Introduction

Although remote Indigenous communities[1] have been a major focus of policymakers for over half a century, particularly in recent decades, there is a clear lack of evidence of the results of those generously-funded policy interventions.

In fact, there seems to be a downward spiral. This is evident from the Closing the Gap data; and the other gap — the one between Indigenous people who are educated and live in the cities and those in remote communities who are not.[2] It’s evident from the woeful school attendance by Indigenous children living in remote and many regional communities. And it’s evident from the statistics on violence and crime and the daily media reports as all of this spills over into regional centres like Alice Springs.

The 2023 Voice referendum sent a clear message to governments. Australians do not want divisive and ideology-driven solutions or race-based policies. Australians want real improvements in Indigenous lives and policies directed towards need that deliver outcomes. Indigenous Australians want this too.

The politicians, the corporates and the rest of the big end of town who supported a constitutional Voice listened to the noise: the noise of Indigenous people in academia, the public service and government funded organisations, who already direct policy and speak to governments and who sought entrenched, privileged rights to continue their failed advocacy.

Politicians should listen to the silence. The silence of Indigenous Australians who refused to engage in the Voice referendum at all. Available booth data from remote Indigenous communities in Western Australia, Northern Territory and Queensland indicate over 60% of Indigenous voters in those communities abstained from voting in the Voice referendum; with the Yes vote as a percentage of all eligible voters in those communities even lower than the Australian population at large.[3]

The silence of over 90% of Aboriginal people in South Australia who chose not to vote in elections for the South Australian First Nations Voice; and the 93% of Victorian Aboriginals who did not turn out to vote for elections for the Victorian First People’s Assembly. With their silence, Indigenous Australians have sent a clear message.

It’s time to stop these voices and committees. Stop wasting money on talk-fests and largesse for the usual suspects who already sit at the table. It’s the same old, same old, since the Whitlam years. And it hasn’t improved Indigenous lives.

Real economic solutions — and the environment to allow them — are needed to bring real change, to drive Indigenous participation in the economy, to provide opportunities to earn a decent income, to deliver the freedom to make economic choices and to incentivise economic activity.

The problems remote Indigenous communities face are interrelated and form a vicious circle. They start with the fundamental barrier that traditional lands are collectively owned and controlled; closed communities within which individual property ownership is not permitted, effectively practising a form of government sponsored socialism. This does not provide the key building block for a real economy: private land ownership. This stifles key avenues of economic participation, including home ownership and also opening and running small businesses. Communities have almost a complete absence of commerce.

This, in turn, is at the heart of low school attendance and lower educational attainment, which contribute to a lack of skilled labour force in these communities and stifle business activity and employment. Lack of employment opportunities allows young people to fall through the cracks of the system, and after finishing school they end up at best unemployed and on welfare, or at worst engaging in criminal activity.

All of this contributes to social instability, including high crime rates and other dysfunction —such as alcohol and substance abuse — and in many cases a breakdown of the rule of law. Social instability discourages business creation. Lack of private property ownership, a skilled labour force and social stability are all factors that repel investment capital and business lending.

Market economy and democracy, the rule of supply and demand as well as the rule of law are the blueprint for economic prosperity. It has been proven successful for many countries and communities. There is no reason why applying the core principles of economics should not work for Indigenous communities as well as it has served Australia as a whole.

This paper builds on the foundations of democratic free market economy participation and addresses the four pillars that need to be addressed to pave the way forward to include the Indigenous communities in Australia-wide economic prosperity.

The roadmap to closing the gap is through real economic solutions under the four pillars:

- Economic Participation

- Education

- Safe Communities

- Accountability

This paper makes recommendations based on economic incentives and real solutions with circuit breakers via the justice system, welfare system and community-based protections. This is coupled with proposed fundamental changes to the framework that has underpinned Indigenous policy and rights for decades, to achieve accountability, reform of land rights and land trusts, efficiency and economic participation.

Pillar 1: Economic Participation

Business ownership

Small and medium business ownership is critical for economic prosperity. It provides a source of independence, income, and employment opportunities for local communities.

It is difficult to precisely quantify the gap in the business creation and ownership of Indigenous people compared to other Australians, because of the lack of reliable data. There is no nationwide registry of Indigenous business ownership, despite multiple organisations tracking Indigenous-owned enterprises — such as Supply Nation, the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations, Indigenous Chambers of Commerce (e.g. Kinaway) and the Industry Capability Network Limited (ICNL). Registration is voluntary, and some Indigenous Australians may be reluctant to register or not see the need.

One of the most precise and detailed studies is a sample of approximately 3,600 active Indigenous businesses using I-BLADE; this is an integrated data set matching information from Indigenous business registries with the Australian Bureau of Statistics Business Longitudinal Analysis Data Environment (BLADE). Under the study, at least 50% Indigenous ownership was the criteria for an Indigenous business. While the report notes that it still underestimates the number of Indigenous businesses, it provides an important snapshot and the critical starting point for understanding the Indigenous economic landscape.[4]

The report found that between 2006 and 2018 there was a 74% increase in the number of Indigenous businesses, 115% growth in revenue and the creation of more than 22,000 jobs. This indicates the capacity of the Indigenous business sector to drive economic prosperity for Indigenous people, with Indigenous businesses having larger than an average Australian business in average revenue — $1.6 million versus $400,000 and employing on average 7 times more workers.[5]

Indigenous businesses were found to be especially critical in driving economic prosperity in remote areas. The report found 58% of Indigenous businesses were located outside major cities — 32% in regional areas and 26% in remote areas. This compares with the non-Indigenous sector where 74% of businesses are in major cities. The 26% of Indigenous businesses in remote areas provided 37% of all jobs or 14,030 jobs in 2018.[6] However, the data also showed a downward trend for the number of Indigenous businesses in remote areas, with a corresponding increase in major cities.

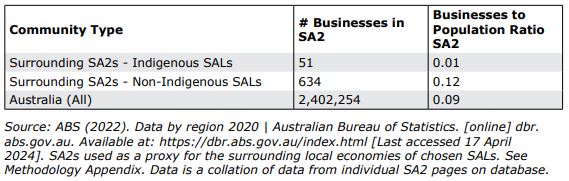

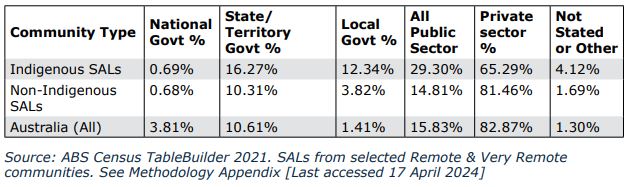

A 2023 CIS research report used the Australian Bureau of Statistics data on Statistical Area Level 2 (SALs) areas; being areas with a mean population of approximately 4,200 people. The report considered data on the SA2s that surround selected remote Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities as a proxy for the local economy.[7]

The median number of businesses in the remote non-Indigenous SA2s was 0.12 per person (higher than for all Australia) compared to only 0.01 businesses per person in the remote Indigenous SA2s. This demonstrates a fundamental difference in the economies of remote Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities that cannot be blamed on remoteness or population size. The report concluded:

“Significantly, [remote] Indigenous communities trail well behind [remote non-Indigenous communities] in virtually every metric. Levels of education, the foundation for economic participation, are poor. Engagement in the economy is low, with nearly two thirds of working aged people choosing to not even attempt to find work and many more reliant on welfare. Of the jobs that do exist, a significant proportion are reliant on the public sector propping up the employment market – never a good sign for an economy. Business ownership – the most important foundation of an economy – is almost non-existent. Only a small number of businesses are running despite the existence of populations that can support significantly higher levels of economic activity. While this can somewhat be put down to the greater number of Indigenous communities in the ‘Very Remote’ category of this analysis, the data on non-Indigenous communities suggest that Indigenous communities could have at least a small functioning economy — as opposed to their virtually non-existent economies at present.

“Indeed, the high-level analysis of remote non-Indigenous SALs gives us a powerful insight into what the economies of Indigenous communities could look like.”

The data point towards substantial economic potential being trapped in remote Indigenous communities and restricted by structural barriers which, in turn, generate socio-economic barriers of disadvantage and lack of opportunities. Unleashing this economic drive can lead to economic growth, financial independence and economic prosperity — and erase the socio-economic gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, leading to equal outcomes.

But we must address these structural barriers. The key one is land tenure. There is no private property ownership on traditional lands. Land is collectively owned by centralised Indigenous bodies. Likewise, royalties and other payments by mining companies, governments and others for use of, or loss of, land are held collectively by organisations or in land trusts. Yet, despite owning vast amounts of land and billions in land payments, Indigenous people in remote communities live in abject poverty. They cannot own their own home and are dependent on centralised, community-controlled organisations for housing, income and other daily needs.

The inability of individuals to own private title on these lands sits at the core of the lack of economic participation and the economic dysfunction in many remote Indigenous communities. Home ownership is a critical factor in economic independence and wealth creation for many Australians. But this is denied to Indigenous people living on these lands. Likewise, it means business creation is virtually impossible.

In communities on traditional lands, there is a complete absence of individual, private title. But this model persists even in towns like Alice Springs where private property ownership is available for everyone except for residents of the Aboriginal town camps, which are collectively owned and controlled by Aboriginal controlled ‘councils’ that run some of the most appalling and derelict housing and communities in Australia.

Individual private property ownership is the pillar of every free, liberal democracy and the foundation of economic prosperity across the world — in every place and among every people. Indigenous Australians should have it, too.

Land reform does not require some kind of specially-tailored solution for Indigenous people. There are established models of land ownership and land reform that will work. All land ownership in the Australian Capital Territory is leasehold via 99 year leases. People living on traditional lands could have effective private ownership via leasehold, without voiding the ultimate ownership of the relevant traditional owner body. Strata title provides another model for home ownership within a broader title where there is also shared ownership of common areas.

A concern sometimes raised in discussions about private land ownership on traditional lands is whether this will allow people who are not traditional owners to purchase property in these communities and live there. What this ignores is that most of these communities already have people living in them on a long-term basis who are not traditional owners or even Indigenous. These include people from outside the community who work in the community as teachers, nurses or other service providers, and spouses and domestic partners of locals who have moved with them into the community.

What would be wrong with these people putting down roots in the community and buying their own home — or renting it from a local owner? That is how economies are built. And what would be wrong with an outsider investing to build housing in remote Indigenous communities? There is a chronic shortage of housing in many of these communities.

In March 2024, the federal and Northern Territory governments announced an agreement to spend $4 billion to build 2,700 houses in remote NT communities over 10 years to “halve overcrowding”. It is hard to understand why the federal and NT governments have to pay for housing on Aboriginal lands when there are billions in Aboriginal land trusts and other bodies; including from royalty payments and native title payments.[8] What is being done with that money? Why are those funds not being used to build housing? Or they could be used to support partnerships between governments and traditional owners to jointly fund housing, infrastructure and business creation on their own lands. Partnerships with private investors would also be possible if lands are opened up to private title.

Employment

Employment is one of the most significant enablers of financial security, the ability to be a functional member of the community and even overall well-being.[9] According to 2021 Census data, the unemployment rate of First Nations people was 12%, while the Australian overall rate was 5.1%. The proportion of employed Indigenous people is also lower: 55.7% versus 77.7%[10] for overall Australia — meaning a larger share is neither working nor looking for work (not in the labour force). Further, the proportion of unemployed people and people not in the labour force was higher in the remote and very remote communities.[11] At the same time, employment is linked to increased financial independence and community development for Indigenous people in particular.[12]

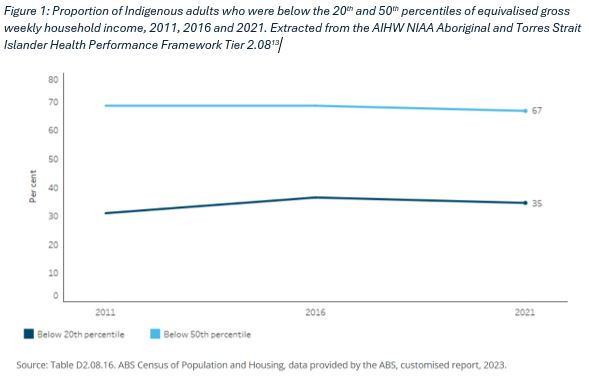

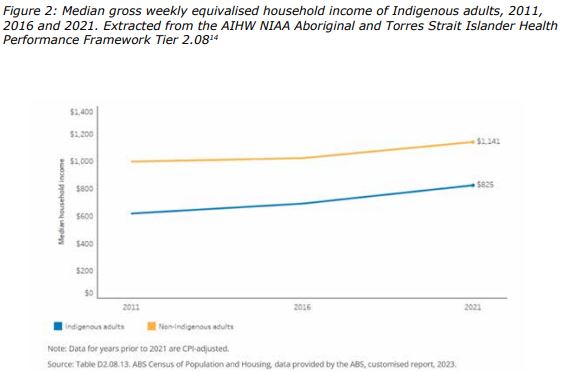

Unemployment is especially harmful to young people when coupled with disadvantage. Young people experiencing disadvantage are more likely to experience unemployment, especially long-term unemployment. Income data show Indigenous Australians are also more likely to live in low-income households (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2021).

Unemployment is also intergenerationally transmitted and is more socially accepted when there is a higher proportion of jobless individuals in the community. Being surrounded by other unemployed family and community members increases the risk of staying unemployed even further. That vicious cycle is often observed in remote Indigenous communities and needs to be interrupted.

Barriers to labour force participation and employment include low school attendance and low rate of tertiary education uptake, crime and safety issues and limited job opportunities in the area. All of them are interrelated and exacerbate one another, but all fall within the economic sphere.

Another dimension of economic participation specific to youth is the so-called ‘not in education, employment or training’ (NEET), which refers to a young person who is neither engaged with any education or training nor in paid employment.[15] 45% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people were classified as NEET, compared to 14% of non-Indigenous young people[16] in 2016, with a slight improvement in 2021 Census data seeing the NEET rate decrease to 42%.[17]

The gap in employment level disappears with higher levels of education. There is virtually no employment gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians who have education at the Certificate III level or above and none at the highest levels of education. Differences in educational attainment account for almost 40 percentage points of the difference in employment outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.[18]

This points to the conclusion that a race-based divisive narrative to solving the socio-economic disadvantage problem is not the right way forward.[19]

Pillar 2: Education

Education inequality is another pressing issue in Indigenous communities. It creates barriers to accessing employment opportunities and better-paid jobs, and generates local shortages of skilled workers that stifle business growth. It is especially damaging for youth, as education is the key ingredient in successful transitioning into employment and reducing the risk of long-term joblessness. The education and literacy indicators are consistently lower across the range of factors, including school attendance, completion and tertiary education uptake.

Some years ago I spent time in Aurukun, a former mission that in recent decades has been an archetype for the problems of social dysfunction in remote Indigenous communities. I was shown a class photo of the last children to attend the mission school before the missionaries departed and was told that this was the last generation of children in Aurukun who learnt to read. Children there received a better education under the missions than after the 1967 Referendum. Think about that.

Individual school attendance is key

School attendance has been consistently lower among Indigenous children compared to the national average. The latest data by the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) reveals both a consistent gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students and a lack of improvement in recent years in school attendance.[20] The attendance rates from 2015 to 2023 fell from 83.7% to 77.4% for Indigenous children. Further, the gap in school attendance between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children over Years 1-10 is 12.1%. The gap is larger in more senior school years: for Year 10, the gap balloons to 18.9% for Indigenous students overall. In the NT, school attendance in Year 10 for Indigenous children is only 50.1% compared to 85.3% for non-Indigenous students.

We know that to get an effective education, a child must attend school 90% of the time. If a child frequently misses more than half a day of school a week (attendance below 90%), their education is considered at risk. If they miss one day of school every week (attendance below 80%), their education is significantly diminished.[21]

A child who attends a poorly-performing school 90% of the time will have a more effective education than one attending a good school less than 90% of the time. And a child who attends any school less than 80% of the time does not receive an effective education at all.

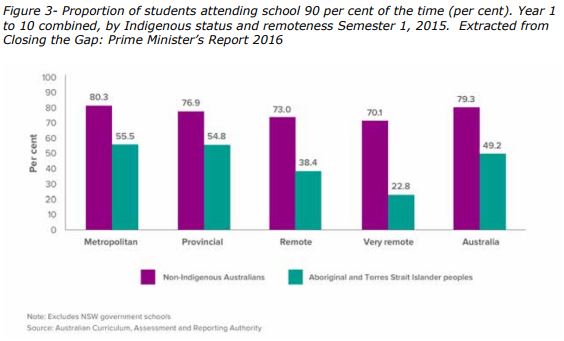

One of the problems with school attendance data as historically collected for Closing the Gap reports is that the data are aggregated, not individualised. An aggregate attendance rate of 70% could mean half the students attend 90% of the time and half attend 50% of the time, or that all students attend 70% of the time. In the first scenario, half of the students are getting an effective education whereas in the second scenario, none are.

When the Abbott government sought to report on individualised attendance data in the Closing the Gap reports, state and territory governments refused to provide it.[22] Most were later persuaded to do so by the 2016 Closing the Gap report, other than New South Wales which continued to refuse.[23] Looking at the 2016 Closing the Gap individualised school attendance data demonstrates why states and territories don’t like disclosing it. It shows they’re not doing their job.

The aggregated school attendance data in the 2016 Closing the Gap report showed a 10-point gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous school attendance. Individualised data told a far worse story. Only 49.2% of Indigenous students met the critical 90% threshold, compared with 79.3% of non-Indigenous students — a 30 percentage point gap. In very remote areas there was a 47 percentage point gap (See Figure 3).[24]

During the few years individualised data was reported in the Closing the Gap reports, we learned that half of all Indigenous children are not receiving an effective education at all because they aren’t attending enough school.

School attendance underpins everything else

In 2020, the Coalition of the Peaks and all Australian governments implemented a new set of targets via the National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the 2020 Agreement) which dispensed with the simple school attendance targets (individualised or aggregate) altogether.[25]

It does include targets for Year 12 attainment and tertiary education:

- Target 5: “By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (age 20-24) attaining year 12 or equivalent qualification to 96%.”

- Target 6: “By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 25-34 years who have completed a tertiary qualification (Certificate III and above) to 7%.”

However, no child will genuinely attain those achievements without an effective education. And an effective education requires a child to attend school 90% of the time from the beginning — which is not even being measured. Further, the data show these targets are not at all on track to being achieved.

Census data in 2021 revealed 68% of Indigenous Australians aged 20-24 completed year 12 or equivalent.[26] This is well below the national average of 89.9% and a far distance from the 2031 Closing the Gap target of 96%.

The gap in tertiary education between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians is even wider and increases with remoteness. Based on 2021 Census data, the Productivity Commission’s dashboard tracking Target 6 calculated 47% of Indigenous Australians aged 25-34 have achieved AQF of Certificate III or above, compared to 75.9% of non-Indigenous Australians. But only 19% of Indigenous people in the NT have tertiary qualifications. As noted in the section on pillar 2, there is a direct correlation between employment and level of educational attainment: the lower the level of education attained, the less likely people will be employed, and participation in full-time work increases with every additional completed year of schooling completed.[27]

The role of school attendance for outcomes later in life cannot be underestimated. High rates of missing school are shown to be linked with poor academic performance,[28] increased risk of dropping out of school[29] and subsequently lower chances of getting a tertiary degree. The widening gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous attendance towards the senior school years leads to lower levels of school completion and, in turn, employment.

In the long term, school absenteeism increases the risk of unemployment, drug and alcohol use and juvenile delinquency.[30] All those adverse consequences are observed in remote Indigenous communities and other disadvantaged Indigenous populations and discussed further in the fourth pillar of this paper.

Finally, we need to move away from the ideological battles over private vs public school, boarding schools and special Indigenous schools. Indigenous children in remote communities need access to good schooling, every day. Government schools are not performing for Indigenous children. Yet in my roles as Chair of the Prime Minister’s Indigenous Advisory Council and later dealing with the NIAA in advocating for Indigenous education organisations, I have experienced, first-hand, departments actively working to defund boarding school programs. If Indigenous children and their parents want private boarding school education, bureaucrats and ideologues should enable that, not stand in their way.

State and territory governments have failed Indigenous children

The state and territory governments’ resistance to providing individualised school attendance data under the previous Closing the Gap targets is a symptom of a broader lack of accountability by those governments for Indigenous people in education and beyond.

Under the Australian Constitution, state and territory governments are responsible for education as well as health, housing and most infrastructure. Indigenous Australians are Australian citizens under the Constitution, like every other Australian. State and territory governments are responsible for ensuring all children have access to adequately-resourced schooling and that they attend those schools. Clearly governments are not meeting their responsibilities for Indigenous children in remote communities. Where is the accountability for that? State and territory governments shirk their responsibilities for their most vulnerable citizens — Indigenous people living in remote communities — and then, when expected to meet their responsibilities, they put their hand out for more federal money.

I saw this as Chair of the Prime Minister’s Indigenous Council, particularly after the Abbott government introduced its Remote Schools Attendance Strategy in 2014, an initiative that prompted NT teachers to go on strike because more children were coming to school.[31]

In February last year, the Prime Minister and the NT Chief Minister met to discuss the growing crisis in Alice Springs. After the meeting, the Chief Minister called for more federal funding to meet the additional cost of remote service delivery saying, “The Commonwealth needs to step up and we need to see needs-based funding… The Northern Territory, based on GST formulas, and the cost we have of delivering services, it’s simply not fair”.[32]

Yet the NT government has been criticised over many years for diverting federal funding intended for remote communities to Darwin, described by The Australian as “greatest scandal in contemporary Aboriginal affairs”.[33] A Yothu Yindi Foundation submission to the Productivity Commission in 2017 identified that $522 million of GST revenue, allocated to the NT by the Commonwealth Grants Commission on account of its remote Aboriginal communities, was not in fact spent on services for Aboriginal people.[34] And the NT government’s policy of funding schools based on attendance rather than enrolments unsurprisingly results in less funding for schools in remote NT and also means those schools are not equipped to educate all children in those communities.[35]

And this year the federal and NT governments agreed to a new education funding agreement under which the Commonwealth committed to fund an additional $737.7 million for NT public schools over 2025-2029.[36]

They are let off time and time again.

Pillar 3: Safe communities

In March 2024, Alice Springs faced a severe youth crime crisis, leading to the unprecedented enforcement of a 6pm curfew. This crisis is not new but, in fact, in its second year.

The seeds of this crisis were sown in 2022 when alcohol bans were lifted in hundreds of town camps, and remote and homeland communities across the NT, while the federal government abolished cashless welfare. But the underlying cause of this crisis is more fundamental. In every community the world over, social breakdown, violence and drug and alcohol abuse go hand in hand with low school attendance, unemployment and chronic intergenerational welfare dependency. The only way to lift any group of people out of this malaise is economic participation. But economic participation, in turn, will not thrive in unsafe communities.

According to the 2021 Census, Alice Springs boasts a significant Indigenous community, constituting 20.6% of its population.[37] It also serves as a regional centre for many smaller remote and very remote Indigenous communities. This crisis is a symptom of a breakdown in economic inclusion and participation. It manifests in a vicious cycle of unemployment, low educational participation and restricted business opportunities. It is an example of why we should not ignore socio-economic indicators, and not underestimate the value of participation in the real economy.

Small and medium businesses stand as the foundation of economic prosperity, reliant upon the seamless function of the rule of law — including effective enforcement. Ensuring safety and a working legal system is the only government intervention SMEs require in a well-functioning free-market economy. Regrettably, crime rates are either escalating or remain stagnant across Indigenous and remote communities. For instance, hospital admissions post-assault were disproportionately higher for Indigenous people in 2021, an unsettling trend that persisted over a decade.[38]

The impact of crime — particularly property crime — on businesses is profound. In Alice Springs, residential burglaries have increased by 260%, and commercial break-ins by 164% since 2016.[39] This surge exacerbates the risk and cost of doing business. Studies show a clear negative correlation between crime rates and the performance of small and medium enterprises,[40] while crime also reduces business creation.[41]

The negative effect of crime is not limited to the higher cost of running the business but also leads to lower revenues and turnover. Safety concerns negatively affect the demand for local businesses’ goods and services.[42] The tourism and hospitality industries languish in areas with high crime rates.[43]

A scarcity of job opportunities often precipitates socio-economic hardship and a dependence on welfare support. When youth are neither at school nor at work, they are more likely to engage in criminal activities and drug and alcohol abuse.

Some schools in remote Indigenous communities have attendance as low as 30%,[44] while 42% of Indigenous young people are not in employment nor actively participating in the labour force. Indeed, 2022-23 data for young people aged 10-17 revealed Indigenous youth were about 23 times more likely to be under supervision, about 22 times more likely to be under community-based supervision, and about 28 times as likely to be in detention than non-Indigenous Australians.[45]

Communities that are beset by crime, drug and alcohol abuse, violence and other social dysfunction will have fewer businesses operating and generate fewer employment opportunities, leading to a downward spiral of shrinking economic participation and, in turn, a higher prospect of people within that community being involved in criminal activity.

These problems are rife in regional and remote Indigenous communities, which experience astronomically high rates of alcohol abuse, crime, and domestic violence at extremes that would not be tolerated anywhere else in Australia.[46]

Breaking this cycle is hard. Alcohol bans and cashless welfare are a start; bringing a community back from the brink and providing some relief to those who suffer most from dysfunctional behaviour, women and children. These measures will not solve the underlying causes but provide breathing space for more permanent improvements.

Ultimately, the root causes of these problems can only be solved by economic participation — children going to school, adults going to work and business creation. However, it is very hard to improve school attendance and employment in communities with deep social dysfunction.

We need to create a bridge between dysfunctional behaviour and economic participation by making employment and education a consequence of crime, essentially sentencing adult and juvenile offenders to work or education. For some offenders, this could be a condition of a non-custodial sentence. For others, a custodial sentence may be required to ensure the offender participates in employment or education, with the ‘custody’ being part of a program or facility where the offender is educated, trained and/or employed.

In particular, there’s little evidence that locking children up achieves rehabilitation. However, letting them go with a slap on the wrist does not rehabilitate them either. Instead, the powers of courts to impose custodial sentences could be used to impose education and/or training; such as in specialised boarding facilities or wilderness programs or work camps. This would require fundamental reforms to incarceration and detention systems but would change lives. And these initiatives should apply to all offenders, not just Indigenous offenders.

Pillar 4: Accountability

No policy, however well-designed or intended, will be effective without accountability. Without accountability, it is impossible to evaluate the effectiveness of the policy, properly track the expenditure, properly prioritise the policy in relation to other initiatives, continuously improve and adapt the policy or conduct a meaningful audit. The building blocks of accountability include:

- clarity on what the intended outcome of the policy is and why;

- targets based on outcomes (not activities) that are unambiguous, measurable and achievable, and a timeframe over which they will be assessed;

- transparent data to measure whether the targets are achieved;

- if targets aren’t achieved, an analysis of why, without fear or favour and without regard for vested interests; and

- consequences if the targets are not achieved, from minor consequences (such as changing the policy) to discontinuing the policy altogether.

When dealing with a series of policies all intended to address the same or related issues, policy actions need to be coordinated and consistent with each other and the overall objectives. The new Closing the Gap framework adopted in 2020 falls woefully short on accountability.

Closing the Gap, then and now

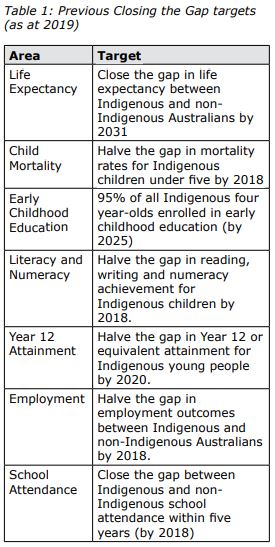

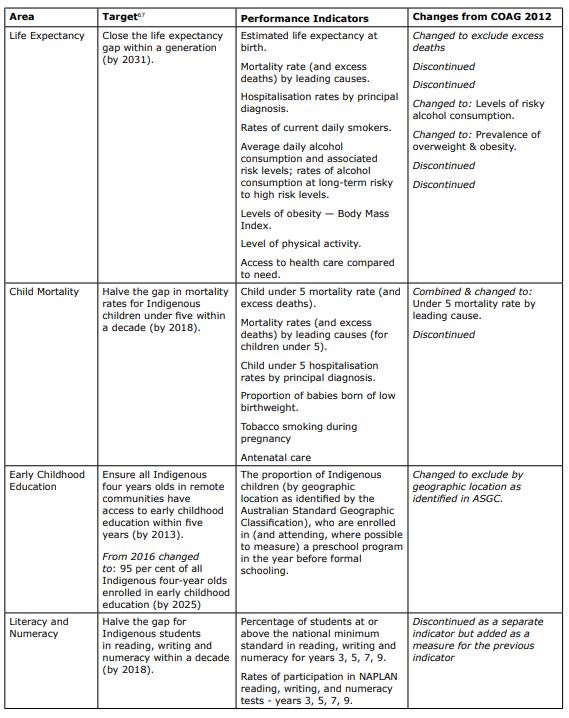

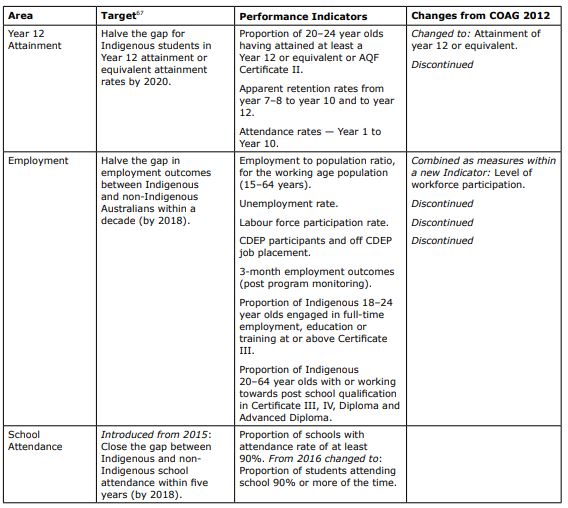

The Closing the Gap initiative was adopted in 2008 and was groundbreaking. For the first time, outcomes would be measured against unambiguous, quantitative targets — initially 6 targets, with school attendance added later by the Abbott government (see ). Each target had performance indicators by which they would be reported (refer to Appendix 1).

I always believed the biggest impact of the Closing the Gap initiative would not be to change Indigenous lives, but to lay bare the failure of decades of Indigenous policy. I hoped this would bring about a change in approach.

In 2017 I wrote:[47]

“People think Closing the Gap is an initiative to eliminate Aboriginal disadvantage. Actually it’s a scorecard of whether all the other programs and efforts are working. And it provides very little wriggle room to hide if they aren’t. Closing the Gap shines a huge spotlight on all the activities.

The governments signing on to Closing the Gap were like the Trojans opening the gates to a gift of a great wooden horse filled to the brim with Greek soldiers.

Because now, for everyone to see, at a big event every year to coincide with the opening of federal parliament … the annual Closing the Gap figures are released. And every year, for nine years now and counting, the figures show the gap isn’t closing.

All that money. All those programs. All those activities. Nothing to show for it. And in some cases the gap is getting bigger. Clearly, what governments have been doing for forty years hasn’t been working…

In 2018, the tenth Closing the Gap report will be released. That might be when the Greeks spill out of the Trojan horse. The ten-year anniversary, and the targets will be no closer to being achieved.”

As I anticipated, in 2018, Australian governments and Indigenous organisations and service providers were staring into the abyss of failure. But rather than change the approach, they changed the targets.

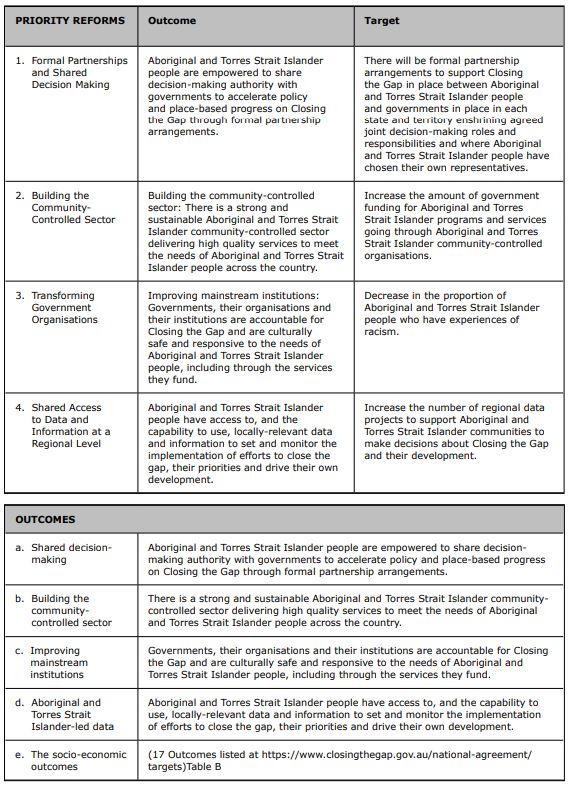

The 2020 Agreement replaced the previous 7 targets with:

- 4 priority reforms (each with its own outcome and target);

- 5 outcomes; with the fifth (socio-economic outcomes) being divided into a further 17 socio-economic outcomes and 19 socio-economic targets (the key measures of the outcomes), with each outcome having the following additional elements:

– indicators: supporting measures that provide greater understanding of and insight into how governments are tracking against the outcome and the target(s); each of which further divided into:

– drivers: measuring factors that significantly impact the progress made against the target(s); and

– contextual information: providing insight into the experiences of Indigenous people under the outcome;

– disaggregation: how reporting of the target(s) is further broken down and measured by reference to particular groups of Indigenous people

– data development: areas that are important for understanding the outcome but cannot currently be measured.

Flawed targets, flawed framework

The new Closing the Gap framework as outlined in the 2020 Agreement is a complex framework comprising a vast array of intertwining requirements that are not fit for purpose.

Objectives: What does success look like?

The objectives of the previous Closing the Gap framework were set out in the 7 targets, comprising fewer than 100 words. It was very easy to summarise succinctly what success would have looked like: Indigenous adults would be better educated and more of them would be in work. Indigenous children would be going to school every day just like other Australian children and staying in school for longer. And all Indigenous Australians would be living longer.

The objectives of the new Closing the Gap framework are set out in 48 substantive paragraphs (4 priority reform outcomes, 4 priority reform targets, 21 outcomes including socio-economic outcomes and 19 socio-economic targets) comprising over 1,000 words. It is difficult to summarise succinctly what success looks like in this framework.

Measurement: Less is more

In the previous Closing the Gap framework, each target was measured against a set of performance indicators — originally 27 but simplified to 15 performance indicators from 2012. Each performance indicator was reported on through a series of identified statistical data sets overall and disaggregated by different criteria (eg sex, remoteness, age).[48]

The new Closing the Gap framework outlined in the 2020 Agreement has over 150 indicators, each of which is to be disaggregated by further criteria (typically 4, but some as high as 8 or 9) by which achievement of the targets will be measured. It also lists over 140 additional indicators (plus their disaggregation) that are not currently measurable but will be pursued through data development.

Reality bites

In reality the measurement and reporting for the 2020 Agreement does not reflect the aspiration.

Previously, Closing the Gap reporting was done via a Closing the Gap Prime Minister’s Report that included data reporting on the 7 targets via the performance indicators. Now the reporting is done via a Closing the Gap Annual Report produced by the NIAA and a Productivity Commission Annual Data Compilation Report.

The NIAA report is very different from the previous Prime Ministers’ reports. The 17 socio-economic outcomes have replaced the previous 7 targets as the primary benchmark. However, unlike the previous targets, the socio-economic outcomes are qualitative, not quantitative. For example, reporting on the previous target “Close the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians by 2031” has been substituted with reporting on the socio-economic outcome “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people enjoy long and healthy lives”.

Previously, achievement of the targets was measured against the performance indicators. Now, achievement of the socio-economic outcomes is measured against the socio-economic targets and some of the indicators (where possible to measure). However, the data required to measure a number of the socio-economic targets and most of the indicators are unavailable or of poor quality.

The 2023 NIAA report[49] outlined whether each outcome is improving (and whether on track or not) or worsening, referring back to the 2023 Productivity Commission report for details. It then listed government spending initiatives and provided a general summary of ‘Key achievements’ for the year.

The Productivity Commission report does detail statistical data but not as contemplated in the 2020 Agreement. The Productivity Commission report refers to the 2020 Agreement indicators as “supporting indicators”. It reports on those it has data for, but notes that: [50]

“[S]ome supporting indicators lack a clear purpose and this can make them difficult to interpret. Furthermore, several supporting indicators lack data either partly or entirely. This is a particular concern for reporting on socio‑economic outcome area 13 ‘family safety’, with no assessment of progress for the target or data for the supporting indicators. This means at the national level there is no way of knowing through the available data if Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families have been getting safer over the past five years.”

The 2023 Productivity Commission report states there are “significant data and measurement issues” with the new Closing the Gap framework and even that a number of the socio-economic targets are not able to be measured:

“Multiple socio-economic targets cannot be assessed due to a lack of available data. Sometimes data is not available because it is not collected, in other cases it is collected but is of very low quality due to a range of issues (see box A.1), and so is not reported.

As noted in section 3, the data needed for assessing progress is not collected for four targets. For the target 9B ‘community infrastructure’, no data has been collected for the starting point (baseline) or to provide updates on progress. For the other three targets (13 ‘family violence’, 16 ‘strength of languages’ and 17 ‘access to information’) while data for the baseline is available, updates since then are not.

For a further two targets, data is collected but quality issues limit the scope of the assessments of progress. For target 1 ‘life expectancy’ the national target includes data for only four jurisdictions. For target 14 ‘suicide rates’ the national target includes data for only five jurisdictions, and assessments of progress are not currently available by state and territory.

And for all these six targets and multiple others, data is not available for reporting on some of the required disaggregations of the national target indicator, in particular, disability. For example, no disability data is reported for target 10 ‘adult imprisonment’ and target 11 ‘youth detention’, and while some disability data is reported for target 12 ‘children in out-of-home care’ and target 3 ‘preschool enrolment’ they are not a disaggregation of the target indicator itself.”

Targets indirect and potentially competing

Many of the socio-economic targets in the new Closing the Gap framework are indirect; meaning they do not necessarily drive the behaviours required to improve Indigenous lives in practice, and may work against each other. This is so for the targets on incarceration, out-of-home care and family violence, for example. See Case Study.

The 2020 Agreement was intended to systematise the government interventions and add consistency across policies nationwide. However, government programs are still piecemeal actions and sometimes even contradict each other. For example, in a 2024 report, the Productivity Commission pointed out that changes the Queensland government made to the bail laws mean more Indigenous young people will be incarcerated for longer.[51] But given the growing crime problem in Queensland, these changes are not surprising.

A target that would be both direct and also not cut across initiatives to improve law and order, would be a target to reduce the rate of crime committed by Indigenous people rather than reducing the consequences for offenders.

Oversight and assessment

The 2020 Agreement does not contemplate an independent oversight or audit body, with clause 139 outlining that administration and oversight is the responsibility of the Joint Council.[60] However, in practice, the members of the Council and the parties responsible for the fulfilment of the 2020 Agreement are the same people. This constitutes neither effective nor independent oversight. The 2020 Agreement also contains no consequences for the failure to deliver on the targets.

The Productivity Commission has made a commendable effort to depict the advancement of the 2020 Agreement. However, the primary dashboard on its website is marred by question marks, indicating the absence of data (Figure 3). A more granular analysis reveals a blend of education and crime statistics with varied levels of progress. Yet, numerous indicators lack either the current data, the baseline figures, or in some cases, both. This includes the indicators of females experiencing physical harm, and data on households receiving essential services.[61]

Source: Productivity Commission, Online, Last accessed 30 June 2024.

The absence of data significantly hinders accountability and the evaluation of policies designed to support Indigenous people. A lack of baseline data further complicates the setting of policy targets and the monitoring of progress. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has underscored the deficiency in national administrative and survey data.[62] Presently, the Census remains the only dependable source for Indigenous socio-economic indicators. To remedy this data deficit, the Productivity Commission has suggested establishing a Bureau of Indigenous Data. [63]

Transparency

Transparency in the allocation, processes, and outcomes of funding of programs to deliver on the Closing the Gap Agreement remains elusive. For instance, the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) discloses in its annual report the allocation of funds aimed at ‘Closing the Gap’. It states that “$1,540 million out of the total $1,567 million investment” was made, aligned with outcome areas 5, 8, and 15. However, the report stops short of providing detailed achievements, such as the number of employment opportunities created by this substantial funding. This lack of detailed reporting impedes a clear understanding of the impact such investments have on actual outcomes.[64]

The federal budget also has a similar pattern of inadequate transparency regarding results and targets. One example is the Indigenous Youth Education Package in the 2018-19 budget, which included $200 million for scholarships and mentoring.[65] The media statement from the parliament on this program included the following “Targets will be redeveloped in partnership with Indigenous Australians”.[66] Consultation with Indigenous people is beneficial in some policy designs. However, this funding outcome does not have much room for variation or ambiguity and could be set as simply an uptake of scholarship and/or the education program completion rates.

Overall, there is a persistent lack of timely data, well-defined targets and oversight mechanisms. Moreover, no accountability nor consequences for failing to achieve the targets are embedded in the design and implementation of the Indigenous policies. The complexity, bureaucratisation and ability to update and create new targets will provide ample scope for obfuscation and papering over failures.

It shouldn’t be this complicated

Most of the gap would close within less than a generation if every Indigenous child went to school every day, every Indigenous adult was employed in a real job, and the communities in which Indigenous people live were safe and allowed private property ownership. Just those few achievements would result in improvements in all the other areas that are the focus of the 17 new Outcomes and 19 new Targets.

It is a well-known fact that the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians persists. It is also a fact that the previous Closing the Gap targets were not achieved. The new Closing the Gap framework is complex, over-engineered and proving difficult to measure by the criteria the 2020 Agreement has set.

A better approach would be to set simple, measurable goals, focus on achieving them, and then set and move on to the next ones. It is a mistake to focus on targets that are not achievable unless other targets are met. Start with the root causes and build from there.

For example: no education targets will be achieved if Indigenous children do not attend school at least 90% of the time. And school attendance is far worse in remote areas than other areas. So start with the target of the proportion of Indigenous school-aged children attending school 90 per cent of the time in Years 1 to 10 — being the same as non-Indigenous school-aged children in each area by remoteness. This should be measured by full-year, individualised data (not just one semester). Make this the objective every teacher, education department employee, politician etc, is required to achieve and is assessed by.

When that target is achieved, set new targets on educational outcomes; such as numeracy and literacy, Year 12 attainment, tertiary qualifications and so on. But since no child will be numerate or literate or complete Year 12 or be able to undertake tertiary study if they do not attend school 90% of the time, there is no point setting those objectives until school attendance targets are achieved.

Early childhood development is essential. Many Indigenous children start school well behind because they have a poor start in life from 0-5 years old. The previous and new Closing the Gap targets have targets based on enrolment. The target should also be based on attendance. Once that target is achieved, a new target based on the five domains of the Australian Early Development Census can be set.

Accountability is delivered by holding to account the organisations and individuals responsible for policies and programs. It begins with simple targets that direct all activity towards single, consistent goals that do not require an army of bureaucrats to administer.

Conclusion

We cannot achieve change if we use the same inadequate approach and programs that have proven to fail for years.

The gap is driven by divergence in socio-economic indicators, not by race. Financial and economic independence is what Indigenous people need.

The guiding principle should be to harness the free-market ethos, incentivising economic participation. All government activities and policies must nurture both personal and community-level responsibility to achieve prosperity, encouraging and allowing people to build their own future and phasing out reliance on welfare and government programs.

The pathway presented in this paper is free market economy-driven solutions proven to improve the standard of living and economic inclusion of disadvantaged communities. This paper offers policy options that do not segregate and isolate the remote Indigenous communities. Rather it considers struggling remote Indigenous communities as any other socio-economic disadvantaged group, and offers a results-driven accountable approach that will deliver economic inclusion and participation — the cornerstone of a successful free market economy. Coupled with policy accountability, the lack of which has been grossly overlooked, it offers an effective pathway to closing the gap.

Summary of recommendations

The 2023 Voice referendum sent a clear message to governments and to the corporates and the rest of the big end of town who supported it. Australians do not want divisive and ideology-driven solutions or race-based policies.

Politicians should stop listening to the noise of the Indigenous elite in academia, the public service and government funded organisations, who promote them. Politicians should listen to the silence.

And the silence in remote Indigenous communities is deafening. Over 60% of Indigenous voters in remote communities across Australia’s north abstained from voting in the Voice referendum. Over 90% of Aboriginal people in South Australia and Victoria did not turn out to vote for elections for voices in those states.

Australians want real improvements in Indigenous lives and policies directed towards need that deliver outcomes. Especially for Indigenous people in remote Australia, who are the most disadvantaged Australians of all.

Market economy and democracy, the rule of supply and demand as well as the rule of law are the blueprint for economic prosperity and have been proven successful in communities all over the world, regardless of their race, culture or religion. It can work for remote Indigenous communities too.

This paper proposes a roadmap to closing the gap through real economic solutions under four pillars:

- Economic Participation

- Education

- Safe communities

- Accountability.

Economic participation is achieved through business creation and employment.

This languishes in remote Indigenous communities because there is no private, individual property ownership on traditional lands. All land is collectively owned by centralised Indigenous bodies.

And, despite owning vast amounts of land and billions in funds from royalties and other payments for use or loss of land, Indigenous people in these communities live in abject poverty, dependent on centralised, community-controlled organisations for housing and other needs.

This model also exists in towns like Alice Springs with the Aboriginal town camps, which are collectively owned and controlled by Aboriginal controlled ‘councils’ that run some of the most appalling and derelict housing and communities in Australia.

This needs to change.

Collective ownership of townships on traditional lands and town camps needs to be replaced by private, individual property ownership.

And there are already established models of land ownership and land reform that will enable it such as 99 year leasing and strata title.

Education is the key to employment.

There is virtually no employment gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians who have education at the Certificate III or above and none at the highest levels of education. The gap in educational attainment accounts for almost 40 percentage points of the gap in employment.

To get an effective education, a child must attend school 90% of the time. Most Indigenous children in remote communities are not.

Over three quarters of Indigenous children in Very Remote areas and nearly two-thirds of those in Remote areas are not attending school 90% of the time and are not getting an effective education.

We only know this because of a battle waged by the Abbott government and myself as then Chair of the Prime Minister’s Advisory Council to get individualised school attendance data from the states and territories. It was a briefly won battle and the data is no longer published.

State and territory governments’ refusal to be transparent on individualised attendance data reflects their broader lack of accountability for Indigenous people in education and beyond. They are responsible for education and other critical services. But they shirk their responsibilities for their most vulnerable citizens — Indigenous people living in remote communities — and then, when expected to meet their responsibilities, they put their hand out for more federal money. They are let off time and time again.

We need to get all Indigenous children to school, every day and in all of Australia.

The new Closing the Gap framework has targets for Year 12 and tertiary attainment but none for school attendance. They have it around the wrong way.

Start with a target that all Indigenous children attend school 90 per cent of the time. Make this the objective every teacher, education department employee, politician, is required to achieve and is assessed by. When that target is achieved, then set targets on educational outcomes; such as numeracy and literacy, Year 12 attainment, tertiary qualifications and so on. Because no child will be numerate or literate or be able to complete Year 12 or tertiary study unless they attend school 90% of the time.

Safe communities and economic participation are two sides of the same coin.

Alice Springs has been in crisis for over 2 years after alcohol bans and cashless welfare were abolished across the NT. But the underlying cause of this crisis is more fundamental. In every community the world over, social breakdown, violence and drug and alcohol abuse go hand in hand with low school attendance, unemployment and chronic intergenerational welfare dependency.

The only way to lift people out of this is economic participation. But economic participation will not thrive in unsafe communities.

Communities beset by crime, drug and alcohol abuse, violence and other social dysfunction, will have fewer businesses and employment opportunities and more people involved in criminal activity.

Alcohol bans and cashless welfare are an essential start to breaking this cycle; bringing a community back from the brink and breathing space for more permanent change.

Then we need a bridge from dysfunctional behaviour to economic participation. Make employment and education a consequence of crime, essentially sentencing offenders to work or education. Use the powers of courts to impose custodial sentences to impose education and/or training, including in specialised boarding facilities or wilderness programs or work camps. And all of this should apply to everyone – Indigenous and non-Indigenous.

Accountability is essential for the effectiveness of every policy and initiative, however well intentioned.

The new Closing the Gap framework adopted in 2020 falls woefully short on accountability.

It is a complex framework comprising a vast array of intertwining requirements and is not fit for purpose.

The outcomes are qualitative. It is unclear what success looks like.

The targets are flawed. Many are unmeasurable, the data being unavailable or of low quality.

Many are indirect and do not necessarily drive the behaviours required to improve Indigenous lives, and even work against each other. For example the outcomes and targets on Indigenous incarceration, out-of-home care and family violence.

- The only sustainable way to reduce Indigenous incarceration is to reduce the crimes committed by Indigenous people, most being violent crimes against Indigenous victims. This is the underlying cause of imprisonment rates. Yet, nothing addressing commission of crime is listed as an indicator for any of these targets.

- The only sustainable way to reduce Indigenous children in out-of-home care is to reduce violence, sexual abuse and neglect of Indigenous children in their families and communities (and the factors that underpin that behaviour such as alcohol abuse). Yet, nothing addressing these issues is mentioned in the indicators for this target.

- Achieving the target to reduce family violence and abuse against women and children would support achievement of the targets on incarceration and out-of-home care. Yet that target has no available data to measure it and has inadequate baseline data.

Ultimately, there would be improvements in all the stated outcomes on incarceration, out-of-home care and family violence if our recommendations on land reform, school attendance and safe communities were adopted.

* * *

Most of the gap would close within less than a generation if every Indigenous child went to school every day, every Indigenous adult was employed in a real job, and the communities in which Indigenous people live were safe and allowed private property ownership. Just those few achievements would result in improvements across all areas. Race based and ideology-driven policy will not improve Indigenous lives. Australians have sent governments a very clear message that they want a different way.

Appendix 1

Previous Closing the Gap framework – National Indigenous Reform Agreement (2008) [67]

Appendix 2 – Current Closing the Gap framework – National Closing the Gap Agreement (2020)

Endnotes

[1] Note: For the purposes of this paper the term ‘remote’ is used as a collective reference to Remote, Very Remote and regional Indigenous communities, unless otherwise specified.

[2] Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, Worlds Apart: Remote Indigenous disadvantage in the context of wider Australia, CIS Policy Paper 34 (2021)

[3] Nyunggai Warren Mundine “No Vote was deafening but PM still not listening” The Daily Telegraph 20 December 2023. Based on data analysis of 2023 Referendum results published by the Australian Electoral Commission in booths in Halls Creek, Fitzroy Crossing, Yarrabah, NT postcode 0822 and Australian Bureau of Statistics census data in corresponding statistical or local government areas.

[4] Evans, M., Polidano, C., Moschion, J., Langton, M., Storey, M., Jensen, P., & Kurland, S. (2021) Indigenous Businesses Sector Snapshot Study, Insights from I-BLADE 1.0. The University of Melbourne

[5] Evans, M., Polidano, C., Moschion, J., Langton, M., Storey, M., Jensen, P., & Kurland, S. (2021) Indigenous Businesses Sector Snapshot Study, Insights from I-BLADE 1.0. The University of Melbourne

[6] Evans, M., Polidano, C., “The power of the Indigenous business sector” Pursuit, 20 April 2021, Online, Accessed 20 March 2024

[7] Nyunggai Warren Mundine AO (2023), Joining the Real Economy: A quantitative mapping of the economic potential of remote Indigenous communities, Research Report 45, Sydney: The Centre for Independent Studies, March 2023

[8] There are numerous types of Indigenous entities that receive royalty and other payments and hold assets for the benefit of Aboriginal communities and traditional owners, including land trusts and statutory bodies established under Commonwealth, state and territory legislation and Indigenous corporations registered under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders) Act 2006 (Cth) (CATSI). There is no single source of data on total assets and income of the “Indigenous estate”. However, by way of illustration:

- The Aboriginals Benefit Account is a special account legislated under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 that receives and distributed monies generated on Aboriginal land in the NT and calculated referable to statutory royalty payments. In FY2021-2022, the ABA received royalties of $350 million and had net assets of $1.4 billion as at 30 June 2022. In FY2022-2023, the ABA received $379 million in royalties and had net assets of $0.9 billion as at 30 June 2023, with the reduction being due to a $500 million provision to cover the establishment and operation of the Northern Territory Aboriginal Investment Corporation during that financial year. Most assets comprise cash and term deposits of 6 months to 5 years. (National Indigenous Australians Agency Annual Report 2022-2023 Section 5 and Appendix E).

- In 2014–15, the top 500 Indigenous corporations registered under CATSI had a combined income of $1.88 billion and assets of $2.22 billion. 43 per cent of the top 20 Indigenous corporations’ income was self-generated and 17.7 per cent was from other sources including mining royalties, native title compensation and philanthropic gifts. ( ANAO Report No.3 2017–18 Performance Audit. Supporting Good Governance in Indigenous Corporations p 17).

- The Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation (a Corporate Commonwealth entity established under legislation) reported for FY 2023 total net assets of $408 million (including $118 million in financial assets) and total own source net income of $190 million. (Annual Report 2022-23 Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation)

- The NSW Aboriginal Land Council had net current assets of over $600 million as at 30 June 2023 and generated just over $30 million in revenue for FY2022-2023 from investment and other revenue (excluding grants, contributions and other payments from governments). (2022-2023 NSW Aboriginal Land Council Annual Report).

- There are numerous land trusts and organisations receiving and holding royalties and other income generated from traditional lands and holding substantial funds. For example, the Western Cape Communities Trust is set up to pay for health, education and essential infrastructure for the Aboriginal community of Aurukun with a population of around 1000 people. In FY 2021-2022 WCCT received revenue from royalties and investment income of approximately $30 million, with a profit of $18 million and had net assets of $154 million (including net current assets of $54 million) as at 30 June 2022.

[9] Qian, J., Riseley, E., & Barraket, J. (2019). Do employment-focused social enterprises provide a pathway out of disadvantage? An evidence review. Australia: The Centre for Social Impact Swinburne

[10] Productivity Commission, Closing the Gap Information Repository, Accesses 19 March, Available https://www.pc.gov.au/closing-the-gap-data/dashboard/se/outcome-area8

[11] AIHW 2021, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-employment

[12] Qian, Joanne; Riseley, Emma and Barraket, Jo. (2019). Do employment-focused social enterprises provide a pathway out of disadvantage? An evidence review. Australia: The Centre for Social Impact Swinburne.

[13]AIHW NIAA Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/2-08-income

[14]AIHW NIAA Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/2-08-income

[15] AIFS (2022) https://aifs.gov.au/resources/short-articles/supporting-young-people-experiencing-disadvantage-secure-work

[16] Lamb, S., Huo, S., Walstab, A., Wade, A., Maire, Q., Doecke, E., … & Endekov, Z. (2020). Educational opportunity in Australia 2020: Who succeeds and who misses out.

[17] Productivity Commission (2024) Dashboard https://www.pc.gov.au/closing-the-gap-data/dashboard

Accessed 1 April 2024.

[18] The Forrest Review: Creating Parity, Commonwealth of Australia 2014

[19] AIHW (2023) https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-employment

[20] ACARA (2023) National Report on Schooling in Australia Data Portal: Student attendance- external site opens in new window, Sydney, ACARA, accessed 30 March 2023.

[21] The Forrest Review: Creating Parity, Commonwealth of Australia 2014

[22] Nyunggai Warren Mundine, Warren Mundine in Black and White: Race, Politics and Changing Australia, Pantera Press, 2017;

[23] Nyunggai Warren Mundine, Warren Mundine in Black and White: Race, Politics and Changing Australia, Pantera Press, 2017; Nyunggai Warren Mundine “Closing the Gap: improvements in living standards take root through steady school attendance”, The Australian 17 February 2018

[24] Closing the Gap: Prime Minister’s Report 2016, p17

[25] National Agreement on Closing the Gap https://www.closingthegap.gov.au/national-agreement Accessed 15 April 2024.

[26] AIHW NIAA https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/2-05-education-outcomes-young-people#keymessages, Accessed 31 March, 2024

[27] The Forrest Review: Creating Parity, Commonwealth of Australia 2014

[28] Morrissey, T. W., Hutchison, L., & Winsler, A. (2014). Family income, school attendance, and academic achievement in elementary school. Developmental psychology, 50(3), 741.

[29] Ou, S. R., & Reynolds, A. J. (2008). Predictors of educational attainment in the Chicago Longitudinal Study. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(2), 199.

[30] Klein, M., Sosu, E. M., & Dare, S. (2020). Mapping inequalities in school attendance: The relationship between dimensions of socioeconomic status and forms of school absence. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105432.

[31] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-02-27/nt-teachers-to-strike-added-pressure-truancy-officers/5287756

[32] https://www.skynews.com.au/australia-news/politics/natasha-fyles-calls-for-more-funding-in-alice-springs-with-no-timeframe-for-public-release-of-crime-and-alcohol-report/news-story/298c45f3a4c0d4cd90c5f66f73038db5 [Accessed 6 July 2024]

[33] The Australian, “Scandal of underspending on territory’s remote communities” by Nicholas Rothwell 8 August 2015. Available here: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/inquirer/scandal-of-underspending-on-territorys-remote-communities/news-story/12e268cd80bdde6bc406b82f684dacfc [Accessed 6 July 2024]

[34] Yothu Yindi Foundation submission to the Productivity Commission’s Inquiry into Horizontal Fiscal Equalisation, 10 November 2017. Available here: https://yyf.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/YYF-PRODUCTIVITY-COMMISSION-ENQUIRY-HFE-10-NOV-2017.pdf [Accessed 6 July 2024]

[35] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-10-02/remote-nt-schools-underfunded-freedom-of-information-report/102913424 [Accessed 6 July 2024]

[36] https://www.pm.gov.au/media/australian-and-northern-territory-governments-agree-fully-and-fairly-fund-all-nt-public

[37] ABS (2012) https://abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/IREG708

[38] AIHW 2023 https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-community-safety

[39] M. Cunningham (2024, January 13) Alice Springs faces a ‘crisis of confidence’ as town’s crime issues shift towards property crime and grog continues to flow: ‘I’ve never seen it like this’

[40] Motta, V. (2017). The impact of crime on the performance of small and medium-sized enterprises: Evidence from the service and hospitality sectors in Latin America. Tourism Economics, 23(5), 993-1010.

[41] Mahofa, G., Sundaram, A., & Edwards, L. (2016). Impact of crime on firm entry: Evidence from South Africa. Economic Research South Africa (ERSA) Working Paper, 652.

[42] Hao Fe & Viviane Sanfelice, How bad is crime for business? Evidence from consumer behavior, Journal of Urban Economics, Volume 129, May 2022

J.R. Hipp, S.A. Williams, Y.-A. Kim, J.H. Kim, Fight or flight? Crime as a driving force in business failure and business mobility, Social Science Research

Volume 82, August 2019

[43] Lorde, Troy, and Mahalia Jackman. “Evaluating the impact of crime on tourism in Barbados: A transfer function approach.” Tourism Analysis 18.2 (2013): 183-191; Mataković, Hrvoje, and Ivana Cunjak Mataković. “The impact of crime on security in tourism.” Security and Defence Quarterly 27.5 (2019): 1-20; Tevdoradze, Sopiko, Zurab Mushkudiani, and Nugzar Tevdoradze, “The effect of criminal activity on tourism”, The New Economist 19.1 (2024): 25-2; Motta, V. (2017). The impact of crime on the performance of small and medium-sized enterprises: Evidence from the service and hospitality sectors in Latin America. Tourism Economics, 23(5), 993-1010.

[44] ACARA (2023) National Report on Schooling in Australia Data Portal: Student attendance- external site opens in new window, Sydney, ACARA, accessed 30 March 2024.

[45] AIHW (2024) “Youth justice” https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/youth-justice, accessed 1 April 2024.

[46] Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, Worlds Apart: Remote Indigenous disadvantage in the context of wider Australia, CIS Policy Paper 34 (2021)

[47] Nyunggai Warren Mundine, Warren Mundine in Black and White: Race, Politics and Changing Australia, Pantera Press, 2017; Nyunggai Warren Mundine “Closing the Gap: improvements in living standards take root through steady school attendance”, The Australian 17 February 2018

[48] The data sets for each year can be found on the Productivity Commission website. https://www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/national-agreements/indigenous-reform

[49] Closing the Gap Commonwealth 2023 Annual Report & 2024 Implementation Plan. Available here: https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2024-02/ctg-annual-report-and-implementation-plan.pdf [Accessed on 30 June 2024]

[50]Closing the Gap Annual Data Compilation Report July 2023 Available here: https://www.pc.gov.au/closing-the-gap-data/annual-data-report/report [Accessed on 30 June 2024]

[51] Productivity Commission (2024), “Review of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap”, Study report, volume 1, Chapter 8, Canberra.

[52] Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, Worlds Apart: Remote Indigenous disadvantage in the context of wider Australia, CIS Policy Paper 34 (2021)

[53] The Australian, 6 March 2018, ‘Removed indigenous kids ‘exposed to further abuse’ by Victoria Laurie. Available from https://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/indigenous/removed-indigenous-kids-exposed-to-further-abuse/news-story/136acabddf32f288fe3efdb29030a765 [Accessed on 30 June 2024]; Jeremy Sammut, Indigenous child protection regime ‘apartheid’, 9 March 2018 published by CIS. [Accessed on 30 June 2024]

[54] https://www.pc.gov.au/closing-the-gap-data/dashboard/se/outcome-area13#:~:text=Nationally%20in%202018%2D19%2C%208.4,1). [Accessed 1 July 2024]

[55] Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, Australia, 2018-19, Cat. no. 4715.0. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/national-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-health-survey/latest-release#physical-harm [Accessed 1 July 2024]

[56] https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/mf/4714.0 [Accessed on 1 July 2024]

[57] Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, Homeland Truths: The Unspoken Epidemic of Violence in Indigenous Communities, CIS Occasional Paper 148 (2016)

[58] Justice Judith Kelly, Address to 2022 Women Lawyers’ Drinks, 26 August 2022. Available here: https://supremecourt.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/1132015/2022-Women-Lawyers-drinks.pdf [Accessed 6 July 2024]

[59] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-05-03/jacinta-nampijinpa-price-voice-referendum-no-campaign-reflection/103779330;

‘Anti-racism’ makes it impossible to speak up about Aborginal domestic violence

[60] Australian Government. “National agreement on closing the gap. Canberra: National Indigenous Australian Agency”; 2020 [Accessed 21 March 2024]. Available from: www.closingthegap.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/national-agreement-ctg.pdf

[61] Productivity Commission, Closing the Gap Information Repository, Accesses 1 April 2024, Available https://www.pc.gov.au/closing-the-gap-data/dashboard

[62] RBA (2022) “First Nations Businesses: Progress, Challenges and Opportunities”,

https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2022/jun/first-nations-businesses-progress-challenges-and-opportunities.html

[63] Productivity Commission (2024) Review of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap, Study report, volume 1, Chapter 7, Canberra.

[64] Commonwealth of Australia, National Indigenous Australians Agency, Annual Report 2022–23

[65] https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/BudgetReview201920/IndigenousAffairs

[66] https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query%3DId%3A%22media%2Fpressrel%2F6497231%22

[lxvii] For the original 6 targets: National Indigenous Reform Agreement (Closing the Gap) 2008. https://webarchive.nla.gov.au/awa/20121107000244/http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/144916/20140815-0758/www.federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/content/npa/health_indigenous/indigenous-reform/national-agreement_sept_12.pdf [Accessed on 17 April 2024]. However, changes were made before implementation and again in 2012. A record of the original targets and performance indicators and those applying each year from 2009 to 2019 can be found in the annual National Agreement Performance Information reports by the Productivity Commission which can be found here: https://www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/national-agreements/indigenous-reform. [Accessed on 30 June 2024]. For the 7th school attendance target: Prime Minister’s Closing the Gap Reports 2015 & 2016.

[lxviii] Original Targets are shown plus the substantive change to Early Childhood Education and the new School Attendance Target. The wording of the other Targets was modified slightly from 2016. The exact wording of the Targets as at 2019 is set out in Table 1.