Introduction

In Australia, and in education settings across the world, student behaviour and levels of student engagement are significant issues for teachers, school leaders, system administrators and the public. Student behaviour affects community perception, teacher efficacy and wellbeing, and the academic achievement of all students. When students are engaged, they learn more.

This paper uses the current attention on student disruptive behaviour in Australian classrooms to offer policy makers, and educational jurisdiction and school leaders an insight into how to shift the paradigm, policy and practice towards student behaviour in Australian schools.

The solution to disruptive behaviour in Australian classrooms will be achieved if three key ideas gain mainstream recognition. These will be discussed in full later in the paper, but they are:

- Managing student behaviour is about learning. Learning is the result of good management. To maximise learning in the classroom, it is necessary to teach the students how to behave.

- Behaviour needs to be taught explicitly to all students. Instruction in behaviour is central to effective classroom management. The teaching of behaviour needs to be planned, resourced and rehearsed just like any academic content.

- Behaviour as a curriculum needs to be the norm across Australian schools. If behaviour is incorporated in the national curriculum, it would lift standards of behaviour and learning productivity in classrooms. The teaching of behaviour to students would also to help lessen the disadvantage gap in Australian schools.

The problem

Australian classrooms can be loud, unruly places in which students find it difficult to learn. In a 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) study of 15-year-olds, 43% of students surveyed said that they were in classrooms that were noisy and disruptive. This is well above the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average of 33%, and places Australia 69th of 76 countries on the ‘disciplinary climate index’, which means Australian schools are among the least orderly in the world. These statistics are telling, as orderly classrooms are a pre-condition for student learning.

In response to the increased awareness of the disruption in classrooms, the federal government, through its Senate Education and Employment Reference Committee, has launched an inquiry into “the issue of increasing disruption in Australian school classrooms”. The inquiry also will examine what universities are doing to prepare teachers to deal with disruptive behaviour. Meanwhile, the government has set up the Teacher Education Expert Panel (the Panel) to give advice on key practices every teacher should learn in Initial Teacher Education (ITE) to prepare them for disruptive student behaviour.

The recommendations in the Panel’s final report ‘Strong Beginnings: Report of the Teacher Education Expert Panel’ are designed to strengthen ITE in Australia. The Panel identified the core content for ITE programmes that met the Graduate Teacher Standards and had the greatest impact on student learning. The other core content area was ‘Classroom Management’. The report highlighted the need for graduates to know how to establish a classroom that enabled student learning. The Panel commented that classrooms that enabled student learning were characterised by clear expectations, supported by routines and rules to ensure students were safe and engaged in learning. In these engaged classrooms, the teacher models and gives feedback on expected behaviour rather than reacting to off-task behaviour.

The OECD Policy Perspectives Report (2023) notes that there is a “current need in Australian schools to strengthen learning environments to become fully conducive to learning”. There is still work to do, as identified in the behaviour climate index rating with the added evidence that 37% of lower secondary Principals report that intimidation and bullying among students occurs at least weekly (TALIS, 2018). It is not just students that do not feel safe in classrooms or in school. In the same report, 28% of teachers identified maintaining classroom discipline as a stressor, and 13% reported being intimidated or verbally abused by students. The TALIS (2018) data is supported in the ‘Perceptions of Teachers and Teaching’ study by Heffernan (2019), where 19% of teachers reported that they did not feel safe in classrooms or at school.

What is the nature of disruptive behaviour in Australian schools?

Research over the past 40 years is clear as to what distracts teachers from teaching. The behaviours that teachers find difficult to manage are often minor but high frequency and low-level (Department of Education and Science, 1989; Johnson, Oswald, & Adey, 1993; Beaman & Wheldall, 1997; Angus, et al, 2009; Beaman, R., Wheldall, K., & Kemp, C., 2010; Sullivan et al, 2014). Low-level behaviours identified in the research involving Australian teachers were commonplace, such as talking out of turn, and avoiding work. The frequency and repetitive nature of these behaviours contributes to the disruption in the classroom for student learning and teacher instruction time and stress (Oswald, &Adey, 1993; Sullivan et al, 2014).

The Grattan Report (Goss and Sonnemann, 2017) reflected this research on low-level behaviour: “the main problem is not aggressive or anti-social behaviour[,] as more prevalent and stressful for teachers are minor disruption[s]” (p.3). The Grattan report based these statements on the Pipeline Project (on which the author was a researcher), a significant longitudinal study conducted in Western Australia that resulted in a report titled ‘Trajectories of Classroom Behaviour and Academic Progress: A Study of Engagement with Learning’ (Angus, McDonald, Ormond, Rybarczyk, Taylor and Winterton, 2009). The project sought to describe the kinds of student behaviour that were impeding students’ academic progress. These were referred to as ‘unproductive behaviours’.

The research paints a consistent picture of widespread low-level disengagement and disruption. It found that 40% of students displayed unproductive behaviours regularly in any given year. In this group of unproductive students, more than half were in a ‘compliant disengaged’ group, described by their teachers as uninterested in their schoolwork, unprepared for lessons, and quick to give up tasks they found difficult or boring. The most common unproductive behaviour identified by teachers was inattentiveness.

Disengaged students have an effect on academic achievement in classrooms across Australia. The Pipeline Project study tracked students over four years, and found that students who were unproductive (40%) were, on average, one to two years behind peers in literacy and numeracy (McDonald, 2019, p.78). Interestingly, the study highlighted that these quiet, yet disengaged, students did just as poorly as the students whom teachers identified as disruptive. John Hattie (2012), referring to the Pipeline Project study, commented that ‘these ambivalent [unproductive] students should be the focus of teachers attention — and are perhaps the easiest to win back’ (p.112). Hattie’s point highlights the reality that creating calm, orderly and inclusive classrooms in Australian schools is possible. There are evidence-based practices that teachers can use in their classrooms to effectively and efficiently create environments where all students learn.

Solutions

Developing calm and orderly classrooms in Australian schools that engage students in learning requires three ideas identified in the Introduction to be understood and implemented at the classroom, school, and system level:

- Managing student behaviour is about learning.

- Behaviour needs to be taught explicitly to all students

- Behaviour as a curriculum needs to be the norm across Australian schools

Managing student behaviour is about learning

Student learning does not happen by chance. It is a result of planned and intentional teacher actions. The actions a teacher takes to develop a calm, orderly and inclusive learning environment begin outside the classroom in a well-thought-out plan incorporating evidence-based strategies. The plan needs to include strategies to deal with student inattention and misbehaviour. This plan to set up the conditions for learning, prevent misbehaviour and to be able to manage student behaviour is called classroom management. The outcome of effective classroom management is student learning.

Classroom management involves “teacher actions and instructional techniques to create a learning environment that facilitates and supports active engagement in both academic and social emotional learning” (McDonald, 2019, p.19). This definition has two parts or processes. The first is purposeful teacher actions to establish the learning environment so all students can engage in learning, and the second is to help students grow socially and morally to be able to live with others. All rules from kindergarten to Year 12 are about being a good citizen in a community or school.

The inclusion of ‘social and emotional learning’ in the definition of classroom management is to acknowledge that ‘engagement’ in learning is multifaceted and involves factors of student disposition as well as the instructional skill of the teacher. Reeve (2004), who built upon the research of Fredricks, Blumenfeld and Paris (2004) and Furrer and Skinner (2003) outlined in detail the student element of engagement. Reeve described engagement as consisting of a student’s behavioural intensity, emotional quality, and personal investment in their involvement during a lesson. In Reeve’s (2004) model, engagement is expressed in a student showing attention, effort and persistence.

It is deliberate teacher actions that encourage both student participation and the development of behavioural skills that result in students learning. Engagement is a product of students’ attention, effort, emotions, cognitive investment and participation, and teacher actions that encourage participation and the development of behavioural competence. Through a student engagement lens, deliberate teacher actions in establishing norms of behaviour, routines and processes in the classroom, as well as rules, are seen as crucial and as a precondition to student engagement and learning.

Student learning is an adult responsibility. How well teachers manage their classrooms will determine how well their students learn. Wong (2018) cites research on elementary, middle and high schools by Emmer and Evertson (2012), who stated that: “classroom management skills are of primary importance in determining teaching success; The most significant factor governing student learning is classroom management(p.93)”. It is easy to see why the Expert Panel identified ITE students being skilled in classroom management as crucial.

A well organised classroom is consistent. A consistent classroom is inclusive. Consistency is an important element to establish with students from day one. Knowing how the class will work and what is expected of them increases anticipation rather than anxiety about the year ahead. Students with anxiety or worries about how they will fit in or belong in a class, or a school, are reassured from day one on how the class will be structured and organised. A consistent classroom is predictable, reliable and stable because there are clear norms of behaviour, routines to follow, and rules. Coupled with this behavioural consistency is the consistency of instruction, with clear learning objectives and guidance from the teacher.

A calm, consistent and predictable classroom provides a safe learning environment for students who have been exposed to adverse childhood experience or trauma. The Berry Street submission to the Senate Inquiry into the ”Issue of increasing disruption in Australian school classrooms” supports the assertion that teacher-led classrooms that are predictable and consistent are helpful to vulnerable students. In their submission, when referring to the elements of an effective approach to student behaviour, they highlight ”consistent expectations and predictable consequences — providing clear expectations and consistently reminding students of them creates a sense of safety” (p.6). Importantly, the submission tackles the misconception that working with students who have experienced trauma does not mean ‘excusing’ behaviour or allowing students to act inappropriately. In fact, in their work, Berry Street states that “students presenting the most dysregulated behaviour are the ones who thrive the most in caring yet firm environments”.

A teacher focus on learning when dealing with students’ behaviour will necessitate reconceptualising how teachers speak about student behaviour. If learning is the focus, then disruptive student behaviour is seen as any behaviour or action that impedes academic engagement or attainment (Goss, et al 2017). The focus on learning shifts the conversation with students to how their behaviour is interrupting their learning, the learning of others, and the instruction of the teacher. This keeps the focus on learning and avoids the distraction of teachers attributing behaviour to unmet needs, medical conditions or other causes. This shift in language helps students to take responsibility for their behaviour and learning.

It is important to remember that classroom management is about practices and routines a teacher uses to create and maintain a classroom environment in which instruction and learning can take place efficiently. Learning is the result of good management. Teachers who are skilled in classroom management ensure their students are engaged and create a productive working environment. The classroom is about learning. To maximise learning in the classroom, it is necessary to teach the students how to behave.

Behaviour needs to be taught explicitly to all students

Schools need to teach students how to behave. Just as cognitive abilities vary, so too do students come to school with varying levels of ability and skill to behave in classrooms. Children will not spontaneously behave because they are in a school or classroom. Every classroom in Australia is filled with students from different backgrounds with different values and beliefs about what good behaviour is. To help students succeed in learning in a class full of individuals, the teacher needs to teach them how to behave in that class.

As with any new skill or concept, behaviour needs to be taught explicitly. The teaching of behaviour needs the same planning, rigour and skill as the teaching of any subject content. A behaviour curriculum needs to be developed and resourced in the same way as subject curricula. No classroom teacher from kindergarten to Year 12 assumes students’ knowledge and ability or teaches without recognising the academic level of the class. Regardless of whether a student has been at school for one year or 11, any new class of students with a new teacher is a whole new classroom ecosystem, and thus the students need to know what good behaviour is in this new class.

Instruction in behaviour is central to effective classroom management. The teaching of behaviour needs to be planned, resourced and rehearsed just like any academic content. Planning involves considering what behaviour to teach. The teacher needs to know exactly how he or she wants the students to behave in the many different contexts of the class. This behaviour curriculum needs to be sequenced and age- or ability-appropriate, and taught using the same instructional principles used in subject areas. This teaching will involve understanding students’ current knowledge, checking for understanding, practising, repeating instructions, and continuously reviewing the students’ understanding. At times, a repeat lesson may be necessary and, as in content areas, some students may need a lot more attention before they master the behaviour.

What to teach

The need to teach students how to behave is not a newly recognised idea. Research from the 1970s and 1980s began to examine the classroom behaviour of teachers and to identify the strategies that effective teachers use in classroom management. Research on what is essential in classroom management began with Jacob Kounin in 1970. Kounin observed 49 First and Second Grade classes, and selected students, whose behaviour was recorded at 12-second intervals. From this research, Kounin surmised that effective classroom management was based on the behaviour of the teacher and not the behaviour of students.

Anderson, Evertson and Brophy (1979) built on this work in their Third Grade study, which identified clusters of behaviours that effective teachers displayed, which were:

■ conveying purposefulness

■ teaching students appropriate conduct

■ maintaining student attention (Brophy cited in Evertson & Weinstein, 2006, p. 30)

These effective classroom managers established (and taught) clear and high expectations for student behaviour. In their study of Junior High Schools, Evertson and Emmer (1982) found similar teacher behaviours. Brophy (cited in Evertson & Weinstein, 2006, pp. 31–2) notes that effective teachers had the following characteristics:

■ instructing students in rules and procedures

■ monitoring student compliance with rules

■ communicating information

■ organising instruction.

Three international reports are significant here in identifying evidence-based strategies for establishing calm and orderly classrooms: a comprehensive summary by Simonsen, Fairbanks, Briesch, Myers and Sugai (2008); another by Oliver, Webb, Wehby and Reschly (2011); and a third by the Institute for Education Sciences (2008), titled ‘Reducing Behaviour Problems in the Elementary Classroom’. These provide an overview of more than 150 studies conducted over six decades. Together, these studies provide evidence that highlights common strategies for managing a classroom effectively. These strategies are reflected in National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) research into classroom management that identified the ‘big five’: Rules (stated high expectations of behaviour); Routines (teach routines and procedures); Praise (reinforce positive behaviour); Misbehaviour (strategies to respond to misbehaviour); Engagement (quality instruction).

Contemporary reports or guidelines (AITSL, 2021; AERO, 2021; E4L, 2023) on student behaviour repeat what earlier research has said on evidence-based practices involved in classroom management. The “Tried and Tested” resource ‘Managing the classroom to maximise learning’ from the Australian Education Research Organisation “synthesised the most rigorous and relevant evidence-based practices from meta-analyses, systematic reviews and literature reviews” and highlighted a number of strategies. The four top strategies were:

- Establish a system of rules and routines from day one

- Explicitly teach and model appropriate behaviour

- Hold all students to high standards, and

- Actively engage students in their learning.

The organisation Evidence for Learning (E4L) aims to provide easily accessible, evidence-based material to teachers and school leaders. In 2023, E4L released a guidance report titled ‘Evidence for Learning’, based on original content from ‘Improving Behaviour in Schools’ (Education Endowment Fund), which made modifications for an Australian context through a panel of research and practitioner experts. The guidance report again reaffirms earlier classroom management research and has six recommendations that fall into three categories: proactive strategies, responsive strategies, and implementation. The proactive strategies align almost exactly with AERO’s, and reinforce the need for teachers to “teach learning behaviours” to students and to “use strategies and routines to support expected behaviour”. Included in this set of recommended strategies and routines to support behaviour is specific behaviour-related praise, as also identified in the American NCTQ’s ‘big five’.

From the early pioneers of classroom management research to present day reports, ‘what to teach’ is clear. To increase engagement in Australian classrooms, teachers need to be skilled at teaching students how to behave. Classrooms need to have teachers explicitly teaching a behaviour curriculum that clearly outlines high expectations (norms of behaviour), routines, procedures and rules.

Students also want teachers who can control the class. Student feedback on what makes an effective teacher includes an ability to manage the classroom so that learning can occur. In early research on effective teachers, Judith Kleinfeld (1975) coined the term ‘warm demanders’. Kleinfeld found that the most effective teachers (at least in the predominantly Native Alaskan schools she studied) were those who combined high expectations with warmth, empathy, and a strong belief in their students’ abilities. Kleinfeld noted that these ‘warm demanders’ were able to create a positive supportive classroom environment that fostered both academic and personal growth in their students.

Australian writer Christine Edward-Groves (2012) in her article ‘Strategies for engaging young adolescents: Transforming the role of teacher as warm demander’ argues that the warm demander approach involves having high expectations of students and building positive relationships with them while holding them accountable for their learning.

The warm demanders approach is sensitive in culturally diverse classrooms and with Indigenous students. Zaretta Hammond (2015) uses the concept of warm demanders in her book Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain. Warm demanders, Hammond believes, are teachers who are both supportive and challenging of their students. They create a classroom environment that is both nurturing and academically rigorous. Importantly, being a warm demander is not about demanding obedience or no-nonsense firmness, but an insistence on excellence and academic effort, irrespective of background.

Hammond states that warm demanders are essential in culturally responsive teaching because they recognise and value their students’ cultural background while holding high expectations for academic achievement. Warm demander teachers can build strong relationships with their students and create a sense of belonging in the classroom while pushing their students to reach their full potential.

Research by Giota and Koustourakis (2015) supports Hammond’s work. They found that the majority of students they surveyed preferred a teacher-centred approach to learning where the teacher was seen as the primary source of knowledge and authority in the classroom. Similarly, a study by Ormond and Martin (2013) found that students perceived teacher control as a positive factor that provided structure and discipline in the classroom and helped to ensure that learning goals were achieved.

Make it normal to behave

All schools and classrooms have a culture that reflects what is important or matters most to them. Classroom culture refers to the shared beliefs, values, attitudes and behaviours that help to shape the learning environment. Culture is the collective personality of the group. Every class has its own personality, as it is made up of a collection of different students and a teacher. Each of these classroom groups or cultures will have norms of acceptable behaviour to which each student needs to conform . It is important for the teacher to first be clear as to the culture they want, and second the norms that characterise this class. Once the values that underpin the culture are known (e.g., respect, community, care, kindness), these have to be taught to the students.

Defining the values that underpin a classroom culture is not to dismiss or ignore students’ home culture. Being culturally responsive to students means acknowledging and acting respectfully towards their beliefs and values. However, it is also about the students’ understanding that the classroom has its own culture, values and beliefs that should be held and reflected in their behaviour in the classroom. These norms of behaviour that underpin the class culture are intended to support the students to learn and behave responsibly.

Developing a positive classroom culture where students appreciate the need for good behaviour as a requirement for learning will help students feel a sense of belonging and safety with the group and the teacher. Developing a cohesive culture is time-consuming and difficult. Classes of all ages are made up of students pre-programmed with various cultures, beliefs and values, and individual student beliefs and values underpin behaviour in class. If a student comes from a home environment that does not value learning or teacher authority, then those beliefs will surface when the student is asked to complete work, hand in homework or follow teacher instructions.

In creating calm and orderly classrooms, teachers need to teach students how to behave and that it is normal to do so. Tom Bennett in his 2012 book Running the Room has a great maxim for teachers to refer to in developing norms, routines and rules. His “golden rule of behaviour: make it easy for them to behave and hard for them not to” (p.127). Making it easy for students to behave means removing barriers or obstacles to them behaving correctly. One way to help students to get clarity on the behaviour required to learn is to make the norms, routines and rules transparent and to teach them explicitly.

Norms play a critical role in developing a positive classroom culture. Norms are the standards of behaviour and expectations that frame what happens in the classroom. Norms are the actions that are seen, heard and felt in the classroom. When norms are clear and consistently enforced, they create a sense of safety and predictability in the classroom. Students know what is expected of them, from how to enter the classroom to the end of the lesson or activity. This level of mutual predictability builds trust and a sense of belonging, both of which are important foundations for positive teacher–student relationships.

Teachers need to clearly define, explicitly teach, and model what normal behaviour is in the classroom, and the value that underpins or justifies that behaviour. Whatever the values or desired behaviours selected for the class, these need to have been planned and stress-tested by the teacher before the first class. If the value of ‘respect’ is to become a norm, it needs to be taught to the students. Students need to experience respect in the classroom from the teacher and other students. This will mean setting time aside from day one of class to discuss the value, what it means, and why it is important in this class. This value of respect is one of the high expectations the teacher has for the students in this class, as it is expected that they will be respectful in their interactions with the teacher and students. Just like subject content, skills or concepts, respect needs to be taught and taught often. Reteach it as often as necessary if students are not acting respectfully, and reinforce or affirm their behaviour when it is respectful.

Developing lifetime habits

Routines play an important role in building and maintaining classroom culture. Routines reinforce norms and values in the classroom. When routines are aligned with the desired culture, they promote and reinforce the values that underpin behaviour. The power yet simplicity of routines is that they help to create consistency of behaviour, which promotes a sense of trust and reliability, reducing any stress or uncertainty a student has as to how to behave.

Routines are a sequence or chain of actions that begin from a cue from the teacher that is executed with minimal cognitive effort or conscious control. Routines are about efficiency and habit formation. Routines help students perform tasks—such as entering the class, answering a question, moving around the class or school — with less cognitive effort. Routines help students (and teachers) establish positive habits by consistently performing certain behaviours or actions until they become automatic. This automaticity is the end goal of routines or processes in the classroom, reducing the need to stop and think, thus maximising instruction and learning time.

Routines act as recipes, with steps to follow to achieve a goal. The sequence is important, as it makes the learning of the routine easier; the steps can be taught sequentially and practised in smaller parts until the students have mastered the full sequence.

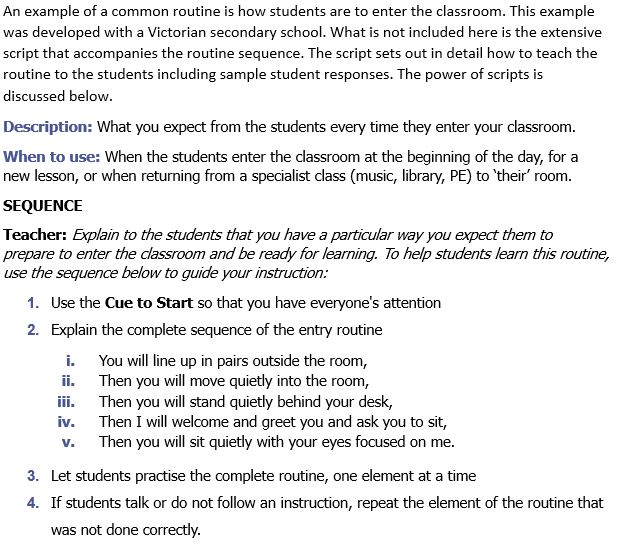

TEXT BOX: Classroom Entry Routine

Routines will differ according to the age and makeup of the students in the school, and the school’s culture. What is important is that all students know the purpose of the routine, what the routine sequence is, and that it is used consistently and often. Although routines will vary, some are obvious yet crucial to engaging students in learning and providing a calm, safe and inclusive learning environment. These include routines for answering a question, asking a question, speaking and listening, moving around the class and school, focussing on the teacher, transitioning from one activity to another in the classroom, and entering and exiting the class.

Charles Duhigg (2012), in his book The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business, defines a habit as a “choice that we deliberately make at some point, and then stop thinking about but continue doing, often every day”. He suggests that habits are formed through a three-step process: cue, routine, and reward. Duhigg’s work supports the teaching of routines explicitly if teachers are to help students develop independence and to have greater self-control. The need for teachers to have a consistent and persistent approach to student routines and habit formation is outlined in Lally’s (2010) research analysis, which found that it took an average of 66 days for a behaviour to become a habit. Through a well-thought-out and consistent approach to a behaviour curriculum, schools can have a powerful influence on children and young people’s behaviour and decision making.

Rules support consistency and fairness for all. In the classroom management research, rules are seen to actively contribute to developing calm and orderly classrooms. Rules are necessary and help to provide a safe and orderly learning environment for all students. Rules support the expectations set by the teacher and promote consistency and fairness in the classroom and school community. When rules are explained and justified as helping to develop good behaviour, they assist in the development of respect, self-discipline and responsibility. In establishing a classroom characterised by the value of respect, ‘no calling out’ or ‘one person speaks at a time’ is really a rule about listening and treating each other and others’ opinions with respect.

For students, rules, like norms, need to be seen, heard and experienced, not just told. Rules also need to be taught, and the rationale behind each rule explained. Students need to understand why the rule exists and how it is meant to help them contribute to a safe, calm and orderly learning environment. Rules, like norms and routines, need to be reinforced consistently, and the teacher needs to live by these rules and set high expectations that the students will do the same.

When the students experience rules as important, it helps to establish a culture of accountability that reinforces that learning is important in that class. Rules reinforce the value that is important to the class culture. It is easier to understand the rules that apply in planes when passengers understand that they support the airlines value of ‘safety’. Airlines value of safety drives the procedures of how passengers enter and exit the plane as well as the rules in the plane of wearing a seatbelt, window shade up and tray table stored.

From the early days of classroom management research (Weinstein, Evertson, Kounin) to recent systematic analysis and reports (AITSL, AERO, E4L), the need for teachers to have high expectations of students has been seen as paramount. The challenge with high expectations is that most teachers would say they have them, but the level of expectations can vary from teacher to teacher. What one teacher believes is a high expectation — allowing students to hand in homework up to three days late, for instance — would be seen as a low expectation by another teacher. These teachers may work at the same school and teach the same students. Research by Rhona Weinstein (1987) found that students as early as Year 1 can accurately and consistently describe the expectations a teacher has of them by their facial expression, body language and posture. Students know which teachers have high expectations and which do not.

High expectations are achieved when the values that underpin classroom norms, routines and rules are taught, modelled and followed up consistently. Students will learn the level of expectation (low to high) if they are reminded of the standard when they fall below it or do not follow it. Students learn that, in this class, this is the expectation, and that it is aimed at student learning and personal responsibility. This authenticity of the teacher modelling and following up on expected behaviour demonstrates what they will and will not stand for in their classroom. Warm demanders, as identified by Judith Kleinfeld (1975)are authentic in developing relationships with students while demanding high expectations.

How to teach behaviour

Students need to be taught how to behave in the same way they need to be taught phonics, times tables or any foundational skill. Telling students to behave, giving them a copy of rules and asking them to stick it into their workbooks will not achieve the desired behaviour. Students need to be taught the norms, routines, and rules which model the high expectations in the class. Students cannot be left to intuit the behaviour expectations or to co-construct them in collaboration with other students. Behaviour needs to be taught in a way that matches how humans learn: explicitly.

Explicit instruction helps students to learn by providing a clear and structured approach. It involves breaking down complex skills and concepts into smaller, more manageable parts, and teaching these parts in a systematic and explicit way. This approach allows students to build a strong foundation of knowledge and skills, and then gradually build upon this foundation as they progress through their learning.

Teachers can use the same evidence-based instructional strategies (e.g., Rosenshine’s (2012) Principles of Instruction) they use for their subject content in teaching students how to behave. The importance of teaching behaviour explicitly is that it incorporates students practising the skill. Kirschner, Sweller and Clark (2006) highlight the need for practice and feedback for learning. Take the ‘entering the classroom’ sequence set out above. When taught explicitly, students are given the opportunity to practise the sequence (lining up outside, walking into the room to their desk, standing behind their desk, greeting the teacher, and quietly sitting down), and are given immediate feedback and correction on how they perform the various steps. If students are not completing a step correctly, it is easy to practise that step until students have mastered it.

It would be a mistake to assume that all teachers know how to teach behaviour. John Sweller laid the foundations for the development and refinement of his Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) and its implications in his seminal article ‘Cognitive Load Theory during problem solving: Effects on learning’ in the journal Cognitive Science in 1988. One of the emerging understandings in CLT is the distinction between experts and novices in terms of their prior knowledge, schema development, and cognitive processing abilities. It is possible to assume that, in teaching students how to behave, there will be a continuum among teachers from novice to expert. This has implications for a behaviour curriculum. As with the current Australian Curriculum, it would be foolish to think that because we have a curriculum all teachers are effectively implementing it and achieving a high level of student competence. If a behaviour curriculum is to be effective in reducing disruption in Australian classrooms, it will need to be clearly defined and structured with materials that enable a novice to teach behaviour to students with fidelity and evidence of its impact.

Outcomes of teaching behaviour at Michaela Community School, UK

There are no randomised control trials looking into the effectiveness of large schools’ implementation of teaching of behaviour to students. There is research and commentary on the implementation of whole school approaches to student behaviour (Bradshaw, Waasdorp, Leaf, 2015) as well as research on programmes for student behaviour (Cook, Larson, Daikos, Slemrod, Holland, Thayer, Renshaw (2018). In Australia, there are anecdotal insights from individual classrooms or schools on the benefits to the level of calmness or engagement of students, but there is no documented systematic evaluation or research on the impacts on students learning linked to the explicit teaching of behaviour. However, outcomes documented at Michaela Community School in the UK are suggestive.

Katharine Birbalsingh is the founder and head teacher of Michaela Community School, a free school in London. She has spoken publicly about the achievements of her students, particularly their academic performance. Citing exam results, Birbalsingh argues that the school’s approach to education, which emphasises high academic standards, as well as the teaching of behaviour, routines and rules, has helped students from a variety of backgrounds achieve success. For example, in 2021, 97% of Michaela Community School students achieved a grade of 4 or better in English and Maths GCSEs, which is higher than the national average.

Birbalsingh has also noted that a significant proportion of the school’s students come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and that a large proportion of students have gone on to attend top universities or pursue successful careers.

Michaela Community School — and the documentary film highlighting its approach to behaviour and teaching practices — is one example of how a teacher-led classroom that teaches behaviour can improve student engagement and achievement.

Behaviour as a curriculum across Australian schools

Across Australia, individual teachers give instruction to students on how to behave in classrooms and schools, but there is no state or national behaviour curriculum. The challenge is to make explicit teaching of behaviour the norm in Australian schools. There are parallels to the growing adoption of the Science of Learning and the teaching of phonics; there is still resistance to the evidence supporting the science of reading, but the teaching of phonics is widely accepted, enshrined in policy, practice and screening assessments across states and territories.

What is a behaviour curriculum?

A behaviour curriculum defines the expected behaviours in a school. The behaviour curriculum outlines the values of the school and the intended behaviour culture of the school. It clearly outlines the way that these behaviours will be taught and maintained throughout the school. As part of the behaviour curriculum the routines and rules that help to develop the behaviour culture are described. The Department for Education in the UK have outlined their expectations for schools to have a behaviour curriculum and what is required in a school behaviour curriculum in their ‘Behaviour in Schools: Advice for Headteachers and school staff (2022). The advice states:

“A behaviour curriculum defines the expected behaviours in school, rather than only a list of prohibited behaviours. It is centred on what successful behaviour looks like and defines it clearly for all parties. For example, ‘pupils are expected to line up quietly outside a classroom. A behaviour curriculum does not need to be exhaustive, but represent the key habits and routines required in the school” (para 19).

The advice also highlights the importance of routines in establishing a positive behaviour culture and that routines need to be easily understood by all students;

“Routines should be used to teach and reinforce the behaviours expected of all pupils. Repeated practices promote the values of the school, positive behavioural norms, and certainty on the consequences of unacceptable behaviour. Any aspect of behaviour expected from pupils should be made into a commonly understood routine, for example, entering class or clearing tables at lunchtime. These routines should be simple for everyone to understand and follow” (para 20).

If Australia was to incorporate behaviour into its national curriculum, it would be revolutionary in the potential effect it might have on student behaviour and learning productivity in classrooms around the continent. The teaching of behaviour to students will help lessen the disadvantage gap in Australian schools. Students who have the skills and ability to listen to the teacher, ask questions appropriately, follow instructions, sit on a mat or at a desk will have the opportunity to learn and keep building on their knowledge as a foundation for future learning. Students who do not have such capabilities will miss key building blocks of learning, have less knowledge, and will potentially fall further and further behind.

The development of a behaviour curriculum and the normalising of the teaching of behaviour has the potential to reduce the Matthew Effect — where the rich get richer and the poorer get poorer when it comes to educational outcomes — in Australian schools. This is a challenge that policy makers and education system and jurisdictional leaders need to address through targeted interventions and supports. These are things that a clearly defined and well-resourced behaviour curriculum can deliver, along with opportunities for equity it could bring to all Australian children. A behaviour curriculum that gives all students the opportunity to learn in every classroom across Australia is a moral imperative.

Including the teaching of behaviour in the Australian Curriculum would give it a greater sense of legitimacy to a broader range of teachers. There is a natural place for a behaviour curriculum in the Australian Curriculum. Its current structure comprises the Key Learning Areas, General Capabilities and Cross Curricular Priorities. The Australian Curriculum and Reporting Authority (ACARA), which oversees the Australian Curriculum, states that the seven General Capabilities “equip students to be lifelong learners and […] to operate with confidence in a complex, information-rich, globalised world” (ACARA, 2023)(Structure: The Australian Curriculum (Version 8.4)). In the list of the seven General Capabilities, behaviour is not mentioned, yet knowing appropriate behaviour and being able to apply this in a range of complex, information-rich settings would seem to be an advantage to those students who do not have the capability of behaving appropriately. It would not take much to include an eighth General Capability on Behaviour.

Teaching students how to behave through clearly defined social values, norms of behaviour, routines that build classroom and school culture, as well as rules has more chance of being adopted thanks to the gradual awakening in the Australian education community to the Science of Reading and the Science of Learning. Education Systems are promoting instructional programmes based on the evidence of how humans learn, resources to understand CLT and its implications for teaching (CESE) and a movement of likeminded Science of Learning teachers and leaders is slowly growing across Australia.

The teaching of routines and rules is best supported through the use of scripted resources. Scripts reduce the cognitive burden on teachers as to ‘what to teach’ and ease the anxiety of how to teach it. Scripted resources clearly spell out the sequences in routines and provide ‘speaking notes’ for the teacher to say when teaching the students. Scripts are valuable tools for teachers; they promote consistency, clarity, efficiency, adaptability, and are a source of professional learning for teachers as they build knowledge on routines and how best to teach them to students.

In mathematics teacher professional learning, scripts of effective teaching strategies were seen as helpful for teachers in developing the skills and knowledge of those strategies (Davis & Simmt, 2006). Similarly, Linn and Eylon (2011) discuss, in their book, that providing students with scripts of effective science practices can help them develop a deeper understanding of science concepts and processes. Providing students with the scripts of routines and desired behaviour would help provide a visual prompt and scaffold of what is to be learnt. The scripts can also serve as a revision source for when the teacher quizzes students’ understanding of a routine, sequence, or rationale behind a rule.

Codification of professional knowledge in scripts ensures fidelity to the intended behavioural outcome. Codifying a process or sequence on how to teach behaviour makes the tacit knowledge of expert teachers, who create calm and orderly classrooms, explicit, and facilitates learning and knowledge sharing across the profession. Codified scripts provide teachers with clear and structured guidelines for the teaching of behaviour. The use of scripts with teachers in a school helps to make the teaching of behaviour a school activity, and has the potential to promote effective collaboration and problem solving of specific behaviours in the school (Kollar, Fischer, and Hesse, 2006).

In research on the use of scripts in teacher professional learning, the cost of implementation being prohibitive was not commented on. Determining the cost-effectiveness of any educational intervention requires consideration of both the costs and benefits of the program, and an evaluation of its sustainability over time.

Teaching behaviour is cost-effective

The teaching of behaviour as a curriculum is not labour-intensive, and nor does it rely on international or expensive facilitation. As with the implementation of a subject curriculum, there are people who are knowledgeable and skilled at teacher professional learning. The same is true for behaviour as a curriculum; there are people who are more knowledgeable and skilled at teaching teachers why teaching of behaviour is important, how to teach a behaviour curriculum, and what the expected outcomes are from this intervention. Much of this expertise already exists in schools. The challenge will be at the school level as to what culture, norms, routines and rules the school wants the students to experience. The challenge for school leadership is to shift prevailing barriers based on ideology and teachers’ novice status when it comes to understanding the science of learning around Cognitive Load Theory and how students ‘learn’ behaviour. Enabling students to learn in calm, orderly classrooms, and teachers to teach as effectively as they can, is worth the effort and perseverance.

The need to teach behaviour in universities

The Teacher Education Expert Panel Report has given the Australian Government the evidence and background to mandate the teaching of behaviour in Australian universities Schools of Education (SoE) — a move that would enable SoEs to increase the quality and competence level of graduates. The teaching of behaviour needs to align with the Science of Learning where new skills and concepts are taught explicitly. Initial Teacher Education courses need to include the teaching of behaviour and to enable the students to understand what a behaviour curriculum is and to develop curriculum resources of the teaching of behaviour as they do in subject areas.

The teaching of behaviour in Schools of Education must include the skills teachers use to establish and maintain a calm and orderly learning environment. Effective teachers work very hard at using these skills through a lesson to maintain high levels of student engagement. These skills include proximity, voice, pause, scan, the look, with-it-ness, politeness, acknowledgement, praise and gesture. Successful teaching of routines, norms and rules will be dependent on how effective the teacher is at executing these skills to enable students to learn and practise the routine. Graduates who have learned these skills and had opportunity to practice this while out on practicum placement will have greater chance to create calm and orderly classrooms in their first school.

The teaching of these skills supports the work of Kevin and Robyn Wheldall, who developed MultiLit’s Positive Teaching and Learning Initiative to assist teachers provide positive learning environments. The five components in the Wheldall Positive Teaching model include:

- Identify conditions in the classroom that impact behaviour and change to forge the optimum learning environment.

- Establish agreed specific classroom rules for behaviour.

- Praise the positive, instead of a focus on reprimanding disruptive behaviours.

- Reprimand effectively. Reprimands are most effective when they are used infrequently in a predominantly positive climate.

- Be consistent. Students respond positively to the implementation of school-wide expectations, which are seen as ‘fair’.

It would be an asset for ITE students to be skilled in the use of praise to help promote a positive learning environment, as identified in the Positive Teaching model. The research found that for “praise to be effective, it must be pinpointed, sincere and varied”. The other components support the need to establish clear expectations and routines and ensure that expectations are followed up with ‘effective reprimands’.

The challenge for universities will be to shift their current staffing capabilities to include practitioners who have the capacity and knowledge to demonstrate the skills needed for effective behaviour management in the classroom. It would be a stretch to think that in response to The Teacher Education Expert Panel Report that universities could swiftly staff the teaching of behaviour with skilled practitioners from within existing staff. The need to teach behaviour in SoEs that includes norms, routines and rules raises the issue of where should teacher education be situated and are SoEs best placed for contemporary teaching. If universities are slow to move to the teaching of behaviour then the preparation of teachers should be outsourced to evidence-based providers as is the case in the UK.

The realignment of university courses to the teaching of behaviour that includes teacher skills provides an opportunity for the AITSL Teacher Standards to include specifics on behaviour teaching. At present behaviour management is inadequately included in ‘Standard 4: Create and maintain supportive and safe learning environments’. The standard is devoid of what a teacher needs to do to create, let alone maintain, a safe learning environment. There are some broad statements of what graduates should be able to demonstrate, however they are not sufficient in detail about the specifics on what a safe classroom looks like for them to demonstrate.

This is in contrast to the specific detail outlined in the UK’s Department for Education’s Early Career Framework (2019). This framework was implemented with a well stepped out two-year professional learning plan for graduates. The framework has been designed to support early career teachers in five core areas with one being ‘behaviour management’ which includes setting high expectations and managing behaviour effectively. The sub strands to the framework talk about ‘explicitly teaching routines’, ‘practising routines’, reinforcing routines’, ‘applying rules and sanctions’ and acknowledging and praising pupil effort’. The Behaviour Management Standard is specific, evidence-based and provides an outline for what could be incorporated a university course on behaviour management.

Conclusion

By developing a behaviour curriculum, schools have the potential to unlock more learning in every Australian classroom. Behaviour is a curriculum, and teachers must teach students how to behave. A behaviour curriculum must clearly set out the desired behaviours for students. The values that all students will experience in the school need to be clearly outlined and the routines and rules to be followed must be fully explained, as these are the building blocks to the culture of the school. The explicit nature of the teaching of behaviour must be described, as well as the consequences for unacceptable behaviour.

Student learning is an adult responsibility. The capacity for students to learn is determined by how well teachers manage their classrooms. This is why the federal government’s Expert Panel identified ITE students being skilled in classroom management as crucial. Classroom management is about practices and routines a teacher uses to create and maintain a classroom environment in which instruction and learning can take place efficiently.

If learning is the focus, then disruptive student behaviour is seen as any behaviour or action that impedes academic engagement or attainment. This focus on learning shifts the conversation with students to how their behaviour is interrupting their learning, the learning of others, and the instruction of the teacher.

A behaviour curriculum will provide clarity and consistency for students, staff, and parents to understand what is expected, leading to a more consistent behavioural environment. The focus on what is expected and the belief that students can behave in a classroom creates a more positive culture. Simple, easily understood routines make it easier for all students to participate in the culture of the school which leads to better academic focus and achievement. Importantly, teachers must have high expectations of students. High expectations are achieved when the values that underpin classroom norms, routines and rules are taught, modelled and followed up consistently.

Teaching students how to behave provides equity of learning that can overcome disparity due to geographical location or family background. Teacher-led classrooms that are calm, orderly, predictable and safe are a precondition to student learning. Predictable and consistent classrooms ensure that all students, irrespective of diversity or trauma, can participate in learning. Teachers being warm demanders highlights that classrooms are teacher-led. The teacher is the authority in the classroom that students are seeking. Teacher authority is based on responsibility and the need for students to experience a classroom where they feel a sense of belonging, realise they have talent, and grow in independence through responsible behaviour.

The outcomes that have been achieved at Michaela Community School in the UK are indicative that proper classroom management lifts learning outcomes. Founder and head teacher Katharine Birbalsingh says the teaching of behaviour, routines and rules has helped students from a variety of backgrounds achieve success. For example, in 2021, 97% of Michaela Community School students achieved a grade of 4 or better in English and Maths GCSEs, which is higher than the national average. She has also noted that a significant proportion of the school’s students come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and a large proportion have gone on to attend top universities.

The explicit teaching of behaviour in Australia will ultimately lead to achieving the goals of the 2019 Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Declaration by education ministers where “the Australian education system promotes excellence and equity and where all our children and young people become confident and creative individuals, lifelong learners, and active and informed members of the community.”

References

ACARA. (n.d.). Structure | The Australian Curriculum (Version 8.4). Retrieved April 29, 2023, from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/curriculum/structure/

Alter, P., & Haydon, T. (2017). Characteristics of Effective Classroom Rules: A Review of the Literature. Teacher Education and Special Education, 40(2), 114–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406417700962

Anderson, L. M., Evertson, C. M., & Brophy, J. E. (1979). An experimental study of effective teaching in first-grade reading groups. Elementary School Journal, 80(4), 193-211. https://doi.org/10.1086/461007

Angus, D., McDonald, T., Ormond, C., Rybarczyk, B., Taylor, M., & Winterton, A. (2009). Trajectories of classroom behaviour and academic progress: A study of engagement with learning. Australian Journal of Education, 53(3), 280-294. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494410905300306

Australian Education Research Organisation. (2006). Managing the classroom to maximise learning. AERO occasional paper series. Retrieved from https://www.aare.edu.au/data/publications/2006/aaa06_422.pdf

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2021) Classroom Management: Standards-aligned evidence-based approaches.

Australian Government. (2023). Strong Beginnings: Report of the Teacher Education Expert Panel

Beaman, R., & Wheldall, K. (1997). Teacher perceptions of troublesome classroom behaviour: A review of recent research. Special Education Perspectives, 6, 49-55.

Beaman, R., Wheldall, K., & Kemp, C. (2010). Recent research on troublesome classroom behaviour. In K. Wheldall (Ed.), Developments in educational psychology (second edition) (pp. 135-180). London: Routledge.

Bennett, T. (2017). Running the Room: The Teacher’s Guide to Behaviour. Routledge.

Berry Street Submission, (2023) Senate Inquiry into ‘The issue of increasing disruption in Australian school classrooms.’ Senate Education and Employment Reference Committee.

Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., Leaf, P. J. (2015). Examining variation in the impact of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports: Findings from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Journal of Educational Psychology, Volume107, Issue number 2. Pages 546-557.

Cook, C. R., Fiat, A., Larson, M., Daikos, C., Slemrod, T., Holland, E. A., Thayer, A. J., Renshaw, T. (2018). Positive Greetings at the Door: Evaluation of a Low-Cost, High-Yield Proactive Classroom Management Strategy. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, Volume20. Issue number3, pages 149-159.

Davis, B., & Simmt, E. (2006). Mathematics-for-teaching: An ongoing investigation of the mathematics that teachers (need to) know. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 61(3), 293-319.

Department for Education. (2022). Behaviour in schools: Advice for Headteachers and school staff. UK government publications.

Duhigg, C. (2012). The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. Random House.

Duhigg, C. (2012). The science of habit formation: What every leader should know. Harvard Business Review, 90(7/8), 48-54

Edward-Groves, C. (2012). Strategies for engaging young adolescents: Transforming the role of teacher as warm demander. Middle School Journal, 43(5), 4-12.

Elliot, S. N., & Busse, R. T. (1991). Behavior and academic achievement in mainstreamed students. Exceptional children, 57(3), 258-264.

Emmer, E. T., & Evertson, C. M. (2013). Classroom management for middle and high school teachers (9th ed.). Pearson.

Emmer, E. T., & Stough, L. M. (2001). Classroom management: A critical part of educational psychology with implications for teacher education. Educational psychologist, 36(2), 103-112.

Evertson, C. M., & Weinstein, C. S. (2006). Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues. Routledge.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Furrer, C., & Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 148-162. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.148

Giota, J., & Koustourakis, G. (2015). Developing a classroom management model to facilitate inclusion of students with ADHD. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(7), 733-749. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2014.957192

Hammond, Z. L. (2015). Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Corwin.

Harackiewicz, J. M., Rozek, C. S., Hulleman, C. S., & Hyde, J. S. (2012). Helping parents to motivate adolescents in mathematics and science: An experimental test of a utility-value intervention. Psychological science, 23(8), 899-906.

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning. Routledge.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of educational research, 77(1), 81-112.

Heffernan, A. (2019). Perceptions of teachers and teaching: A study of secondary school students in Ireland. Irish Educational Studies, 38(3), 329-347. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2019.1657876

Hernandez, E. P., & Oxford, R. L. (2006). Coaching for learning: A review of the literature. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(3), 226-243

Institute of Education Sciences. (2008). Reducing behavior problems in the elementary classroom: A practice guide. (NCEE #2008-012). U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Docs/PracticeGuide/behavior_pg_092308.pdf

Johnson, M., Oswald, A. J., & Adey, P. (1993). The Nuffield Science Project: a longitudinal study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 63(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1993.tb01002.x

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75-86.

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75-86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1

Kleinfeld, J. (1975). Effective classroom management: A teacher’s guide. Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children.

Kollar, I., Fischer, F., & Hesse, F. W. (2006). Instructional support for learning argumentation skills in the context of history. Learning and Instruction, 16(6), 539-557.

Kounin, J. S. (1970). Discipline and group management in classrooms. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Lally, P., Van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How habits are formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 998-1009

Linn, M. C., & Eylon, B. S. (2011). Science learning and instruction: Taking advantage of technology to promote knowledge integration. New York: Routledge.

McDonald, T. (2019). Classroom Management: Engaging Students in Learning. Oxford University Press.

National Council on Teacher Quality. (2014). Training our future teachers: Classroom management. Retrieved from https://www.nctq.org/dmsView/Training_Our_Future_Teachers__Classroom_Management_NCTQ_Report

OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en

OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 Technical Report. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en

Oliver, R. M., Webb, L. N., Wehby, J. H., & Reschly, D. J. (2011). Teacher classroom management practices: Effects on disruptive or aggressive student behavior. Retrieved from http://publications.ici.umn.edu/pdf/teacher-classroom-management-practices.pdf

Ormond, C., & Martin, A. J. (2013). Teacher–student relationships and classroom management. In E. Frydenberg (Ed.), Developing relationships in the classroom (pp. 25-42). Routledge.

Reeve, J. (2004). Self-determination theory applied to educational settings. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 183-203). University of Rochester Press.

Ryan, A. M., Gheen, M. H., & Midgley, C. (1998). Why do some students avoid asking for help? An examination of the interplay among students’ academic efficacy, teachers’ social-emotional role, and the classroom goal structure. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(3), 528-535.

Savage, G. C. (2018). Education Policy and the Australian Federal System. Australian Journal of Education, 62(1), 4-16.

Simonsen, B., Fairbanks, S., Briesch, A., Myers, D., & Sugai, G. (2008). Evidence-based practices in classroom management: Considerations for research to practice. Education and Treatment of Children, 31(3), 351-380. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.0.0023

Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., Dunlap, G., Hieneman, M., Lewis, T. J., Nelson, C. M., & Ruef, M. (2000). Applying positive behavioral support and functional behavioral assessment in schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2(3), 131-143.

Sullivan, C., Bradford, D., Behrens, J., Ross, S., & Middendorff, E. (2014). The Australian Behaviour Surveys. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66(3), 165-175. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12057

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257-285.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257-285. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4

Weinstein, R., Marshall, H. H., Sharp, L., and Botkin, M. “Pygmalion and the student: Age and Classroom Differences in Children’s Awareness of Teacher Expectations,” Child Development, vol. 58, no 4 (August 1987):1079-1093.Wong, H. K., & Wong, R. T. (2018). The First Days of School: How to Be an Effective Teacher. Harry K. Wong Publications.

Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2007). A new look at habits and the habit–goal interface. Psychological Review, 114(4), 843-863

Two Related Works

Katharine Birbalsingh. How progress teaching is failing students. November 15, 2022. CIS Occasional Paper OP 192.

Blaise Joseph. Getting the most out of Gonski 2.0: The evidence base for school investments. October 14, 2017. CIS Research Report 31 RR 31.