Home » Submission to the Inquiry into financial regulation and home ownership

Contents

- Summary and introduction. 3

- General principles and the role of regulation. 4

- Specific Regulations. 5

- Evaluation. 8

- Security of tenure. 9

Regulation of the financial system is needed to protect depositors and avoid financial crises. However, current financial regulations go beyond these legitimate objectives to prevent mutually advantageous loans. Consequently, households without wealth are denied access to finance. Worthwhile investments and access to home ownership are blocked. Financial regulations exacerbate social inequality and limit economic opportunity.

The CIS believes financial market regulation should be less intrusive. Borrowers and lenders, not bureaucrats, should be responsible for deciding whether a loan is ‘suitable’. Broad neutral instruments that protect systemic stability, such as capital requirements, should be used instead of the detailed specification of loan conditions. We should remove obstacles to market mechanisms such as futures markets and fixed-rate mortgages, which efficiently provide security and stability. Lighter regulation would lead to more innovation, investment, equality of opportunity and lower costs to borrowers.

Although financial liberalisation is desirable, the timing is complicated. Obstacles to housing finance reduce housing demand. However, there are currently even greater obstacles to housing supply, in the form of zoning restrictions. Hence, there is excess demand for housing and a crisis of affordability. While removing obstacles to housing demand is desirable in the long run, we need to fix supply first. This involves loosening zoning restrictions, as the CIS has discussed in previous parliamentary submissions (CIS, 2021, 2023). Otherwise, the affordability crisis will worsen.

This submission focuses on regulations that impede housing finance. The CIS has discussed taxation of housing in previous parliamentary submissions; in particular, Section 3 of our submission to the Falinski Inquiry. We addressed the issue of accessing superannuation for housing in an earlier submission to the Senate References Committee. We do not repeat this discussion.

When a financial institution fails, the failure can spread to other institutions, through confidence effects and cascading defaults. In 2008, 1990, 1930, and 1893, multiple bank failures in Australia and overseas had catastrophic consequences. These externalities provide a sound reason for capital requirements and stress testing to ensure an “unquestionably strong” financial system.

However, many of our financial regulations have little bearing on systemic risk. They seem primarily focused on preventing lenders and borrowers from agreeing to risky loans.

The prevention of risk and failure may be legal, but they are not the appropriate objectives of financial regulation. The freedom to fail is a foundation of our market economy. If lenders and borrowers are prevented from making their own assessments of which investments are worthwhile, our economy will be less prosperous. If an individual borrower or shareholder takes a risk that does not pay off, and bystanders are not harmed, that is their responsibility.

Paternalism can be justified under certain circumstances. In particular, the government plays a role in preventing harm to those who may not understand the commitments they make, such as children. It also has a role in preventing misleading or deceptive conduct. It is more controversial whether the government should discourage borrowers from making decisions they will later regret, although limiting finance for gambling seems to have broad public support.

However, “responsible lending” restrictions go well beyond these defensible limits. Regulators require detailed information on household expenses before allowing many loans. There is no clear public benefit in these restrictions. Media advice on how to game the restrictions is common, indicating that they are an onerous burden to be bypassed, not useful guidelines.

If the regulators know something that the borrower and lender do not, it should share that information. It is useful for the government to tell borrowers that their loans may not be suitable. And, in particular, to provide warnings of the sort “Your proposed deposit would be inadequate to cover a once-in-a-decade fall in house prices, leaving you in negative equity” or “if interest rates rise x%, you would no longer have the cash-flow to fund expenses A, B and C”. However, if the borrower and lender are willing to take that risk – with the higher insurance payments and interest rate it might involve – it is difficult to see who is better off by preventing the loan.

More broadly, there is a useful role that the government should play in the provision of advice and technical information, as for example, it does in health and road safety. Many investors are unaware of the benefits of equity index funds, or of diversification more broadly. Many home buyers have an exaggerated view of their financial return relative to renting. Many borrowers of ‘payday’ loans, ‘buy now, pay later’ and credit card debt do not realise how quickly compound interest accumulates. Borrowers on high mortgage rates do not refinance. And so on.

ASIC’s https://moneysmart.gov.au/ web site provides a good building block that should be expanded. Moreover, warnings should be given in clear concise form — unlike product disclosures — before potentially risky financial decisions. Simple measures like this would be preferable to many of the intrusive borrowing restrictions currently in place.

High deposit requirements

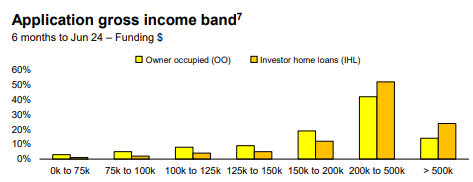

Restrictions on housing finance have made home loans the preserve of the rich. The chart below shows Commonwealth Bank mortgages by income. Almost all the lending goes to the highest income earners with those on low and moderate incomes being locked out. This skew has increased dramatically over the past few years. The share of loans going to borrowers with income over $200,000 has approximately doubled since 2018 while the share going to borrowers with income less than $100,000 has almost halved.[1]

Source: Commonwealth Bank, 2024

High deposit requirements reserve finance to those who are already wealthy. In particular, they place home-ownership out of reach of those without wealthy parents. They are making home-ownership hereditary.

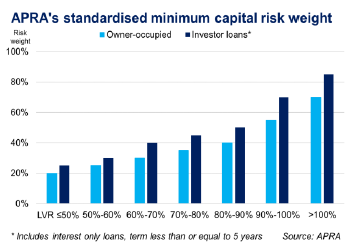

APRA says it has no formal high deposit requirements. Informal requirements are difficult to assess or quantify. A major instrument is capital requirements. As shown in the chart below, the risk weight on low deposit loans is very high, meaning that banks must finance these loans with expensive equity, whereas high deposit mortgages have a low weight and can be financed with less costly debt.[2]

To borrow with a low deposit requires lenders mortgage insurance, or LMI. According to https://www.savings.com.au/home-loans/lenders-mortgage-insurance, LMI on a $600,000 loan is about 1% with a 15% deposit, 2% with 10% or 4% with 5%. Estimates from https://www.commbank.com.au/digital/home-buying/calculator/stamp-duty-calculator?ei=tools_totalcost are not very different.

Reflecting the harm these barriers do; state and federal governments are increasingly providing subsidies to borrowers unable to meet the deposit requirements. For example, via home guarantee and shared equity schemes. We seem to have two sets of policies designed to offset each other. One set of policies blocks high-risk borrowers while another set subsidises them. It would be simpler to allow the market to decide which risks are worth taking. These contradictions arise when policy is based on vibes and shifting public pressure instead of a clear description of market failure, a point elaborated upon below.

The interest rate buffer

APRA requires that assessments of whether borrowers can repay their mortgage assume that interest rates rise 3 percentage points. APRA says, “The buffer provides an important contingency over the life of the loan for unforeseen changes in a borrower’s financial circumstances.” That is, it is designed to reduce individual, not systemic, risk. It is easy to see, in principle, how individual borrowers might get in trouble if interest rates rise by more than 3%. It is difficult to see how the financial system might be threatened. Individual risk is not APRA’s responsibility.

The buffer is standard paternalism. Individual lenders should be able to set their own buffers. We should allow and encourage innovation and differing lending policies.

The buffer seems to be too high. A well-calibrated buffer would show substantial defaults for borrowers near the threshold after a 4-percentage-point increase in mortgage rates. That has not happened. In June 2024, only 1 per cent of banks’ housing loans were non-performing. And there has been no discernible threat to systemic stability. Which leads to the inference that APRA denied homeownership to many borrowers who would have been willing and able to service their loans.

Moreover, the buffer has a serious design flaw. It applies to all loans, including those on fixed rates, even though those rates cannot rise.[3] This is compulsory protection against a risk that cannot occur.

It might be argued that interest rates can rise after the period at which rates are fixed. However, assessments of capacity to pay 5 years or more into the future have little predictive power. Defaults after 5 years are uncommon, and a risk that can be foreseen several years in advance is one that the borrower and the market can avoid. Risks after 5 years are probably tiny and non-systemic and certainly smaller than the risk applying to variable rate loans.

If the buffer is to be maintained, it should be proportional to the share of the mortgage at variable rates over, say, a 5-year horizon. So, a borrower who fixed all their rate for 5 years would not have a buffer. A borrower who fixed all their rate for only 2 years, or who fixed 40% of their mortgage for 5 years, should only have a buffer of 1.8% (= (1-0.4) x 3%). Such a rule would mean that borrowing capacity would increase with the amount of a mortgage at fixed rates. So, this would increase borrowing and the demand for housing.

Fixed rate mortgages

Removing obstacles to fixed-rate borrowing would have other advantages. It would make household balance sheets more stable. It would reduce bankruptcies and other financial stresses when interest rates rise during the cycle. It would make tightening monetary policy less politically fraught. For these reasons, it would be desirable to give fixed rate mortgages a lower risk weight than variable rate loans, proportional to the duration of the fixed term.

A common argument against fixed rate mortgages is they would make monetary policy less potent. This concern assumes that the household cash-flow is an important channel of monetary policy. However, in empirically-estimated models of the Australian economy, most notably the RBA’s MARTIN, household cash flow is less important than net exports, investment, housing construction, wealth, and other channels of transmission (Gross and Leigh, 2022, Figure 2). Consistent with this, monetary policy is estimated to be more potent in the United States, where 30-year fixed rate mortgages are standard.[4]

Housing Price Futures

The risks of house price fluctuations, to both borrowers and lenders, could be substantially reduced by hedging on house price futures markets. Buying and selling house price futures enables traders to lock in a future price, reducing the risk of unwelcome price movements. That should reduce deposit requirements. Futures markets also provide valuable information.

Futures markets make bubbles less likely. In the presence of futures markets, traders who think prices are unsustainably high can short the market. That is, offer to sell at a future price that they expect will exceed the spot price. In doing so, the bubble is deflated before it gets going. However, when futures markets are missing, would-be short sellers are not able to trade on their views. The market is over-represented by optimists who think prices will keep rising, a sentiment that can be self-reinforcing. (Noussair, Tucker and Xu, 2014).

While the evidence is mixed, most studies of futures markets have found them to have a stabilizing effect on prices (de Jong, Sonnemans and Tuinstra, 2022).

In Australia, traders who expect house prices to fall may short bank shares as a substitute. Shorting of bank shares can reduce confidence in the bank’s viability, become self-fulfilling and destabilise the financial system. Partly for this reason ASIC prohibited short-selling banks in 2008.

It is sometimes objected that “no-one wants to take the other side” of a house price futures contract. However, there will be a price at which the other side is attractive. This may involve the trade becoming indistinguishable from insurance, as happens with floods, car theft etc.

Advocates of house price futures have called on the government to pay for some of the transaction costs that make the market illiquid. However, a better approach would be to reduce the risk weight on mortgages that are hedged. Risk weights should be on portfolios, not assets.

The Counter-Cyclical Capital Buffer

The risks of bank failure change over time, as asset prices and credit growth evolve. If one accepts that capital requirements are costly, then their appropriate level should also change with evolving risks. This is the rationale for the Counter-Cyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB). Research suggests that the CCyB is a more cost-effective instrument for stabilising the financial system than interest rates or other prudential controls.

In practice, APRA has rarely varied the CCyB. In part, this may reflect its reliance on an extensive list of financial stability indicators — a “heat map” approach. Many of these indictors have little empirical relationship with financial stability. The result is confusion-driven paralysis.

Monetary policy suffered the same confusion when it was guided by a “checklist” in the 1980s. After reflecting on what indicators mattered and what did not, the RBA, like foreign central banks, settled on flexible-inflation targeting.

For similar reasons, the CCyB should respond to a smaller set of empirically tested indicators. That would probably include credit and house prices. There is substantial research on how those indicators should best be measured. For example, the CCyB should respond to the bubble component of house price movements, not the fundamental component. Both the level and growth in credit have been shown to have predictive power for financial stability.

The rationale for APRA’s policies discussed above is unclear. It is not an organisation that explains itself clearly. In particular, the relevant market failures and the quantitative effect on systemic risk are not explicit.

This opacity applies more broadly:

- APRA and ASIC discourage interest-only loans and lending to investors. Why? Default rates on these loans are not especially high. And even if they were, why would a higher interest rate not be an appropriate and sufficient response? How do restrictions like these reduce systemic risk at lower cost than higher capital requirements?

- In the recent past, APRA has imposed restrictions that seriously undermine market competition. Quantitative restrictions on investor lending (to 10% annual growth) and interest-only loans (to 30% of total mortgages) effectively enforced a cartel.

- Responsible lending restrictions prevent borrowers with changed circumstances refinancing their mortgage at a lower interest rate. In August 2024, 69% of mortgage brokers said they have clients in “mortgage prison” (MFAA, 2024).

In none of these examples was a serious public explanation provided. If a frank and honest discussion of costs and benefits had been provided, foolish polices would have been less persistent.

Restrictions like these should require cost-benefit justifications. Financial regulators in other countries do this — see, for example, Firestone, Lorenc and Ranish (2019). Admittedly, it can be difficult to assemble an evidence base for new regulations before they are implemented. So there should be a requirement for regular review and evaluation. This is now government policy, being applied throughout the public service (Leigh, 2023). This would require an expansion of APRA’s research capacity.

APRA’s alternative of superficial, vibes-based justifications leads to restrictions that preference politically favoured groups, are not commensurate with the risks, and are not targeted at a clear market failure.

Many governments in Australia are implementing or considering regulatory changes to improve security of rental tenure. However, the underlying problem is one of taxation, not regulation.

Insecurity of tenure and the associated lack of control are large problems in the rental market. Disruptive, costly evictions are common. This insecurity is a leading reason people prefer owning to renting.

A major reason for this insecurity is that we have the wrong landlords. Most of our landlords own one or two properties. Because those properties constitute a large share of their wealth, owners wish to keep them liquid, so will only offer short-term leases. More importantly, their financial conditions often change, so they churn. Most landlords and rental properties exit the sector within five years (Martin et al, 2022).

In contrast, in Europe and the United States large corporations own a large share of the rental stock. It is common for apartment buildings to have a single owner. Long leases are common and evictions due to landlord turnover are rare.

An important reason for the rarity of corporate landlords in Australia is progressive land tax. The chart below shows average land tax rates rising with land values in NSW, Victoria and Queensland, the three states with the highest proportion of apartments.

The owner of one moderately large block of flats would often be liable for the highest marginal rate of land tax, 2% in NSW, 2.65% in Victoria and 2.25% in Queensland. Land values might comprise about 17% of the cost of a Sydney apartment[5]. So, the highest rate of land tax would be 0.34% of the property value. Given that net rental yields are about 1.7%,[6] the land tax accounts for 20% of net rental income. This is a cost that single-property landlords do not need to pay. Accordingly, they outbid multi-property landlords and most of our rental stock is owned by single-property landlords. Churn and insecurity are the result.

Regulatory reform of tenancy law will never generate security of tenure while our rental stock is mainly owned by small investors. We need to remove the progressivity of land tax.

Endnotes

[1] As this submission was being finalized, we notice that this data is discussed in more detail in the Barrenjoey submission.

[2] As an aside, note that capital requirements are higher for rental properties than owner-occupied, which is reflected in loans on rentals having a 40 basis point higher mortgage rate. This financing bias compounds the anti-rent bias in the tax and welfare system, including the exemption of land tax, capital gains tax, tax on imputed rent and exemption from the old age pension means test for owner-occupied housing.

[3] AFCA (2024, p24) say it “is not generally necessary for firms to apply buffers to loans which have a fixed interest rate for their entire term”, however our discussions with industry participants say the 3% buffer is applied to home loans with fixed rates.

[4][4][4] The US Fed (Table 3) estimates that a percentage point reduction in the federal funds rate boosts US GDP by 1.2 per cent after two years. In contrast comparable modelling estimates by the RBA (Figure 12) suggest an effect about a third smaller in Australia.

[5] According to the CIE, 2024, a representative Sydney apartment sits on $150,000 of land and sells for $885,000. That estimate is conservative.

[6] Fox and Tulip, (2014, Tables A1 and A2) estimate a gross rental yield of yield of 4.2%, less running costs of 1.5% average annualized transaction costs of 0.7% and estate agent fees of 0.3%.

Submission to the Inquiry into financial regulation and home ownership