Introduction

This paper is a further developed version of the author’s submission to the Treasury consultation on the federal government’s Better Targeted Superannuation Concessions proposal, lodged in April 2023. The proposal is to add to the existing superannuation tax system a total balance threshold of $3 million, beyond which individuals would be subject to an additional tax on a portion of the earnings of their superannuation balances.

The approach of this submission is in three steps:

- To question the fundamental justification for a new tax measure aimed at increasing superannuation tax revenue and targeting those with large balances;

- To critique the specific design features of the proposal and to canvass improvements in the event that such a proposal proceeds; and

- To suggest different ways to raise additional revenue from superannuation if the government remains determined to do so.

We start with a description of the proposal and the features that break new ground in Australian taxation policy.

The proposal

At the time of writing the details of the proposal are still not known in full. However, enough was revealed at the time of the government’s original March 1 announcement and in subsequent elaboration, that we are able to sketch an outline of the new tax.

The proposal is that beginning with fiscal year 2025-26, every individual’s total superannuation balance aggregated across as many super fund interests as they may have will be tested against a $3 million threshold. For brevity in the rest of this report we call this the TBT for ‘total balance threshold’.

If at the end of a financial year, an individual’s total balance exceeds the TBT, then additional tax will be assessed on the earnings from a portion of the total balance according to the formula:

(Total balance minus TBT)/TBT

Thus, if an individual’s total balance is $4 million, then the proportion is 4 minus 3 divided by 4 equals one quarter. Earnings are defined as the increase in the total balance over the year; whether from interest, dividends, distributions or capital appreciation. Thus, if in our example the balance increased from $3.5 million to $4 million during the year, the additional tax would apply to one quarter of $500,000 ($125,000).

However, the calculation of earnings is to be adjusted to exclude new contributions from the increase in the balance and to add back in any withdrawals made during the year.

The additional tax is to be at a rate of 15 per cent. Thus, in the above example, it would be 15 per cent of $125,000 (assuming for simplification no contributions or withdrawals), or $18,750. This is to apply whether or not the individual’s funds are in accumulation or pension status, and is additional to the existing 15 per cent tax on earnings — which applies to all balances except those up to the Transfer Balance Cap supporting pensions (currently $1.9 million).

The TBT proposal is to be applied to defined benefit interests as well as defined contribution interests.

The Treasury has estimated that the new tax will raise about $2.3 billion a year when it is fully operational, which will not be until 2027–28. The government has set the start date as 1 July 2025 in order not to break a 2022 election promise to keep superannuation taxes unchanged in its first term. However, it plans to pass legislation well before the next election, which means that in the event of a change of government, the new government would have to secure repeal of the legislation for the new tax not to proceed.

The Prime Minister has also said that the election undertaking only ruled out ‘major’ superannuation tax changes, and this is not a ‘major’ change because it affects only a small number of people (0.5 per cent of those with superannuation interests, according to the Treasury).

The proposal raises many points of detail yet to be clarified, such as:

- How assets are to be valued at 30 June each year;

- What happens when earnings as defined are negative; and

- How it can be applied to defined benefit interests when many such interests have no balances and no earnings.

However, the proposal is well-enough defined to be open to critical review. We turn first to the basic justification put forward for the change.

Questioning the basic justification

The fundamental justification for the proposed TBT is built on two propositions:

- That the cost (revenue foregone) of superannuation tax concessions is excessive, particularly in the context of a structural budget deficit.

- That the benefits of superannuation tax concessions are skewed unduly in favour of higher income earners.

These propositions have been repeated so often over so many years that they have become conventional wisdom. The cost figure that became embedded in public discourse used to be $30 billion but is now $45 billion.

The most recent evidence cited in support of a reduction and restructuring of concessions is the Treasury’s Tax Expenditures and Insights Statement (TES) of February 2023. This is a longstanding annual publication but the most recent version has changed the title (from ‘Tax Benchmarks and Variations’).

This seemingly innocuous change reflects an intention to convey the idea that revenue foregone by not taxing everything at full and regular marginal rates is as much an ‘expenditure’ as actual government expenditure. The ‘insights’ part of the title reflects an intention to make the document more analytical and more focused on distributional issues — who benefits from tax ‘expenditures’?

It is no coincidence that the government’s announcement of the new TBT measure came the day after the release of TES.

Another part of the background to the government’s announcement was the Retirement Income Review (RIR) commissioned by the previous government and released in late 2020, which is very much in tune with TES.

However, there is another side to the tax expenditure story told by the Treasury and the RIR.

The TES purports to measure the revenue cost of tax concessions, and in its 2023 update it estimates that superannuation concessions cost more than $45 billion a year — a figure that exceeds the cost of the age pension and is projected to grow further. TES also purports to show that this huge ‘expense’ of lost revenue is skewed in favour of higher income earners.

The RIR also focused on tax expenditure estimates and on the vertical distribution of concessions across income levels; arguing that this distribution was inequitable, with too much of the benefits going to higher income recipients.

The challenge to these tax expenditure calculations is that they use as a benchmark the taxation of super contributions and earnings in the same way a bank deposit is taxed — with full taxation at marginal rates on both the income from which the deposit is made and the interest that it earns. If applied to long-term saving (which is what superannuation is), such an approach to taxation results in extremely high effective marginal rates because of the compounding of earnings and the tax on earnings. This is why it is disingenuous to equate marginal rates on labour income to marginal rates on the income from saving. It is also why the most common policy among OECD countries is to exempt private retirement scheme earnings from taxation and to tax only one of either end-benefits (known technically as the EET arrangement) or contributions (TEE). Australia is one of only three OECD countries that tax both contributions and earnings.

When the Treasury benchmarked super concessions against a TEE arrangement in 2017, the total cost of contributions and earnings tax concessions dropped from $36 billion to $7 billion.[1] Some critics have argued that Australia’s approach to super taxation produces much the same overall result as EET would. The Parliamentary Budget Office recently estimated that a 34 per cent tax rate on either contributions or end-benefits and with no tax on earnings (either TEE or EET) would equate to Australia’s current approach in overall terms. Professor Jonathan Pincus has recently written along similar lines.[2]

This kind of evidence suggests that Australia’s overall tax treatment of superannuation is not excessively generous to the taxpayer. Indeed, the government would appear to agree if all that they are intending to do is clip 5 per cent off the overall concessions through the TBT tax and leave the other 95 per cent in place. However, this tax will bite more severely the longer the TBT remains unindexed; and the government may well devise other measures to curb super tax concessions after the next election.

For the time being, however, the purpose of the TBT tax seems not so much to have a big impact on the overall cost of concessions but to have a big impact on a small number of people with large balances. It is mainly about distribution, which brings us to the second proposition — that the benefits of super tax concessions are skewed unduly in favour of higher income earners.

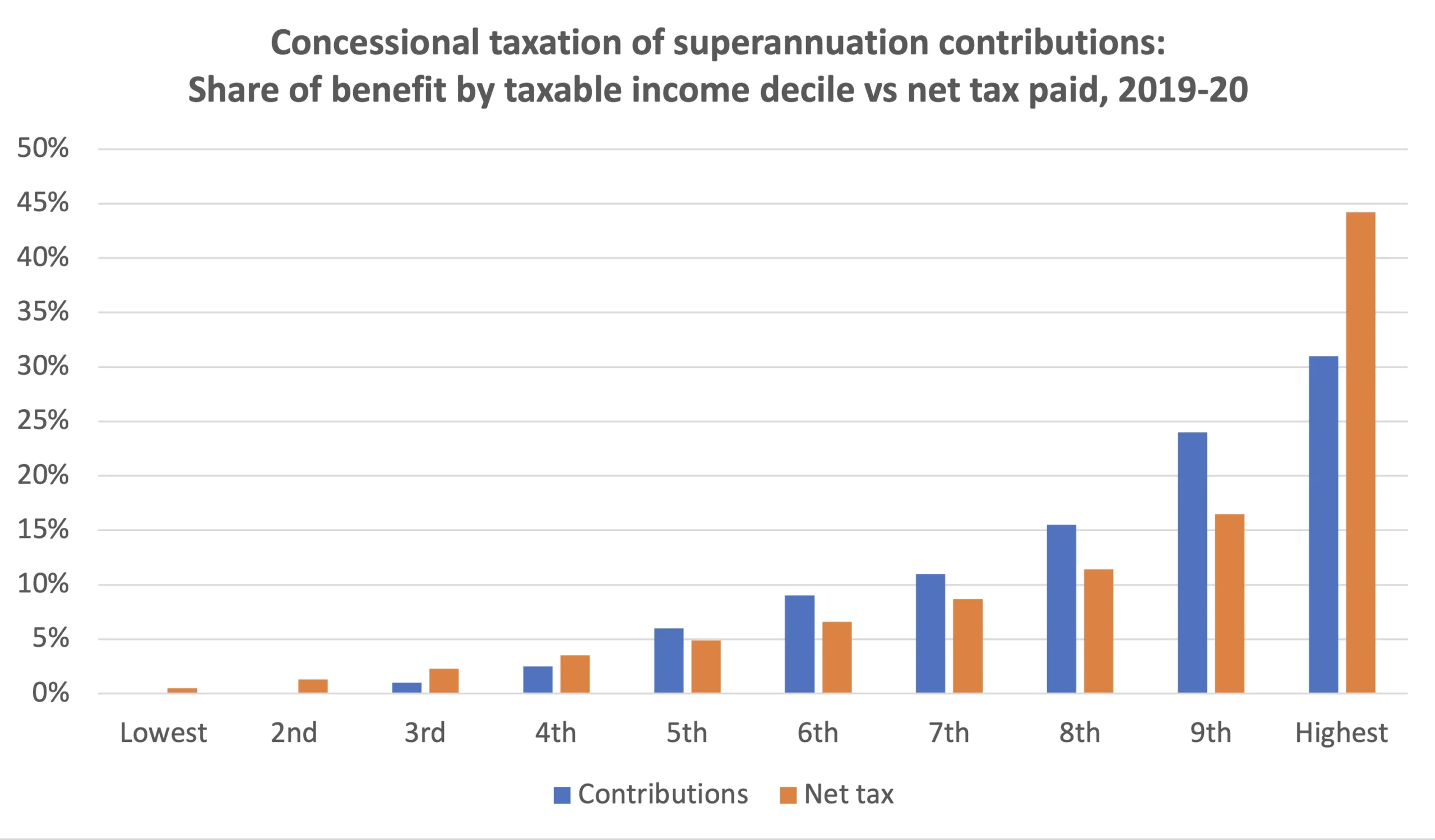

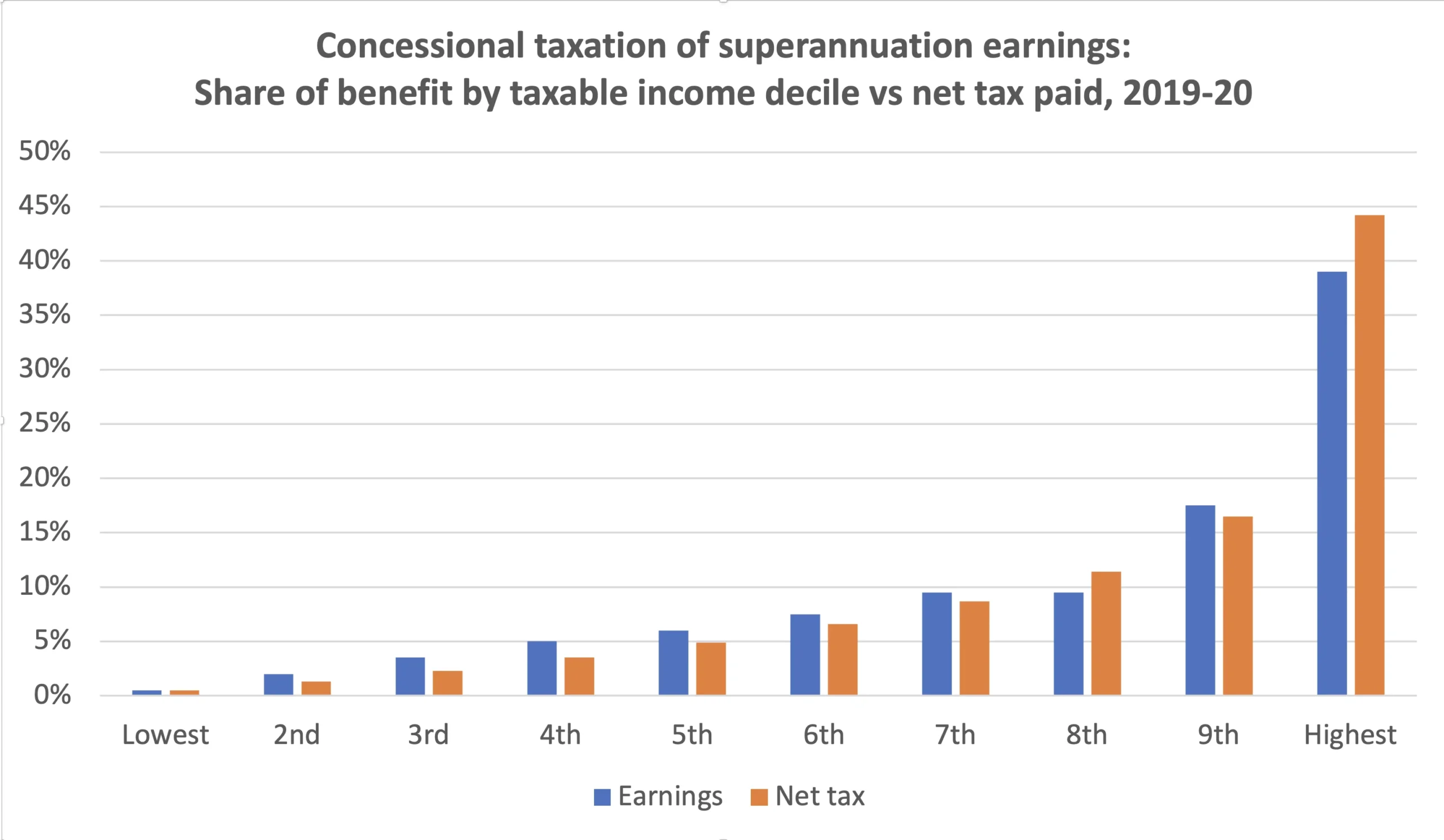

That they are skewed towards higher income brackets cannot be denied. As TES shows, the top 10 per cent of the income distribution receives 31 per cent of the benefit from paying contributions tax below their marginal rate and 39 per cent of the benefit from lower tax on fund earnings. However, should this be at all surprising or objectionable if it is this group that earns a lot of income and pays a lot of tax? This objection to super tax concessions is like the objection to personal income tax cuts that deliver the largest benefits to those with the largest tax bills.

The two charts that follow reproduce the distributional information on contributions and fund earnings tax concessions by income decile as reported in TES, but superimpose the shares of total personal income tax paid in the same year by each decile as reported in the Australian Taxation Office’s Taxation Statistics publication. As these charts show, the top decile’s shares of super tax concessions are in fact below their share of tax paid; and for other deciles, the shares of tax paid and concessions received are fairly close — apart from the eighth and ninth deciles’ shares of the contributions tax concession.

Source:

Tax Expenditure and Insight Statement, Feb 2023, Treasury, pp. 15-17

Taxation Statistics, 2019-20, Australian Taxation Office

Source:

Tax Expenditure and Insight Statement, Feb 2023, Treasury, pp. 15-17

Taxation statistics, 2019-20, Australian Taxation Office

Objections to the distribution of super tax concessions appear to reflect an unstated assumption that these concessions are like a fixed sum of money to be distributed evenly across the population or skewed in favour of lower income super participants — like a social security benefit such as the age pension. However, it is not clear that this has ever been the objective of the super tax system. If instead that objective is to correct for the anti-saving biases in the regular tax system, then a distribution skewed towards those with higher incomes, higher savings, higher super contributions and higher balances is to be expected.

The equity of superannuation taxation can only be properly assessed taking a broad view of taxes and transfers that includes the share of taxation actually paid by the top 10% or 20% of the income distribution, the distribution of the means-tested age pension and related benefits, and the distribution of taxes and benefits over lifetimes.

Moreover, superannuation is but one part of a much larger tax/transfer system, and equity and progressivity should only be judged on the results of that system in its totality, not any one part of it.

For all these reasons, the new tax should be shelved. It is piecemeal policy change with no connection to broader tax reform. Superannuation tax should not be left out of tax reform; but the time to reconsider it is in the context of broader tax reform, if and when that occurs.

However, if a proposal of this kind proceeds as planned, it should be redesigned to remove its most draconian features. This is the focus of the remainder of this submission.

How the TBT breaks new ground

The TBT proposal clashes with existing tax rules and practice in the following ways:

- The absence of grandfathering of existing assets, which would ensure that the new tax would only apply to assets accumulated in the future.

- The absence of indexation of the TBT for inflation, whereas some (but not all) other caps and thresholds in the superannuation system are indexed.

- The construction of a progressive tax structure applying to super fund earnings, whereas it used to be a flat zero in pension status or 15 per cent in accumulation status.

- Taking the responsibility for calculation and payment of the new tax outside the super system — although there is a precedent for this on the contributions side, with the extra 15 per cent ‘Division 293’ tax on contributions by individuals with taxable incomes above a threshold.

- Taxation of unrealised capital gains, because the new tax applies not to earnings as currently defined and taxed in super funds but to the increase in the value of the total balance whether it stems from real cash earnings and realisation of capital gains or from unrealised or ‘paper’ gains.

- Denial of the one-third discount for capital gains on assets held longer than 12 months, because the definition of earnings does not distinguish between recurrent earnings and capital gains.

- Application of a tax on earnings to defined benefit interests; which in most cases are not based on a fund with earnings, but are taxed in full on the defined benefit pensions as calculated under the rules of the scheme.

Retrospectivity and grandfathering

The new tax targets individuals with large total balances in the superannuation system. However, any balances — no matter how large — have been built from investment earnings and contributions made legitimately under rules that have applied over many years. Contribution limits are now much tighter and may not enable such large balances to accumulate, at least not in real terms. Existing large balances will eventually disappear as a result of benefit withdrawals and the ageing of beneficiaries.

The new tax measure targeting large balances is not retrospective in the sense that it taxes past earnings more heavily, but is retrospective in the sense that it denies, in effect, the validity of past contribution rules that enabled large balances to accumulate. Individuals who made those contributions were entitled to think they were doing so on the basis that the tax arrangements in place at the time would remain — or at least not be made more onerous.

There is a history of grandfathering in such situations; for example, when taxation of superannuation lump sum payouts was increased in 1983. For lump sums received after the implementation date, the new higher rate of tax applied only to the portion saved after that date. Similarly, when capital gains tax was introduced in 1985, assets held at the announcement date and previously free of capital gains tax remained free of the tax for as long as they remained with the same owner.

Applying grandfathering to the new balance-based tax measure would mean exempting all existing balances above the threshold, but disallowing any new contributions.

Any existing balances below the threshold would become subject to the tax if they rose above the threshold as a result of contributions or earnings.

It may be that these grandfathering arrangements would result in little, or no, revenue being raised. However, the measure as announced is unlikely to raise much revenue anyway. Moreover, with grandfathering of balances already above the threshold, the disincentive to the accumulation of balances above the threshold would remain for those who still have the choice because they are still under the threshold.

Level of the total balance threshold and the question of its indexation

Two surprising features of the proposed $3 million TBT for the new tax are that the margin above the Transfer Balance Cap (indexed and now $1.9 million) is relatively small, and that the total balance threshold is not to be indexed. This means the Transfer Balance Cap will eventually reach and overtake the TBT. Under reasonable assumptions, this could happen in 16 years — if not sooner.[3] The government’s proposal is silent on what would happen then.

Would it mean that earnings on the amount of the Transfer Balance Cap above the TBT would be subject to the new 15% tax, thereby going against the intent of the Transfer Balance Cap for that slice of earnings to be tax-free? Or would it be that once the Transfer Balance Cap overtakes the TBT, the Transfer Balance Cap would become the new (and indexed) TBT?

The failure to index the TBT creates a new source of bracket creep in the tax system, with many more individuals becoming subject to the new tax year by year. Creating a new form of bracket creep may be the government’s unstated intention. When announcing the new tax, the government stated that only 0.5 per cent of current super account holders would be affected, but subsequently disclosed Treasury modelling showing that this proportion would rise to 10 per cent in 30 years with no indexation of the threshold.

The number affected is of political significance and affects the amount of additional revenue to be expected in the future. But in another sense, it is beside the point — which is that an ill-conceived tax is still ill-conceived whether it affects 1, 10 or 50 per cent of taxpayers. The government’s emphasis on the small numbers initially affected suits its purpose in claiming that the change is not ‘major’, but sidesteps the reality that the impact on super assets will be ‘major’ for those affected.

The government’s defence is that not every threshold in the super tax system is currently indexed, so there are precedents for not indexing. For example, the $250,000 threshold for applying the Division 293 tax on contributions is not indexed. However, the Transfer Balance Cap and contribution caps are indexed.

While it is true that the application of indexation is uneven in the super tax system and in the tax system more broadly, two wrongs don’t make a right — and the wrong thing with the TBT would be failing to index it.

There is a strong case for indexing the total balance threshold. The simplest way to achieve this would be to express the total balance threshold as a multiple of the Transfer Balance Cap. That multiple should be at least 2 (resulting in a threshold of $3.8 million at the current TBC) and preferably larger.

Progressive replaces flat

For almost 30 years until 2017, super fund earnings had been taxed at a flat 15 per cent on accumulating funds and at zero on funds supporting pension payments. This was simple for funds to administer and was generally accepted, but came under attack when the tax on pensions from super was removed in 2007. As the tax on pensions had an element of progressivity, its removal was seen as diluting the progressivity of the tax system.

The first response was by the Labor government in 2012, introducing the so-called Division 293 tax on contributions — an additional 15 per cent tax on contributions at incomes above $300,000. The second response was by the Coalition government in 2017, which lowered the Division 293 threshold to $250,000 and re-designed the tax on fund earnings by capping the balance on which earnings could be taxed at zero in pension status — the Transfer Balance Cap. In a sense, this was the first step towards a progressive tax on fund earnings, but the rate of 15 per cent did not change.

The current government’s proposed change takes progressivity further by introducing another 15 per cent on top of the existing 15 per cent in limited circumstances. Furthermore, the additional 15 per cent is to be applied to a different measure of earnings from the base 15 per cent. So on an effective basis, it is in fact more than 15 per cent — a point to which we return later.

A case can be made for some progressivity within the super tax system, but the question is the simplest way to achieve it. The progressive contributions tax that already exists is a much simpler way of achieving it than a progressive earnings tax. The Transfer Balance Cap introduced a two-tier tax on earnings from balances supporting pensions, and in doing so greatly complicated what was a very simple system. Super funds were able to cope with that complexity; but the TBT proposal introduces additional complexity that makes it much more difficult to administer the additional tax within the super system.

Taking superannuation tax outside the super system

It is because of this complexity that the TBT proposal for the first time takes the taxation of fund earnings outside the superannuation funds and makes it the responsibility of the individual through the personal income tax system administered by the Australian Taxation Office — although individuals will be given the choice of paying the tax from their own money or instructing their super fund to pay it out of their balance.

The complexity arises because an individual’s aggregate super balance is the key to how the new tax works, and that aggregate may be spread across more than one fund. Funds do not know what their members’ aggregate balances are; and even if they did, they would not have the information needed to apply the new tax.

This is why the government proposal hands the job to the ATO; but the problem with that is that the ATO doesn’t currently collect information on actual realised taxable earnings attributed to individual members within all funds. Hence the move to define ‘earnings’ not as they are currently defined but as the more observable increase in the value of a person’s total super balance each year — information the ATO does collect.

Operators inside the system — funds and the ATO — may be able to devise ways around these problems. But if not, the proposal to use a new concept of ‘earnings’ looks like the tail (administrative convenience) wagging the dog (how earnings should be defined). If the administrative difficulties cannot be overcome, it is better not to go down the path of a progressive earnings tax at all.

Calculation of earnings — taxing unrealised capital gains and denying the discount

In effect, the proposed calculation of earnings makes the new tax a wealth tax — or at least, a tax on the annual increase in this component of an individual’s wealth. There are no other comparable taxes in Australia apart from the states’ land taxes.

Earnings are defined as the increase in an individual’s total superannuation balance with adjustments for contributions and withdrawals. Thus for the first time in the Australian system it includes unrealised capital gains.

Taxing unrealised gains raises questions about how to value assets every year and the compliance burden of doing so. It is not a problem with listed assets but it is with others, particularly real estate. Taxing unrealised gains also creates compliance difficulties in situations where the asset is not generating sufficient cash flow to pay the tax.

It is also important to emphasise that taxation of unrealised gains can result in a much heavier tax burden than if the same dollar gain is not taxed until after realisation. The deferral benefit can be very substantial over long periods. While some tax economists would argue against the principle of deferral, the fact is that it is built into the Australian tax system (and is common in capital gains tax regimes worldwide) and should be applied consistently — not denied from a small segment out of administrative convenience.

Moreover, the capital gains tax discount for assets held for at least 12 months — a one-third discount that applies if the realised gain is taxed within a super fund — is not available to the taxpayer under the government’s proposal.

These issues highlight the desirability of applying the new tax to earnings within super funds as currently defined.

While there are no doubt difficulties, it is not clear that all options for applying the additional tax inside funds have been exhausted. If on closer examination there is no viable way to apply the tax in this way, then the calculation of earnings should be adjusted to recognise the loss of the capital gains discount and the additional burden of taxing unrealised gains. The best way of doing this would be to discount accrual-based earnings by a percentage such as the one-third discount applied to capital gains taxed inside a fund. This would be ‘rough justice’ — as it would not fit any individual’s exact circumstances — but better than no justice at all.

The tax rate

The proposed headline tax is 15% of earnings. However, because of the proposed treatment of capital gains, this represents a much higher effective tax burden than the current 15% tax on earnings inside a fund. It is disingenuous to equate the two.

For this reason, as discussed above, accrual-based earnings should be:

- discounted by one-third; or

- what amounts to the same thing: the headline extra tax rate applied to non-discounted accrual earnings should be set at 10% rather than 15%.

Application to defined benefit interests

The government’s proposal includes the intention to apply “broadly commensurate treatment” to defined benefit superannuation interests as will apply to accumulation interests. Most defined benefit interests are public-sector unfunded pension schemes, which by definition receive no contributions and generate no earnings.

The search for “broadly commensurate treatment” faces two obstacles. One is that in the absence of earnings or a fund it is difficult to impose an extra tax on earnings based on the size of balances in a fund. The other is that pensions from unfunded schemes are currently taxed in the beneficiary’s hands at full marginal rates, subject to a capped tax offset, in recognition of the fact that no tax was paid on contributions or earnings. They are like ‘EET’ schemes, in the jargon of superannuation taxation. A defined benefit pension with a capital valuation of more than $3 million would certainly be well in excess of the cap for the tax offset, and therefore be taxed at a full marginal rate of 47%.

By contrast, pensions from accumulation schemes are untaxed in recognition of the taxes that have been paid on contributions and earnings. They are ‘ttE’ schemes.

There is simply no equivalence and it is illogical and inequitable to suggest that the ‘T’ in the ‘EET’ defined benefit scheme should be increased because one of the much lower ‘ts’ in the ‘ttE’ accumulation scheme is being increased on the grounds that it is (allegedly) too low.

The application to defined benefit schemes seems to be driven by the political sensitivity of a small number of politicians (such as the Prime Minister) who are still members of old parliamentary pension schemes that have long since been closed to new participants. They seem to think that their proposal has to be designed in such a way as to hurt them financially even if this means distorting the design of the new tax in illogical ways. The fact that they will pay the top marginal rate of income tax on their pensions seems not to be relevant.

However, it is understandable that the defined benefit is to be expressed as a capital value and included in the calculation of the total superannuation balance so that the correct tax treatment applies to any superannuation interests that the individual has other than their defined benefit interests. The question is how the capital value of a defined benefit pension is to be calculated each year.

The 16-times formula currently used for Transfer Balance Cap purposes is not fit for purpose because it is intended to be a once-only calculation at the time a pension is commenced. For purposes of the new tax, a more precise actuarial calculation is required to take account of the impact of ageing on the capital value.

Unintended consequences of TBT

Complex tax changes always have unintended consequences, but in this case it is difficult to know what is intended and what is unintended. The public reaction to the announcement of TBT has focused on the prospect of many more super fund members being caught in the net of an unindexed threshold, and the taxation of unrealised capital gains. However, these consequences are so obvious that they must surely have been intended by the government — not that that makes them any more acceptable.

Another consequence will be that those affected by the change will do their best to avoid it by reducing their total super balance below $3 million — or even getting out of super altogether. This may include irrational responses when the alternative is to pay even more tax than the TBT change would impose. But the government would surely be mistaken to think that people would simply shift assets into a fully-taxed form. Rather, there is more likely to be a shift to trusts, negatively geared real estate, assets with returns dominated by capital gains with a 50 per cent discount,[4] up-market principal places of residence with no capital gains tax, and concessionally-taxed insurance bonds. There is also likely to be gifting of super assets to relatives, which will be a form of advance bequests.

Another consequence is that people will incur significant costs in restructuring their affairs to avoid or minimise any impact from the new tax. This is a classic case of the familiar concept of the excess burden of taxation.

The government’s proposal has also been justified as a revenue-raising measure to help reduce the budget deficit, with the Treasury estimating that it will add $2.3 billion a year to revenue once it is fully operational.

However, any claim of significant additional revenue is dubious; as the new tax is likely to be met with strong tax-avoiding behavioural responses as listed above.

Alternative superannuation tax reforms

If the government sees a need to raise more tax revenue from superannuation, there are more sensible options than the TBT.

One would be to take up the 2010 Henry tax review’s recommendation to apply the tax on super fund earnings at a uniform rate on all earnings, with no exemption for earnings on balances supporting pensions. This could be done at 15 per cent or a lower rate such as 10 per cent that may still raise more revenue than the current system. Most importantly, it would be a major simplification, sweeping away all the complexity associated with the transfer balance cap, not to mention avoiding the additional complexity that the TBT will introduce.

Another option would be to align the threshold (currently $250,000) for the Division 293 additional tax on contributions with the threshold for the top marginal rate of personal income tax, which will be $200,000 from 1 July 2024 under the Stage 3 income tax cuts. This means that the tax concession on contributions would be a flat 17 per cent (including Medicare levy) at all taxable income levels above $45,000.

How to make the proposal more sensible

In summary, the government’s proposal should be shelved and reconsidered only in the context of a broader tax reform package. In that context, the alternative reforms outlined above would be simpler and superior to the complex and distorting TBT.

If the government perseveres with the TBT, the proposal needs substantial modification to remove its more draconian features.

Existing total superannuation balances above the threshold should be grandfathered from additional taxation; although new contributions could be disallowed or taxed at a higher rate.

The total balance threshold should be replaced (and effectively indexed) by a balance threshold expressed as a multiple (of at least 2) of the existing, indexed Transfer Balance Cap.

The government should consider any options that would retain the benefit of the one-third discount for longer term capital gains and avoid taxing unrealised capital gains — including reconsidering ways the new tax could be applied inside superannuation funds, just as the existing 15% earnings tax is applied.

If it is not viable to apply the tax inside funds, then a discount factor (such as one-third) should apply to earnings as currently proposed to be calculated. Another way to achieve the same outcome would be to adjust the additional tax rate down from 15% to 10%.

The capital value of defined benefit pensions to be included in the total superannuation balance should be recalculated each year under actuarially-determined rules to recognise the impact of age on capital value.

Endnotes

[1] Andrew Podger, Super tax concessions don’t cost $45 billion a year and won’t cost more than the pension, The Conversation, April 13, 2023.

[2] Professor Jonathan Pincus, Superannuation tax concessions are overestimated, Paper no. 1/2022, Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, Australian National University, February 2022.

[3] This assumes that inflation eases to 3 per cent by 2026 and then remains at the mid-point of the current target band, namely 2.5 per cent.

[4] An individual income tax payer on the top marginal rate of 47 per cent will pay less capital gains tax on discounted gains than the tax on capital gains under the new TBT regime.