period.

Figure 3. Feed-in tariff rates in New South Wales (2010–2025)

3.3 Measuring the return on investment for rooftop solar in New South Wales

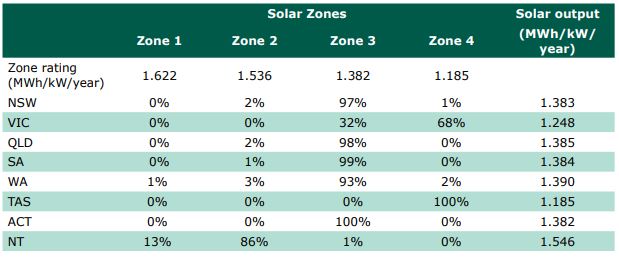

To illustrate the relationship between financial returns and the uptake of rooftop solar, an analysis was conducted to estimate the lifetime bill savings and payback period for the average solar household in NSW. The analysis considers how evolving factors—such as system costs, government incentives, feed-in tariffs, and average system size—have influenced the financial payback of rooftop solar over time.

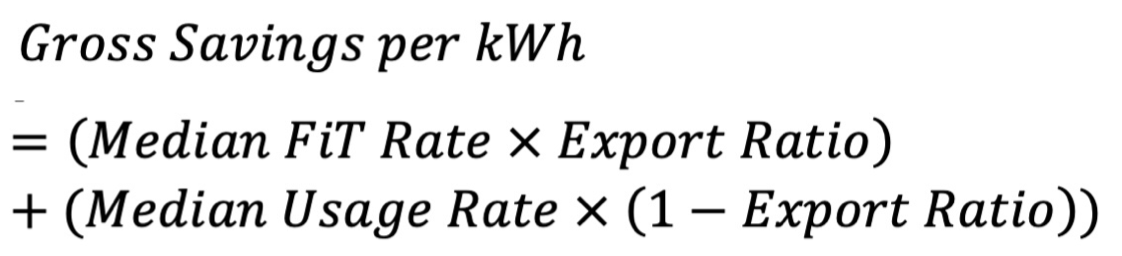

Households have two ways of saving on electricity costs through rooftop solar:

- Export savings are earned through feed-in tariffs for a household’s surplus solar energy. The NSW government’s Solar Bonus Scheme initially offered premium feed-in tariffs to encourage adoption. After the scheme ended, retailers continued to provide feed-in tariffs, with rates monitored and benchmarked by the Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal (IPART).

- Self-consumption savings represent the avoided cost of purchasing electricity from the grid by a household using its own solar energy. With retail electricity rates often 3-4 times higher than feed-in tariff rates post-Scheme, self-consumption has become the primary financial driver for solar households. As electricity prices continue to rise, self-consumption savings have grown, making rooftop solar increasingly attractive.

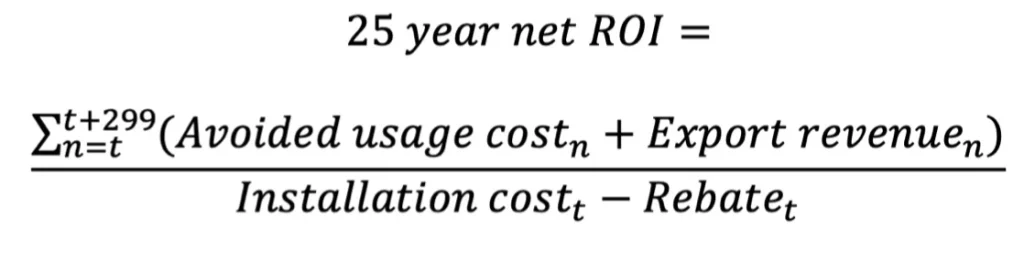

In this analysis, the financial returns for rooftop solar installations are calculated for systems installed each month from January 2000 to November 2024. The upfront installation cost (adjusted for government rebates available at the time) is calculated alongside monthly bill savings. Three key metrics are used to track the financial returns of rooftop solar:

- Payback period measures the time it takes for cumulative bill savings to equal or exceed the net installation cost. It is a practical indicator of how quickly households can recover their initial investment and is a widely used metric, often featured in popular online calculators. For installations that do not break even within the analysis period (to November 2024), the remaining time to reach the break-even point is estimated by dividing the residual cost by the latest monthly savings. This approach aligns with industry findings that households generally base investment decisions on current electricity prices with only short-term adjustments, rather than relying on long-term price forecasts.[27]

- 25-year net return on investment (ROI) shows how much money households save (or lose) over 25 years compared to the upfront installation cost. The ROI is calculated by subtracting the installation cost (net of government rebates) from the total bill savings, then dividing the net savings by the installation cost. For installations where the 25-year period extends beyond the analysis timeframe (to November 2024), the ROI is estimated by projecting the latest month’s bill savings forward until the full 25 years is reached.

- 25-year internal rate of return (IRR) represents the annualised rate of return that equates the present value of a rooftop solar system’s expected lifetime bill savings to the upfront installation cost. A higher IRR indicates a more attractive financial return, while a negative IRR suggests that the investment does not recover its initial cost within the assumed timeframe.

For a detailed discussion of the inputs, assumptions, and methodology used in this analysis, please refer to Section 11.1 in the Appendix.

3.4 Financial returns drive rooftop solar adoption in New South Wales

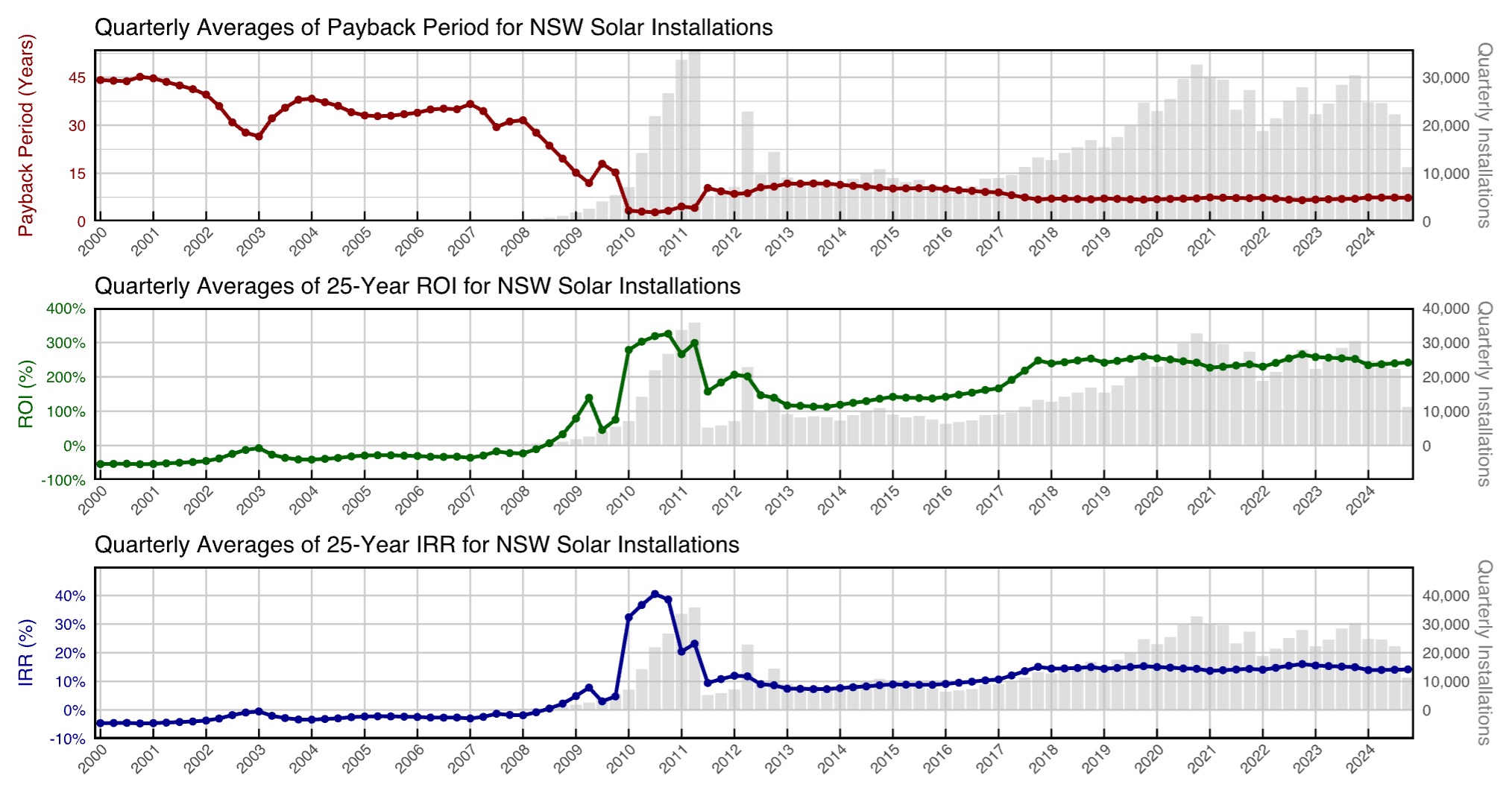

The results reveal a strong correlation between financial returns and the uptake of rooftop solar in NSW (see Figure 4). Before 2008, installing rooftop solar was not a good financial investment for most households. While the government provided significant rebates, the upfront cost of solar systems was too high, and the savings on electricity bills were too small to recover the cost over the system’s lifetime. As a result, the number of installations in NSW was miniscule, with approximately 20 systems installed per month. This finding aligns with previous studies that suggest early adopters were primarily motivated by environmental concerns and technological interest, rather than financial benefits.[28]

From 2008 onwards, financial returns from rooftop solar installations improved markedly. The cost of solar technology dropped, and government incentives became much more generous. In 2010, the NSW government introduced the Solar Bonus Scheme, offering generous gross feed-in tariffs. Households that secured these tariffs during this Scheme could achieve a payback period as short as two to three years for typical systems sized between 1.5 and 2.5 kilowatts during the early 2010s. For these installations, the average estimated net return was 298 percent over 25 years, effectively tripling the upfront investment over the system’s lifetime. Unsurprisingly, this period saw a surge in installations, with approximately 140,000 systems installed, equating to an average of 7,700 installations per month. This trend aligns with previous studies showing that later adopters of rooftop solar are primarily motivated by financial benefits.[29]

In April 2011, the Solar Bonus Scheme was closed to new customers. Without the high feed-in tariffs, financial returns for new rooftop solar installations moderated, and the payback period increased from four to ten years. As a result, new installations slowed down, falling to about 3,350 per month between July 2011 and December 2015. While solar still saved households money, the lower returns made it less economically attractive; especially since the rapid decline in technology costs also began to slow down.

However, from 2016 onwards, rising retail electricity prices and feed-in tariffs led to renewed growth in rooftop solar adoption. Retail electricity prices surged by 40%, increasing from 23c/kWh in 2016 to 32c/kWh in 2024.[30] Meanwhile, feed-in tariffs peaked at 13.5c/kWh in 2018 before gradually declining to 8.6c/kWh in 2024.[31] The payback period fell to approximately seven years, even as households installed much larger systems — nearly doubling in size from 5.3 kW in 2016 to 10.2 kW in 2024. This meant that even with higher upfront costs, the savings on electricity bills were large enough to offset the investment more quickly. The improvement in financial returns drove installation rates back to levels comparable to those seen during the Solar Bonus Scheme.

While government subsidies are now much smaller than they were in 2010, solar customers continue to benefit from indirect subsidies embedded in the structure of electricity network tariffs. Households with solar can reduce their grid usage and benefit from feed-in tariffs, but because network costs are primarily recovered through volumetric charges, the burden of paying for the grid shifts disproportionately onto non-solar customers. This has created an inequitable system where those without solar end up subsidising those who have it — something that will be explored in more detail in Section 4.6.

After the Solar Bonus Scheme ended, the estimated 25-year nominal IRR for rooftop solar in NSW rose from 9% in July 2011 to a peak of 16% by late 2022, then settling at around 14% by the end of 2024, with an average of 12.2% over the period. Adjusting for an average annual inflation rate of 2.55%, the real IRR for rooftop solar over this period is approximately 9.4%.[32] This return is substantially higher than the real pre-tax weighted average cost of capital (WACC) benchmarks adopted for utility-scale solar (7%) and onshore wind (7.5%) in the ISP.[33] In other words, households investing in rooftop solar are likely to expect much higher returns than the return assumed for large-scale renewable projects in the energy transition masterplan.

Figure 4. Payback period (years), 25-year ROI (%), and 25-year IRR (%) for rooftop solar installations in New South Wales from January 2000 to November 2024. The x-axis represents the installation dates, and monthly calculations are presented as quarterly averages

4. How much does rooftop solar save the grid?

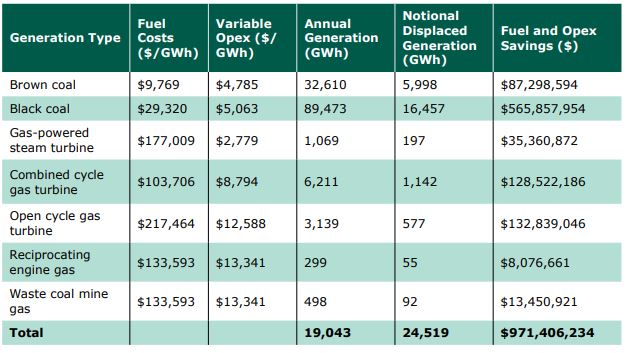

The cost savings for our electricity system arising from rooftop solar generation at best comprise the marginal savings from reduced coal and gas plant generation. Our calculations indicate rooftop solar in the NEM saves the system at most 4c/kWh through averted fuel costs and variable operating expenditure at coal and gas plants.

Rooftop solar generation does not save costs for the grid through averted capital expenditure on generators. There is currently more than enough dispatchable capacity (i.e. coal, gas and hydro) to meet peak demand in the NEM.[34] As explained in Section 5.1, rooftop solar will not save on dispatchable generator’s capital costs in future, as it does not reliably reduce forecast critical peak demand, meaning 100% backup generation capacity will always be necessary for the amount of rooftop solar in the system.

Rooftop solar also does not help the grid save on distribution network costs but, in fact, increases network costs at high penetration levels due to the operational issues caused by its inherent instability, as explained in Section 5.1.

We therefore calculated grid cost savings from rooftop solar by estimating the marginal savings from reduced production from coal and gas plants, namely the displaced fuel costs and variable operating expenditure (see Appendix 11.2 for methodology). Our estimate of grid cost savings is conservative, as we do not take into account increased distribution costs arising from high levels of rooftop solar penetration.

As shown in Table 2, fuel costs and variable opex ($/GWh) for each generation type were multiplied by the notional generation (GWh) for that type. The resulting estimated fuel and opex savings for each coal and gas generation type were added up, giving an annual total of $971 million, or 4c/kWh.

Table 2. Notional gas and coal generation displaced by rooftop solar (GWh) and associated fuel and opex savings ($) in the NEM

5. Rooftop solar and the distribution network

5.1 Rooftop solar does not save distribution costs through demand reduction

Renewables advocates commonly claim that rooftop solar not only reduces average demand on electricity from the grid due to self-consumption, but that it also lowers peak demand — typically referring to afternoon peaks.[35] However, for DNSPs, infrastructure planning and spending are driven by forecast critical peak demand — the highest of the peaks — rather than average or daily peak.[36] Just as bridges must be designed to withstand the heaviest load predicted to drive on them, not just the average load, network capacity must be built to accommodate extreme grid demand scenarios, not just typical conditions, within a given reliability standard.[37]

Rooftop solar cannot reliably reduce critical peak demand in each subsection of the grid, which means it cannot save on network upgrade costs without compromising reliability. As stated in AEMO’s 2024 Electricity Statement of Opportunities, rooftop solar systems “do not tend to contribute to lowering the scale of peak demands during extreme hot conditions in the summer or extreme cold conditions in the winter.”[38] Even if rooftop solar does reduce critical peak demand in one year, its lack of reliability means it may not do so in the next year. DNSPs must ensure their system capacity contains a margin above recent observed peak demands to allow for infrequent extreme weather conditions.[39] Equipment must be upgraded in accordance with forecast growth in demand regardless of any potential reductions from rooftop solar if reliability standards are to be met.

An example that illustrates why rooftop solar cannot save on network upgrade costs is the forecasting published by Energex, a Queensland DNSP. High uptake of rooftop solar in many states has greatly increased the difficulty of forecasting critical peak demand, as both demand and generation become reliant on the weather. As Energex states:

Historically, temperature was the major variable on peak demand (after systematic factors such as time of day and day of year). However, the scale of solar PV generation means that cloud cover can create variations in generation output (thereby changing the source of supply to Powerlink) greater than what would be seen from temperature changes.[40]

DNSPs do factor in the effects of rooftop solar output on forecast load profiles, including potential reductions in forecast critical peak demand, as rooftop solar has provided small reductions in previous years. In 2023, Energex estimated the 5,221 MW peak demand would have been 292 MW higher without rooftop solar, representing a reduction of 5.3%.[41] By comparison, the other Queensland DNSP, Ergon Energy, estimated a reduction of 23 MW from residential and commercial solar generation resulting in a peak of 2,637 MW — a 0.9% reduction.[42] But while these apparent demand reductions are network-wide estimates, network infrastructure experiences stress at the local level, so DNSPs must plan for forecast load growth in each subsection of the grid.[43] Ultimately, forecast local grid stress is what determines upgrade costs for a specific area. Statements that rooftop solar has provided system-wide reductions in critical peak demand in the past therefore do not support the claim that rooftop solar can be relied upon to reduce network costs in the future.

Additionally, critical peak demand reduction estimates are typically calculated on the half hour or hourly timescale. Energex uses hourly solar irradiance profiles and half-hourly maximum supply to forecast critical peak demand.[44] But these timescales cannot capture the drop in solar output that may occur from passing clouds. Ultimately, DNSPs must have enough capacity built into the grid to handle a sudden increase in load from rooftop solar households when passing clouds cause a sudden drop in generation. This happens on the timescale of seconds, as DNSPs must operate a network with a current alternating at a frequency of 50Hz, or 50 times per second.[45]

Energex has flagged recently-observed impacts on solar output from cloud cover on high-demand days:

Notably over the past few summer seasons, there has been significant weather events such as storms, or at the very least, rapid cloud cover, occurring on days with high demand. Due to the scale of rooftop solar PV uptake, if cloud cover occurs, this can create variations in solar generation output whilst internal consumption remains high, resulting in a sudden increased demand from the grid.[46]

These cloud-induced variations in output can be extreme. Data from AEMO indicate a solar farm’s output can be reduced by 80% in a 5-minute period due to passing clouds.[47] Rooftop solar systems in cities face the same problem.[48] It is therefore unsurprising that when engaging in network planning, Energex models forecast load with and without the support of rooftop solar:

These models are replicated for two network load scenarios that have been considered, native load and loading with DER [distributed energy resources, including rooftop solar]. The native load scenario provides indication of areas of the network may require augmentation due to load, impacts of phenomenon like solar masking being considered. The DER scenario highlight areas of the network that have high penetration of generation and capacity constraints or areas where capacity for Embedded Generation remains.[49]

Since customers tend to consume more electricity during peak times after installing rooftop solar,[50] solar customers contribute to load growth that may be ‘masked’ by high solar output providing critical peak demand reduction in some years. If the system has not been sufficiently augmented to handle underlying load growth due to this ‘solar masking’, there will be a significant risk of grid stress in years in which the peak occurs during a time of low solar output. Thus, the most important factor for determining which areas require augmentation arising from critical peak demand growth (and the resultant upgrade costs) is what Energex calls native load; underlying demand before solar output is factored in. If a DNSP were to rely on rooftop solar providing a given reduction in critical peak demand, it would risk such a reduction failing to eventuate due to cloud cover, and the system being unable to cope with the resultant peak. Any cost saving arising from averted network upgrades due to rooftop solar reducing critical peak demand is therefore a false economy because it simply increases the risk of reliability standards being breached, as it depends on an unreliable source of demand reduction.

5.2 Rooftop solar increases distribution costs by introducing instability

Rooftop solar is likely to increase distribution costs in an unpredictable manner. There are a wide range of estimates for network upgrade costs necessitated by rooftop solar due to the destabilising effect it has on the grid as it reaches higher penetration levels.

Unlike the traditional one-way flow from large-scale generators to consumers which the electricity grid was designed for, rooftop solar requires two-way flow between exporting consumers and the grid.[51] High penetrations of rooftop solar place stress on the grid by reducing critical minimum demand[52] and causing synchronous grid generators (i.e., coal, gas and hydro) to withdraw supply. Without the voltage management, frequency control and inertia of synchronous generators, the grid may be unable to operate safely.[53] As a result of increasing penetration of rooftop solar, operational issues may become more frequent, including an increase in power loss from distribution, voltage fluctuations and frequent operation of circuit breakers and fuses.[54]

The degraded quality of electricity supply resulting from these operational issues ultimately increases costs for consumers through shortening the lifespans of household appliances. For example, a study based on the South Australian grid found overvoltage of 10% increases the power consumption of lights by 16% and reduces their life span by 17% for fluorescent lights and 60% for incandescent lights. The study found overvoltage went from zero hours at 2018 rooftop solar penetration levels (i.e., 9%[55]) to almost 2000 hours with an additional 30% rooftop solar penetration.[56] Voltage increases of more than 20% can seriously damage appliances – as occurred in Byron Bay on June 29, when 34 houses experienced a power surge that destroyed tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of appliances in each house.[57]

These operational issues also shorten the lifespan of distribution equipment and require greater capital expenditure by DNSPs, increasing costs passed onto consumers. Queensland’s Ergon Energy and Energex have indicated that daily minimum demand caused by the increase of rooftop solar uptake causes a range of issues that affect capex, including reverse power flow potentially reducing the life of zone substation transformers.[58] SA Power Networks is implementing voltage management services and installing prescriptive Under Frequency Load Shedding infrastructure to manage rooftop-solar-induced overvoltage and reverse power flows.[59] Currently, SA Power Networks uses a brute force method of curtailing solar when the grid is congested by deliberately inducing overvoltage to trip solar panel inverters, disconnecting them from the grid.[60] To avoid such an extreme measure in Victoria, AEMO recently introduced the Victorian Emergency Backstop Mechanism, which will allow DNSPs to remotely switch off rooftop solar systems during periods of minimum demand.[61] AEMO wants to extend this mechanism to all states in the NEM.[62]

Costs for integrating rooftop solar are near zero until hosting capacity is reached, at which point costs increase incrementally, before reaching an uncertain level at which large outlays are required for system-wide upgrades.[63] This uncertainty of the different cost thresholds leads to a wide range of estimates for total distribution network upgrade costs required to make the grid resilient in the face of high penetrations of rooftop solar. A study of the Victorian grid quantified the grid upgrade costs associated with accommodating 60% of customers having rooftop solar without resorting to broad-scale adoption of batteries and/or curtailment of solar generation.[64] Annual costs per customer ranged from $47 to $886 in rural areas and $82 to $2,525 in urban areas.[65] If costs in the upper bound of these ranges were to eventuate as rooftop solar penetration levels increase, this would place great financial strain on many customers, making it unlikely to be accepted by the public without further government subsidies.

Given the wide range of cost estimates and uncertainty surrounding cost inflection points, we have not attempted to include distribution network upgrade costs necessitated by rooftop solar in our calculation of grid cost savings per kWh of rooftop solar generation. In other words, we have assumed the costs to the system from necessary distribution network upgrades to be zero. This provides a conservative estimate of grid cost savings, meaning our analysis likely overstates the benefits of rooftop solar, particularly if network upgrade costs end up being in the upper range of estimates.

In light of a recent AER report stating DNSPs currently use only about 1% of their total expenditure to provide export services, renewables advocates have argued this indicates there are no cross-subsidies from non-solar to solar households.[66] But in fact, cross-subsidies exist, as outlined in Section 6, even before taking into account current network expenditure or any future increases in network expenditure necessitated by increased rooftop solar penetration.

6. Rooftop solar owners are earning outsized bill savings

The savings rooftop solar customers receive on their energy bills arise from self-consumption (averted usage costs) and feed-in tariffs (payments for exported excess energy), less any applicable solar meter fees. However, these bill savings are around 2 to 4.5 times larger than the 4c/kWh that rooftop solar can plausibly save the system.

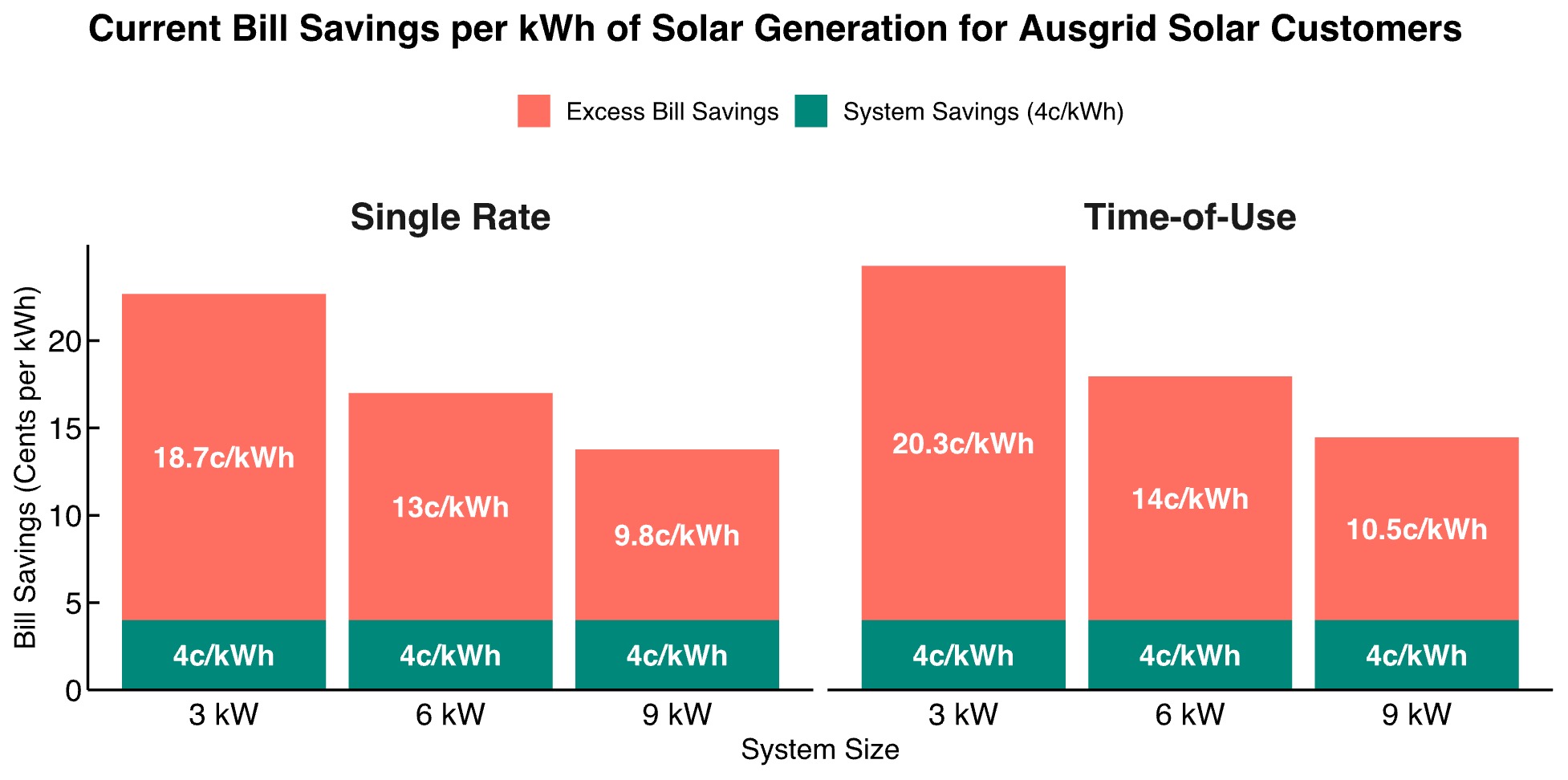

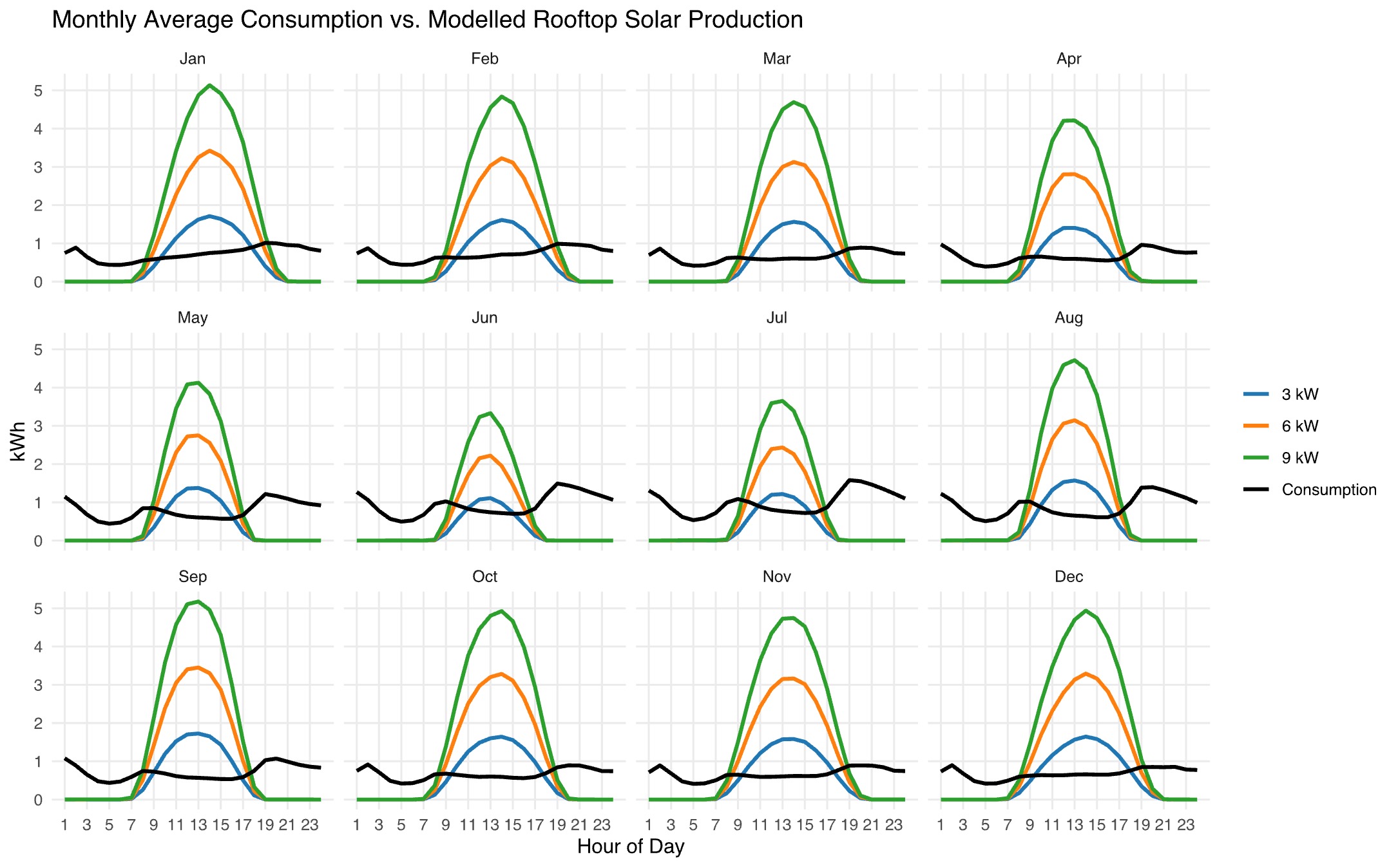

Figure 5 presents CIS analysis of the median bill savings in c/kWh of solar generation for typical rooftop solar customers in the NEM with 3 kW, 6 kW, and 9 kW systems and no home batteries (see Appendix 11.3 for methodology). Customers on single-rate tariffs averted between 9 and 18c/kWh, while those on time-of-use tariffs averted between 8 and 16c/kWh. This represents substantial outsized savings from self-consumption and exports far higher than warranted, given rooftop solar generation provides at most 4c/kWh of value to the grid.

Figure 5. Bill savings for rooftop solar customers on both single rate and time-of-use tariffs exceed electricity system savings from rooftop solar generation (4c/kWh) in all NEM states and for all modelled rooftop solar system sizes

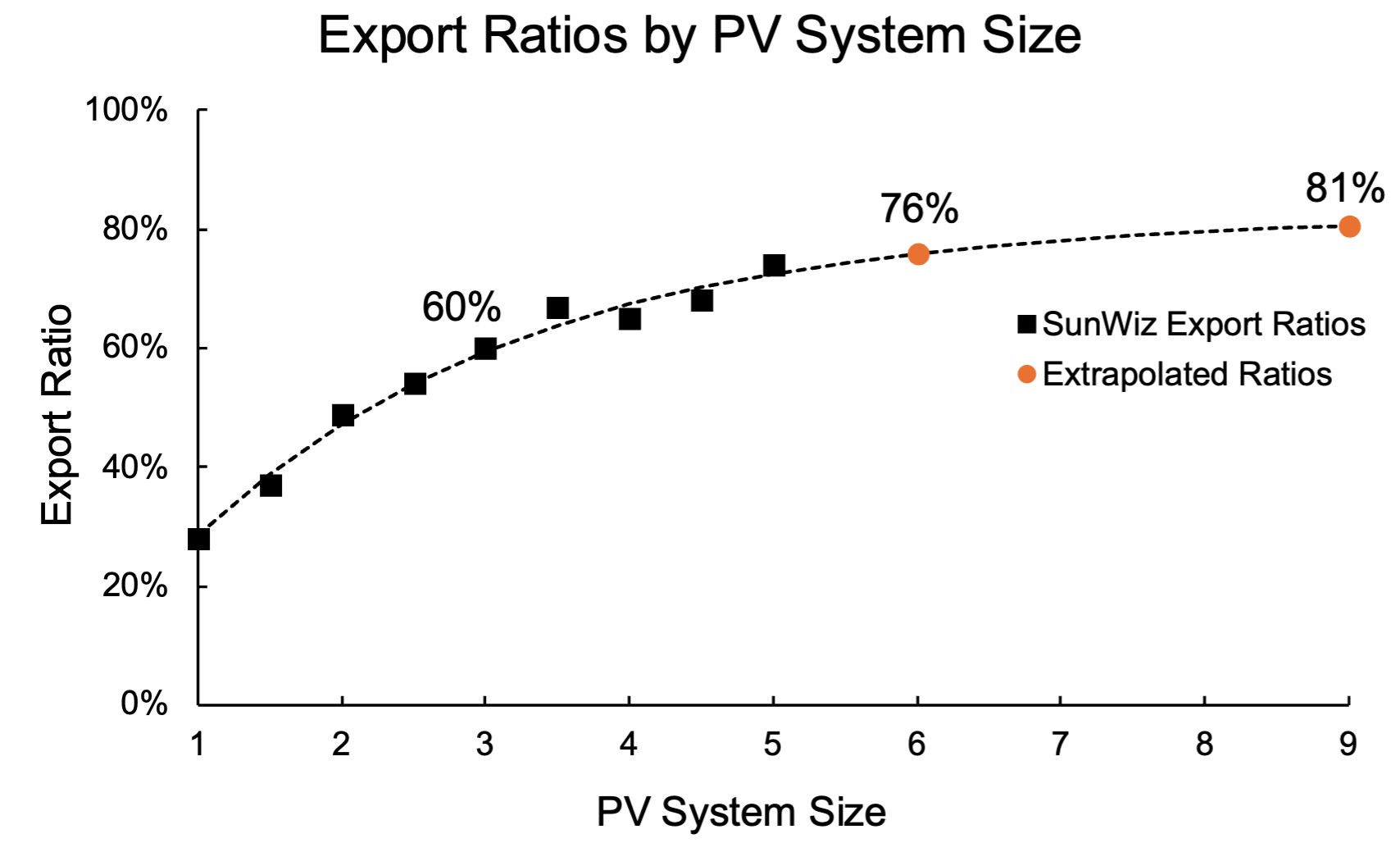

While larger systems provide smaller bill savings on a per kWh basis, this will typically translate to larger total savings on energy bills in dollar terms due to greater generation volumes for larger systems compared to smaller systems (see Section 7 for further explanation).

Single-rate retail tariffs charge the same rate for electricity usage at all times, while time-of-use retail tariffs charge different rates at different times, typically divided into ‘peak’, ‘off-peak’ and/or ‘shoulder’ rates. Given the lack of hourly self-consumption data in many states, we chose to default to the shoulder rate for time-of-use customers’ averted usage tariffs. This is because shoulder rates are typically charged during peak solar hours in the morning and early afternoon, so most self-consumption should generally occur at these rates. However, some retailers — particularly in Tasmania and Victoria — have only peak and off-peak periods, in which case the off-peak tariff was assumed to be averted. These assumptions represent an underestimate of time-of-use solar customers’ bill savings, as a portion of self-consumption will occur during peak periods — generally falling between 2pm and 9pm — during which, much higher rates are charged. Thus, most time-of-use solar customers will likely have higher bill savings per kWh than shown.

6.1 Rooftop solar owners are being cross-subsidised by non-solar customers

The gap between what solar customers are saving and the benefit they are providing to the grid demonstrates that non-solar customers are cross-subsidising solar customers. In other words, solar customers are being compensated substantially more than is warranted by the actual cost reductions their solar generation provides to the grid. Cross-subsidies arise because retailers must recoup all their costs from customers — including network charges from DNSPs — so if one group (rooftop solar owners) is given outsized savings, another group (non-rooftop-solar owners) must be charged more to cover the difference. This is reinforced by previous research indicating the average rooftop solar household avoids a disproportionately large component of network charges, which drives marginal investments in solar capacity above their otherwise efficient level.[67]

One argument for maintaining cross-subsidies is that this provides solar owners with payments representing the value of emissions reduction arising from their solar output. But as explained in Section 2, the lack of rigorous modelling supporting broadscale uptake of rooftop solar as the most cost-effective path to emissions reduction is problematic. By forcing non-solar customers to cross-subsidise solar customers, the energy bodies have created a system that is unable to provide the least-cost pathway for reducing emissions. If solar customers are to be paid according to the value of emissions reduction, this must be done in a transparent and technology-neutral manner, with rigorous modelling to determine the relative costs and benefits of different options. Cross-subsidies in network tariffs are a poor method for incentivising cost-effective emissions reduction.

Previous research has shown removing cross-subsidies from non-solar customers would have a material effect on retail bills — even under the assumption that rooftop solar provides distribution cost savings by lowering maximum demand, which is not the case.[68] If cross-subsidies were eliminated, rooftop solar installations would likely plummet, given the majority of consumers who invest in rooftop solar do so because of the financial benefits, as illustrated in Section 3.

AEMO’s ISP relies on a four-fold increase in rooftop solar in the National Electricity Market by 2050.[69] One analysis suggests an average cost of $18,000 for each customer to achieve such a large increase.[70] The question remains as to how this will be achieved without cross-subsidies causing intolerably high bill increases for the remaining consumers who do not have rooftop solar. To reach this goal, governments would need to introduce even greater subsidies for electricity bills, further burdening the taxpayer and stoking inflation.

6.2 Current tariff structures enable cross-subsidies at the expense of consumers without rooftop solar

The cross-subsidies from non-solar to solar customers have been enabled by the current network tariff structure. This structure, while not strictly ‘cost-reflective’, has historically worked well enough to deliver fair outcomes for consumers — until rooftop solar was adopted en masse, introducing substantial cross-subsidies.

Current network tariffs are structured in such a way that DNSPs recoup 60-75% of their costs from variable usage charges rather than fixed charges.[71] This general structure is passed on to consumers by retailers through variable retail tariffs and fixed daily charges, with network charges making up around half of retail bills.[72] Prior to the broadscale adoption of rooftop solar, relying on usage as a proxy for calculating network charges was a relatively fair way of spreading network costs across the customer base, as a customer’s overall usage was highly correlated with their peak demand in previous decades.[73]

But with current levels of rooftop solar penetration, these network tariff structures — including single-rate and time-of-use — fail to accurately reflect the costs of serving each customer. Charges are predominantly based on usage occurring outside times of critical peak demand. This enables solar customers — who can greatly reduce their consumption during non-critical-peak times — to receive outsized savings, despite not providing material savings on distribution network costs by reducing forecast critical peak demand, as outlined in Section 5.1.

6.3 Rooftop solar: reverse Robin Hood

The cross-subsidies from those who have rooftop solar to those who do not is a form of ‘reverse Robin Hood’; taking from the poor to give to the rich. This is largely because it is much more difficult for apartment owners and renters to install rooftop solar than those who own a house, and apartment owners and renters tend to be less wealthy than house-owners.[74]

The current cost-of-living crisis has brought to the forefront the inability of many households to pay their electricity bills, particularly those on lower incomes. From 2022 to 2023, as network costs increased, there was an 18% increase in the number of customers struggling to pay their electricity bills.[75] Over 250 households were disconnected every week during the 2022-23 financial year and a 2023 survey of NSW households found more than half of disconnected households earned less than $80,000 a year before tax.[76] Rooftop solar cross-subsidies are an added burden for many consumers that are already struggling to pay their electricity bills and avoid disconnection.

Rooftop solar cross-subsidies also represent a wealth transfer from younger generations to older generations. Less than half of those aged 25 to 34 are homeowners, indicating that most young people will be paying cross-subsidies to older rooftop-solar owners, since renters are much less likely to install rooftop solar.[77] This is confirmed by a 2017 Ausgrid survey, which indicates rooftop solar ownership skews towards being older, generally between 54 to 72 years old, while those without solar are more evenly spread in age.[78] A 2024 study also found that the more millennials (aged 25 to 40 at the time of the 2021 census) living in a postal area, the fewer the number of rooftop solar units.[79] Eliminating these cross-subsidies is therefore necessary to end the ‘reverse Robin Hood’ disproportionately affecting less wealthy and younger households.

7. Export charges will not end cross-subsidies

One solution to the rooftop solar dilemma being implemented by some DNSPs is the introduction of two-way export tariffs. This involves charging and rewarding customers for rooftop solar exports during low and high demand periods, respectively. Theoretically, this should reduce the amount of solar being exported into the grid when there is not enough demand to soak it up, while encouraging exports that can help meet peak demand. This may reduce upgrade costs caused by oversupply of rooftop solar exports on sunny days — if the price signal is passed on in retail offers, for which there is no guarantee. But even if export tariffs were passed on to solar customers, they can only reduce the existing cross-subsidies, not eliminate them entirely. Rooftop solar customers will still be able to receive substantial outsized savings on their bills, which will particularly benefit those with smaller systems and higher rates of self-consumption.

7.1 Two-way export tariffs introduced, but not everywhere

DNSPs in some states have considered two-way export tariffs but are yet to introduce them. Queensland’s Ergon Energy and Energex contemplated two-way export tariffs but ultimately decided to defer their introduction beyond 2030.[80] Similarly, TasNetworks and NT’s Power and Water Corporation are yet to exhaust export hosting capacity so have also deferred introducing two-way tariffs.[81] While ACT’s DNSP Evoenergy submitted two-way pricing for residential customers in its draft 2024-2029 tariff structure proposal to the AER, it later removed two-way pricing from its proposal, citing “significant costs and implementation complexity of residential export tariffs within its billing system”.[82]

DNSPs in other states have not yet even considered introducing two-way export tariffs. WA’s Synergy and Horizon Power have introduced different export reward tariffs for peak and off-peak periods but are yet to introduce two-way tariffs.[83] In Victoria, minimum feed-in tariffs rewarding solar customers for exports are set by the Essential Services Commission, which is yet to introduce two-way tariffs. However, the flat minimum feed-in tariff rate is already comparatively low at 3.3 c/kWh in 2024-25 and will drop to almost nothing at 0.04 c/kWh in 2025-26, with variable off-peak rates also dropping significantly from 2.1-2.8 c/kWh to zero.[84] If this trend continues, a charge period may be introduced in future.

NSW and South Australia are the only states in which all DNSPs have introduced or are in the process of introducing two-way export tariffs, as outlined in Table 3.[85] These tariffs are meant to improve ‘fairness’ for consumers, particularly to ensure those without export-enabled rooftop solar or batteries do not pay more than they should.[86] The charges for exports above a free threshold during peak solar hours are meant to help cover the costs of increased stress on the grid, with rewards incentivising customers to shift exports to evening peak times — typically by investing in a battery.[87]

Table 3. Two-way export tariff charge and reward rates for NSW and SA DNSPs

7.2 Rooftop solar owners continue to earn outsized savings under two-way export tariffs

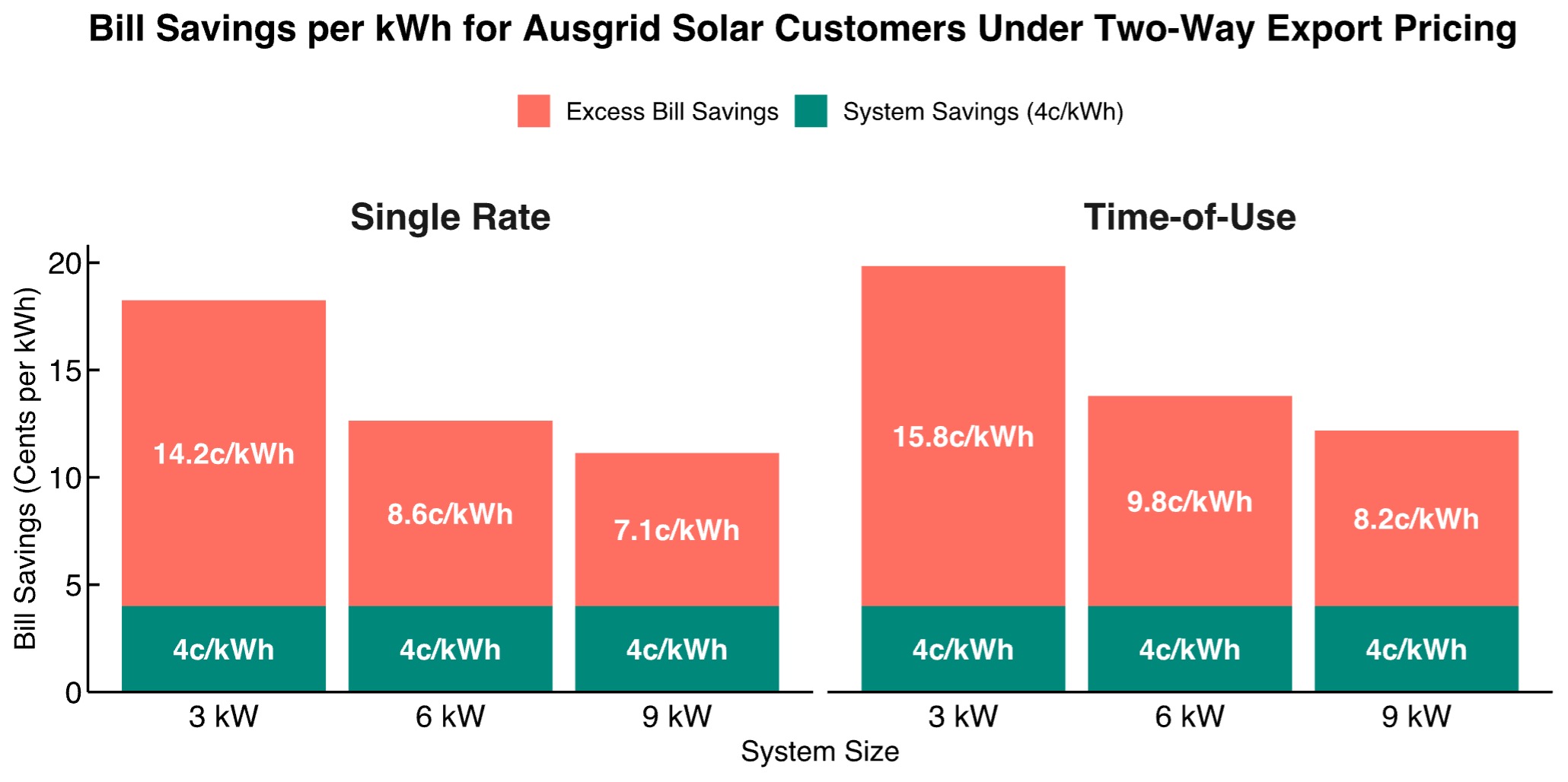

CIS tested the effect on solar customers’ bill savings if retailers were to directly pass on the two-way export tariffs being implemented by Ausgrid, the largest DNSP in Australia (see Appendix 11.4 for methodology). Under the current tariff structure, Ausgrid solar customers save on average 14–24 c/kWh of solar generation from self-consumption and exports — 3.5 to 6 times the value their solar output provides to the grid (Figure 6). This translates to an average annual bill saving of $705 to $1,186 more than is deserved (Figure 7). If Ausgrid’s two-way export tariffs were passed through directly to consumers while usage rates remained the same, overall savings would drop only slightly to between 11 and 20c/kWh (Figure 6), translating to a total of between $538 and $617 in excess bill savings (Figure 7). This shows export tariffs are a step in the right direction and will help reduce solar cross-subsidies, but are too soft a measure to eliminate them entirely.

Figure 6. Average annual bill savings per kWh for Ausgrid rooftop solar customers on both single rate and time-of-use retail tariffs remain substantially higher than electricity system savings from rooftop solar generation (4c/kWh) when two-way export tariffs are applied regardless of system size. Curtailed solar energy arising from the introduction of export tariffs has been excluded from customers’ total solar generation.

Figure 7. Average annual bill savings for Ausgrid rooftop solar customers on both single rate and time-of-use retail tariffs remain substantially higher than electricity system savings from rooftop solar generation (4c/kWh) when two-way export tariffs are applied regardless of system size. Curtailed solar energy arising from the introduction of export tariffs has been excluded from customers’ total solar generation.

The trend of bill savings per kWh decreasing with system size is reversed for total bill savings. This is because smaller systems have lower export ratios (see Figure 10 in the Appendix). A 3 kW system saves consumers more on a per-kWh basis than a 6 kW or 9 kW system because a greater proportion of generation is being self-consumed and therefore saving averted usage rates — which are currently much higher than export rates. However, the greater volumes of generation from larger systems translates to higher total bill savings arising from increases in both exports and self-consumption.

After two-way export tariffs are implemented, the trend of increasing total bill savings with increasing system size is greatly diminished. This is because the higher export ratio of larger systems means most of the kWh being produced are not able to be self-consumed, so a large proportion of the kWh that would have been exported must be curtailed, attracting no savings. This suggests consumers will likely opt for smaller system sizes for new installations and replacements if retailers pass through export tariffs.

The analysis assumed solar customers would curtail any exports above the free threshold during the charge period rather than face charges. However, even if customers do not curtail exports and instead incur charges for excess exports, this would amount to only a small reduction on their overall bill savings of $0, $16 or $45 for 3 kW, 6 kW and 9 kW systems, respectively.

This analysis assumes all retailers pass on the price signal of export tariffs to customers. However, this is not guaranteed as some retailers have already indicated they wouldn’t be passing the cost along on a consumer-by-consumer basis, and instead would spread costs across their customer base — effectively continuing existing cross-subsidies for rooftop solar.[88]

Notably, the ISP’s assumed four-fold increase in rooftop solar by 2050 depends on sustained growth in average system size.[89] Both consultant reports used as inputs for the ISP’s rooftop solar forecasts predict further increases on the current average size for new systems of around 8 kW, with CSIRO’s forecast peaking around 9 kW,[90] while GEM’s forecast continues to grow to almost 12 kW by the mid-2050s.[91] If export tariffs are passed through to customers by retailers — or cross-subsidies from non-solar customers are otherwise significantly reduced or eliminated — these projections are highly unlikely to eventuate. This is because solar customers expect a return on their investment, as shown in Section 3, and these changes would only serve to reduce the optimal system size for the average customer.

DNSPs implementing export tariffs will not end cross-subsidies, as rooftop solar owners will continue to earn outsized savings through self-consumption, even if retailers do pass through the two-way tariff structure. While export tariffs are a step in the right direction, more radical network tariff reform is required to reflect the true value of rooftop solar to consumers.

8. Batteries will not lead us to paradise

Batteries have often been portrayed by renewables advocates as the silver bullet that will solve the network problems caused by rooftop solar and help secure an energy paradise for all. The Prime Minister has even used the supposed financial benefits of rooftop solar and home batteries as evidence that large-scale solar and batteries will benefit the economy.[92] But, as with rooftop solar, the availability of batteries for reducing critical peak demand is not guaranteed — and if it were, consumers would likely end up paying more to battery owners than they would save from any battery-induced reduction in network upgrade costs.

With the advent of export tariffs, some rooftop solar owners — 1.6% as of 2022[93] — are buying home batteries to allow them to store their solar energy for exporting back into the grid during peak hours.[94] This helps ensure they receive greater rewards and avoid charges in the two-way tariff system. However, many environmental and consumer groups have called for existing rooftop solar subsidies and rebates to be extended to home batteries.[95] This is because, for most rooftop solar owners, batteries are unaffordable and show no signs of getting cheaper any time soon.

AEMO’s ISP assumes a 30-fold increase in consumer batteries connected to the grid by 2050,[96] but one analysis suggests this would cost $20,881 per customer.[97] Even the GEM battery forecast, which is used as an input to the ISP, concedes that home batteries are “yet to reach levels of financial attractiveness… that would support mass-market uptake”.[98] The GEM report cites one of the underlying drivers of its forecast increase in battery uptake over the next several years as consumers having “a misapprehension that the battery will leave them financially better off or at least shield them from what they believe will be further large rises in electricity prices”.[99] In other words, it assumes a material proportion of consumers will buy batteries that will not benefit them financially.

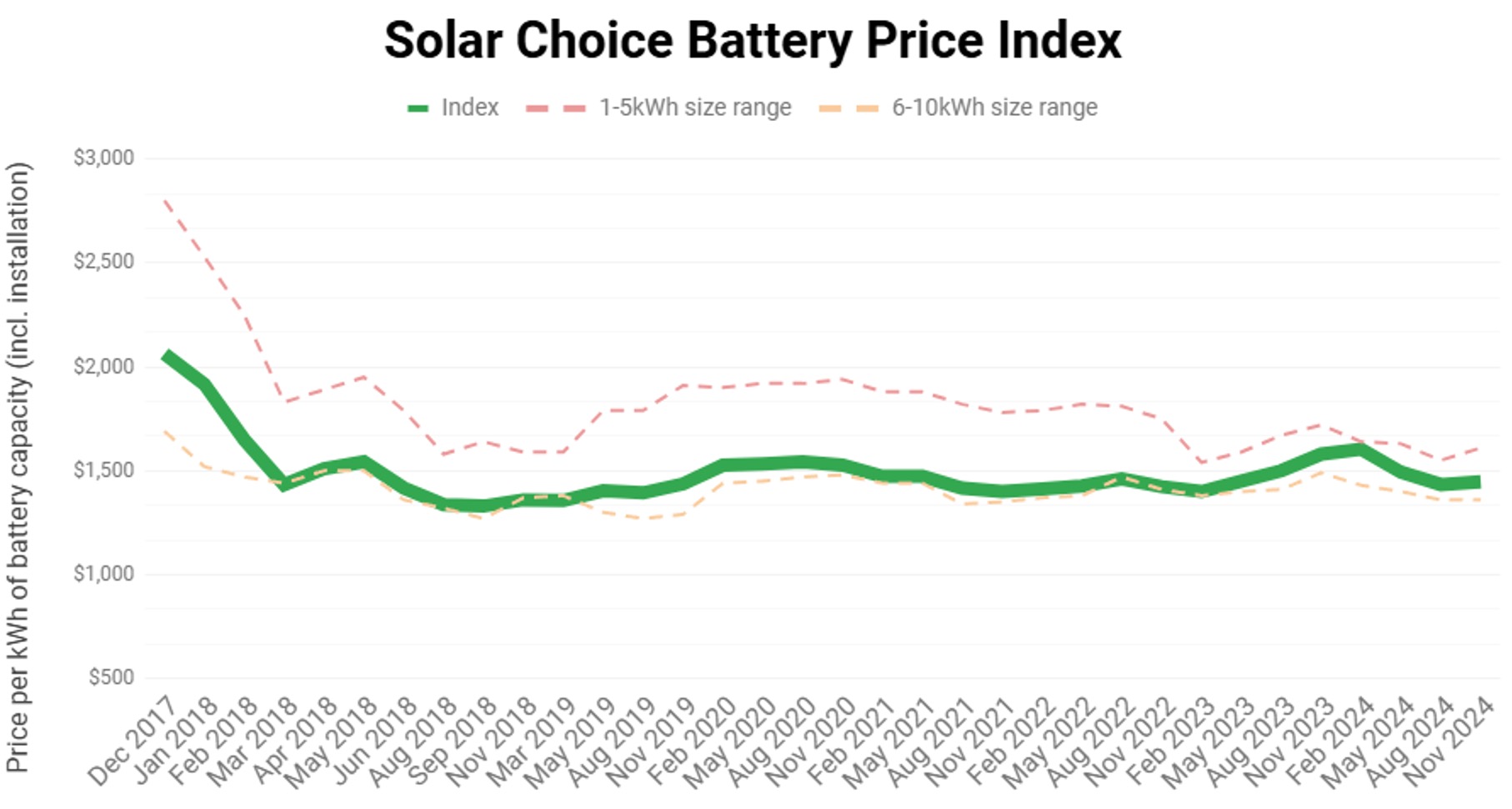

The GEM report’s forecast accelerated uptake of battery systems from 2026 onwards depends on the assumption that the federal government will provide rebates equivalent to half a battery’s value.[100] Concerningly, GEM has not provided an estimate of the cost of its assumed government subsidies. The report also assumes battery prices will fall dramatically in future, citing “a halving in costs… as a rule of thumb for an inflection in uptake”, with this occurring between 2023 and 2030.[101] The AEMC’s research is even more optimistic, pegging 2025 as “the year domestic batteries reach the affordability tipping point”.[102] But such price falls are far from guaranteed. According to the Solar Choice Battery Price Index, prices have remained flat for the past six years, as shown in Figure 8.[103]

Figure 8. Solar Choice Battery Price Index showing home battery prices remained relatively flat from 2018 to 2024.

Consumers who cannot afford batteries have also argued that the government should provide subsidies, given the government encouraged consumers to install rooftop solar in the first place. As one Queenslander said, “It’s getting super expensive to have a [rooftop solar] system, but I’m not getting any help from the government to permit me to use that system to its fullest benefit, whilst helping the government and AEMO and electricity retailers manage the grid.”[104] Senator David Pocock expressed a similar sentiment from rooftop solar owners in the recent Senate inquiry:

One of the concerns I have raised with me is that people make these [rooftop solar] investments. They are generating electrons just like the big power plants and yet they would be having dynamic pricing forced on them without any notice by some of the retailers. At times they are having their feed-in constrained.[105]

This illustrates the political problems that arise when governments, energy market bodies and industry players all tell consumers that investing in rooftop solar will usher them into a paradise of lower bills while helping reduce costs and emissions for the rest of the grid. Consumers have been given a distorted picture of what their investments are doing to the grid. As illustrated in Sections 4 to 6, the benefits of rooftop solar have been massively oversold — not all electrons deserve the same compensation. Large-scale, dispatchable plants provide stability and reliability to the grid while rooftop solar reduces stability and reliability of supply. As rooftop solar installations increase, the competition between neighbouring solar systems that are perfectly correlated in output becomes fiercer, further eroding the value of rooftop solar generation and putting pressure on the grid. This then drives DNSPs to reduce rewards for exports and increase charges. Consumers have been left feeling betrayed and entitled to further government handouts in the form of battery subsidies.

8.1 State government battery subsidies have largely failed to increase uptake

Most state governments have already introduced subsidy programs for batteries, with some having since closed with no signs of re-opening. The number of batteries installed under these programs amount to little more than a rounding error when considering the total number of solar customers in each state, and the number of solar systems continuing to be installed every year. AER data from 2023-24 indicates only 4% of export customers used batteries in conjunction with their solar systems and only 16% of new export-enabled solar systems incorporated a battery.[106] As AEMC Chair, Anna Collyer, said in a recent speech:

At the end of 2023 around 250,000 Australian households and small businesses had installed batteries. That’s a strong number, but nothing like the 3.7 million rooftops currently sporting solar panels. There’s still a long way to go for domestic batteries to significantly soak up the glut of solar we see in the middle of many days.[107]

The SA government introduced a Home Battery Scheme in 2018, offering a $6000 subsidy eventually wound back to $2000 before being scrapped in 2022 by the newly elected government.[108] As then-new Energy Minister Tom Koutsantonis explained, the program had “minimum uptake and follow-through” and “has not even reached half of its targeted 40,000 homes” because “the market signals weren’t working, there wasn’t sufficient money left to meet the target”, insisting “you’ve got to reach a point where you say ‘this has failed so we’re getting out’”.[109] The government’s own online calculator estimated a rooftop solar owner with a 10 kW system would lose around $1200 and $2300, respectively, by purchasing a 6 kWh or 10 kWh battery, even including the subsidy. Larger battery sizes provided only marginal benefits for consumers, of around $700 in value for a 10 kWh or 14 kWh system.[110]

The Queensland government also introduced a subsidy of $3000 to $4000 for low-income earners to purchase a battery for solar systems in February 2024 but closed the program only a few months later in May.[111] The government has not revealed how many batteries were installed under the program, but as the $16 million funding allocation appears to have been exhausted, about 4,000 to 5,300 batteries were likely subsidised.[112] This represents at most 1% of the more than 460,000 Queensland consumers who exported solar power in 2023-24.[113] Queensland’s newly-elected Coalition government has made no mention of any plans to revive the program.

As part of the Solar Homes Program, the Victorian government started offering solar battery rebates of up to $4,174 in 2019.[114] However, in 2023 the government switched to offering Solar Battery Loans of up to $8,800 to be repaid over 4 years.[115] The government has acknowledged that “adding a battery to an existing solar PV system is a significant investment, and for some households the outlay might be more than what you save on energy bills over the life of the battery.”[116] From the launch of the initial battery subsidy in July 2019 to November 2024, 18,534 batteries have been installed under the Solar Homes Program.[117] However, as of the end of 2023-24, the proportion of exporting solar customers in Victoria with a battery remains below 3%.[118] The Solar Homes Program also provided rebates of up to $1,400 on almost 300,000 solar panel installations over the same time period.[119] This means rooftop solar installations have outpaced battery installations 16:1 under the government’s scheme, which will worsen cross-subsidies and increase pressure on the grid from oversupply of solar. Foundational weaknesses of the program were highlighted in a damning report by the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office in 2021:

DPC’s Solar Homes Program Design and Options Report was insufficient to lay out and make the case for government intervention. It was not a business case and did not explain why the best solution to the identified need of reducing Victorians’ energy costs is rebated solar photovoltaic (PV) panels, batteries, and solar hot-water systems… DPC also did not consider the ‘do nothing’ option as a benchmark for assessing the program’s value proposition despite existing growing demand for solar PV panels and the potential adverse impact of accelerated solar PV panel uptake on the state’s electricity grid.[120]

The Tasmanian government also offers loans up to $10,000 under the Energy Saver Loan Scheme, covering a range of “energy efficient products”, including batteries.[121] From its inception in October 2022 to January 2025, the program supported the installation of less than 200 batteries[122] — a mere 0.4% of the more than 49,000 Tasmanian customers who exported solar power in 2023-24.[123]

Following the introduction of export tariffs by DNSPs, the NSW government responded by introducing a home battery subsidy of $1600 to $2400 for rooftop solar owners, as well as a $250 to $400 incentive for connecting to a VPP from November 2024.[124] Given the track record of battery subsidy programs in other states, it seems unlikely the latest NSW attempt to increase uptake will make much of a difference.