Foreword

The success of Australia’s cohesive and multicultural society over the past sixty or more years has depended on a simple compact: in return for the citizen being free to maintain private cultural and religious traditions, the state expects observance of our norms and laws. However, since Hamas’s invasion of Israel on 7 October 2023, this compact has been under unprecedented strain as the politics of the Middle East erupted on to the streets of our cities.

Nearly one year later (at the time of writing), these tensions are getting worse. The tolerance and diversity of which we have been rightly proud has given way to cultural separatism and open, often violent, conflict between different groups. Politicians’ warnings that levels of intolerance are on the rise are coded warnings that social disintegration is upon us. Many people are now wondering whether we are witnessing the end of Australia’s multicultural project.

But if not the end, then what kind of future lies ahead for Australian multiculturalism? More than 10 years ago, the Centre for Independent Studies published a report that examined the health of our multicultural society. In Multiculturalism and the Fetish of Diversity, the present author argued the narrow promotion of diversity as moral objective — rather than as a political outcome — posed a long-term threat to individual liberty. It did so by promoting the interests of particular groups over those of the individual by means of what the report described as “programmatic” or “hard” multiculturalism.[1]

Striking a balance between ‘diversity’ and a cohesive national culture that binds all citizens of a society is not easy; especially in a country such as Australia, which has enjoyed sustained periods of high immigration. The balance requires a commitment on the part of governments, political and community leaders, teachers, families and the individual citizen to a greater whole — the nation state. For the most part, this balance has been struck in Australia successfully. But what happens when it is distorted? What kind of future can lie ahead for multiculturalism in this country?

The three essays in this collection attempt to answer that question. Damien Freeman and Jonathan Cole, who were invited to respond to the first essay, written by the present author, take different approaches to the issue of multiculturalism. Freeman argues that social cohesion depends on cultivating trust, which he considers to be greatly diminished; Cole argues that a strong and free market economy is the best way to foster social cohesion. Both take issue with the present author’s argument for the need for multiculturalism to be grounded in a stronger national identity. What all three essays have in common is the recognition that there is a problem with Australian multiculturalism and it is a problem that can no longer be ignored.

In his Afterword, Bryan Turner responds to the three essays and adds what he considers the crucial ingredient of ‘populism’ to the multicultural mix. Turner argues that populism, which characterises as “opposition to the diversity caused mainly by immigration”, is both a product of democracy and also its greatest threat. “Does this contradiction characterise modern Australia?” Turner asks. He holds that it does, and that if we care to preserve both diversity and liberty, we have to address populism and the challenge it presents.

The Future of Australian Multiculturalism presents a series of complimentary, if distinct, assessments of the health of our national multicultural project. As such, it is intended as a contribution to the conversation we are bound to have if we are serious, as a nation, about sustaining and strengthening the social cohesion for which Australia has long been so noted.

Peter Kurti

Director – Culture, Prosperity & Civil Society program

The Centre for Independent Studies

Diversity As Division Or Unity? The post-multicultural threat to Australia’s liberal democracy

Peter Kurti

When ‘diversity’ crossed the floor

Australian multiculturalism has been dependent on a simple compact: integration of cultural diversity is a shared responsibility between Australian citizens (or citizens-to-be) and the Australian state. At the heart of this compact lies an expectation — even an assumption — that the individual will observe Australian norms and laws, and that the state will, in turn, afford the individual freedom privately to maintain certain cultural and customary norms and traditions.

However, the eruption of pro-Palestinian and antisemitic protests following the attacks of 7 October 2023, together with consequent bitter political division and polarisation, have raised serious questions about the success of Australia’s multiculturalism model. Far from fostering social cohesion and the civic virtue of tolerance, multiculturalism appears to have encouraged cultural separatism and helped fan hostility between different sections of the community.

The politics of the Middle East have also cleaved open the politics of our own country. The issue of Palestinian ‘statehood’ ruptured the party room unity of the federal Labor government when WA Senator Fatima Payman defied caucus and crossed the floor of the chamber to vote against ALP policy on the Palestinian issue. Palestinian statehood is also now the principal issue fuelling the emergence of a new political entity in Australia: The Muslim Vote. This organisation claims on its website to represent the interests of Australian Muslims who “are a powerful, united force of nearly one million acting in unison.”[2] The Muslim Vote rates politicians according to a series of criteria; none of which are about Islam or issues affecting Australian Muslims. All the criteria are about Palestine.[3]

When Payman crossed the floor, she complained that the pressure brought to bear upon her by her parliamentary colleagues put the lie to any commitment to ‘diversity’ of representation in Australian society when there was no accompanying diversity of opinion. “It is important to consider that modern Australia looks very different to what it did 20-30 years ago and will continue to change,” Payman said.[4] These remarks about diversity raise an important question for advocates of Australian multiculturalism: Is ‘diversity’ simply a descriptor of the multi-ethnic character of society or does it point to the emergence of parallel societies in Australia? Payman’s use of the term suggests ‘diversity’ is being prioritised as a social norm and used as a weapon against prevailing social, political and cultural structures in our society.

These structures came under further attack when Australian democracy, and The Muslim Vote, itself, were subsequently denounced by Islamist Muslim clerics as an insult to Allah. The clerics also denounced Muslim members of Australian parliaments as “apostates” and declared that what the clerics sought was a different form of power that would enshrine sharia as the dominant form of law in Australia.[5]

Declarations such as this openly and directly challenge the political, legal and social norms of this country. They also call into question the viability of the compact upon which Australian multiculturalism has always depended. Tolerance of diversity in Australia is only possible if bounded by a commitment to the spirit of Australian law and order. This entails, in part, that Australian streets, parks and campuses do not become the arenas in which overseas conflicts are played out. And yet this is precisely what appears to have happened.[6]

Multiculturalism and the promotion of diversity was originally intended to counter the ‘whiteness’ of Australian society that was a legacy of its founding. Diversity is now being deployed not only to assault any Australian norms with which it is deemed to conflict, but also to foment conflict between Australia’s ethnic communities. And herein lies the threat posed by multiculturalism to Australia’s secular liberal society. Today, the stakes have never been higher for the future of Australian multiculturalism. Indeed, the strains generated by Australian multiculturalism, as we have known it for 50 or more years, appear to be driving the emergence of a form of post-multiculturalism that could supersede it.

Multiculturalism in Australia

In one sense, ‘multiculturalism’ simply refers to cultural diversity in a society in which different cultural, social and religious communities coexist. One of the most culturally diverse countries in the world (ranked third after Singapore and Hong Kong), Australia has seen the proportion of its population born overseas rise steadily during the first quarter of the 21st century. In 2001, the figure stood at 23 per cent; by 2011 it had risen to 26 per cent; and by 2023, it had risen again to 31 per cent; which means about 8.2 million people, in a total population of 27 million, were born overseas.[7]

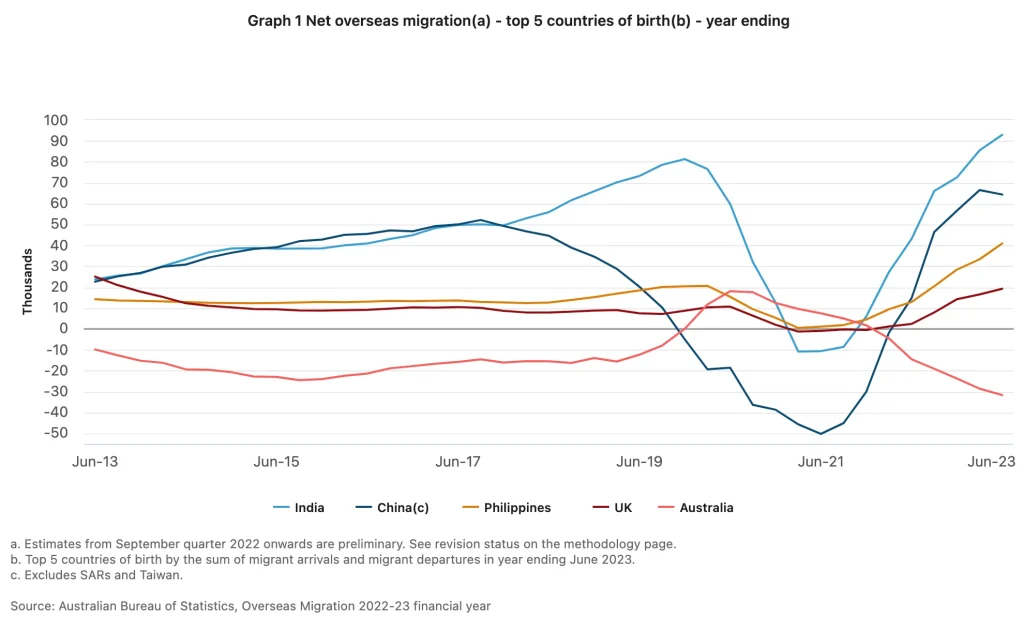

Australia’s immigration has always been higher than emigration in comparison with other countries (see Graph 1). Thus, net overseas migration (NOM), which represents the net gain of immigrants arriving minus migrants departing, has always been a significant source of population growth in Australia. In 2023, NOM amounted to 518,000 people who were added to Australia’s population, accounting for 84 per cent of the country’s population growth, the largest NOM since records began.[8]

As will be discussed below, research by the Scanlon Foundation’s Mapping Social Cohesion survey shows Australians remain broadly content both with this kind of multiculturalism, which is the result of these levels of immigration, and with the benefits that flow from cultural diversity. Thus, the crisis now confronting multiculturalism in Australia does not arise from immigration, as such, but rather from the behaviours and attitudes some groups of migrants and their descendants are explicitly directing at other groups in the Australian community.

This leads to consideration of a second sense of ‘multiculturalism’ that is pertinent to an evaluation of Australia’s form of multiculturalism. This second sense refers to a program of government policy that employs certain mechanisms for promoting cultural diversity, ranging from subsidy to preferential treatment.

This form of programmatic multiculturalism developed in Australia as a policy response to issues relating to the settlement and integration of immigrants in ways that cohered with prevailing norms while affording new arrivals greater acceptance of their own social and cultural practices. The Whitlam government (1972-75) initiated some of these policy responses.

In his famous 1973 speech as Labor’s then immigration minister, ‘A Multi-cultural Society for the Future’, Al Grassby, said “the social and cultural rights of migrant Australians are just as compelling as the rights of other Australians.” Grassby developed the policy goal of multiculturalism as ‘unity in diversity’ which expressed a strong commitment to the moral principles of equity and reciprocity: dissimilar people in a voluntary bond agreeing to share a common social structure.

Multiculturalism in Australia began to take its present form under the Fraser government (1975-83). The landmark Galbally Report, released in 1978, established four guiding principles of multiculturalism: equality of opportunity; the right to express one’s own culture; ethno-specific services; and self-help for migrants. These principles were further developed in 1982 in a series of forums around the country initiated by the Fraser government and led by George Zubrzycki.

Four themes of multiculturalism emerged from Zubrzycki’s work: social cohesion; cultural identity; equal opportunity and access; and equal responsibility for participation in society.[9] As Australian academic Laksiri Jayasuriya has observed, the Australian model of liberal multiculturalism conjoined the notion of ‘inclusionary citizenship’ (which conferred the rights and privileges of citizenship) with ‘cultural pluralism’. However, Jayasuriya also warned that:

Running through this was a tension that indicated that multiculturalism was conditional, in that mutual coexistence of different cultures was permissible only provided there was an acceptance by new settlers of the commonalities embodied in the Australian political system and its social legal institutions.[10]

In the decades after the Fraser government, Australian multiculturalism went beyond the liberal position that the law must protect the liberties of citizens to enjoy freedom of association; rather, it emphasized “the need for action to modify or change social attitudes, and to alter the distribution of economic resources, and indeed the distribution of political influence.”[11] It was characterised by a commitment to cultural pluralism with its emphasis on equal treatment and the insistence that no cultural norms should enjoy priority over any others.

Today, this commitment is expressed through the work of a series of organisations and bodies that focus on promoting multiculturalism and social cohesion. These include:

-

- The Australian Multicultural Council, which comprises ministerially appointed members who give independent advice to government on multicultural affairs, social cohesion and policies for promoting integration.

- The Australian Multicultural Foundation established nearly 40 years ago to forge a strong commitment to Australia while respecting cultural diversity.

- Multicultural Australia, which promotes multiculturalism and social cohesion in Queensland. The comparable body in NSW is Multicultural NSW.

- Ethnic Communities’ Councils, which operate across the country in various states and territories to promote social cohesion at local levels.

- The Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils of Australia, which advocates for multicultural policies at a national level.

Some of these bodies are publicly funded, others operate as private companies; all seek to promote the principle of multicultural diversity, but do so without seeking so much preferential treatment as what they consider equal treatment for Australia’s ethnic communities.

Multicultural organisations invariably express a commitment to the importance of common membership of a political community that shares a history, and legal and political institutions. However, intensity of that commitment is weakened whenever this form of programmatic multiculturalism places greater emphasis on cultural diversity than national identity. As Jayasuriya has remarked, the emergence of these organisations over time helped generate “an identity politics that became the orthodoxy of Australian multiculturalism.”[12]

The Howard government (1996-2007) made efforts to reframe multiculturalism in terms of commitment to the idea of the ‘nation’. With an emphasis on duties rather than rights, the government sought to assert the idea of core Australian values to which all Australians, including new settlers, needed to commit. Concerns grew that promoting the idea of all cultures as equal posed a long-term threat to social cohesion. By 2024, the impact of identity politics on Australian society had played out in ways that many would have found difficult to anticipate 10 or 15 years before.

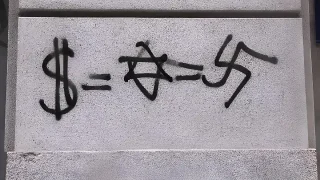

One impact, witnessed with particular intensity since 7 October 2023, is violation of the axiom that ethnic communities do not bring to these shores conflicts from their countries of origin. One alarming manifestation of this is the eruption of antisemitism, which some leaders in politics and commentators in the media have been slow to denounce. In a recent speech delivered at the University of NSW, Steven Lowy, a former co-chief executive of Westfield Corporation, expressed concern “that Australia is now sleepwalking into a period of extremist politics and a social spiral.”[13]

While tensions between communities are bound to arise, they must not spill out into open hostilities; yet this is precisely what has now happened. Worse still for the prospects of Australian multiculturalism has been the assertion of group rights as opposed to those rights to be enjoyed by individuals. As Lowy also remarked, “We can disagree with each other without collectively demonising a people based on race or religion. [But] it is a sad fact that there has generally been lukewarm denunciation of anti-Semitism [sic], at best by the leadership of many of our institutions. Half-hearted rejection of anti-Semitism is never enough, as history has shown all too well.”[14]

Clearly, the issue of pluralism arises because of the large migrant component of the Australian population. But the resurgence of antisemitism is not the direct result of immigration; it is the result of a systemic failure to manage integration and defend the paramount importance of what might be described as ‘national values’ in an increasingly diverse society. Thus, the paradox of pluralism — “the dilemma of having to reconcile commonalities with ‘difference’”[15] — has become more acute. As leading commentator Paul Kelly puts it:

Australian multiculturalism has fallen victim to a self-congratulating complacency and a dramatic shift in progressive ideology. The more the left promoted a tribal and identity politics based on race, ethnicity, religion, sex and gender, the more it attacked the principles of multiculturalism by encouraging the growth of separate group rights. This inevitably led to social and political fragmentation. Group rights become the new mantra, weakening the power of national harmony.[16]

Do Australians still want multiculturalism?

Despite concerns such as those raised by Kelly and others, the Australian model of multiculturalism has been, for the most part, successful. Most of us think it’s been good for the country; and most of us want it to continue. The most authoritative account of Australian attitudes to multiculturalism is provided by the Scanlon Foundation’s annual Mapping Social Cohesion (MSC) report.

According to the 2023 MSC Report, compiled before the war in Gaza began, 89 per cent of Australians agreed with the statement: “multiculturalism has been good for Australia.”[17] Not only is this figure consistently high across MSC surveys in recent years, it has been rising: in 2018, 77 per cent of respondents agreed with the same statement; in 2022, 88 per cent agreed.

These views are coupled with a very favourable view of the value immigrants are thought to bring to Australia, both in social and economic terms. Over 90 per cent of respondents agreed that “someone who was born outside Australia is just as likely to be a good citizen as someone born in Australia.”[18] As the MSC remarks:

The very strong support for the view that multiculturalism has been good for Australia suggests that multiculturalism is an important symbol and holds great value to people across a broad cross-section of society.[19]

However, when it comes to the question of whether or not immigrants are ready to adopt Australian values, respondents were divided. In 2023, 53 per cent of respondents believed too many immigrants were not adopting our national values, albeit a significant decrease from 67 per cent in 2019. Although a large proportion thinks migrants are adopting values, “a large share of people still do not think that is the case.”

Further, the 2023 MSC Report also found prejudice remains a common problem in Australia, and Christians and Muslims are the people about whom most others hold negative attitudes. Even so, the MSC detected a widespread decline in negative attitudes towards Muslims from 41 per cent in 2019 to 32 per cent in 2023.[20]

Whereas respondents held positive attitudes to migrants from the United Kingdom (91 per cent), the United States (92 per cent), Italy (94 per cent) and Germany (79 per cent), attitudes towards other migrant groups were found to be negative. Thus, 63 per cent held negative attitudes to migrants from Asia, the Middle East and Africa, prompting the MSC to remark that:

This striking discrepancy in the attitudes expressed towards European (and US) and non-European migrants is a worrying indicator of the potential racial prejudice held within Australia.[21]

The 2023 MSC therefore makes two seemingly contradictory claims: on the one hand, that multiculturalism remains popular in Australia and that Australians value the contribution migrants make to the country; but on the other, that there are worrying indicators about racial prejudice. Noting that multiculturalism can be understood in different ways, the MSC found only 37 per cent of Australian-born respondents believed minorities should be given government assistance to maintain customs and traditions. By marked contrast, 69 per cent of overseas-born respondents supported government assistance.

Attitudes to multiculturalism are related strongly to levels of social cohesion: “people who are happier, more financially satisfied, more trusting in political leaders and more involved in community and civic activities” tend to have much more positive attitudes to multiculturalism.[22] Even so, given the varied understanding of what multiculturalism is, and varied levels of acceptance according to socio-economic status, Australian multiculturalism appears to be a work in progress.

A pressing question is whether that progress has faltered because of a clash between the pursuit of diversity and the principles of liberalism and a liberal society. The decisive defeat of the Voice proposal in the October 2023 referendum certainly suggests popular enthusiasm for diversity might be on the wane. However, one important and more recent opportunity to address this question, appears to have been missed by the Australian government.

Towards fairness?

In 2023, 50 years after Grassby’s speech outlining a vision for Australia’s multicultural future, the Albanese government commissioned a review of multiculturalism that outlined 29 recommendations and proposed a policy framework. The report, delivered in March 2024 but not made public until July, acknowledged social circumstances had changed since 1973 and “the beliefs and concepts we previously counted on for stability are being put into question” by those changing circumstances.[23]

Recommendation 11 of the report called for the government to establish a Multicultural Affairs Commission and Commissioner together with a new Department of Multicultural Affairs, Immigration and Citizenship, with a dedicated minister.[24]

Many of the other recommendations concerned matters of resourcing, ensuring and widening provisions to encourage the embracing of ‘diversity’, including providing for citizenship tests to be conducted in languages other than English. The report made no mention of the resurgence of antisemitism in Australia since October 2023, nor did it address the overt hostility of sections of the Muslim community to the institutions and norms of Australian society.

Opposition citizenship spokesman, Dan Tehan, criticised the report for failing to address social cohesion when it had been commissioned at a time when, in his view, “social cohesion in this nation has never been challenged like it is at the moment”. Tehan added: “The fact that anti-Semitism [sic] isn’t addressed in this report leaves the question: what of the recommendations, if any, can be taken seriously?”[25] At the time of writing (October 2024), the Albanese government has made no commitment to implementing any of the report’s recommendations.

Even were it to do so, a prior and urgent requirement is to ensure any framework for Australian multiculturalism sits beneath a wider national commitment to social cohesion, the institutions of our parliamentary democracy and the norms and principles of a liberal and secular society. Questions about the fundamental compatibility of multiculturalism and liberalism must be addressed if a genuinely diverse and cohesive society is to be forged.

The individual and the group

“Has multiculturalism been a success or are we a nation of parallel communities?” sociologist Bryan Turner asks of contemporary Australian society.

While the idea of multiculturalism as a social policy tends to focus on culture, a more acid test arises with legal pluralism. Competing legal traditions necessarily raise more acute difficulties than cultural pluralism, as the former brings the nature of sovereignty into play.[26]

A central issue when evaluating the prospects for multiculturalism in Australia is whether multiculturalism in its ‘hard’ or policy-driven form is compatible with liberalism and the liberal state. The idea of the ‘liberal state’ can be understood in the clear and concise terms offered by William Galston, an American political scientist who has remarked it:

Is characterised as a community organised in pursuit of a distinctive ensemble of public purposes. It is these purposes that undergird its unity, structure its institutions, guide its policies and define its public virtues.[27]

According to Galston, the liberal state is not neutral: its ‘ensemble of public purposes’ will be informed by a certain conception of justice, for example, which will, in turn, limit and shape possibilities available to its citizens. It will also shape the state’s understanding of its own interests and preferences. One dimension of these interests and preferences is liberalism’s commitment to what legal scholar Daniel Weinstock has identified as ‘political individualism’; by which he means the state can only be justified to the extent it serves the good of the individual:

Whether that good is cashed out in terms of individual interest, individual consent, or in terms of some more morally ambitious notion such as individual flourishing, is one of the questions that liberals argue about. However, this core commitment is sufficient to generate the view, common to all liberals, that groups cannot be viewed by liberalism as possessed of any kind of irreducible value. Groups matter only to the extent that they matter to individuals.[28]

But the primacy of the commitment contemporary liberalism affords to the individual is not without its problems.

In the view of American political scientist John Owen, this commitment poses a threat to the integrity of the individual. This is because what Owen describes as “open liberalism” — using the term ‘liberalism’ to refer to “a commitment to individual freedom as the highest political good”[29] —grants to the individual the freedom to engage in perpetual creation by means of exercising that very freedom to choose. The result of this continual exercise of choosing, Owen argues, is that liberalism today has come to represent:

A dogmatic rejection of all boundaries, material or social, particularly inherited ones. It presses upon us a novel notion of the good life as a life of perpetual choice and fluidity across all conceivable areas, private and public, from cradle to grave.[30]

Owen argues that the “enforced fluidity” brought about by open liberalism has led both to the dissolution of institutions (he cites the example of marriage) and the ability of those institutions to command loyalty because the norms and boundaries that sustain them have weakened. Owen calls for a revision of liberalism towards what he calls “pluralistic liberalism” which will restore to the individual the capacity “to bind [oneself] to norms, communities and ways of life that require long-term commitment.”[31]

By urging liberalism to become more pluralistic, in the sense of affording the individual the opportunity freely to adopt whatever social and cultural constraints are deemed of value, Owen’s criticism serves to sharpen liberalism’s focus on the freely-choosing individual as the possessor of irreducible value. Whereas one individual is free to throw off all constraint, another is free to choose to be bound by established and inherited norms and conventions. Pluralistic liberalism, in this sense, thereby preserves the primacy of liberalism’s commitment to the individual. This, in turn, entails that the group can only matter to the extent it comprises individuals.

Whether one embraces the open or the pluralistic conception of liberalism, it still holds that groups cannot give rise to independent moral claims. If liberalism can confer anything in the group, it is only “the full complement of individual rights which are essential building blocks in the associational lives of individuals.”[32]

Thus the fullest involvement of the liberal state in the lives of its citizens ought to entail protecting the rights of individuals freely to associate or dissociate, and to uphold the liberal principle that the individual will have a certain conception of a good life and will want to live in accordance with that conception.

The individual is not, of course, an isolated unit. Individuals belong to groups; whether social, cultural, religious or some other. The culture of the group, in turn, shapes the identity of the individual by providing a perspective from which to interpret the world in which the individual lives. Any conception of a good life will, itself, be shaped by the various influences of the groups to which the individual belongs. What the liberal state must afford is equal respect to the individual by not coercing that person to act “in accordance with the choices and values of another individual”.[33]

Furthermore, a liberal society must protect the freedom of the individual to choose not to belong to a group or to be bound by its cultural, moral or religious norms and expectations, as C.L. Ten has observed:

A liberal community is a political community and a series of smaller social communities, with overlapping memberships, interacting with one another in a free environment. In a liberal society, [individuals] are free to leave [a group] and to try to join other groups. Those whom the dominant groups will not embrace can still find a home in a liberal community, and justice will be their shield.[34]

As long as the individual is capable of exercising autonomous agency and can enjoy protection of fundamental rights — whether within the group to which he or she belongs, or outside the group if the individual chooses to leave — tension between liberalism and multiculturalism ought to be minimal. However, at this point liberalism might come into possible conflict with the principles of policy-driven forms of multiculturalism.

Once the group makes claims for the exercise of its own autonomy with regards to those areas of social, cultural and political life that it claims to be of importance to its own way of life — notwithstanding conflict with the claims of individual members of the group — the principles of liberalism and multiculturalism are bound to collide.

Is multiculturalism compatible with liberalism?

One response to the issue of conflict that can arise between the individual and the group is that a society should demand some degree of homogeneity in order to bind citizens to one another as members of a single political community. In examining this response, Chandran Kukathas cites the position of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose view was that the state must express the general will of the people understood as individual and equal citizens.

According to Rousseau, there has to be “a profession of faith which is purely civil and of which it is the sovereign’s function to determine the articles, not strictly as religious dogmas, but as sentiments of sociability, without which it is impossible to be either a good citizen or a loyal subject.”[35] In other words, to the extent to which the values of the individual conflict with the values of the community, there can be no value pluralism when it comes to preservation of the political community of the state.

For Kukathas, this is a minimal conception of homogeneity. He holds that the question of whether a society should be multicultural is not a significant issue: “modern societies, for the most part, simply are multicultural. The important question that does raise significant issues is this: what kinds of political institutions should govern a multicultural society?”[36]

Kukathas rejects what he calls “interest-group pluralism” — the institution of political recognition of the pluralist elements in a multicultural society — because he does not think they merit participation in the political process: “political institutions should, as far as possible, serve to allow these different elements to flourish but should not be in the business of enabling these elements or interests to shape society.”[37] He argues political institutions should be neutral as to how a society is shaped by its component elements.

Whereas these elements — which include culture and ethnicity — will inevitably shape the lives of individuals living in particular communities, Kukathas believes these influences belong in the private realm. Political institutions should not permit the elevation of these influences to become matters of public concern where they become contestable. Rather, political institutions should be concerned simply with upholding the rights and freedoms of individuals “regardless of the particular interests or affiliations of the individuals.”[38] The focus, in other words, is not to be on group pluralism but on the pluralism of individual interests.

Even so, emphasising a liberal commitment to protecting individual freedoms and rights has not allayed concerns about the future of multiculturalism. Critics claim it is failing because it continues to give too much weight to protecting and promoting group identities and legitimating a retreat into separated minority communities, thereby generating communal and ethnic tensions. These concerns have given rise in the minds of some scholars, such as Steven Vertovec, to the need to rethink multiculturalism and even to posit the notion of an emerging ‘post-multiculturalist’ world.

‘Post-multiculturalism’ is something of an open-ended term. It is characterised, in part, by programs of corrective measures (such as some of those contained in the Towards Fairness report) intended to support language services, improve access to community services and review courses and tests for citizenship.

At the same time, the term ‘post-multiculturalism’ acknowledges that the terms of the compact between state and citizen have changed. These changes have arisen as the concept of multiculturalism has come under political pressure because of community concerns about perceived failures of integration, a sense of weakening social cohesion and the need for commitment to some concept of national identity. As Vertovec has remarked:

Despite a strong emphasis on conformity, cohesion, national identity and dominant cultural values, in practically all the contexts in which such policies are being implemented an acceptance of the significance and values of diversity is voiced and institutionally embedded. In this way, post-multiculturalist policies and discourse seek to have it both ways: a strong common identity and values coupled with the recognition of cultural differences.[39]

Reassertion of a strong sense of national identity has featured prominently in much recent criticism of multiculturalism. However, critics such as Kukathas have given little weight to the idea of a distinctly Australian national identity other than in a weak form based on a history and a shared inheritance of a set of legal and political institutions; it makes no reference to any “common ethnicity or ‘character’”.[40]

Once these institutions affirm the freedoms and rights of the individual, a society should be able to accommodate different cultural communities without asserting a strong sense of national identity that would, in any case, threaten to distort the diversity of identities in a society and possibly exclude certain individuals and communities. As Kukathas notes: “it is only by not creating too strong a sense of national identity that it will be possible to tolerate a variety of ways of life within the political community.”[41]

What next for Australian multiculturalism?

The success of Australian multiculturalism hitherto has been secured by observance of the simple compact outlined at the beginning of this essay: “integrating cultural diversity into Australian life is a shared responsibility of both the Australian government and Australian citizens or citizens-to-be.”[42] However, this compact — dependent on an acceptance of mutual responsibilities — has recently come under strain.

As recently as 2017, a policy statement issued by the Turnbull government emphasised the obligations of citizens and new arrivals to contribute to the life of the nation.[43] In doing so, the statement “jettison[ed] the language of government responsiveness to diversity, the cornerstone of Australian multiculturalism for over four decades. With the 2017 multicultural policy, the longstanding ‘nation-building’ idea of pro-actively accommodating cultural diversity is officially ended.”[44]

According to Australian political scientist Geoffrey Brahm Levey, the position of the Turnbull government’s policy can appropriately be described as ‘post-multicultural’. Levey chooses to use this term because he argues that the 2017 policy outline rests on the assumption that multiculturalism has “already redressed the historical exclusion of cultural minorities [and that] a sufficiently level playing field, institutionally and attitudinally, exists.”[45]

For Levey, this post-multicultural posture assumes the various policies for multiculturalism have now successfully done their job of transforming Australian society. However, it is Levey’s view, that Australia is nonetheless not yet ready to cut loose entirely from a multiculturalism committed to implementing group-differentiated measures, and that the post-multiculturalism attempted by the Turnbull government was “premature”.[46]

Whereas the Turnbull government’s policy proposal shifted the responsibility from the state to the citizen, by 2024, with the Albanese government’s Towards Fairness report, the emphasis swung back to government and the services it can — or should — provide to citizens and citizens-to-be. There is little mention now of shared responsibilities; the onus of obligation as set out in the report has returned to the shoulders of government.

Resurgent antisemitism in the wake of the 7 October attacks on Israel has raised grave concerns about the prospects for Australian multiculturalism. Indeed, in the opinion of Kelly, “the Australian values of multiculturalism, mutual respect, truth and social order are being traduced” as the changes in our society following the attacks continue to unfold. “The nation suffers from polarisation yet also denial.”[47]

Australians have been appalled by regular denunciations of their Jewish compatriots who, for the first time in living memory, are now fearful of walking the streets of their own cities. This has reignited debates about whether efforts directed at maintaining culture have taken priority over emphasis on the importance of strengthening social cohesion. One year on from the attacks, and after anti-Israel protest marches in key cities over more than 50 consecutive Sundays, Australia is witnessing an unparalleled poisoning of community relations by the hatred engendered by the politics of the Middle East. At the time of writing (October 2024), these protests have evolved into overt and explicit support for Hezbollah, a listed terrorist organisation.[48]

Although these attacks by one group of Australian citizens against another group are certainly alarming, the questions to which they have given rise are not new. Since its inception, debates about multiculturalism have oscillated between the poles of recognition of cultural diversity and commitment to common national norms such as the rule of law. As legal affairs commentator Chris Merritt has remarked of the importance of institutional commitment to enforcing the rule of law in Australia:

Respect for the rule of law comes naturally to most people in this country. But the principles that form the basis of that idea might not come naturally to those who have grown up in countries with a different tradition. The first step toward preventing lawless conduct is to ensure those who are subject to the law are made aware of their obligations – particularly those from different traditions.[49]

Australian multicultural policy has always been dynamic as it has sought over the years to respond to changing social and cultural circumstances. Once again, the parameters of multiculturalism are being debated: publication of Towards Fairness represents the most recent response to the ongoing challenge of managing an accommodation between cultural diversity and the principles of a secular liberal society. In a development that signals the possibility of an emergent post-multiculturalism, the focus has shifted sharply to concerns about social cohesion. Threats to the safety of one section of Australian society posed by other sections have also revived discussions about imposing limits on freedoms associated with a liberal society, such as freedoms of speech, association and religion.[50]

There can hardly be any prospect of urging Australian governments to scrap multicultural policies, given the diversity of the national population. Multiculturalism has developed from the fact that Australia is now a heterogeneous country that continues to attract large numbers of immigrants. And in addition, as Israeli professor of law Amnon Rubinstein has remarked: “New concepts of equality among different communities and of collective rights [have given] rise to a new philosophic-social-legal concept which has shaped public opinion.”[51] The fact is that multiculturalism now has deep roots in Australian society.

However, Towards Fairness clearly leans heavily away from affirming the value of a polity unified by a set of binding liberal principles and associated rights and duties, in favour of promoting a variegated society which places diminished emphasis on the value of overarching norms and institutions.[52]

Notwithstanding the concerns that commentators such as Kukathas have expressed about ‘national identity’, the current crisis of Australian multiculturalism almost certainly warrants renewed emphasis on the importance of commitment to the nation’s norms, laws and institutions. This problem will not be addressed by the creation and funding of more multicultural bodies and policies, for this is to assume fundamental social and cultural attitudes can be shaped by institutional bureaucracies alone. Rather, the current crisis of Australian multiculturalism needs to be addressed by what Stephen Lowy has described as “a return to strong conviction leadership:

Leadership is about conviction. Leadership is not about popularity. It is about doing what is fundamentally right for the country. And we are seeing this slipping in Australia now. We live in an age of conviction deficit. And once you create a little crack, you give licence. We are now paying a high price for that.[53]

Citizens of this country must commit to Australia and its way of life, and fears that calling them to do so may stir division must be quelled. Yet, as Lowy has remarked, without effective political leadership that sets the terms of the discourse about culture, this is likely to amount to little. This is a view shared by commentators such as Kelly who is more outspoken in his criticism of the Albanese government for having failed “to show the moral, social and strategic leadership that Australians deserve.”[54]

At the same time, a lingering concern is that today’s generation of political leaders have been formed by immersion in a 50-year program of cultural pluralism and diversity, so are ill-equipped to provide the leadership so urgently required if multiculturalism in Australia is to have a future. This program of cultural pluralism, which has been promoted with vigour by our schools and universities over the course of a generation or more, has downplayed the importance of common norms and values. The bitter fruit of that policy failure is now being served up.

The danger is that the leaders on whom we must depend will fail to grasp the critical role government must play in enforcing duties of shared responsibility and mutual tolerance. And if that is the case, Australian multiculturalism will inadvertently, and perhaps inevitably, sink from damage of its own creating.[55]

Unity or Belonging? The post-White Australia approach to Australia’s social cohesion

Damien Freeman

Writing in The Spectator, John Casey recalled a time when Margaret Thatcher and Enoch Powell both attended a meeting of the Conservative Philosophy Group:[56]

Edward Norman (then Dean of Peterhouse) had attempted to mount a Christian argument for nuclear weapons. The discussion moved on to ‘Western values’. Mrs Thatcher said (in effect) that Norman had shown that the Bomb was necessary for the defence of our values. Powell: ‘No, we do not fight for values. I would fight for this country even if it had a communist government.’ Thatcher (it was just before the Argentinian invasion of the Falklands): ‘Nonsense, Enoch. If I send British troops abroad, it will be to defend our values.’ ‘No, Prime Minister, values exist in a transcendental realm, beyond space and time. They can neither be fought for, nor destroyed.’ Mrs Thatcher looked utterly baffled. She had just been presented with the difference between Toryism and American Republicanism. (Mr Blair would have been equally baffled.)

What is it that we would fight to defend? Shared values? Diversity? The country to which we belong? The answer goes to the heart of the question of what makes us willing to cooperate as a society to ensure we survive and prosper.

Programmatic multiculturalism and liberal democracy

Peter Kurti distinguishes between multiculturalism as a descriptive claim about a society’s cultural diversity and programmatic multiculturalism, which treats multiculturalism as “a program of government policy which employs certain mechanisms for promoting cultural diversity ranging from subsidy to preferential treatment”. This programmatic multiculturalism came, he argues, to be dominated by identity politics. While Kurti accepts that the Australian population is still positively disposed towards Australia’s cultural diversity, he observes that it trends away from programmatic multiculturalism and identity politics.

In 2023, the Albanese government commissioned a review of multiculturalism which resulted in the Towards Fairness report published in mid-2024. Kurti observes that the Towards Fairness recommendations would enshrine group rights in Australia’s public institutions. His concern is that this would be a radical departure from the status quo, in which the fundamental basis of liberal democracy is the relationship between the individual citizen and the state. Liberal democracy would be disturbed, he argues, if the institutional relationship between the state and the individual was mediated by some notion of groups through which the state engages with individuals who identify with those groups. This leads Kurti to conclude that multiculturalism is incompatible with liberalism.

If the ultimate expression of multiculturalism is found in Towards Fairness’s institutions through which identity groups mediate the relationship between the individual citizen and the state, then multiculturalism is indeed incompatible with liberal democracy. Thus, Kurti concludes that multiculturalism in Australia is in trouble. He notes that the Turnbull government tried to reset the approach to multiculturalism by reframing it in terms of citizens’ responsibilities in concert with the rights they might assert, but this did not get traction. The most recent approach of enshrining programmatic multiculturalism and identity politics in the Towards Fairness report is roundly criticised by Kurti as being incompatible with liberal democracy and, at any rate, does not even seem to have been appealing to the current progressive government.

So what is the solution? Kurti does not claim to have it, although he does gesture towards it: “the current crisis of Australian multiculturalism almost certainly warrants renewed emphasis on the importance of commitment to the nation’s norms, laws and institutions. Citizens of this country need to commit to Australia and its way of life, and fears that calling them to do so may stir division need to be quelled”.

What is missing from this analysis is a deeper understanding of the purpose of multiculturalism as a public policy in Australia today. In order to understand multiculturalism’s purpose, one needs to see it as a response to an earlier public policy: the White Australia policy. Only when it is located in this context can it be properly understood and a conservative alternative to Towards Fairness’s progressive approach be developed.

White Australia policy and social cohesion

The White Australia policy underpinned one of the first statutes passed by the Australian Parliament: the Immigration Restriction Act 1901. It was repealed by the Immigration Act 1958, however, the policy’s broader legacy remained until the passage of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975.

In The End of Certainty, Paul Kelly identifies the White Australia policy as one of five policies that together formed Alfred Deakin’s Australian Settlement.[57] The Immigration Restriction Act may have determined immigration policy, but Kelly explains that the White Australia policy was more than that: “it was a creed which became the essence of Australian nationalism and, more importantly, the basis of national unity”.[58] This immigration policy was complemented by economic policies (protectionism and industrial arbitration), social policy (state paternalism), and defence and foreign policies (imperial benevolence) that enjoyed bipartisan political support for the first 80 years of the Commonwealth. Kelly’s history of the 1980s is the story of the undoing of this Australian Settlement.

Two years before Kelly published The End of Certainty, Gerard Henderson advanced an alternative analysis in his Australian Answers.[59] He argues that the White Australia policy was one of three policies that together form the Federation Trifecta. According to Henderson, the White Australia policy needs to be seen primarily as part of a broader economic policy that included protectionism and industrial arbitration. The economic climate of Australia could be artificially sustained by regulating wages through industrial arbitration, protecting local industry from foreign competition, and restricting cheap foreign workers from the labour market.

Writing in 1930, Sir Keith Hancock understood the White Australia policy to have a broader role: “The policy of White Australia is the indispensable condition of every other Australian policy”.[60] Yes, there were economic justifications, as “an influx of the labouring classes of Asia would inevitably disorganise Australia’s economic and political life”, but he recognised something more fundamental was at stake. Racial homogeneity was the basis for the fledging country’s social cohesion.[61]

To say that Australia was White in 1930 was not simply to state a fact about its ethnic composition. It was to express a positive attitude towards this: it was to affirm that White Australia was both ethnically homogeneous and socially cohesive. The latter was not only desirable, but a remarkable achievement for a country that was only 30 years old.

What this reveals is that, at its most fundamental, the White Australia policy should be understood as a policy about social cohesion. As such, the end of the White Australia policy marks the beginning of a new policy approach to social cohesion. It is the beginning of an era in which it was understood that social cohesion no longer depends on sameness. For the next 50 years, public policy for social cohesion sought to achieve unity through a commitment to diversity rather than sameness. Kurti’s essay seeks to demonstrate that the commitment to diversity in Towards Fairness cannot be sustained in a liberal democratic state.

Social cohesion

The 2023 Edelman Trust indicated that trust in institutions was at an all-time low in Australia, with only 48% of people expressing trust.[62] It also revealed that polarisation, the process through which social opinion becomes not only divided, but entrenched with an us-and-them mentality, is increasing to the point that the country is currently straddling the boundary between being ‘moderately polarised’ and ‘in danger of severe polarisation’.

Australian politicians warn that this increasing polarisation is having a pernicious effect on social cohesion.[63] Keith Wolahan, federal Member for Menzies, has spoken of the way “information silos” are resulting in “fragmentation” and a tendency “to exaggerate our own virtue and see the other as a cartoon villain.”[64] James Paterson, a Senator for Victoria, has warned that foreign powers, including companies controlled by the Chinese Communist Party, may take advantage of this tendency “to sow division, undermine social cohesion, erode national unity and suppress inconvenient narratives”.[65] Andrew Hastie, the federal Member for Canning, has also warned that the collapse of the social and moral consensus in Australia over the last 30 years can be used to advantage by authoritarian regimes such as Russia, China, and Iran: “the challenge for us is if we’re divided as countries, it’s very hard to meet those authoritarian threats” because, he argues, when there is so little social cohesion, “it’s very hard to come up with grand strategy” for combatting foreign threats.[66]

This much is to say that there is an acknowledged problem with social cohesion in contemporary Australia, but what exactly is meant by social cohesion? The Scanlon Foundation Research Institute was formed to conduct and lead research on social cohesion, and has earned a reputation as a leader in the field. The institute admits, however, that “there is no standalone definition when using the term social cohesion”.[67] It traces the term back to Émile Durkheim’s 1897 study, Suicide, in which he identifies two aspects: the absence of latent social conflict and the presence of strong social bonds. After reviewing a range of approaches, the institute adopts as a standard the definition proposed by Dick Stanley, namely that social cohesion is “the willingness of members of society to cooperate with each other in order to survive and prosper”.

What we now see is that to understand the White Australia policy as a means of achieving social cohesion is to understand it as a means of avoiding latent social conflict and of maintaining strong social bonds so that members of the society are willing to cooperate with each other in order to survive and prosper.

Whereas sameness was the basis for cooperating for survival and prosperity in the White Australia era, something else would have to serve this function as the society became more heterogeneous. It has been proposed that multiculturalism might play this role, however, Kurti has demonstrated why programmatic multiculturalism is not fit for purpose. However, this is where the challenge remains: how do we increase social cohesion in an increasingly diverse society?

Kurti on multiculturalism

There are three broad observations that I would make about Kurti’s approach to multiculturalism. The first concerns his approach to social cohesion; the second, his approach to the state; and, the third, his understanding of non-programmatic multiculturalism.

Social cohesion, unity, and sameness

Kurti takes multiculturalism to be a commitment to diversity and that diversity is the opposite of unity. As such, it appears to be incompatible with social cohesion. The White Australia policy was an approach to social cohesion that depended upon sameness. If the pursuit of social cohesion depends upon sameness, then multiculturalism is incompatible with a commitment to diversity. The post-White Australia approach to social cohesion has been about the idea that social cohesion does not necessarily depend upon sameness but that there might be a way of achieving social cohesion even within a diverse society. Multicultural advocates have gone so far as to claim that social cohesion can be achieved not only in spite of diversity but indeed in virtue of diversity.

Diversity alone is not going to achieve social cohesion, and Kurti is right to draw attention to the mistaken commitments to programmatic multiculturalism, which have resulted in the Towards Fairness recommendations that would enshrine identity politics within public institutions. What is apparent, however, is that, in a society that is increasingly diverse, social cohesion is not going to be derived from sameness.

Kurti’s conflation of social cohesion with unity is unhelpful here. In part, one senses, he equates unity with shared values. The Scanlon Institute connects social cohesion with lack of social conflict, presence of strong social bonds, and the willingness of members of a society to cooperate with each other in order to survive and prosper. Of course, shared values are a very effective way of reducing social conflict, creating social bonds, and inspiring people to cooperate for their survival and prosperity. There will be fewer shared values in a more diverse society, however, and so it might prove necessary to open our minds to new possibilities for social cohesion. A preoccupation with unity, sameness, and shared values might distract us from other possibilities.

The liberal democratic state and multicultural society

Kurti is broadly correct in his approach to the liberal democratic state. He is also correct in warning that programmatic multiculturalism is incompatible with the liberal democratic state. The mistake of programmatic multiculturalism is that it seeks to change the relationship between the state and the individual citizen.

This mistake would not have happened if advocates for multiculturalism had recognised that multiculturalism is a claim about the nature of Australian society, not a claim about the state. If they had appreciated that distinction, they would have realised that a multicultural society advances through cultural or civil society institutions that promote cultural diversity in society, not through public institutions that change the legal relationship between the state and the individual citizen.[68]

Kurti has a tendency to err in the opposite direction. If liberal democracy is a claim about the relationship between the individual citizen and the state, then he should be careful not to let it restrict our understanding of the relationship between people and the society to which they belong. He appears to move from discussing “the fullest involvement of the liberal state in the lives of its citizens” to warning that “a liberal society must protect the freedom of the individual to choose not to belong to a group or to be bound by its cultural, moral or religious norms and expectations”.

It is the role of the state to protect the freedom of the individual through public institutions, primarily the law courts. It is primarily a matter for society – not the state – to provide conditions that avoid latent social conflict and maintain strong social bonds, so that members of the society are willing to cooperate with each other in order to survive and prosper.

To say that the state should not encroach on the domain of society is to understand why programmatic multiculturalism is misguided: the state is the domain of liberal democracy, not the domain of multiculturalism. The flipside, however, is that society is not necessarily the domain – or at least not the primary domain – of liberal democracy. If multiculturalism is a claim about the society rather than a claim about the state, then there is no reason why a multicultural society is incompatible with a liberal democratic state.

Social cohesion is fundamentally a claim about the society, not a claim about the state. The White Australia era sought to maintain social cohesion in society through sameness. The multicultural era sought to maintain social cohesion through diversity. A society that is increasingly less homogeneous will need to find a way of achieving social cohesion despite the increasingly divergent values of people within that society. The challenge of promoting social cohesion in contemporary Australia is a challenge for its multicultural society, not for its liberal-democratic state. As such, it is a challenge that must be met using the resources of the society, not the resources of the state.

Multiculturalism as a fact and multiculturalism as a value

To be sure, Kurti is not opposed to the idea of multiculturalism per se – his target is programmatic multiculturalism. The problems, he maintains, started when descriptive multiculturalism gave way to programmatic multiculturalism. Descriptive multiculturalism “simply refers to cultural diversity in a society in which different cultural, social and religious communities coexist”. To say that a society is multicultural in this sense is to make a purely descriptive statement about it.

Kurti does not find such descriptive claims problematic. He contrasts them with claims about programmatic multiculturalism which are problematic. The problems involve the way the descriptive claims are used ultimately to advance identity politics.

There is another distinction that might be made, but which Kurti does not make. In Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy, Bernard Williams introduces a distinction between concepts that are thin and concepts that are thick.[69] A thin concept is one that is either descriptive or evaluative.[70] A thick concept is one that fuses evaluative and descriptive components.[71] These are important for Williams because he thinks that most of the concepts that we use in our ordinary ethical lives are thick ethical concepts.

When we talk about multiculturalism in the post-White Australia era, we are talking about it as a thick concept. It is not merely descriptive. White Australia was a thick concept that not only described Australia’s ethnic composition, but expressed something desirable about Australian society, namely the social cohesiveness that attended ethnic homogeneity. To understand multiculturalism as a policy response to White Australia is to see it as a thick concept that provides an alternative to another thick concept. The descriptive component has changed, in that it captures the ethnic diversity of Australia, but it continues to retain a positive evaluation, namely that the culturally diverse country is socially cohesive, and that this too is an achievement – albeit for different reasons.

When Kurti treats multiculturalism in its earliest incarnation as a purely descriptive concept, he fails to articulate the sense in which it could serve as a replacement for the White Australia policy. The problem is more serious than that, however. If we run with multiculturalism as a purely descriptive concept, then it seems that programmatic multiculturalism is necessary as a response to White Australia – or at least it is the only option currently on the table.

Kurti has shown us why we should not embrace programmatic multiculturalism, but he needs to revise his concept of descriptive multiculturalism. He needs to demonstrate that it is possible for non-programmatic multiculturalism to be something more than a descriptive concept. Non-programmatic multiculturalism can carry a positive evaluation about Australia’s ethnic diversity. In this way, it can serve as a basis for a socially cohesive society without slipping into identity politics.

Toryism and belonging

Conservatives are right to reject the Towards Fairness recommendations. If the identity politics that informs them is not the path to social cohesion, then what is the conservative approach to achieving social cohesion? Kurti’s achievement is to focus attention on the need for a conservative policy response to this challenge. Perhaps, that response depends upon whether conservatives subscribe to Toryism or American Republicanism. Kurti’s approach suggests a commitment to the latter, but maybe there is a distinctly Tory response.

The Tory solution might lie in the repudiation of identity groups and the conservative alternatives. Tories might distinguish between the progressive idea of identifying and the more conservative idea of belonging. They might also distinguish between groups with which people can identify, and the small platoons to which they belong. In one of the most famous passages in Reflections on the Revolution in France, Edmund Burke writes:[72]

To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections. It is the first link in the series by which we proceed towards a love to our country and to mankind.

The idea of little platoons took on great significance in 20th-century conservative thought, notably through its use in Russell Kirk’s The Conservative Mind, and has continued to be a source of inspiration for contemporary thinkers such as Yuval Levin in The Great Debate, although James McElroy has warned that we need to keep in mind the difference between Burke’s use of the term and contemporary usage.[73]

The idea that we belong to small institutions, such as families, through which we are connected to larger institutions, such as countries, is an insight that could be used as a basis for creating social cohesion. These are institutions that we naturally belong to, as opposed to groups that we choose to identify with because of shared identity characteristics.

A liberal-democratic state in which people value the cultural diversity of their society might well see merit in trying to strengthen the small platoons to which its members belong, and the series of links through which these can instil a sense of belonging to one’s country as a means of achieving social cohesion. It might offer greater success than trying to focus on cultivating shared values. Strengthening such ties of belonging would anchor social cohesion in a shared sense of feeling at home in one’s society. Such an approach might find inspiration in Sir Roger Scruton oikophilia, the sense of love for one’s home.[74]

The small platoons to which people belong in contemporary Australia may well be different from those to which they belonged in an earlier era. That said, a public policy approach that acknowledges these contemporary small platoons as the building blocks of Australian society might then go a step further. It might affirm them as valuable features of Australian society through which we can maintain the strong social bonds that encourage those who belong to Australian society to cooperate with each other in order to survive and prosper. In doing so, a Tory policy of social cohesion that is both post-multicultural and post-White Australia might emerge.

A Cultural Free Market. Australia needs natural assimilation and negative social cohesion based on division of labour and market exchange

Jonathan Cole

Peter Kurti is concerned that the ‘compact’ that has underpinned the successful’ Australian model of multiculturalism — a “tolerance of diversity in Australia … bounded by a commitment to the spirit of Australian law and order” — is under threat from what he calls programmatic multiculturalism. Programmatic multiculturalism describes the program of government policy that promotes cultural diversity via ‘subsidy’ and ‘preferential treatment’. Programmatic multiculturalism shifts the onus of the compact from cultural diversity united around observance of shared ‘Australian norms’ to observance, indeed obeisance, to the new social norm of ‘diversity’ per se. This is to say that the diversity that is the by-product of a multicultural society in a descriptive sense has been transformed and elevated into something like a state ideology, i.e., something the state should promote, celebrate, expand and defend from any perceived threats, including dissent. Diversity is no longer a social fact to be navigated and negotiated within a paradigm that balances rights and duties, but the greater good to which all other social considerations, perspectives and interests must be subordinate.

Kurti is correct in identifying this significant shift in the understanding and function of the concept of multiculturalism in Australia, from social compact to state ideology (my language, not his), and is to be commended for drawing attention to its consequences. In this response, I argue that a solution to the concerns Kurti articulates regarding programmatic multiculturalism, which I share, is for the government to vacate the business of regulating culture altogether and rely instead on a free and self-governing market of cultural competition. I further contend that this solution will avoid a problem that I detect in Kurti’s defence of Australia’s historical multicultural compact. Finally, I will address the matter of social cohesion given this is the primary concern animating both Kurti’s criticism of programmatic multiculturalism and his defence of the older Australian multicultural compact.

The virtues of a free cultural market

My case for a free cultural market in Australia proceeds from one important presupposition that must be stated at the outset. Multiculturalism, in the descriptive rather than programmatic sense of the term, which is to say ethnic, linguistic, cultural and religious diversity, is, at this juncture in Australian history, a permanent and irreversible feature of Australian society. Were all migration to cease this day forward and into perpetuity, Australia would remain a highly diverse society. There is no turning back the clock on the social reality of multiculturalism. It is important to clarify this fundamental datum of Australian society as it highlights that all debate about social cohesion must assume and contend with the fact that the society doing the cohering (or failing to) is marked by a high degree of diversity, and therefore, by nature, pluralism.

If programmatic multiculturalism is a problem, indeed a threat to social cohesion, as Kurti contends, for its potential to encourage ‘cultural separatism’ and ‘fan hostility between different sections of the community’, then the obvious remedy is to abolish it altogether. By ‘abolish’, I mean de-institutionalise and de-fund the multicultural architecture, infrastructure and (government-funded) industry. The purpose, and if not the purpose, then the effect, of the government’s intervention (via programmatic multiculturalism) in matters of culture and diversity, is to subsidise languages, customs and religious beliefs and practices that otherwise might struggle to survive and thrive in a genuinely free market of culture. This type of government intervention makes sense only if we accept the assumption underpinning programmatic multiculturalism that diversity is the social greater good to be realised, maintained, expanded and defended as a matter of government policy. While I think Kurti’s concerns about cultural separation and communal conflict resulting from programmatic multiculturalism are overstated, although not entirely unfounded, I share his antipathy towards this government program, albeit for different reasons.

My primary criticism of programmatic multiculturalism is that it constitutes an entirely unnecessary government intervention into cultural matters that should remain the preserve of individual choice and voluntary association. In that regard, programmatic multiculturalism entails yet another instance of the growing reach and scope of the state (intrusion) into the natural operations of social life. The real offence of programmatic multiculturalism is the unhealthy statist view of social order that it presupposes and expresses, namely, that the state’s role extends to governing, shaping, reforming, directing and programming the social relations of its citizens, including ‘managing’ their diversity. Such a logic is born of an infantilising fear or anxiety about the inherent untrustworthiness of adult human beings to treat each other in civilised ways absent a benign government incentivising and coercing them towards decency.

Abolishing programmatic multiculturalism will not affect multiculturalism as a descriptive fact of Australian social reality, in which case politicians, academics, journalists and common citizens will be able to talk honestly about an Australian multicultural reality, and celebrate its perceived virtues and successes. Moreover, citizens and residents will be free to retain and maintain their languages, customs and religious beliefs and practices (subject to the limiting factor of Australian criminal and anti-discrimination law) and to pass them on to their children. It just means that they will not receive government financial support, and hence taxpayer subsidies, to do so. Individuals and communities will shoulder the responsibility of finding the time, energy and resources to maintain and pass down their cultural traditions on the back of their own efforts and initiative. Migrating to a foreign land and culture does not come with a right to recreate the migrant’s original cultural world for the sake of convenience at the expense of taxpayers who do not belong to that culture.

In a genuinely (classical) liberal society, individuals will even enjoy the freedom to adhere to some version of a multiculturalist ideology. However, in the absence of any government funding, positions and institutions to work in, capture, lobby or fleece, it will be much harder for those who embrace multiculturalism as an ideology to impose it on others. They will have to rely on persuasion and the strength of their arguments. Meanwhile, people like Kurti who value traditional Australian customs, norms, laws and institutions, will be free to defend and proselytise their virtues, while competing with their ideological foes without the government tipping the scales in either’s favour.

In a genuinely free cultural market, cultural competition will ensue, because this is the natural state of affairs in cultural life, especially in the context of cultural contact and diversity. The notion of free cultural competition might make conservatives nervous. But the proper antidote to programmatic multiculturalism is not programmatic state-funded, state-supported or state-imposed conservatism. Conservatives tend to be cultural protectionists. They want metaphorical government tariffs, excises, duties and other subsidies and regulations to protect the domestic market of traditional Australia culture from encroachment by other cultures and traditions. Like all protected industries, they do not want to compete in an open market, for fear that consumers will choose other products and services, leading ultimately to bankruptcy.

Cultural assimilation has pejorative connotations in 21st-century Australia, thanks to the worldview of programmatic multiculturalism and a history of contentious attempts to programmatically assimilate Australia’s first inhabitants. However, the truth is that cultural assimilation is a natural process that accompanies migration. It has been so for millennia and remains the case everywhere on the globe, including in Australia, despite the best efforts of programmatic multiculturalism to prevent or forestall this natural human tendency. It is not uncommon for the children of migrants to abandon the customs, beliefs and practices of their parents as they assimilate to Australian society, or at the very least to adapt them to the new cultural environment in which they grow up. A genuinely free market in culture, given the market share of English, the monopoly of Australian law, and the inclusive power of national cultural products like sport, would likely facilitate the natural process of assimilation, particularly in the absence of any hindrance by a state-funded and state-supported programmatic multiculturalism. It would also raise the costs of cultural separation, thus promoting greater social cohesion.

In sum, there is simply no need for the government to regulate ‘diversity’, whether through its promotion, defence, subsidy or any other form of support. Language, culture, custom and religion should remain matters of personal choice and voluntary association, subject to the limiting factor of Australian criminal and anti-discrimination law. A genuinely free market of culture in Australia would likely lead to more and faster assimilation, because assimilation is a natural process that accompanies migration, and because English and Australian institutions and laws enjoy enormous market share (monopoly in the case of Australian law). Individuals will remain completely free to hold onto their patrimonial or ancestral languages, customs, traditions and faiths if they wish to. However, they will need to bear the costs (financial and social) of doing so themselves.

The disappearance of a hegemonic Australian culture and its consequences

Kurti’s antidote to the rise and dominance of programmatic multiculturalism appears to be the restoration, or revitalisation, of the original compact drawn up in the wake of post-World War II mass migration (or a version thereof). Kurti refers several times to Australian norms, laws and institutions as the ballast for social cohesion amid cultural diversity. This compact, however, relied on a hegemonic Australian culture that no longer exists, and is no longer feasible.

Great cultural diversity existed on the Australian continent prior to the arrival of European settlers, who in turn added their own diversity. The ships that carried Australia’s first European settlers included the speakers of different languages (English and Gaelic), different ethnicities (English, Irish, Welsh, Scottish and African[75]) and different faiths (Church of England, Catholic, Presbyterian and Judaism). Not long after, German settlers arrived in South Australia and Chinese migrants arrived in Victoria and NSW during the gold rush. The Australian continent, in its pre-settler, colonial and Commonwealth manifestations, has always been multicultural. It is the scope and depth of diversity that has changed more recently with mass migration.